Chartbook 387: What fires burned at Auschwitz? On the place of the Holocaust in uneven and combined development.

“"We see railway tracks anywhere and think about Auschwitz," Anselm Kiefer reportedly remarked after painting Lot’s Wife. Once a cause for scandal, in recent years the association of the Holocaust with industrial modernity has become an entrapping cliché.

Start with what you might call “Eichmann’s Holocaust”, the Holocaust of the railway timetable, the Holocaust of the “cattle trucks”, mundane, wood-sided goods wagons of which the German railway system had more than a quarter of a million in circulation, vehicles which today stand in museums, as symbols of the horror, somewhere between metonym and synecdoche. The idea of a sinister organizer standing at the hub of a network of logistics and communications, directing mass death has wide resonance. So much so that it appealed to the perpetrators themselves. Think of Albert Speer’s self presentation at Nuremberg and after, or the sketch below, made by a mid-level SS manager in 1944, portraying himself, as he would later come to be imagined.

Source: Michael Thad Allen, The Business of Genocide. The SS, Slave Labor, and the Concentration Camps (2005)

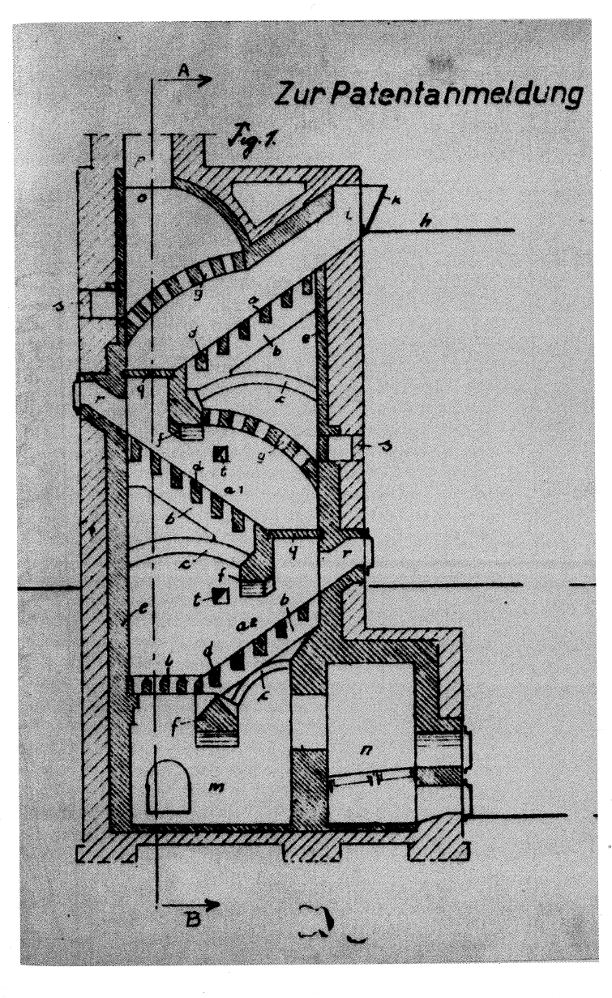

Then you have the killing centers themselves, the death camps where more than half of the six million victims of the Holocaust were put to death. What kind of places are these? As they emerge from Jean-Claude Pressac’s famous account of the Technique and Operation of the Gas Chambers (1989), the killing facilities at Auschwitz were archetypical industrial artifacts, designed by german engineers, inserted into the architectural ensemble of the camp. This you might say was the Holocaust of the blue print. The front cover of the catalogue which accompanied an exhibit in Berlin about Topf, the firm that built about half the crematoria in use across the camp system, illustrates this reading.

Then there is the notion of the “death factory”, a recurring description of the camps, which seems to have originated in Soviet sources perhaps as early as 1943. Trawling for the term online, one comes across the work of historian David Shneer on Dovid Bergelson (From Mourning to Vengeance: Bergelson’s Holocaust Journalism (1941—1945 (2007)), one of the most prominent yiddish writers in the soviet union. In Bergelson’s writing, the idea of the death factory emerges through his account of an encounter with a brutalized German perpetrator, a POW named Helmut.

