Chartbook 423 Some topical material on Venezuela. Hopefully useful.

It’s been a busy weekend which put me in mind of a classic quip:

Source: Quote Investigator

A lot of us have been learning a lot about Venezuela!

For my part I’m earnestly trying to finish a book (not about Venezuela) so I have been following what is going on out of the corner of my eye. Even so, I can’t help being struck by the frequent mixing together of interesting data with tendentious interpretive claims.

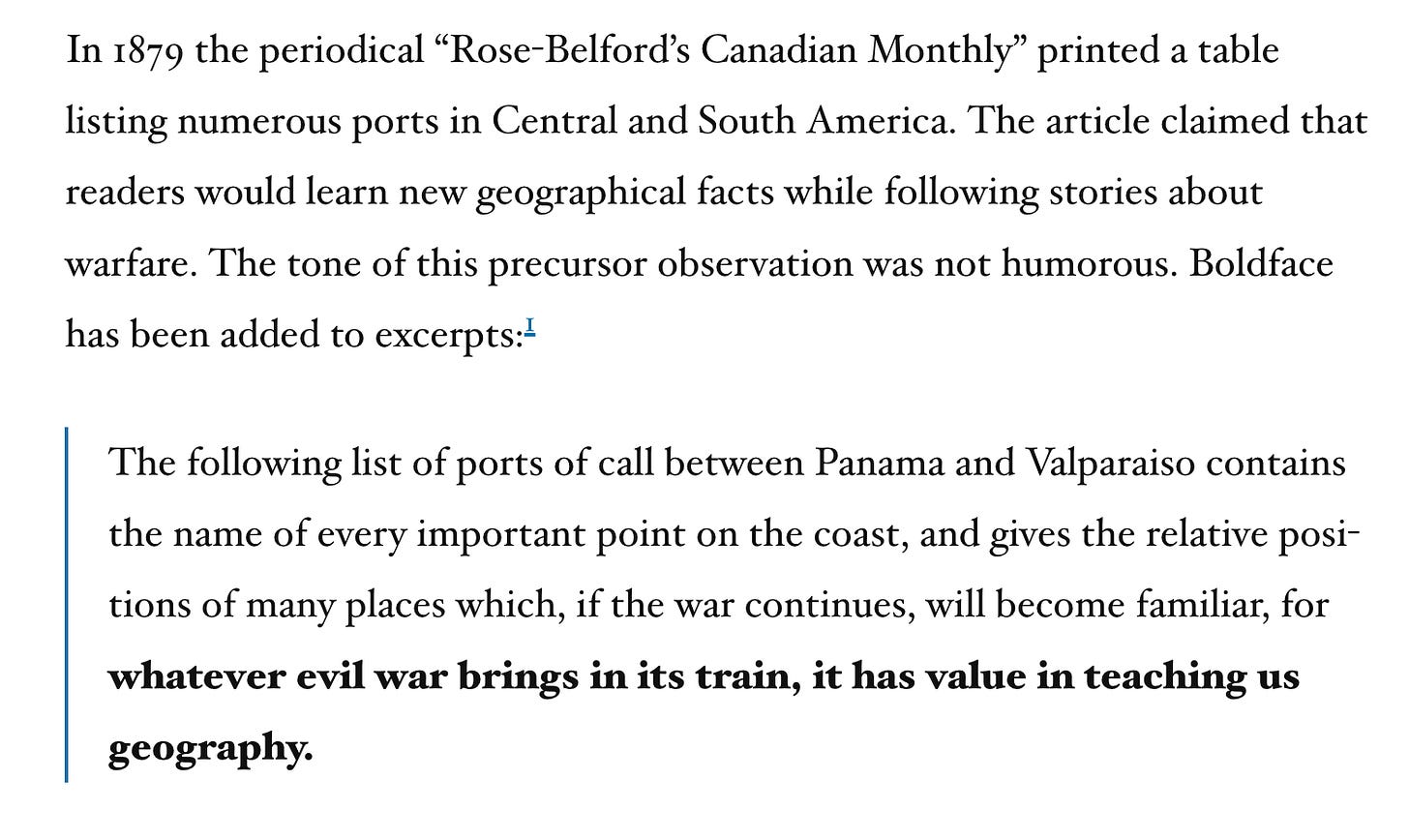

For instance: Historical data on oil rents paid by Venezuela under the pre-OPEC oil regime are very interesting. But what conclusions can you possibly draw? I was sorry to see Gabriel Zucman posting in this fashion.

