Chartbook 368 “I have only committed the mistake of believing in you, the Americans.” The day after Trump's "Liberation Day" in SE Asia.

“I have only committed the mistake of believing in you, the Americans.”

I wasn’t looking for that poignant quote this morning. But there it was on the front page of The Diplomat magazine.

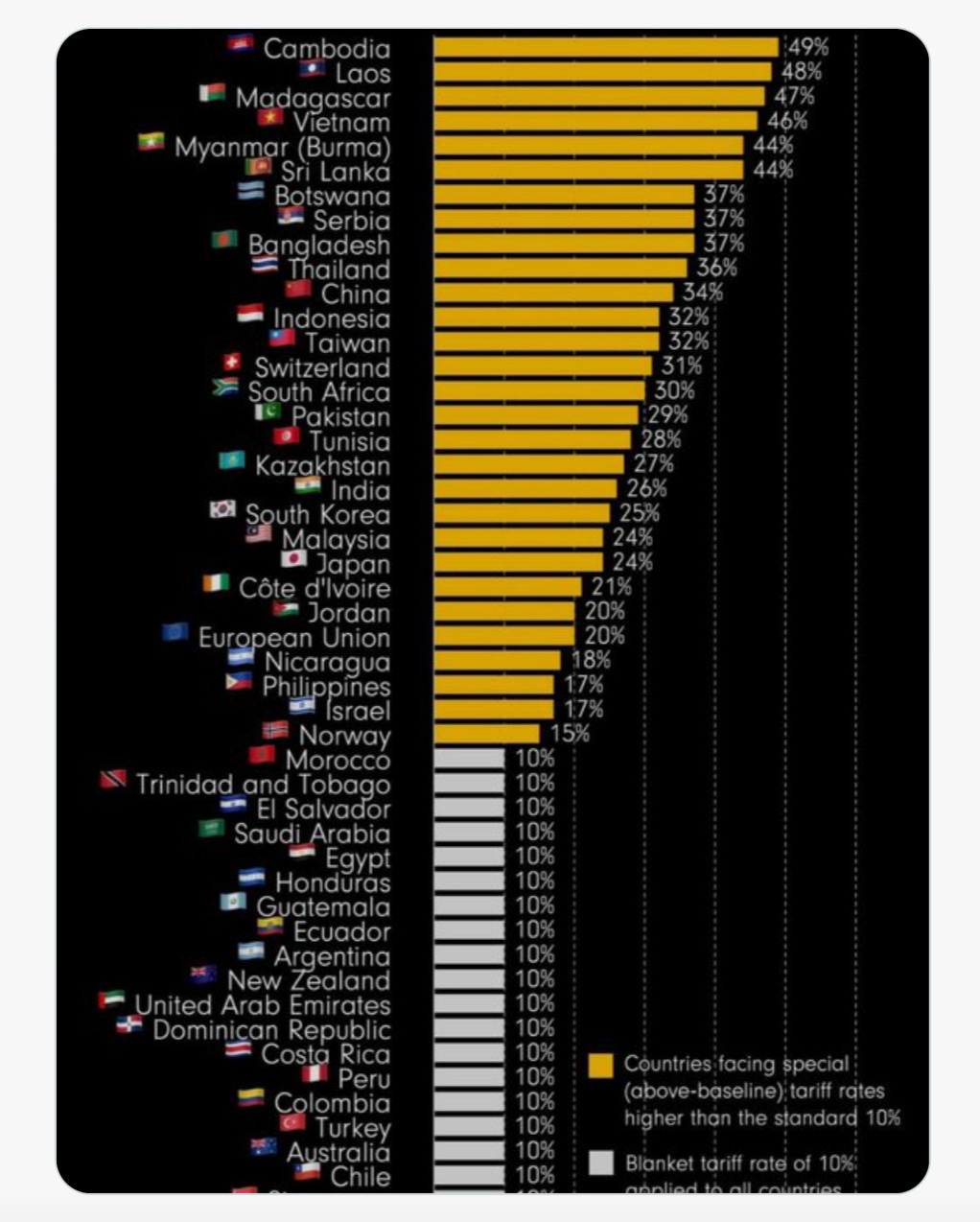

I subscribe to the Diplomat above all for its excellent coverage of South East Asia. I was looking for analysis of the impact of Trump’s grotesque tariff announcements on South East Asia: 49% Cambodia; 48% Laos; 46% Vietnam.