“Helmut’s memory” Bergelson writes of the German captive anticipating arendts description of Eichmann “Helmut’s memory is exceptionally poor. He remembers only those things that were personally useful or painful to him. Instinctively, like a dog, he can visualize only those places where he pigged out, got drunk, and raped and also those places where he slaughtered many people ... but for example, it is very difficult for him to remember the name of the place in Poland from which he brought his “piece of Jewish soap” ... Helmut is asked where he got his soap. Helmut answers coldly “over there”. “From a soap factory?” “Of course” One really wants Helmut to talk more precisely about the process that takes place there in the “factory” where bodies of dead Jews are brought and converted into soap. But Helmut has little knowledge of these processes. They hold no interest for him. He is simply interested in getting his hands on one of the first pieces of that Jewish soap, so he can send it, as a curiosity, to his Ilse for her birthday and, as he would admit to himself, give her pleasure.”

Bergelson makes a move in this passage, that Arendt will later recapitulate: Turning away in disgust from the inadequate subjectivity of the perpetrator, Bergelson is drawn to the mechanism of killing - “one really wants Helmut to talk more precisely about the process that takes place there in the factory...”. But all Helmut can do is to ramble on revoltingly about his German girl and the bar of “Jewish soap”.

In 1944 after the liberation of Majdanek, where the soviet troops discovered warehouses of shoes and human hair, the term “death factory” gained general currency. Through wartime propaganda channels the Soviet pamphlet, Majdanek the death factory near Lublin by Konstantin Simonov acquired a circulation in the West. In the exhibitionary complex of the holocaust, the shoes from the Majdanek warehouse have become another icon, especially since a large collection of them were donated to the Holocaust memorial museum in Washington DC.

As the researcher Joachim Neander showed in his remarkable essay - “"Seife aus Judenfett" – Zur Wirkungsgeschichte einer Urban Legend” - the soap myth is itself an instance of the conceptualization of the Holocaust as industrialism. The idea that the Germans turned their victims into soap originated in fact in the generation before the Holocaust in a fearful rumor that began to circulate at the end of World War I. As the economic situation of Wilhelmine Germany became desperate and POW along with Germans began to starve, rumors began to circulate that the Kaiser’s regime was rendering the bodies of Belgian and other prisoners of war to make soap. After all, Germany was commonly regarded as a great industrial power with a particular talent for industrial chemistry, ranging from artificial fertilizer to poison gas. This atrocity story was then picked up in the 1920s, as part of the self pitying imaginary of the German far right. So that when the invasion of Poland began in 1939 it was German troops who took to terrorizing both Poles and Jews they encountered with the jocular taunt that now they really were going to turn them into soap. The story spread rapidly around Poland in 1942 and reached the West where it was investigated by Rabbi Wise, which in turn triggered Himmler into his own enquiries to establish that no such activity was in fact taking place in the SS system.

Which of course begs the question of what the bar of soap was that the Red Army found on Helmut and that Helmut clearly believed to be Judenseife? It is conceivable but vastly unlikely that Helmut had got his blood-stained hands on one of the small batch of experimental soap bars which were made from human cadavers at Stutthof camp. But Himmler’s orders made clear that no mass production was ever authorized or approved. So the most probable interpretation is that Helmut was carrying around the kind of bars of soap that were subsequently exhibited in trials and museums after the war and featured in small shrines to the Jewish dead.

The soap displayed here was produced in Germany and bears a stamp which could be mistaken for RJF, which might in turn be read as Reichsjudenfett or, more grotesquely as Reines Juden Fett (pure jewish fat). In fact, the middle initial is not a J but an I, and the acronym stands for Reichsstelle fuer industrielle Fette - national agency for industrial fats. The soap was, as in world war I, a mass produced ersatz product necessitated by Germany’s desperate shortage of raw materials, boiled together from industrial byproducts.

RIF or RJF, the idea of corpses being turned into raw materials has had a powerful and continuing attraction as ways of thinking about the Holocaust. A particularly striking instance is Moishe Postone’s essay “Anti-Semitism and National Socialism”, New German Critique (1980), which not only takes the soap story at face value but makes it serve as the logical conclusion of a complex account of the ideological logic of the Holocaust. Taking up Marx’s concepts of fetishism, Postone argues that anti-semitism is in a sense the ultimate product of commodity fetishism, a radical political movement directed against the Jews, as the arch representatives of global money. For Postone: “Auschwitz was a factory to "destroy value," i.e., to destroy the personifications of the abstract. Its organization was that of a fiendish industrial process, the aim of which was to "liberate" the concrete from the abstract … to eradicate that abstractness, to transform it into smoke, trying in the process to wrest away the last remnants of the concrete material "use-value": clothes, gold, hair, soap. Auschwitz, not 1933, was the real German Revolution … “.