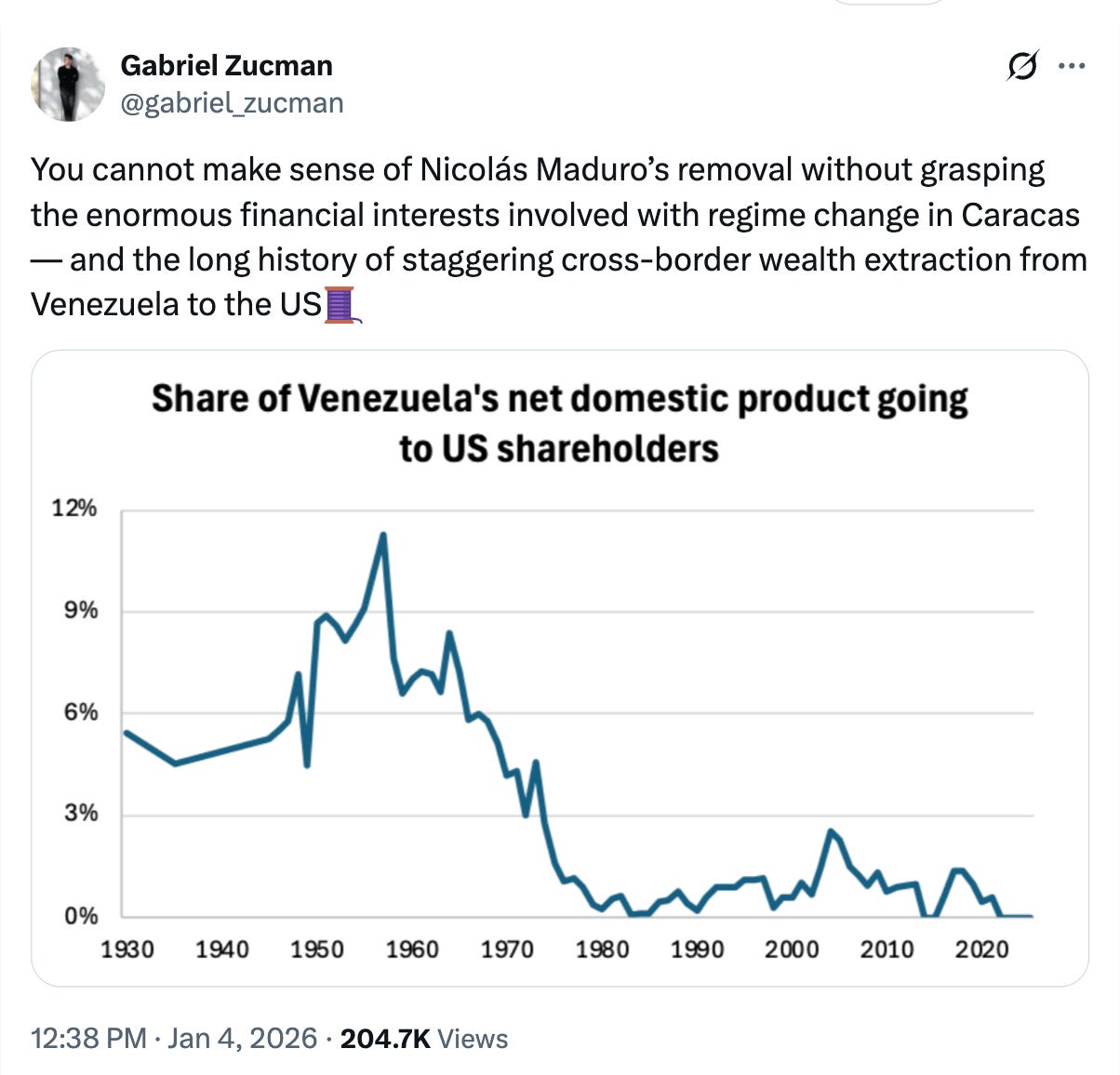

Even as far as Venezuela’s own situation is concerned, to evaluate claims about the relative merits of extractive regimes, one clearly wants an “extraction-adjusted GDP per capita” to get the full picture. And lo and behold, Twitter provides. And yes I am aware that every twitter account comes with its own politics. But this graph is excellent. Clearly, a high rent extraction regime was compatible, to say the least, with rapid economic development in Venezuela. (NOT saying anything about distributional issues, economic diversification etc etc).

BTW Venezuela back in 1960 was a founding member of OPEC along with the Gulf producers.

Oil nationalization in 1976 slashed foreign rents but that was also the moment at which economic growth in Venezuela broadly speaking came to an end. I’m not making any direct causal links. Just trying to get the chronology straight. Nationalization in 1976 seems to have gone relatively smoothly. So much so that the lack of drama disappointed more hard-core resource nationalists.