But The Diplomat, being the wide-ranging news source that it is, even in these days has other things on its mind, notably, the fiftieth anniversary of the fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge in April 1975.

And there they were, the words of a letter from Prince Sirik Matak to then-U.S. Ambassador John Gunther Dean, from a letter dated April 17 1975, words that are habitually shared by Cambodians on social media at this time of year.

Declining the American ambassador’s offer of asylum in the United States Sirik Matak wrote:

“As for you and in particular for your great country, I never believed for a moment that you would have this sentiment of abandoning a people which has chosen liberty. You have refused us your protection and we can do nothing about it. You leave us and it is my wish that you and your country will find happiness under the sky. But mark it well that, if I shall die here on the spot and in my country that I love, it is too bad because we are all born and must die one day. I have only committed the mistake of believing in you, the Americans.”

You might suspect that I am making this up for dramatic effect, but here is the screenshot:

Note also the item further down: “No Time to Waste for Asia-Pacific Leadership.”

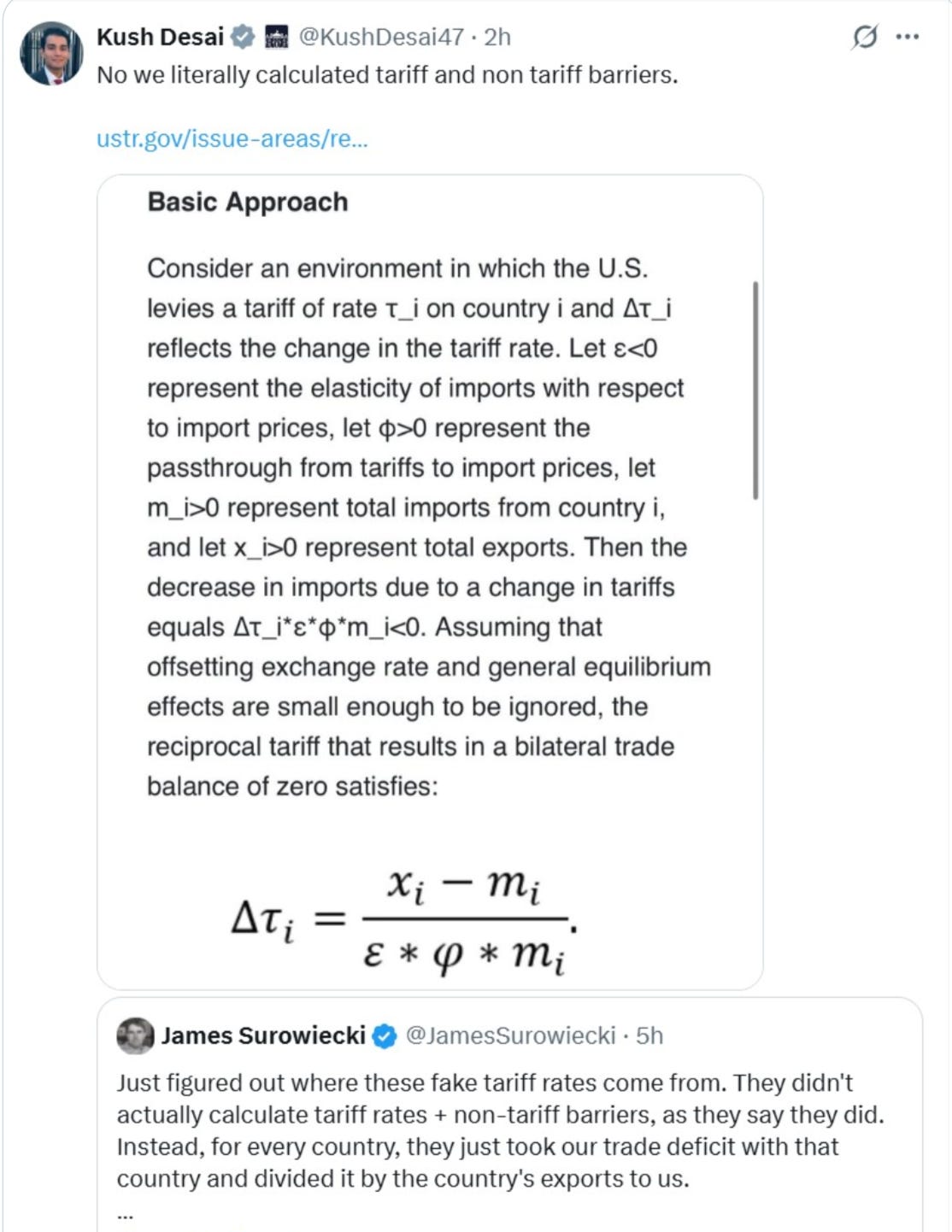

Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos are all at the top of Trump’s tariff hit list not because they impose high tariffs on the US, but because the Trump administration used an absurd formula to calculate its “reciprocal” tariffs.