If the concentration camps did not in fact produce soap this has not prevented another chain of associations around the idea of the factories of death, the association with the slaughter house. Siegfried Kracauer first suggested the analogy between the death camps and the abattoirs. But it was taken up with real gusto by Daniel Pick in his 1993 book War Machine, which argued that already in the 1860s “technology, factory production and death” were coming together in new ways. He echoed Martin Heidegger who in 1949 infamously allowed himself to be recorded declaring that:

Agriculture is now a motorized food-industry — in essence, the same as the manufacturing of corpses in gas chambers and extermination camps, the same as the blockading and starving of nations [the Berlin blockade was then active], the same as the manufacture of hydrogen bombs

It is interesting that Heidegger analogized between slaughter houses, Auchwitz and the manufacture of hydrogen bombs, not their use. In an alternative tradition that traces back to the Frankfurt school, it is not the manufacture of weapons of mass destruction, but their use that is compared to the camp. Following some rather offhand remarks by Adorno, the association of Auschwitz and Hiroshima is almost routine. The common denominator, it is suggested, lies in the extreme violence, the distancing between killer and killed and moral indifference implicit is the subject-object relation between perpetrator and victim.

Each of these clusters of associations - infrastructures of railway movement, sinister maps and blue prints, obscene factories for the rendering of the human body, the day to day obscenity of slaughter, firestorms and bombs - has currency because they have at least a superficial logic and a plausibility. But what we should put in question, is the intellectual earnestness of their proponents. What these modes of thinking have in common is a combination of drama and banality. Noisiness and emptiness combine to form a self-protective mix that numbs the critical senses. To counter this I propose in what follows, to tear these analogies out of the safety of their abstractions and to subject them to a somewhat brutal exercise in literalism.

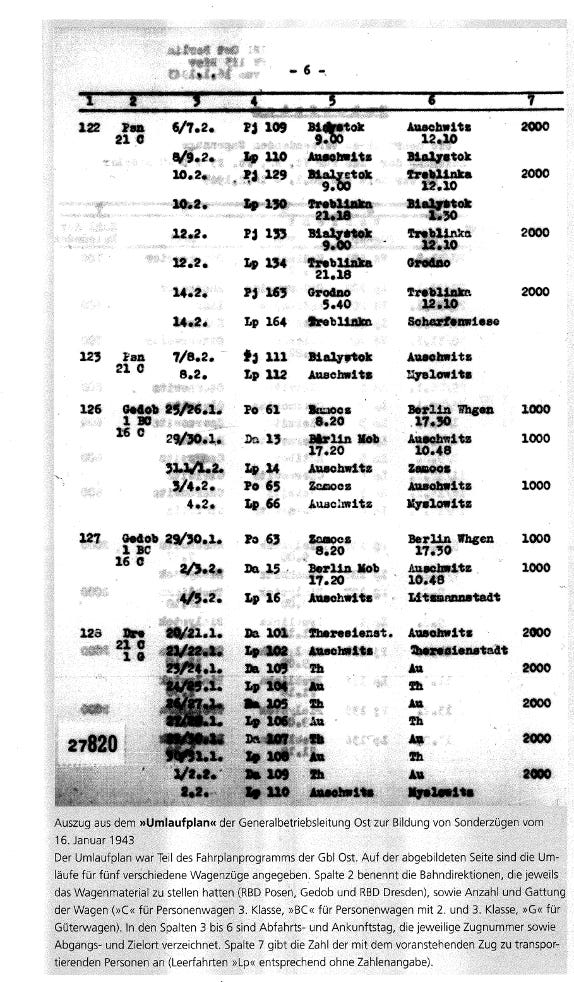

But first let me try to explain what I mean by their formulaic quality. Take for instance this illustrative page of a historical volume documenting the German railway’s involvement in the Holocaust.

The impact on the casual reader is something like this: Here is a timetable. It is full of codes and euphemisms. Codes, euphemisms and timetables are bureaucratic. Bureaucracy is modern. This timetable references Auschwitz and Theresienstadt. It belongs to the Holocaust. The holocaust is modern. And perhaps it even follows that without euphemistic, coded timetables like this the holocaust would not have been possible. And as Kiefer suggested, whenever we now see railway tracks and timetabling codes we may think of Auschwitz.