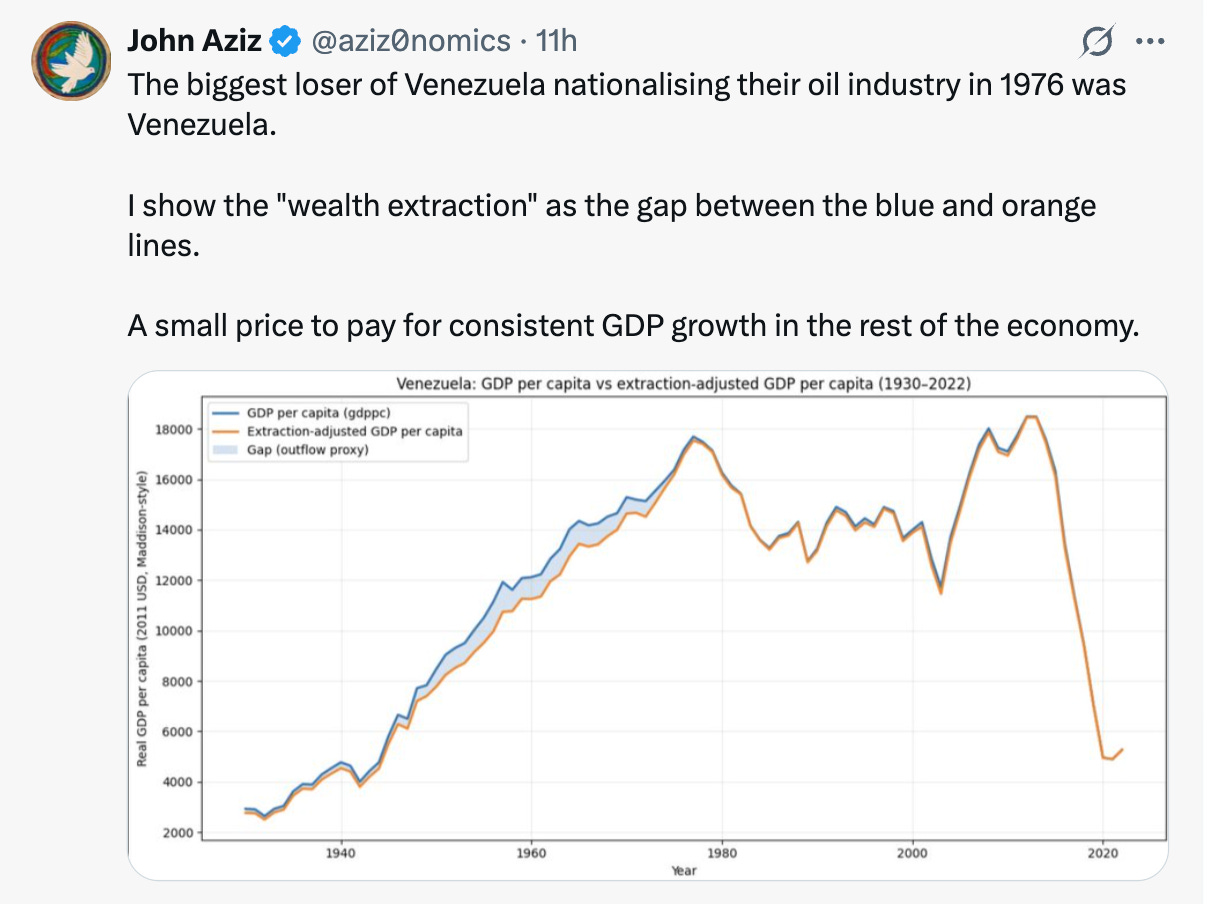

A lot of people have been talking about how much valuable oil Venezuela does or does not have and what type it is. The graph below is very illuminating as to how carefully claims to huge reserves ought to be handled. “Proved reserves” are not simply a natural fact.

There have been a large number of very long twitter comments on oil matters. I found the one below particularly useful in understanding how the extraordinary leap in Venezuela’s oil reserves happened in the 2010s. It is from Yellowbull @Yellowbull11