Despite the obfuscations of the Trump press team, as the official US account shows, the formula starts not with tariff rates but from the trade surpluses recorded by each trading partner. This surplus was then divided by the total bilateral trade, to gain a measure of the imbalance. In Trump-speak this is a measure of the degree to which the country was “ripping America off”. Because the President wanted to send a message, but also to show his magnanimity, the US then applied a discount rate of 50 percent to the “tariff”, arriving at what it is calling “reciprocal tariff rates”, unless the minimum tariff of 10 percent was greater, in which case that is the rate that applies.

The rates for Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos are so high because they have a large trade imbalance with the United States. This is not because they discriminate viciously against American exports, but because they are relatively poor. The United States does not make a lot of goods that are relevant for them to import. And they have growth models that are based on export-led with a focus on rich markets like the USA. Vietnam, in particular, has emerged as a quintessential supply chain hub, above all for the manufacture of consumer electronics and garments.

Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia are neighbors and they are all at the top of Trump’s tariff list, but it is important to start with a sense of scale. If we used purchasing power parity measures, which can be deceptive, the Vietnamese economy is more than ten times the size of either Cambodia or Laos.

Vietnam’s population is 102 million. Cambodia’s 17.8 million and Laos is a mere 7.7 million. Vietnam is the major casualty of the tariff shock.

In 2024, Vietnam with a trade surplus of $123.5 billion with the USA came in fourth place behind China: $295.4 billion, European Union: $235.6 billion and Mexico: $171.8 billion. Vietnam is a major player in manufacturing trade.