In principle one cannot simply dismiss such argumentation. It is not completely wrong. Trains do run on timetables and if you have to move a lot of people in 1943 trains were your best option. But in following these kinds of trains of association, I would suggest that we are engaging in thought processes which can be fairly described as dealing with surface manifestations of modernity, as a play of symbols, patterns and appearances. We are being invited by illustrations of this kind, to hold these objects at a distance, to look AT these pictures, to shut one eye and to draw conclusions on the basis of their general outline. What we are not doing is really looking INTO them, actually examining them in their specificity, their technical detail, their content. We look AT the timetable, we don’t read what is IN the timetable. We treat the timetable as a symbol of modernity rather than deciphering its actual function as a link in production of bureaucratic power.

This distanced, formal mode of reading, has its uses. It is a way of “holding things at a distance”, “not getting caught up in the logic of power” etc. But what if we, for a moment were to drop our now habitual guard as self-declared ethnologists of modernity and to engage in what might be called a naive reading. Let us take the document at face value. Let us approach the timetable not as amateur cultural sociologist but instead as apprentice railway timetabler. With a little effort you can learn to read what these documents actually are saying. In the first few lines of the document above we read how Special Train 122 to be provided by the Posen Reichsbahn directorate was between 6/7 February 1943 and 14 February to shuttle between Bialystok, Grodno, Auschwitz and Treblinka, taking 8000 people to their deaths, 2000 at a time, with empty runs between the camps and the ghettoes. That is certainly concrete, but also too specific to be of much interest, unless you are trying to identify who was on those trains. But aggregate back from there, to a more general understanding not just of the fact that the Holocaust had a railway timetable, but what that timetable was and we have the key to a far deeper understanding of how the mass killing of the Holocaust, actually sit within modernity.

What is unsettling about this, is that knowing not only that the Holocaust had a timetable, but also knowing what the Holocaust timetable was - it consisted of roughly 200 pages like the one above - shifts our position. It places us no longer in the distanced vantage point of the critical theorist, but in the place of the perpetrator, or the detective - When did that train go from B to A? This kind of question is habitually the realm of “lower” forms of knowledge - the obsessive reenactor, the simulator, the hobby historian, the genealogist, the chronicler. But it is also the vantage point, we must insist, of a genuinely critical political economy. Taking the numbers seriously opens the path to talking about the relationship of the Holocaust to industrial modernity in more than a merely gestural sense. It allows us to calibrate and specify, it enables us to articulate their relationship.

Let me start with transport. And not with an image like that of the Kiefer but with “railway history” and in particular the specialist work of Alfred Mierzejewski, Hitler's Trains: The German National Railway & the Third Reich. Knowing a lot about trains, Mierzejewski does the obvious thing. He traces the trains allocated by the Reichsbahn and Ostbahn for the Jewish transports, to gauge their systemic impact. By his estimation, for all the long-distance transport involved in the Holocaust - for perhaps 3 million victims of the camps - 2000 train trips were necessary. 2000 trains is the complex that Eichmann presided over and earned him the starring role in Arendt’s account of the banality of evil. Of these transports over one thousand have been individually documented, 14 of them are shown in the table above. All in all Auschwitz received perhaps 613 and Treblinka 390 trainloads of victims. Treblinka, which was the highest intensity killing facility, was sited on the main, double-track line from Warsaw to Bialystock, which had been improved not so as to serve the camp, but so as to meet the massive logistical demands of Army Group Centre on the eastern front. Between August and early December 1942, at the peak of its short period of operation, 3 transports daily arrived at the railway siding in Treblinka. The timetabling for Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor had to be reasonably precise because these facilities had no holding pens. They were death camps. Not concentration camps. They were in the jargon of modern logistics, just in time operations. There were no buffers. People had to be killed on arrival. Specifically, it was important that the transports should arrive at Treblinka before noon, since otherwise it was impossible to kill everyone on board by nightfall. Likewise, we can see in the scheduling of long-range Dutch deportations to Belzec and Sobibor, the mind-boggling consideration that since those death camps did not operate on weekends it was crucial for the Dutch Jews to be despatched eastwards by Tuesday evening at the latest.

