Chartbook #43: An IMF-Crisis Made in America

Kristalina Georgieva and the politics of the World Bank's Doing Business Indicator

Will the Managing Director of the IMF survive the day?

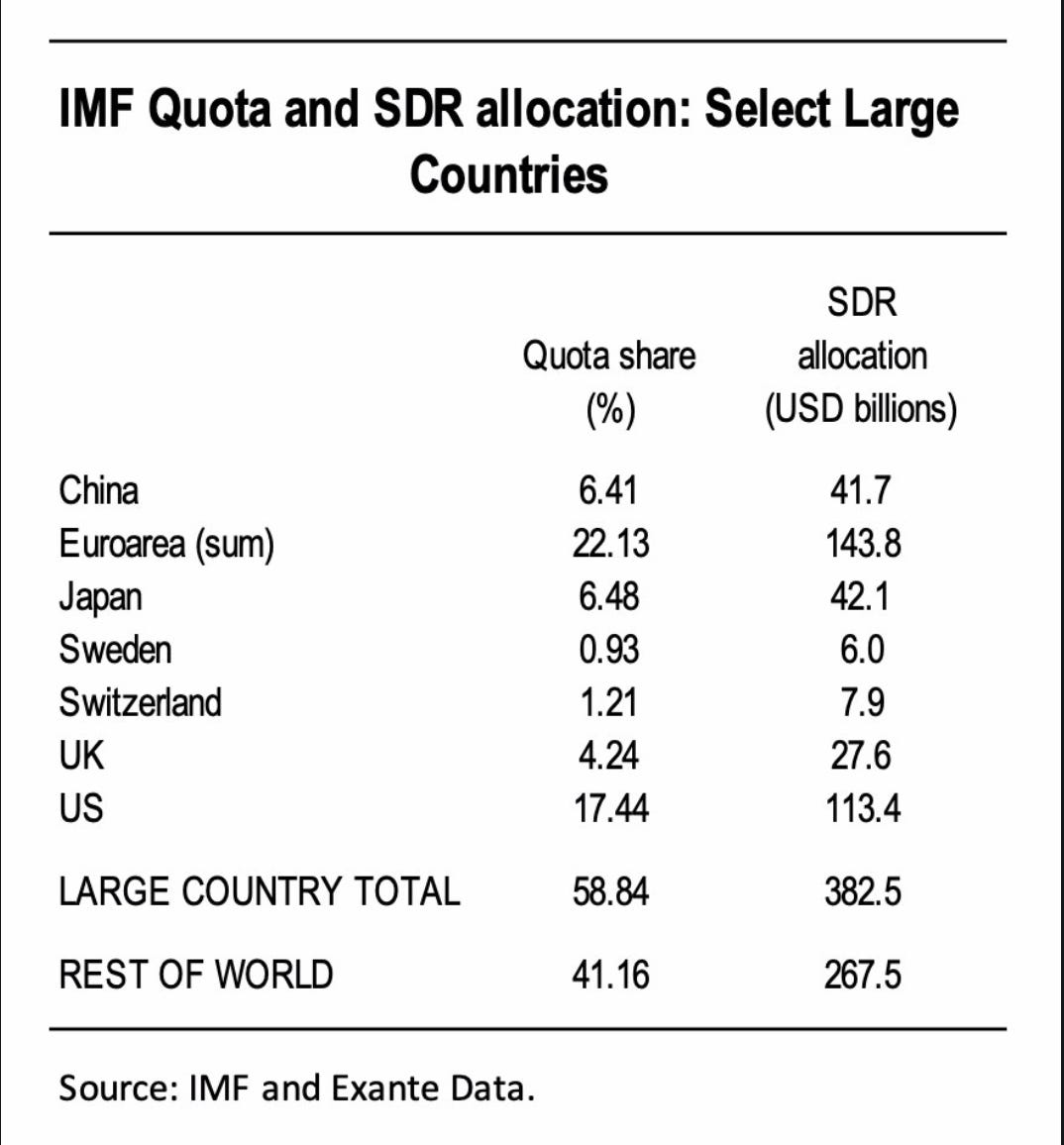

This is not the normal question with which to begin the “fall meetings” of the Bretton Woods Institutions - IMF and World Bank. The annual meetings are the big global jamboree for policy wonks and policy-makers. Since 2009 they have come to be tied to meetings of the G20. Unlike the UN General Assembly, in which every country has one vote, or the Security Council, which reflects the global power structure at the end of World War II, the IMF/World Bank/G20 meetings are the world assembled according to the balance of economic power.