There has been lots of talk about the current situation in Venezuela and what it could mean for global oil markets, so I just wanted to provide some nuance on this When people say “Venezuela has the world’s largest oil reserves,” as you undoubtedly have seen being thrown around a lot on here, they are technically referring to a specific accounting definition, not to a stock of easy, cheap barrels ready to flood the market. To unpack that, you need to get into what those reserves are, how they behave in the subsurface, what it costs to turn them into marketable liquids, and how price, technology, and above-ground risk interact. That’s a lot to cover, but let’s give it my best shot. On paper, Venezuela has roughly 300–303 billion barrels of proved reserves, about 17 % of the global total and slightly more than Saudi Arabia. The critical detail is that around three quarters of that booked volume is extra-heavy crude from the Orinoco Belt in eastern Venezuela. These are bitumen-like oils with API gravity typically in the 8–14° range, extremely viscous at reservoir conditions and with high sulfur and metals content. So the statement “largest reserves” is really “largest booked volumes of very challenging heavy and extra-heavy oil.” Technically recoverable versus economically recoverable is the first big distinction. The USGS has long estimated that the Orinoco Belt contains on the order of 900–1,400 billion barrels of heavy crude in place, with perhaps 380–650 billion barrels technically recoverable using existing technology. Venezuela and OPEC only book a subset of that as “proved,” but even those proved numbers are sensitive to the assumed oil price and development concept. When prices were strong in the 2005–2014 window, a large portion of Orinoco volumes became economic on paper and were reclassified as proved, driving the headline reserves from ~80 to ~300 billion barrels. Geology and fluid properties are the second big differentiator. Orinoco crudes are extra-heavy, with densities up around 934–1,050 kg/m³, high asphaltene content and sulfur on the order of 3–4 wt% or more, depending on the block. This is a completely different animal from a 33–40° API, low-sulfur Arab Light-style crude. In plain English, that means it’s much harder to handle at various stages and each step adds capex, opex and energy use. In other words, the “barrel in the ground” in Venezuela is inherently worth less and depends on a narrower set of buyers. Surface systems and institutional capacity are another constraint. Before the 2000s, PDVSA had a reputation as a technically capable NOC. Since then, you have had a combination of mass layoffs and politicization, under-investment, sanctions, corruption and brain drain. The result is decayed gathering systems, chronic power shortages, refinery fires and upgrader downtime. Finally, integration with global refining and logistics matters for strategic value. Venezuela’s crude slate is optimized for complex “coking” refineries in the US Gulf Coast, parts of Asia and a few European plants. That’s a story for another time though, because the length of this analysis is getting out of hand. So when you hear that Venezuela has “the world’s largest oil reserves,” the technically accurate part is that the country has extremely large volumes of extra-heavy oil in place, and a big subset of that was once judged economically recoverable at high price assumptions and booked as proved. The more relevant questions for energy strategy are how many of those barrels are genuinely economic under realistic long-term prices, how quickly they can be brought onstream given infrastructure and institutional constraints, what netback they deliver at the refinery gate, and how exposed they are to being left in the ground if demand peaks. On those metrics, Venezuelan barrels sit much further out on the cost and risk curve than the headline “largest reserves” soundbite suggests.