But grotesque as such details are. They are obviously not the main point. The main point concerns quantity and scale. The essential point about the Eichmann legend is that he accomplished something large and historically impressive. The entire burden of the Arendtian version acquires its force from the contrast between the awesome scale of what he perpetrated and vapidity of his personality. Likewise Moishe Postone explicitly invokes the scale of the transportation effort as part of his insistence that “the Holocaust was its own goal. ... No functionalist explanation of the Holocaust and no scapegoat theory of anti-Semitism can even begin to explain why, in the last years of the war, when the German forces were being crushed by the Red Army, a significant proportion of vehicles was deflected from logistical support and used to transport Jews to the gas chambers. Once the qualitative specificity of the extermination of European Jewry is recognized, it becomes clear that attempts at an explanation dealing with capitalism, racism, bureaucracy, sexual repression, or the authoritarian personality, remain far too general.”

And yet the very first thing you see as soon as you actually take these numbers at all seriously is that this basic narrative of the Holocaust, the claim that its moral and political weight was somehow expressed in its logistical demands, is fundamentally misplaced.

If Treblinka, at its height of its operations, was receiving three trains per day, this would amount to a daily load of 150 standard G-model covered goods wagons. As horrifying as this was as a site of mass murder. In logistical terms it was trivial. Every single day, day in, day out, the Reichsbahn despatched around 120,000 wagons. Treblinka in other words, consumed at the height of its operations, a few minutes per day of the Reichsbahn’s transport capacity, one tenth of one percent of the Reichsbahn’s freight capacity. Even on the line that immediately served Treblinka, the camp’s human cargo occupied a small fraction of capacity - 3 trains per day as against a total capacity of 72 trains per day. Contrary to Postone’s claim to priority, during 1942, when the battle of Stalingrad was raging, the logistical needs of the Wehrmacht had absolute priority, with 30-40 trains daily along the Treblinka line. Over the winter of 1942-1943, the SS found their transport allocation cut altogether for no more important reason that to allow Germany’s soldiers to spend Christmas with their loved ones.

And these were routine operations. For really high priority missions, the Reichsbahn was capable of logistical feats on a scale beyond anything Eichmann could ever imagine. One such feat was performed in 1941 in the build up for the invasion of the Soviet Union. Operation Barbarossa was the biggest land war undertaking in history. It involved the simultaneous deployment of 3 million men and their heavy equipment to a front line stretching over more than 1000 km. More than 120 divisions were involved. Moving an infantry division involved 70 trainloads, a panzer division required 100. In five successive waves between 25 February and 23 June 1941, the Reichsbahn deployed 33,000 trains, 11,784 for the combat units, the rest for support. On 7 June 1941 at the absolute peak of the effort, the Reichsbahn deployed 2588 trains eastwards. That is 25 percent more on a single day, than Eichmann organized over his entire career.

Given these brute proportions, the idea that the Holocaust impinged in any significant way on the logistical apparatus is simply far fetched. If we think of the transport effort of the Holocaust as 3 million one-way journeys, a glance in the Reich’s Statistical Yearbook tells us that every year 1.5 billion trips were made on the Reichsbahn. If we allow a total of 4 billion normal passenger journeys during the period of the Holocaust, this means that roughly one in every 1300 Reichsbahn passengers was a victim destined for the death camps. On every crowded commuter train, one single solitary passenger was destined for death.

Infamously, once they reached the East, the victims of the holocaust were typically transported not in passenger carriages but in enclosed G-type freight wagons used amongst other things for cattle. We have seen Heidegger pontificating about the essential identity between modern industrialized agriculture and the Holocaust. But, beyond coy and generalized associations, what would it mean to take this idea seriously? If you actually want to know about the industrialized killing of animals and to draw parallels to the Holocaust the data are readily to hand. On any given day in the early 1940s, the Reichsbahn moved over 41,000 head of cattle to market and from there to slaughter. And the Reich’s statistical office helpfully provides the basic metric with which to convert one animal body into another: average slaughter weight.

In 1936 the weight of the average oxen when slaughtered was a massive 327 kg. That of a bull was 323 and a cow 252 kg. Calves came in at 43 kg. Pigs at 99 kg. Sheep at 25. Goats at 19 and horses at 263 kg. The SS in their incinerator designs assumed 70 kg for the average human cadaver. So, with human cargo somewhere in size between a calf and a full-grown pig, the existing daily cattle movement capacity of the Reichsbahn was at least 70-80,000 human-equivalents, easily enough to absorb the Holocaust deportees in a few week’s of effort.