This is how that weighting looks right now.

Source: General Theorist

This year, the world economic powers have to start their deliberations by deciding whether Kristalina Georgieva, formerly the #2 at the World Bank and now the #1 at the IMF can stay in her post. And if not, what implications that has for the position of David Malpass at the World Bank.

The scandal, if that is the right name for what is happening, involves a report commissioned by the current leadership of the World Bank into activities involving the compilation of the World Bank’s Doing Business index in 2017.

The Doing Business Index was the most widely watched ranking issued by the World Bank. This may seem surprising, but as Dan Drezner explains in this smart column a wide range of political science research shows that governments actually care about these rankings.

It should also be said, however, that in the bestiary of economic numbers the World Bank’s Doing Business index was one of the most synthetic. All economic numbers are cocktails of concepts, institutional definitions, politics and quantifying enumeration. But the Doing Business index is a truly synthetic score - like a college ranking or a quarterback rating. The idea in this case was to measure how easy it is to invest or start a business.

The ranking seeks to summarize the fact that “an entrepreneur in a low-income economy typically spends around 50 percent of the country’s per-capita income to launch a company, compared with just 4.2 percent for an entrepreneur in a high income economy. It takes nearly six times as long on average to start a business in the economies ranked in the bottom 50 as in the top 20.”

Such differences are no doubt real. The question is how to measure them and to reduce them to a single index. In the eyes of its many critics, what the World Bank numbers actually amounted to was something more like a beauty contest, with countries judged on the degree to which they conformed to a script of Washington consensus-approved “reforms”, as judged by a handpicked group of local experts and by the World Bank analysts who “owned” the index. Tellingly, it took concerted pressure from the Obama administration, itself under pressure from US Labour Unions, to have an index component removed that rewarded countries for loosening protective labour legislation.

The numbers were, in short, Washington consensus orthodoxy, recast in statistical form. Simeon Djankov, the World Bank economist who presided over the index - rather high-handedly if one believes the reports - was a Bulgarian veteran of the transition debates of the 1990s. As Djankov has explained, the index was designed to reflect ideas about the role of institutions in promoting economic growth put forward by so-called “transitologists” and the campaigning neoliberalism of the Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto. In particular, Djankov collaborated with Andrei Shleifer, one of the most controversial of the carpetbagging economists of the 1990s.

Independently of the scandal now engulfing it, an expert panel had subjected the index to withering criticism.

But, if the statistics were murky, so too were the politics that have triggered today’s scandal.

The critical investigation into the goings-on in 2017 was launched in 2020-2021, as a retrospective exercise. The current leadership of the World Bank was put in place by Donald Trump in 2019. The report concentrates on the activities of Georgieva, now at the IMF, under the World Bank Presidency of Jim Kim, nominated by Obama in March 2012.

The allegation is that in 2017 Kim and Georgieva exercised undue pressure on World Bank staff to produce a more favorable result for China in the influential annual ranking exercise.

The investigative report produced by the influential law firm WilmerHale on the basis of extensive interviews with World Bank staff, paints a vivid picture, of feverish bureaucratic politicking.

78 Was the ranking of China in the World Bank's Doing Business index in 2017. In the summer of 2017 it became clear that China would rank lower in the next issue of the report, due for publication in October. This was not because China was backsliding but because others had upped their “reform” efforts. Existing procedures suggested that China would drop to rank 85. The WilmerHale report paints a vivid picture of the frantic effort to redress that result. It culminates over the weekend of 28-29 October with Georgieva meeting a “Doing Business manager” in the driveway of their home, to personally collect a copy of the final report, which safely restored China to 78th place in the global rankings.