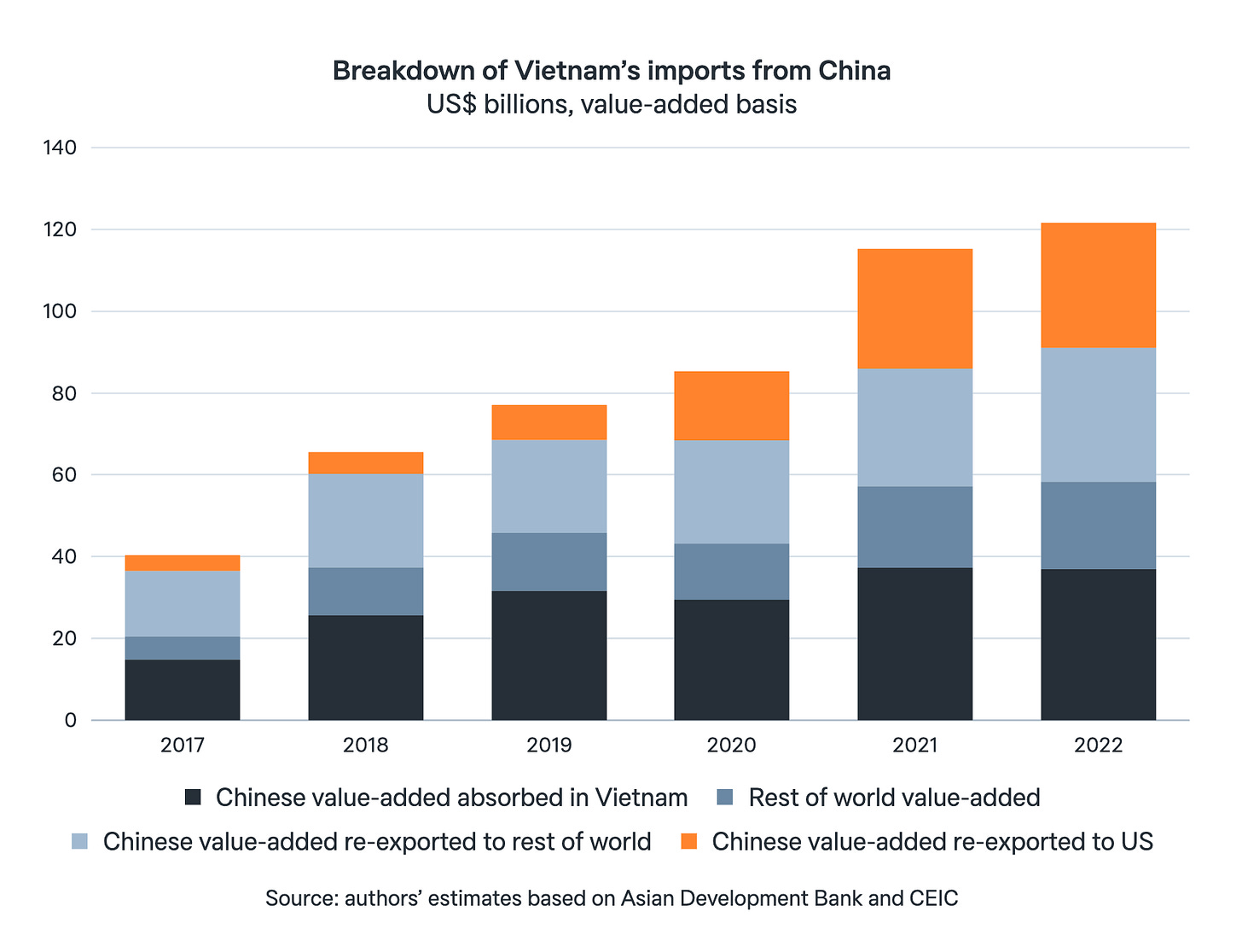

A lot is made of the fact that Vietnam’s exports are not “really” Vietnamese. Vietnam, it is alleged, is acting as a conduit for manufacturing and trade from China. And it is true that there is a striking correlation between Vietnamese imports from China and exports to the USA.

But, as Roland Rajah Ahmed Albayrak writing in the Interpreter point out, to see this as “merely” fiddling the tariff rules, is simplistic. If you break down Vietnam’s imports from China, you see that a more accurate description would be to say that Vietnam is emerging as a key link in globalized supply chains, in which China plays an outsized role.

Around 30% of Vietnam’s imports from China are absorbed by Vietnam itself; after all, Vietnam is a rapidly growing economy with rising incomes. A further 17% of Chinese imports reflect value created in other countries that provide inputs to China’s exports. That leaves just over half of Chinese imports as reflecting Chinese value later re-exported by Vietnam itself. The ADB data does not allow us to directly see how much of this goes into Vietnam’s exports to the United States versus elsewhere. We can, however, make an informed estimate. Crucially, it is not just Vietnam’s exports to America that have boomed in recent years. Exports to the rest of the world have surged by even more, rising US$89 billion since 2018 compared to US$72 billion for exports to the United States. That means a good chunk of Vietnam’s imports from China will have gone into Vietnam’s exports to the rest of the world besides America. If we assume that the Chinese content going into these exports remained proportionally in line with the pre-2018 pattern, whatever remains must reflect increased Chinese content re-exported to the United States. This methodology shows exports to the rest of the world have indeed likely absorbed a great deal of Vietnam’s additional imports from China. But it also confirms a big increase in Chinese content indirectly exported to America. This now accounts for about 25% of Vietnam’s imports from China, a big increase on 8% in 2018. Yet that still leaves around three-quarters of Vietnam’s imports from China that can be explained by factors other than hidden Chinese exports to America.