And - having taken the gloves off - why not take this obscene series of parallels one step further. Oxen, cows, calves, pigs, sheep, goats and horses were transported to slaughter, en masse, every day, in hundreds of well-documented slaughter houses for all of which we have meticulous data. So we know that in 1936 the slaughter-house of the city of Berlin processed 113,000 grown cattle, 227,800 calves, over 1 million pigs and almost 450,000 sheep. Munich slaughtered roughly half as many animals. Across the whole country the annual slaughter took over a million cattle, 1.5 million calves, 5.7 million pigs and 865,000 sheep. Clearly, it is true that modern society in their ordinary interactions with nature mobilize an awesome killing capacity. But somewhere early on, as your mind spirals out in obscene circles, you realize why the Holocaust was something different, why the easy analogy of animal and human slaughter is truly perverse, and why Heidegger’s bland apologetics hide an unthinkable thought.

Though every major German city did have the capacity for mass killing on an industrial scale, the Holocaust was not actually done in hygienic modern slaughterhouse facilities. The Holocaust was many things, but it was not an act of cannibalism. From an industrial point of view, it was something far cruder and less technologically demanding than the gory but sanitized flow of the meat supply-chain. People were delivered, regardless of condition. They were killed in large part with cheap industrial poison. The main problem on site was disposing of the bodies.

And once again the slaughter house analogy returns. It was in relation to slaughter houses that industrial society had first faced the question of what to do with animal carcasses, the flesh having been removed, that contained as much as 70 percent water and insufficient fat to burn well. The result from the late 19th century was the development of an industry of incineration that in the German case merged with crematoria, which by the early 20th century had became the fashionable alternative to burial. The first incinerator complex installed at Auschwitz at the end of 1940 was derived directly from these forerunners. It was not designed for continuous operation. Again we must not just stare at this. We must ask the question. What kind of fires were those that burned at Auschwitz? Where do these fires stand in the history that stretches back to one of humanity’s most basic discoveries.

If you read Pressac closely, with an eye to technical detail, you learn that it was rated at 70 bodies of 70 kg per day i.e. 4900 kilograms of combusted mass. In combustion the key is the volume of oxygen. And the first incinerator at Auschwitz had a ventilator system rated at 3 horsepower and capable of evacuating 4000 cubic meters of air per hour. By 1944 the incinerator systems of Auschwitz had expanded considerably. Their daily capacity was 3,250 standard bodies of 70 kilograms, a burned weight of 227.5 tons per day. But this was not a single powerful incinerator complex. It was a ramshackle system of five crematoria buildings none capable of disposing of more than 1000 bodies. Scanning the plans I can see provision for nothing more powerful than a ventilator of 5 horsepower with capacities at a maximum of 8000 cubic meters per hour. The significance of this dispersion and the underpowered ventilator systems is that with such modest blower capacity, burn temperatures are low, the burn rate is slow, the “waste” build up is significant, which in turn led to repeated breakdowns.