The report is masterfully put together, both damning and yet careful in avoiding direct allegations of impropriety. The picture painted is somewhere between All the President’s Men and In the Thick of It.

Georgieva denies any wrong-doing. Senior members of the World Bank staff who were directly involved in compiling the index, exonerate Georgieva and insist that the WilmerHale report is slanted and took their testimony out of context.

In any case, the damage is done. The US Congress is in uproar. Georgieva’s alleged favoritism towards China will be red meat for the likes of Ted Cruz. As Ed Luce has argued, if she stays on, with her legitimacy weakened, the IMF is much enfeebled.

If, on the other hand, Georgieva is forced to resign, it would be a shock to the European countries that nominated her, as well as the many other countries in the developing world that have backed her as Managing Director and strongly approve of the direction she is taking the IMF in.

During her tenure so far, Georgieva, has been vocal in demanding a more proactive role for the Fund in addressing humanitarian crises and the climate emergency.

This Lunch with the FT profile by Brendan Greeley is intriguing.

”Kristalina Georgieva starts to sing, in Bulgarian, right there at the table — quietly, but firmly, the way you might sing to a child on absolutely her last lullaby of the evening. It is a song she wrote as a teenager in the late 1960s, in her grandparents’ village in the mountains in communist-era Bulgaria, when she ran out of shelves in the local library and started reading philosophy. She finishes a couplet, then translates.

But what is the value of Kant and Spinoza

If somebody else writes predictions for me?“

Ousting Gergieva, would be more than merely a personnel decision. It would be hard not to see it as a victory for the conservative wing of international finance.

*******

This crisis, spun out of allegations about events in 2017, has a strange timewarp quality about it.

It revolves, inevitably, around the rise of China, its influence at international organizations and differences between Americans and Europeans. It feels very 2020/2021. But what is actually at stake, is the degree to which China in 2017 was conforming to the World Bank’s standards of reform and market openness. The allegation is that Kim and Georgieva intervened because they feared that Beijing would be upset by a low score.

It is as if the old narrative of Chinese convergence (on standards set by the Washington consensus), has crashed into the new narrative of great power competition between China and the US. Either way, China cannot win. Or rather, either way, one or other group of Americans are angry.

So, the end of the Cold War and the rise of China are in the background here, but, the crucial point to insist upon, is that this is a crisis made in America.

The incident in 2017 and its subsequent investigation reflect the turmoil of the transition from the Obama to the Trump and the Biden Presidencies. The latest report was triggered in Washington DC, by office politics within the World Bank and IMF headquarters. The investigative reports were unleashed on the world by David Malpass, a notorious enemy of China’s rise, appointed to the World Bank Presidency by Trump. The Biden Presidency will have a key role in deciding the outcome. A critical factor in their decision-making will be the attitude of the US Congress.

******

American power is as visible in the silences in proceedings, as it is in the public criticism and denunciation. The report by WilmerHale frames its graphic account of the making of the index in September and October 2017 against a dramatic backdrop.

Kim and Georgieva were struggling to hold China on side because they feared that “one key stakeholder would meaningfully reduce its commitment to the institution”, as WilmerHale puts it. Georgieva told investigators that she feared that nothing less than the survival of multilateralism was at stake.

WilmerHale never tells us who the “key stakeholder” was that was causing such stress and making the World Bank’s situation so precarious. It was clearly not China. Beijing actively backed a capital raise. It was, the United States under Donald Trump.

In other words the WilmerHale report alleging favoritism towards China simply omits the context which put the World Bank leadership under such pressure.

In 2017 Trump opened his broadside against global institutions, like UNESCO and the WTO. The World Bank was in the crosshairs because it lends on a large scale to middle-income countries including China. Kim and Georgieva were not just trying to placate Beijing. They had to deal with the White House too. And whereas their concerns for China’s ranking were a matter for technical discussions behind closed doors, their efforts to ingratiate the World Bank with the Trump administration were embarrassingly public.