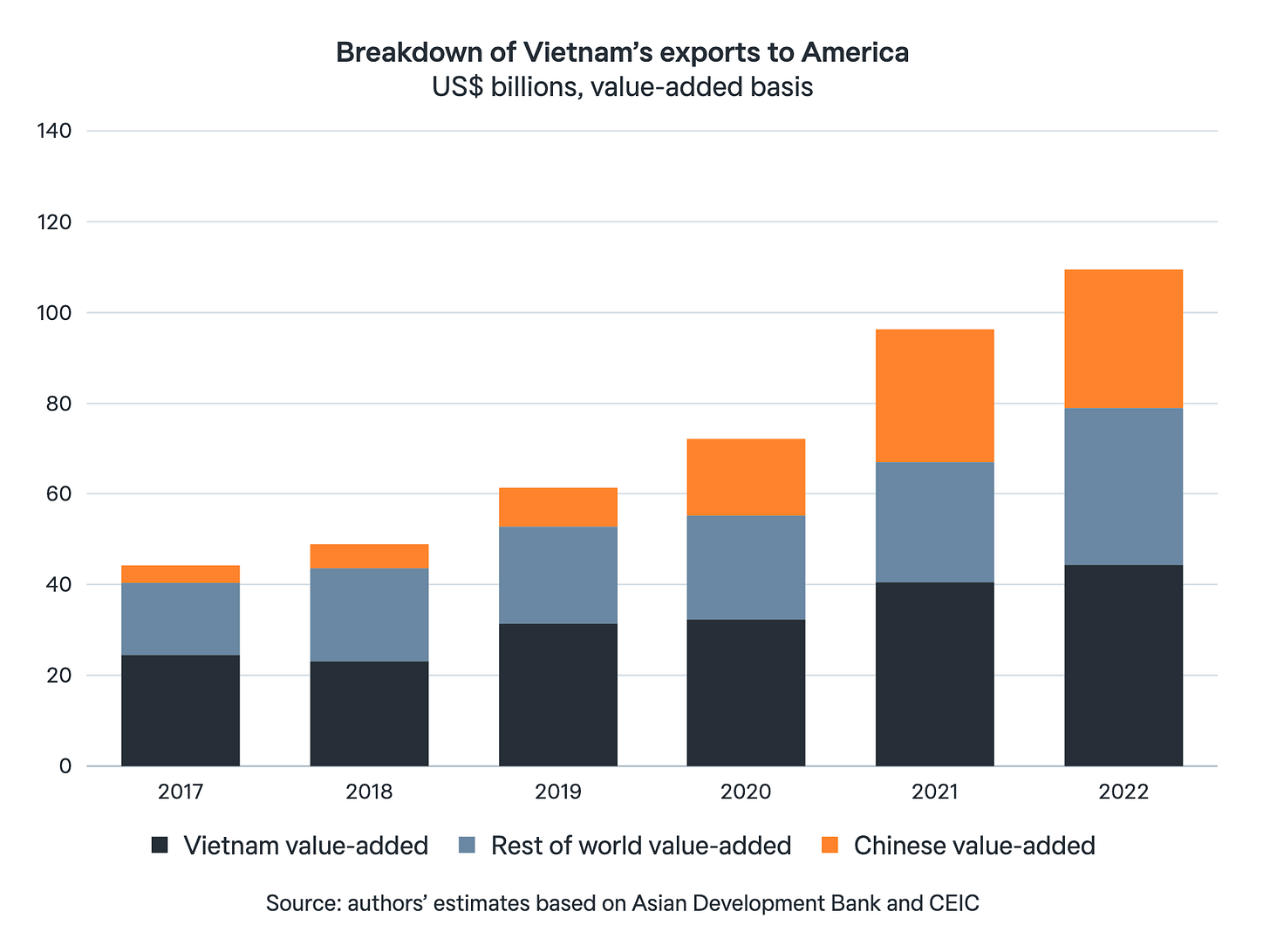

If one focuses not just on imports from China, but on Vietnamese exports then the story becomes even more interesting.