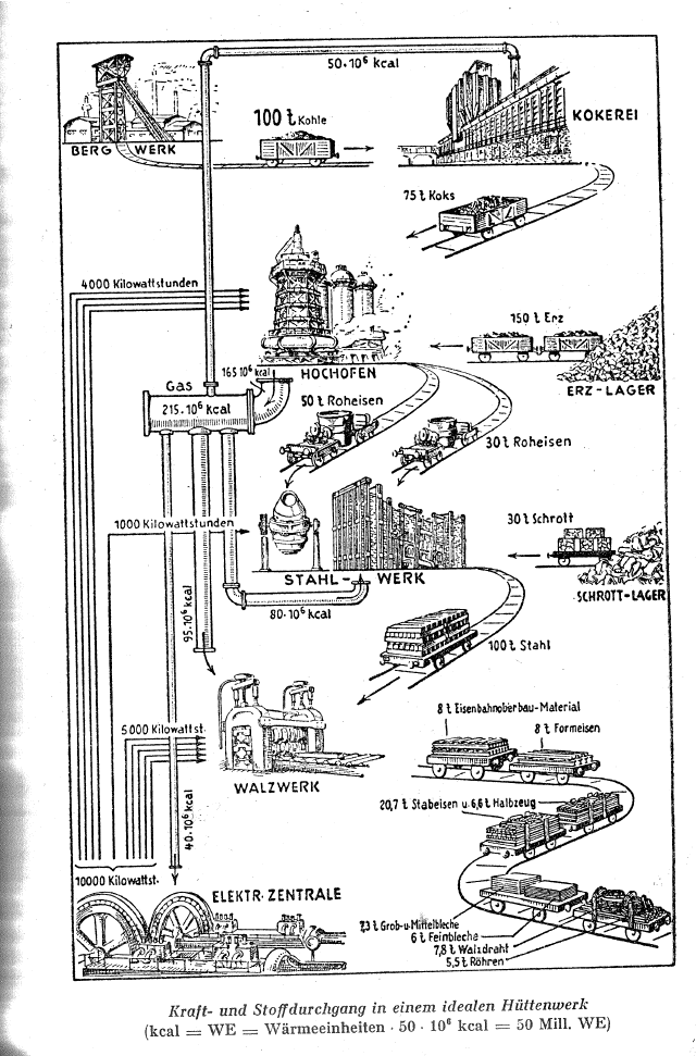

Compare the crematoria at Auschwitz, so often casually elided with factories, compare these fires with an actual industrial combustion process. Take, for instance, a blast furnace of the 1940s, of which Germany had 120 in continuous operation. A mid-century blast furnace was an enormous apparatus designed to consume every day 2-3,000 tons of iron ore, several hundred tons of calcium and perhaps as much as 1,200 tons of high quality coking coal. That is a total mass of combustion in the order of 4000 tons per day, compared to the 227 tons of incinerator capacity at Auschwitz.

A blast furnace is not a camp fire or a BBQ. It is a carefully managed fire storm. To burn at the precisely controlled temperatures of 1700 centigrade, a blast furnace is force-fed with air, preheated to 700-800 degrees Celcius. Huge engines, rated at 3000 hp or more, propelled by the waste gasses from the inferno, force fresh oxygen into the flames at the rate of 156,000 cubic meters per hour, a thousand times more powerful than the puny ventilators that left the crematoria at Auschwitz clogged with unburned residue.

The fires burning in blast furnaces live epic lives. One furnace was extinguished in the Ruhr in 1942 that had been burning continuously for 14 years.

Lacking priority in the war economy, the SS never had the fuel for such fires. Tellingly, the one significant technological innovation, for which a patent was later filed by Topf, involved a self-firing incinerator complex. After 2 days of preheating with fuel, the idea was that the flow of cadavers down the shoot would sustain itself in a continuous combustion process, thus saving fuel. The plan was never adopted and was subject to devastating criticism from within Topf. Because of the low heat at the top of the pile, critics warned that the slides would become caked in unburned matter.

Far from operating a significant “industrial operation”, what the SS ended up relying on were upgraded ovens of the type used prewar in cemeteries and municipal waste disposal sites.

The SS, despite its pretension to be a major player in the economy of Nazi Germany, operated its killing centers on highly restrictive budgets. The total investment in the camp complex at Auschwitz was c. 20 million Reichsmark. Most of that was for structures. A wood barracks cost in the order of 15,000 Reichsmarks. Stone buildings were more expensive. Crematorium II one of the two larger facilities cost in total 554,500 RM. Crematorium IV with half the capacity came in at 203,000 Rm. That is roughly the same as one heavy tank. Each crematorium oven unit with four to 8 chambers and ventilation came to less than 20,000 Reichsmark, the same price as a single artillery piece, of which the Wehrmacht ordered thousands per month. Even for Topf, the crematorium supplier, SS orders made up no more than 3 percent of its business.

At Auschwitz itself, it was not the camp or the extermination center, but IG Farben’s giant chemicals factory that represented a significant industrial wager. Compared to the 20 million Reichsmarks invested in the camp, IG Farben may have sunk as much as 600 million into the giant synthetic chemicals facility. The allied strategic bombing effort, to which the Holocaust is sometimes compared, cost the British not tens of millions of Marks, but ten percent of their total GDP. For a single large raid, the highly trained crews, the munitions and aircraft and air fuel represented perhaps 15-20 times the investment made at the mass killing facilities in Poland. When taken seriously as a technological proposition, the comparison of Auschwitz to Hiroshima is even more grotesque. On the development of the atomic weapons program, the US military lavished 2 billion dollars and mobilized the most brilliant scientific minds of a generation, concentrated in a giant technoindustrial complex stretching across a continent. Oppenheimer, as he unleashed the unprecedented inferno of the Trinity Test, was worrying not about unburned residue, but whether he was touching the divine power of creation and destruction.