In the spring of 2017, the World Bank offered to put its infrastructure expertise at the disposal of the White House for its much ballyhooed infrastructure plan. Even more overtly it provided administrative support for Ivanka Trump’s pet project, a $200 million fund for women’s entrepreneurship with half the funding provided by the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

As the Financial Times remarked in May 2017:

“Mr Trump’s fondness for mixing public policy with personal considerations is not the least of his many flaws. But for the (World) bank, securing continuing funding from the US is not worth the blow to its credibility that such a quid pro quo would deliver. …. Mr Kim is in a difficult position. The World Bank does not normally have to deal with a White House that seems so indifferent to its continued existence. But risking the bank’s credibility by appearing to engage in personal favours for the US president is not the way to proceed.”

Not a word of any of this in the WilmerHale report. The report narrows to a police procedural what was, in fact, a geopolitical balancing act.

Nor should this be surprising. As Mark Copelovitch remarks, it is not as though politicking is not part of what the World Bank and the IMF do and that extends to the politics of statistics.

The tuning of the numbers may leave a bitter taste in the mouth, but there is no innocence in this business. Rather than denouncing their balancing act, it would be fairer to judge Kim and Georgieva by the outcome they achieved. For a fairly modest price, they held China onside and in the end persuaded the Trump administration to back a capital raise.

By 2018, it seemed perhaps as though Kim and Georgieva had navigated the rapids. They had, in Bruno Latour’s terms, withstood a trial of strength and when things hold together, “they start becoming true”.

But, the problem with the balancing act of modern global politics is that the trials of strength never ends. The forces at play are constantly shifting and so too is the narrative.

**********

The Doing Business index itself was a running sore. It was a rickety and unpredictable construction shot through with discretion and complex judgements.

In January 2018, shortly after the China incident, Nobel laureate Paul Romer resigned as chief economist of the World Bank, after calling into question the way in which Chile, under the social democratic government of Michelle Bachelet, had been repeatedly downgraded in the Doing Business rankings. He suspected foul play on the part of the staff involved with the index at the World Bank. At the time, none other than Georgieva took to the pages of the Wall Street Journal to defend the integrity of the index. And before resigning, Romer backed away from some of his criticisms.

At that point the front was still intact. But then, in January 2019, rather than hunkering down and outlasting the Trump presidency, Jim Kim resigned from the World Bank to join a private infrastructure firm. That enabled Trump to appoint David Malpass, one of the loudest critics of the Bank and its alleged pro-China bias, to the top job, leaving Georgieva in an uncomfortable position. When Christine Lagarde, then boss of the IMF, emerged as the replacement for Mario Draghi at the ECB, Georgieva jumped at the chance to succeed Lagarde at the IMF.

Malpass and Georgieva cooperated tolerably well in 2020, but the skeletons were in the closets and all it took was a whistle-blower at the World Bank to give Malpass his opportunity to settle some old scores. As one of the chief instigators of the Trump administration’s bullying of the World Bank in 2017 - the attack that had put Kim and Georgieva under such intense pressure - Malpass has now invited the world to see how the sausage was made.

*********

The operation has added piquancy because Malpass has his own problems with the index.

China isn’t the only major player. There are also the Gulf states to consider.

As Justin Sandefur of CGD makes clear in a powerful post. The WilmerHale report is remarkably taciturn when it comes to the spectacle of “Davos in the Desert” in 2019, the Saudi business summit hosted by MBS and attended by Jared Kushner, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin and David Malpass of the World Bank.

As Sandefur sums it up:

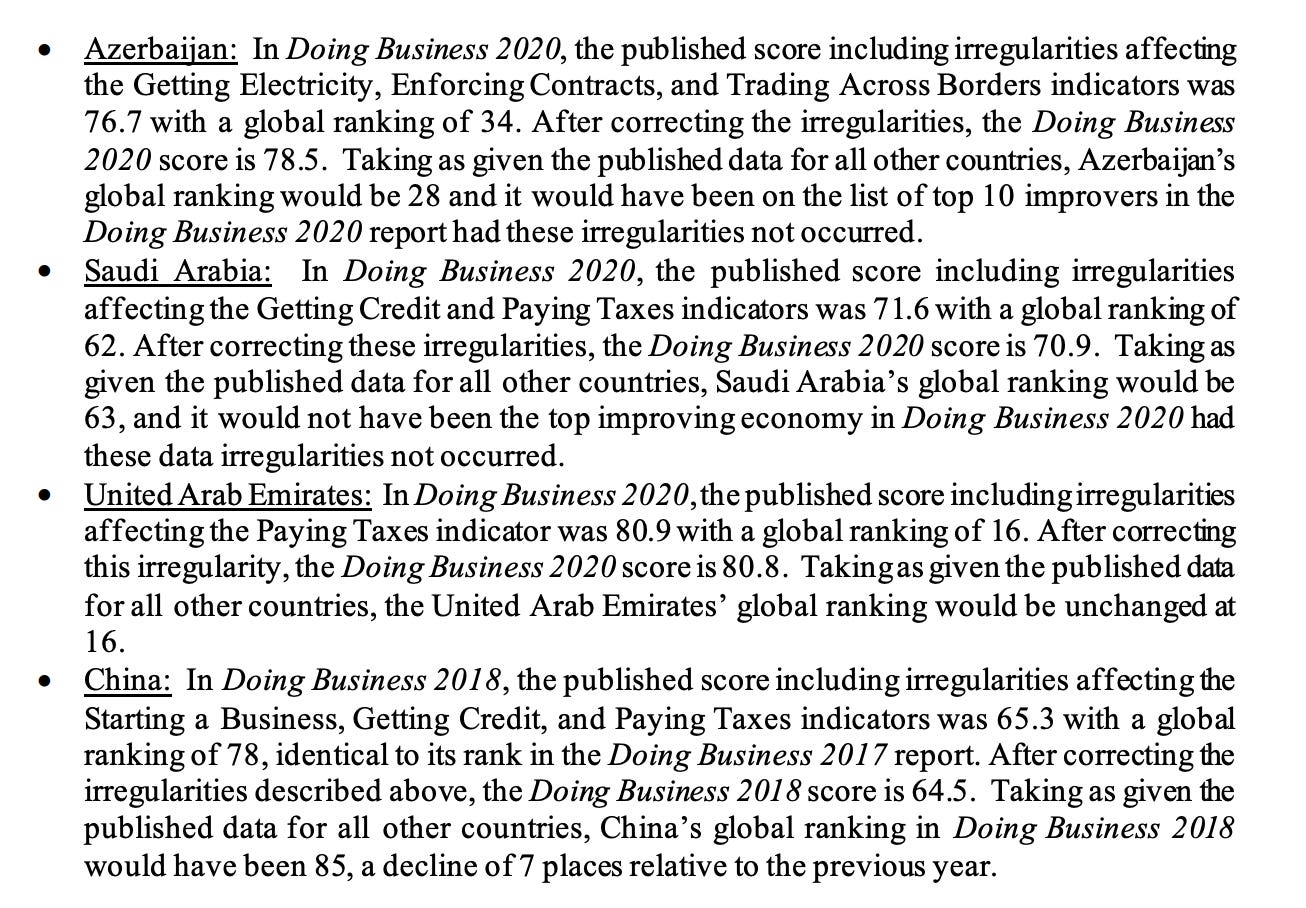

“On the eve of the Riyadh event, the World Bank launched the 2020 Doing Business rankings, and declared with much fanfare that the top reformer in the world was none other than Saudi Arabia.

The only problem was that the data had been manipulated (again).

The WilmerHale report notes that the original calculation had Jordan coming out as the top reformer, but Simeon Djankov—the Doing Business founder who was also at the center of the China scandal—ordered the team to find a way to alter the data to knock Jordan out of the top place, and to add points to Saudi Arabia’s score. The method used to help Saudi Arabia inadvertently helped the UAE as well, but didn’t affect its overall ranking.”

The motive for this change, and even who ordered it, is contested among the individuals interviewed. But the WilmerHale report does note that “we identified no evidence suggesting that the Office of the President or any members of the Board were involved in the data changes affecting Saudi Arabia and UAE in the 2020 report.”

The Sandefur post is really excellent. Highly recommended.