Again, the share of indirect Chinese content has risen substantially, making up 28% of Vietnam’s exports to America in 2022, up from 9% in 2018. However, that leaves the majority (more than 70%) of Vietnam’s exports as reflecting non-China sources – including value produced in Vietnam itself and other countries along the supply chain besides China. It’s also worth noting that Vietnam has benefitted handsomely, with domestically produced value exported to America having risen by more than 90% since 2018 – in contrast to the common handwringing in Vietnam over the limited domestic benefits from its foreign investment driven export sector.

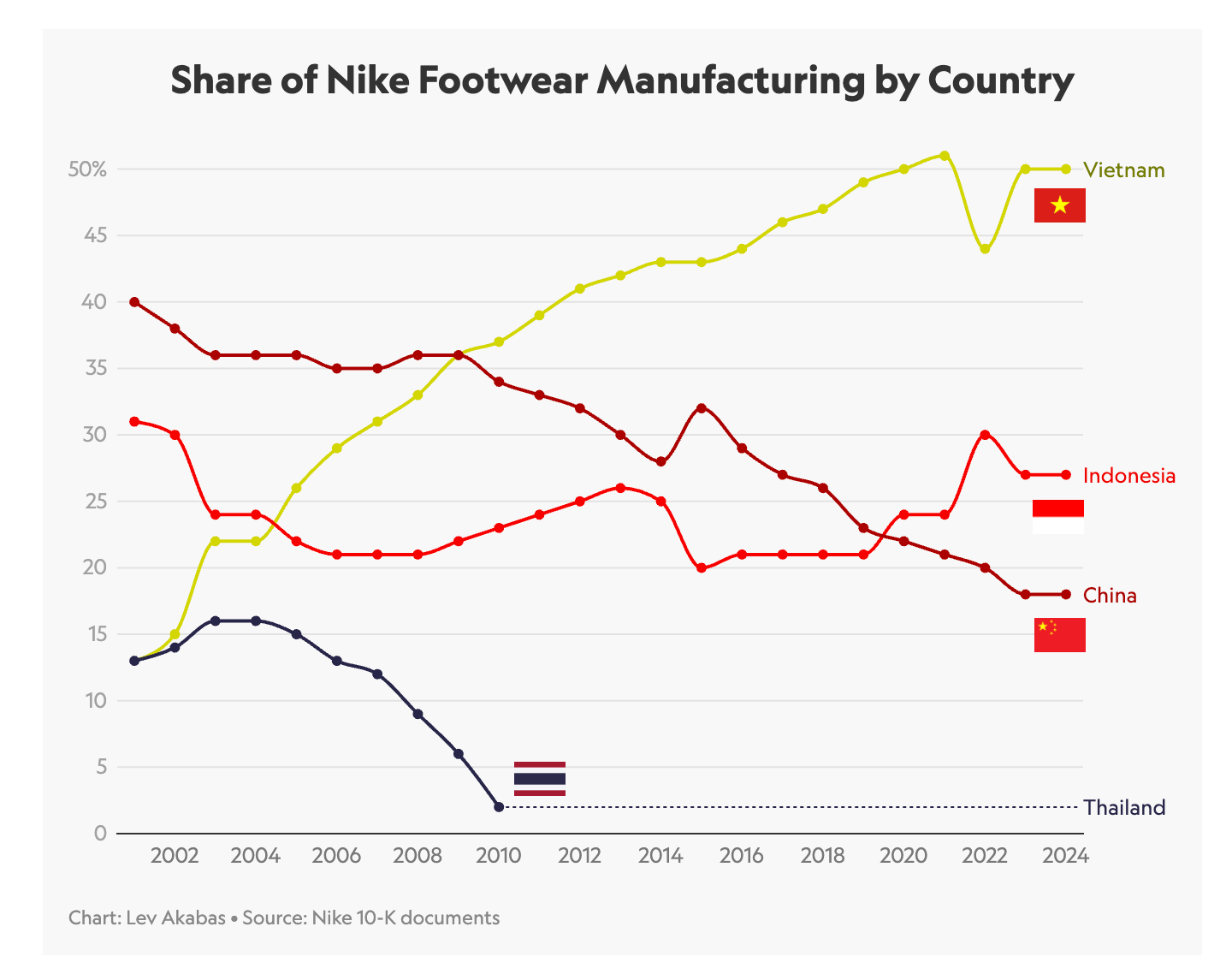

American firms are major players in Vietnam’s emergence as a manufacturing hub. The most dramatic case in point is Nike. Over the last twenty years Nike has shifted production of footwear from China, which once accounted for 40 percent, to Vietnam, which now accounts for fifty percent of its production.

Source: Sportico

Nike is reported to have no less than 155 factories working for it in Vietnam, above all in the South of the country clustered around Ho Chi Minh City.

It is commonly said that Nike employs more than half a million people in Vietnam.

This is a staggering number, so staggering that I was incredulous at first. But it seems to be correct. You can find a complete listing here. Of Nike’s suppliers fourteen have workforces larger than 10,000 workers. The workers are predominantly female.

For sake of comparison, in 2024, General Motors (GM) had roughly 92,000 employees in the U.S., Ford employed about 86,000, and Stellantis had around 95,000 employees in North America.

Nike’s workforce in Vietnam alone would place it just outside the top ten US states in terms of manufacturing workforce. Roughly on a par with North Carolina, or Wisconsin.

So imagine that manufacturing complex being hit by a 46 percent tariff. And imagine that shock being repeated across firm after firm.

As Reuters reports:

The U.S. is Vietnam's largest export market, and in 2021, exports to the U.S. were valued at $142 billion, nearly 30% of the country's GDP. Vietnam's trade surplus with the U.S. exceeded $123 billion last year. Following the announcement from the White House, Vietnam's benchmark stock index had fallen as much as 6.7% as of Thursday afternoon to 1,229.

And, on the other side, “nearly a third of footwear imports in the U.S. came from Vietnam in 2023, the most recent full-year data available, according to the Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America, an industry trade group. In 2023, 26.5% of U.S. furniture imports came from the country, close behind the 29% coming from China, according to data from the Home Furnishings Association, a trade group that lobbies on behalf of home goods retailers.”