The Holocaust was the most intensive and directed campaign of mass murder in world history. It had a truly singular logic. But it is a fallacy to imagine that this moral and political weight had a material counterpart of equal significance, involving major material trade offs, or expressing a deep relationship to the history of industrialism. If Arendt was right in insisting that an adequate account of the Holocaust must go beyond melodrama and sentimentality to a clear-eyed account of modernity, then we should be similarly clear-eyed in refusing banal cliché about what modern industrialism entails. Nazism’s ramshackle genocidal apparatus, was neither “backward” nor was it the ultimate telos of sophisticated technological developments It was carried out with a combination of banal elements of everyday modernity - barbed-wire encircling prefabricated wooden barracks, crude gassing and incinerator facilities, sited on obscure sidings of busy railway lines or next to high-priority industrial facilities. If the Holocaust is part of the history of modernity it is not because it was at the “cutting edge”, but because modernity is defined by the “contemporaneity of the uncontemporaneous”, by uneven and combined development. In this sense the coincidence of the Final Solution and the Manhattan project is significant, not for their identity, but because of the juxtaposition of two such incongruous projects of modern killing.

"Once the qualitative specificity of the extermination of European Jewry is recognized, it becomes clear that attempts at an explanation dealing with capitalism, racism, bureaucracy, sexual repression, or the authoritarian personality, remain far too general."

I'm afraid you gloss too quickly over Postone's observations, and get lost in the accounting ledger.

Sweeping abstract characterizations of the Reich as a whole, analyses of the logistics involved in murdering millions, miss a fundamental psychological reality- *the methods of extermination are the product of ruthless intent*.

Whether put up against a wall and shot, hung in public executions, or through engineered starvation, all were effective in accomplishing the purpose, and were employed throughout occupied Europe. The gas chambers were emblematic precisely because they required relatively crude, cheap technology. The Nazis were trying to find the least expensive, least time consuming manner for perpetrating genocide.

The ethnic cleansing was not in support of the Nazi war effort, the Nazi war effort was in support of the desired ethnic cleansing.

We know this because that is precisely what the Nazi's themselves said, over and over.

I think too much is made of Arendt's observation that Eichmann was dull-witted and shallow, and in fact I think she made too much of this, maybe because she was a brilliant person with brilliant friends and associates, trying to make sense of how millions could be mobilized in the service of committing atrocities for the sake of committing atrocities.

I find the words of Primo Levi (Italian Jew, Nobel winning author, and Auschwitz survivor) always clarifying in this regard-

"Before the Nazis started using the gigantic multiple crematoriums, the countless bodies of the victims- who had been deliberately killed or succumbed to deprivation and disease- might have been evidence and had to be somehow disposed of. The first solution, so macabre one hesitates to describe it, was simply to stack the bodies, hundreds of thousands of them, in large common graves. This was done chiefly at Treblinka, in other smaller camps, and behind the lines in Russia. It was a temporary solution, adopted with brutal nonchalance at a time when the German armies were triumphant on every front and the final victory seemed certain: they could decide what to do about them later, since in any case, to the victor goes possession of the truth, which he can manipulate as he pleases. Some way would be found to justify the common graves, make them disappear, or blame the Soviets... The prisoners themselves were forced to dig up the pitiful remains and burn them in open fires, as if an operation of such proportions, and so out out of the ordinary, could completely escape notice.

The SS commanders and the security services went to great lengths to make sure not a single witness would survive. This is the meaning (it is hard to imagine another) behind the deadly, and seemingly insane, transfers that brought the story of the Nazi camps to a close, in the early months of 1945: the survivors of Majdanek were transferred to Auschwitz, those of Buchenwald to Bergen-Belsen, and the women of Ravensbruck to Schwerin. The point was that all of them had to be removed from the liberation and redeported toward the heart of Germany under invasion from the east and west. It didn't matter that the prisoners died on the way; what mattered was that they not tell the story. In fact, after operating as centers of political terror, then as death factories and subsequently (and simultaneously) as bottomless pools of ever-replenished slave labor, the Lagers had become dangerous for a dying Germany, because they contained the secret of the Lager themselves, the greatest crime in the history of humankind. "(from The Drowned and the Saved)

Ruthless intent, conscious, calculated and depraved. For no other purpose, and for which there is no other, greater meaning to be discovered.

This is the lesson that gets lost in the shuffling of numbers and the parsing of histories of the Reich.

I think of Auschwitz and I think of those that did not cry out GENOCIDE.

And the promises I made to myself on my visits that thank god there will be no more genocides but if there will be I must stand up and call it out.

And I think of the German grandchildren 50 years later asking "did you know?"

Modernity 2025 seems to be about deception. State deception making permissible self-deception. Not much different from modernity 1940.