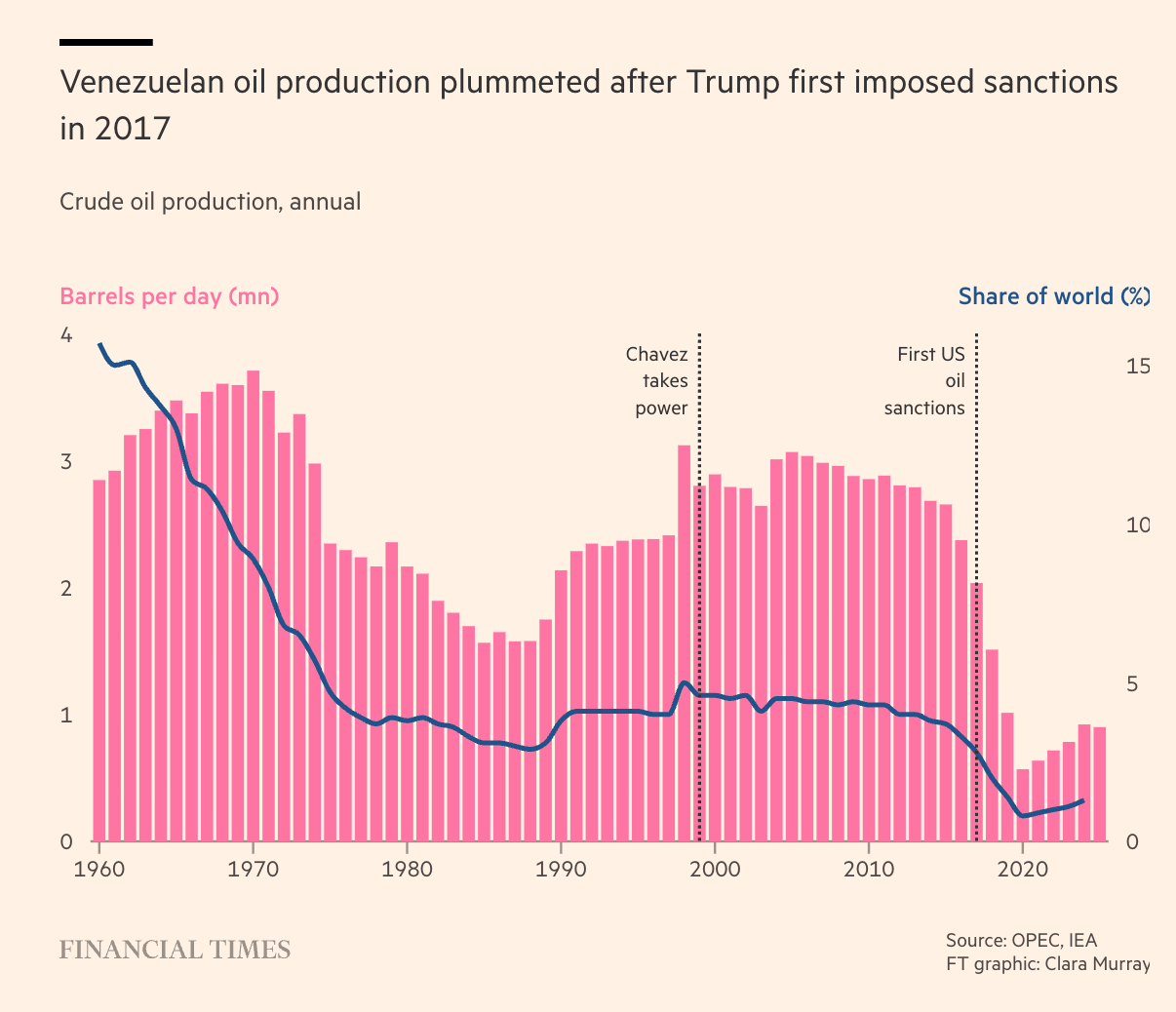

So what happened to the Venezuelan oil industry and when did it happen? Starting from this FT graph it would seem that this is a story in three parts. #1 The long decline in the 1970s. #2 The recovery of the 1990s leading to stabilization on a reasonably high plateau from the 2000s. #3 The collapse of the mid 2010s that began before but was massively amplified by sanctions applied under the first Trump administration in 2017.

The question that is most contentious right now is that of US property rights and claims to compensation by Exxon and ConocoPhillips. This would seem to be “the American oil” that Trump claims was stolen and that he now wants back.

