Chartbook #36 After Afghanistan: No Post-American world

The spending plans of America's soldiers analyzed.

The images from Afghan of American retreat sent shock waves around the world.

They sparked anxious talk of a post-American world.

As I argue in a New Statesman long read, a very different picture emerges if you look at the broader stance of the Pentagon.

What the budgets of the world’s largest military superpower tell us is not only that America’s defense effort is running at a historically high levels, but that its priorities are shifting towards high-tech weaponry for the deployment of military force at a planetary scale.

Before getting into the data, a brief word about Chartbook.

******

I enjoy putting Chartbook together. I hope you find it interesting. I know that Chartbook is read by folks in many walks of life, all over the world. I am delighted that it goes out free to many readers.

But, assembling all this material takes a lot of work. So, if you appreciate the Chartbook content and can afford to chip-in, please consider signing up for one of the paying subscriptions. You will be supporting the mission, earning great karma and some goodies too.

There are three options:

The annual subscription: $50 annually

The standard monthly subscription: $5 monthly - which gives you a bit more flexibility.

Founders club: $120 annually (or another amount at your discretion) - for those who really love Chartbook Newsletter, or read it in a professional setting in which you regularly pay for subscriptions.

As a thank you, paying subscribers receive regular emails with links to some of the most interesting, intriguing and unusual material I come across, around the web. Check out Top Links #5 here.

**********

Since the Pentagon’s budget ebbs and flows, historical perspective is helpful. After the wind down of the 1990s, US military spending was driven to new heights by the Global War on Terror. Much of that spending was on on-going operations and on the Army which was fighting the war on the ground. Overall spending peaked in 2010 at $840 billion.

As the operations in Afghanistan and Iraq were wound down and the deadlock between Obama and the Republican Congress imposed budget caps, overall DoD spending fell to $629 in 2015.

The latest increase began under Trump as the Pentagon's budget was pushed back to over $700 billion. Whilst spending on personnel and operations continues to decline, procurement and R&D spending have risen 30 percent from their recent lows.

So far, the Biden administration shows no appetite to reverse the direction of Trump’s defense policy. The request for National Defense in 2022 is $752 billion (of which $715 billion is DoD).

The Pentagon and the US military-industrial complex are a giant moloch, driven by many interests that do not map in any simple way onto the visions of military planners. But, nevertheless, in the spending patterns we can see a shift towards the priority of high-tech, great power confrontation with China. The momentum is not with the army but the air force, the new Space Force and the navy. R&D spending is gigantic.

**********

To get a sense of the scale of the ambition, the US navy is a good place to look.

In an era of counterinsurgency wars and American global dominance, the navy lost priority. The number of operational vessels fell to a low in the 270s. The new focus on confrontation with China and the ambition of the Trump administration has kicked naval planning into a new high gear. Reading and writing about it you can’t help feeling transported back to 1900s. Not for nothing the US navy was the incubator for American geopolitical thinking.