Unsurprisingly, the share prices of Nike and other American consumer goods firms plunged on the news.

There is nothing to suggest that the Trump administration actually cares about strategic relationships with major emerging economies, even with nations as large and strategic as Vietnam. The boss hates trade deficits and his team of willing sycophants came up with a formula, however idiotic, that ticked the box. Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia just happened to end up at the top of the list, along with Madagascar and Myanmar. This is not serious trade policy or grand strategy. But its effects will be real. They will be felt by American consumers, investors but above all by millions of working people across the world. And the shock will have long-lasting effects.

As Evan Feigenbaum summarized the fallout on twitter:

“The U.S. is pretty much done strategically in Southeast Asia. The region is filled with pragmatists, who can and do navigate all kinds of crazy stuff from outside powers. But that depends greatly on those players being either principled or strategic – and Washington is now neither. … Over the medium term, bye-bye US influence in Asia. Was already being reshaped faster than the U.S. was adapting. Won’t be the same on the other side of this shit show. The three major pillars - demand driver and open market, standard setter, and security provider - all eroding.

So what the Trump administration wants (a) Nike to start manufacturing in America or (b) Americans to buy/own fewer sneakers?

Utter madness. Americans don't want to work in shoe factories, they don't want to pay the labour costs of American "middle class" wages input in their shoes and what's the point of just having American robots making them instead? You can already buy proudly US made New Balance shoes... at twice the price!

Assuming that America isn't going to have a Marxist awakening, offshoring non-essential manufacturing and issuing non-existent digital dollars for the goods was a golden scenario.

Is anyone honest about what these tariffs are actually going to achieve? Because I have seen a lot of discourse about "enrichment" but less about that enrichment taking the form of fewer material goods...

"The boss hates trade deficits and his team of willing sycophants came up with a formula, however idiotic, that ticked the box" writes Tooze