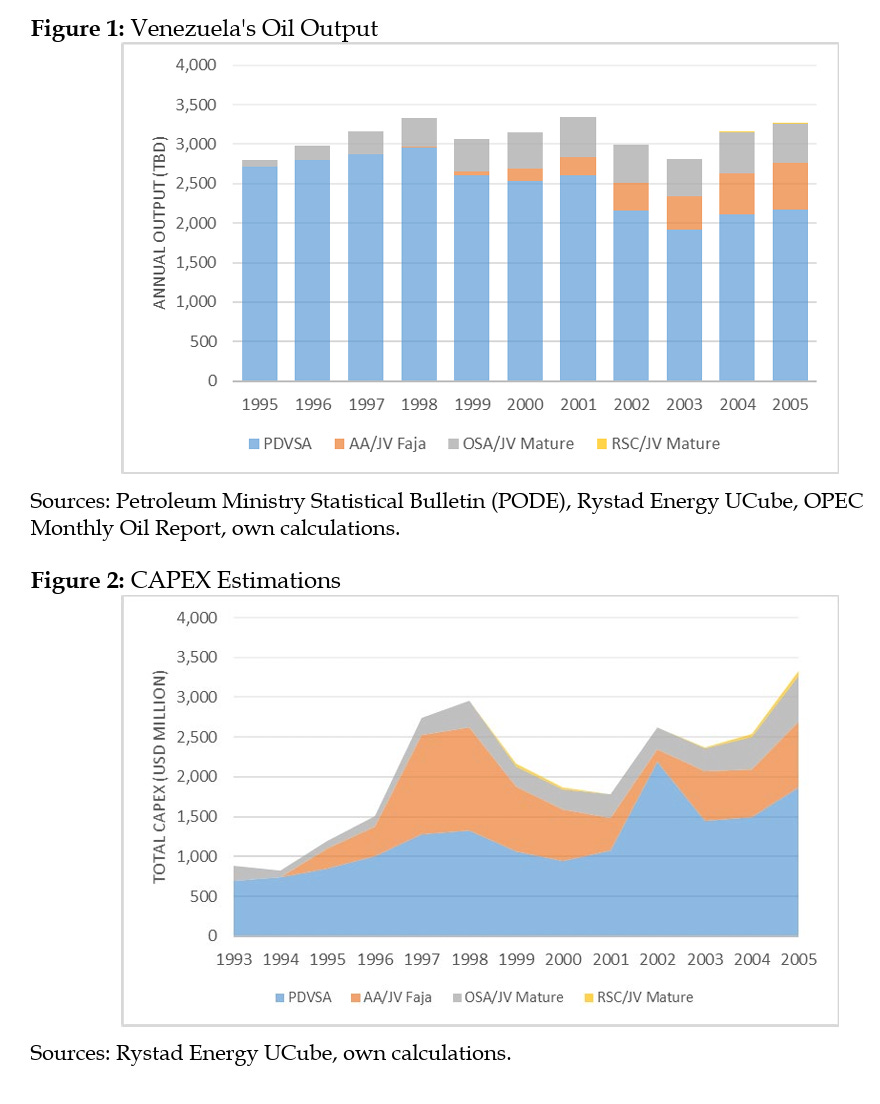

Obviously the story is more complicated and goes back to the (re)opening of the Venezuelan oil industry to foreign investment and technology - Apertura Petrolera - initiated in the mid 1990s. According to a report by Francisco Monaldi, PhD Fellow in Latin American Energy Studies, Rice University’s Baker Institute Igor Hernández Graduate Fellow, Rice University’s Baker Institute José La Rosa, MSc Research Analyst, Rice University’s Baker Institute, published by the Baker Institute (no innocents!)

The Apertura was a great success. Almost all the major international oil companies in the world invested in Venezuela. BP, CNPC, Conoco, Chevron, ENI, Exxon, Petrobras, Repsol, Shell, Statoil, Total, among others, made significant investments. In 2005, combined output from OSAs and AAs reached an average of 1.1 MBD. Projects developed during Apertura added an output capacity of 1.2 MBD. Rystad Energy estimates the CAPEX provided by private investors at USD 10.8 billion. Manzano and Monaldi (2008) estimated that the total CAPEX on the Apertura projects at $25 billion.

Source: Baker Institute

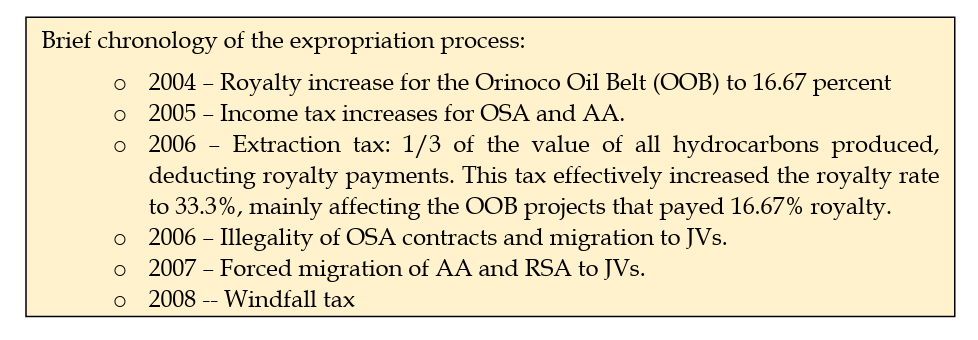

In the mid 2000s Hugo Chavez moved to change the terms of the 1990s deals

This forcible rearrangement has resulted in expensive litigation and huge awards to several of the investors. Some of the legal arguments are dissected in delicious detail in this fascinating report by Juan Carlos Boué

During the mid-1990s, Venezuela’s national oil company, PDVSA, implemented a policy known as the Apertura Petrolera (oil opening), which sought to mobilise the capital, technology and managerial capabilities of international oil companies in order to maximise the production of crude oil while simultaneously reducing drastically the fiscal burden on hydrocarbons exploration and production activities in the country. The Apertura achieved its objectives to a large extent, albeit in a fashion reminiscent of those operations which are hailed as a medical triumph though the patient winds up dead: production à outrance by Venezuela was a key factor behind the oil price collapse of 1998, and the paltry fiscal income generated by some of the Apertura-era projects made them the most unfavourable—for the State—in the history of the Venezuelan petroleum industry.[i] The standard-bearers of the Apertura were four large, costly and complex projects dedicated to the production, upgrading (i.e. partial refining) and marketing (as synthetic crude) of extra-heavy oils from the Orinoco Oil Belt (OOB), an immense reservoir with over 1 trillion barrels of dense—heavier than water—hydrocarbons in place. Today, three of these projects (Petrozuata, Hamaca and Cerro Negro) are at the centre of the arbitration proceedings that ConocoPhillips (COP) and ExxonMobil (XOM) initiated against Venezuela at the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) in late in 2007.[ii] These arbitrations feature some of the largest claims ever to have been brought against a state by international investors: US$30 billion in the case of COP and more than US$15 billion in the case of XOM. However, a careful reading of dispute’s factual background suggests that these claims bear little connection with the deals that these oil firms actually agreed to in Venezuela.