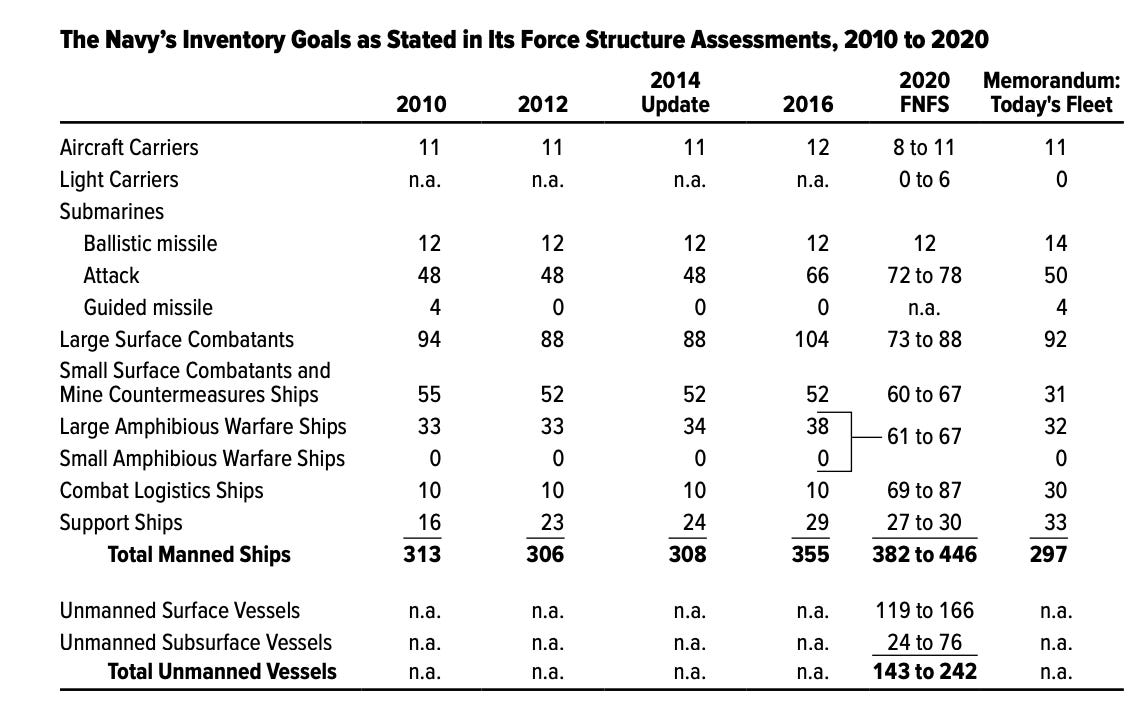

Initially, the Trump administration limited itself to endorsing the Navy’s 2016 force structure assessment that proposed growing the fleet to 355 ships. This target was given the force of law by Congress.

But in the last days of the Trump administration in December 2020, Secretary Esper took the unusual step of releasing a detailed new shipbuilding plan - BattleForce 2045 - that called for 403 crewed ships and 143 uncrewed ships by FY 2045.

Source: CBO

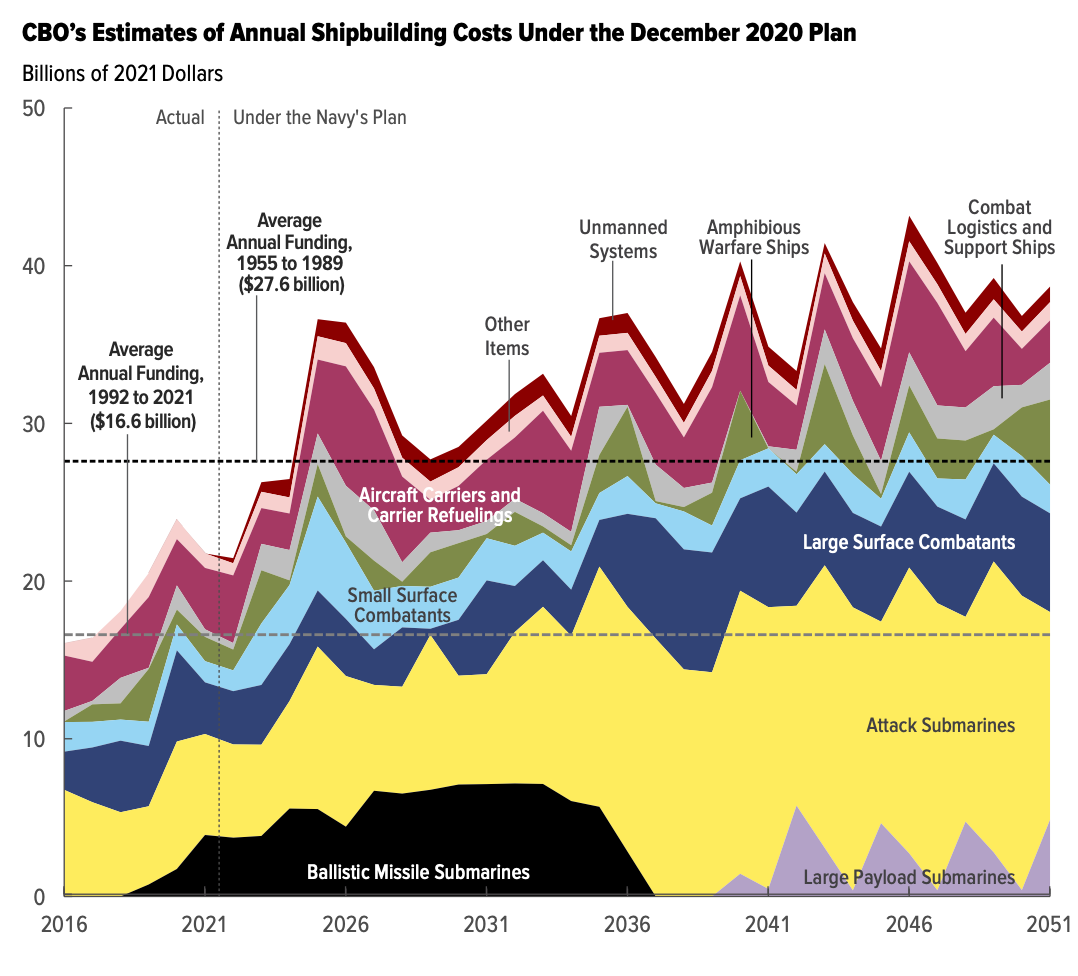

The scale of this proposed spending is huge. The heavy focus on attack submarines signals aggressive maritime intent.