Nor was Saudi Arabia the end of Malpass’s problems with the Doing Business index. As investigative reporting by Bloomberg has unearthed, after hailing Saudi Arabia as top reformer in 2019, in the summer of 2020 Malpass faced a set of data which showed China soaring up the league table from 31 to 25th place. Whatever may be said for the adjustments in 2017, they would seem to have been generally in the right direction!

Such a high ranking was clearly not to Malpass’s liking, and it would have sat even worse with his sponsors in the Trump administration. After discussing various technical changes that might have reduced China’s score, the decision was taken to announce that in light of “data irregularities” the publication of the entire report would be suspend.

An internal December 2020 Management Report to the World Bank confirmed not one but four instances of “data irregularities” that put in question the integrity of the entire system.

Source: World Bank

********

So, the world is confronted in October 2021 with a toxic hangover of the Washington consensus. A battle over a tendentious index that no longer exists, unleashed by a World Bank management team installed by Trump, at odds over China with their predecessors. Which begs a question, if this crisis is brewed in Washington, where does the Biden administration stand?

What about the US Treasury? Clearly it cannot act too publicly. Congress is a minefield. But why is Yellen not answering Georgieva’s calls? And why does the press know? Who is handling international affairs at Treasury?

When Georgevia arrived at the IMF, the number #2 was David Lipton, a heavy hitter appointed by Obama. Rather than allowing Lipton to finish out his term and drawing on his expertise, Georgieva pushed him out. Instead, she accepted the appointment by the Trump administration of a replacement for Lipton who has been politely described as inexperienced and under-qualified, and less politely as a “pot plant”.

Lipton’s ouster has been widely interpreted as a power move. It was widely regretted at the time.

On 2 February 2021 Lipton resurfaced now as counsellor to Janet Yellen at the Treasury. Lipton’s precise role is somewhat ill-defined and significantly underreported, but it appears to involve handling relations with the G7 and the G20, the key stakeholders in the IMF and the World Bank. What he is reported as doing in September is attending meetings at which the Chinese authorities and American financiers discuss regulatory issues and Evergrande. What he is not reported as doing is running interference for the IMF.

Georgieva, one might conclude, does not have many friends in Washington.

It seems more than unlikely, however, that Lipton is part of any “coup” against the head of the IMF. Lipton, committed as he is to multilateral institutionalism, has better things to be doing that knifing Georgieva. Indeed, it is hard to imagine that anyone in the Biden administration welcomes the current mess. Not only is it embarrassing. But it exposes the vacuum where a concerted foreign economic policy on the part of the Biden administration ought to be. Admittedly, Janet Yellen has successfully cooperated with the Europeans on a global tax plan. But beyond that, the Biden administration is struggling to formulate a trade policy towards China that goes beyond platitudes. The Build Back Better World scheme announced at the G7 in Cornwall over the summer is, so far, an empty shell. Lipton is in the role that he is, because there is no Under Secretary of the Treasury for International Affairs in place. The Yellen Treasury has a huge backlog of vacant positions to fill. Having failed to stop the Nord Stream in Germany, the Republican hawks are sanctioning the US Treasury instead.

America’s mess lands in the world’s lap. And above all in the lap of the Europeans. They still regard the IMF as their job. If Georgieva is to go, who is up next? In an alarming thread on twitter, “General Theorist” warns that the Europeans might go back to their shortlist of 2019 and might bump Jeroen Dijsselbloem into the job. That would likely betoken a return to conservative orthodoxy at the Fund.

At the very least Sandefur rightly argues, if Georgieva goes then Malpass should go too.

Make of it what you will, but I’ve just been informed that an event we were due to host at Columbia with France’s Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire on Friday October 15 has had to be canceled. He was expecting to be on his way back to Europe by then. Now Europe’s Finance Ministers have been called for an unscheduled meeting in Washington that day. In 2019 it was Bruno Le Maire who managed the shortlist of candidates to succeed Lagarde.

If you enjoyed this installment of Chartbook, why not considering subscribing.

Or recommend Chartbook to a friend.

Great skullduggery.

Note: i think you meant "less than unlikely" not "more than unlikely".....but the first phrase does sound odd compared to the idiom......