At the root of these arbitrations was the decision by the Venezuelan government to re-structure the OOB projects to bring them in line with the legal requirements and fiscal conditions applicable to all other companies with oil activities in Venezuela, as set out in the 2001 Organic Law of Hydrocarbons. This included a requirement that the projects be transformed into mixed companies in which PDVSA affiliates would have a shareholding of 60 per cent; to comply, COP and XOM would have had to reduce their equity in the projects by selling part of their stakes to PDVSA. The companies’ rejection of the government’s terms led to their exit from Venezuela, with PDVSA taking over their shareholdings completely The legal questions at the heart of these arbitrations are highly complex, and even explaining them in summary form took a paper running to around one hundred pages of text.[iii] And yet, paradoxically, XOM CEO Rex Tillerson says “[o]ur situation in Venezuela is a pure and simple contract. The contract was disregarded.”[iv]

In a nutshell, COP and XOM allege that, in changing the fiscal conditions for the upgrading projects, and then re-structuring them along the lines sketched above, the Venezuelan government rode roughshod over their vested rights, treating contractual undertakings “as the proverbial ‘scrap of paper’ that they can disregard at their convenience … breaking all the commitments … made to induce … investment.”[v] As to what exactly those commitments were, however, COP and XOM studiously avoid going into specifics, which is hardly surprising because key documents on the record show that these alleged commitments are figments of over-active corporate imaginations. The COP and XOM investments were only able to happen thanks to the legal régime d’exception defined in Article 5 of the 1975 Venezuelan Oil Nationalisation Law which—”in special cases and if convenient for the public interest”—allowed state entities to “enter into association agreements with private entities …. [with] the prior authorisation of the [Congressional] Chambers in joint session, within the conditions that they establish”.[vi] Among the numerous conditions that the Venezuelan Congress stipulated for all upgrading projects is one that is fatal in terms of the companies’ claims of governmental undertakings to the effect that neither the fiscal nor the legal framework of the upgrading projects would be altered. In the case of the Cerro Negro project, a joint-venture between XOM, PDVSA and British Petroleum,[1] this condition was expressed in the following language: “[t]he Association Agreement, and all activities and operations conducted under it, shall not impose any obligation on the Republic of Venezuela nor shall they restrict its sovereign powers, the exercise of which shall not give rise to any claim, regardless of the nature or characteristics of the claim…”.[vii] As can be clearly appreciated, this condition amounts to a full reservation of sovereign rights by the Republic (which, furthermore, was not a party to any of the association agreements).

There exist documents in the public domain, contemporary to the measures, which show that COP and XOM knew full well that their situation vis-à-vis the Venezuelan government was not one of “pure and simple contract”. These documents are of special interest because the statements and opinions contained therein were made in the belief that they would remain confidential, but which came out in the open with the publication of 250,000 US diplomatic cables by Wikileaks. One such cable reported that the petroleum attaché in the US embassy in Caracas was told by an “ExxonMobil executive … on May 17 [2006] that his firm did not believe it had a legal basis for opposing the tax increases” resulting from “amendments to the Organic Hydrocarbons Law (OHL) that raise income taxes on the strategic associations from 34 to 50 percent and introduced a 33.3 percent extraction tax.”[viii] This candid confession is irreconcilable with the fanciful COP and XOM allegations of fiscal guarantees. But the cable contains an even more revealing disclosure, which goes to the heart of the quantum of compensation COP and XOM are owed for the nationalisation of their interests, and makes a mockery of their colossal damages claims: … each of the strategic association agreements has some form of indemnity clause that protects them from tax increases. Under the clauses, PDVSA will indemnify the partners if there is an increase in taxes. However, in order to receive payment, a certain level of economic damage must occur. In order to determine the level of damage, the indemnity clauses contain formulas that, unfortunately, assume low oil prices. Due to current high oil prices, it is highly unlikely that the increases will create significant enough damage under the formulas to reach the threshold whereby PDVSA has to pay the partners.[ix]

Source IISD

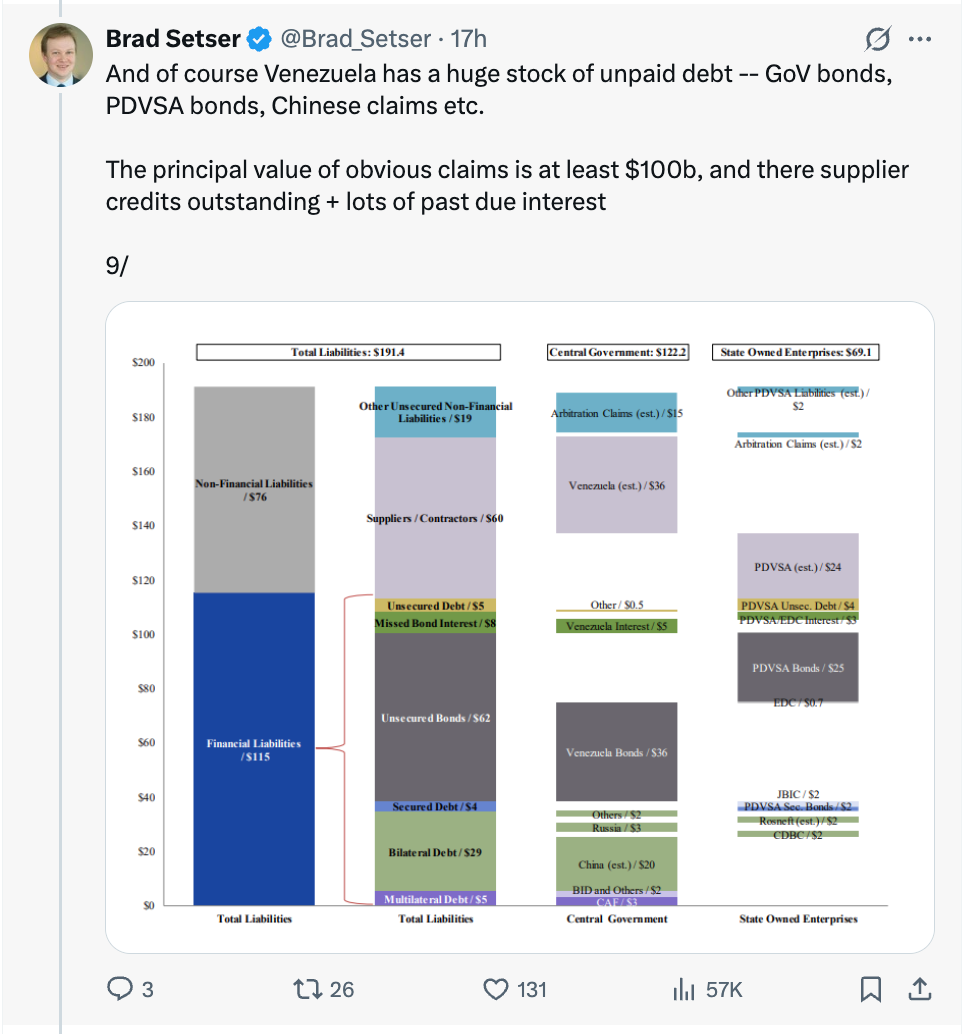

Whoever ends up “running” Venezuela and however they do it, money is going to be an issue. And when we are talking money there is one account you have to go to: The indispensable Brad Setser.

Source: SSRN

Simple conclusion: Anyone “running” Venezuela is going to end up not just with assets but also with a huge pile of liabilities.

I’ve been deliberately minimal in this post in the hope of offering some useful pointers rather than big noisy claims.

If I were to make a big noisy claim it would be that the entire exercise has less to do with actual resource imperialism than Trump’s feckless reality TV Cosplay resource imperialism. He likes demonstrative acts of violence. He likes to claim immediate economic paybacks. He singled out Venezuela in his first term. He has come back for more.

If you pushed me further I would say that the Trump administration appears to be serious about the Monroe … sorry Donroe … doctrine in the Western hemisphere. Could this be a prelude to an overt spheres of influence deal with China, Russia and Saudi-UAE-Qatar-Israel … possibly?

What next? It does strike me as plausible that there could be a faction around Marco Rubio whose real target for actual regime change is Cuba (note the Cubans killed in the US operation) rather than Venezuela.

But for now I’ll leave it there. Back to the manuscript!

I love writing the newsletter. Can’t wait to get back to even more active posting in 2026 when the book is done. In the mean time, if you fancy buying me a coffee once a month, you know what to do. Chartbook will keep on coming in any case.

brilliant and thank you! Makes me feel better that the future could be more difficult for the american regime than they imagine right now, caught up in their euphoria of violence. Reality may hit hard!

Trump might like to pretend the Russia is due a sphere of influence, but in actual reality Russia is fast becoming a vassal state of China. Russian influence in the Middle East and in Latin America has already gone kaboom, and any remaining European influence is hacked to bits in the killing fields of Pokrovsk and Kupyansk.