As the Congressional Budget Office remarked in rather stunned tones: “In CBO’s estimation, over the next 30 years, the Navy would spend a total of a little more than $1.0 trillion (in 2021 dollars) building the ships and unmanned systems in its December 2020 plan—an average of $34.1 billion per year. That amount of funding, each year for 30 years, would be unprecedented since World War II. Half of the funding would be for submarines, about one third would be for aircraft carriers and surface combatants, and the remainder would go toward amphibious ships, combat logistics and support ships, and other items.”

Source: CBO

“The Navy’s annual shipbuilding plan would cost more than double what has been appropriated over the past 30 years and 24 percent more than annual appropriations during the Cold War. In the 2040s, funding for submarines alone would exceed average overall funding from 1992 to 2021.”

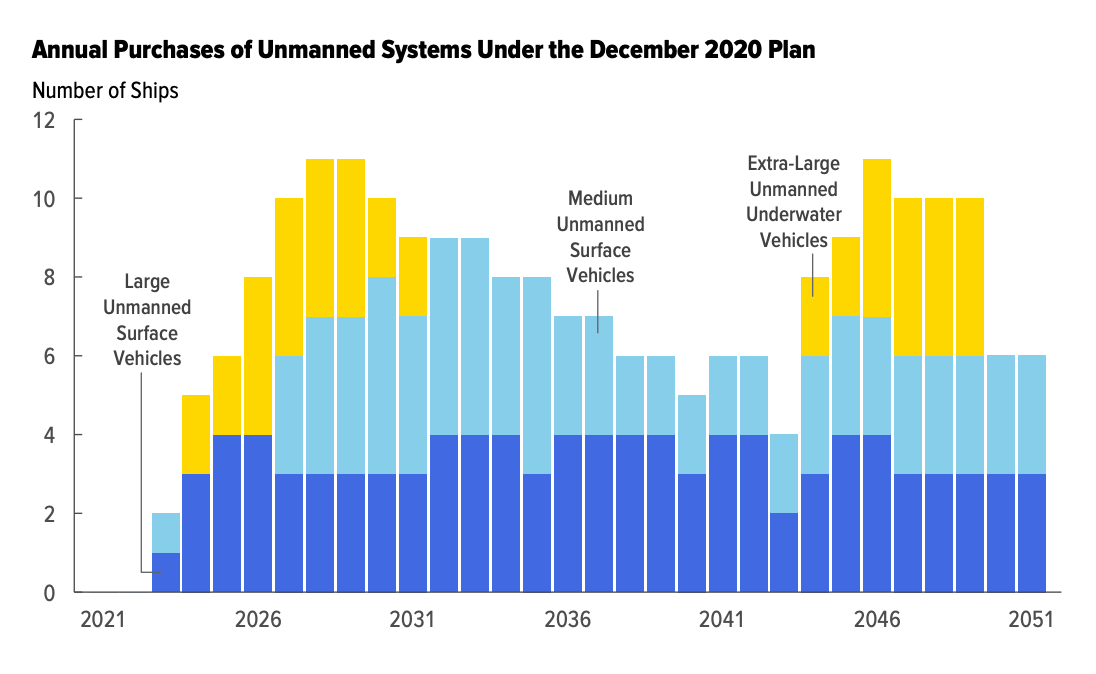

The great technological innovation contained in the Trump-era naval planning is the provision for a large fleet of unmanned vessels. The plan provides for between 119 and 166 unmanned medium surface vehicles (MUSVs) and large surface vehicles (LUSVs) and 24-76 extra-large unmanned undersea vehicles (XLUUVs), for a total of between 143 and 242 systems. As the CBO explains: “The LUSVs would operate in conjunction with other ships, carrying offensive and defensive missiles that manned ships could employ as needed. MUSVs would serve as sensor or command and control platforms, providing information about opponents to other ships in the Navy’s fleet. Although the Navy’s plan is less specific with respect to XLUUVs, they could carry a variety of payloads to support naval operations. The Navy is still developing its concepts of operations for unmanned systems, which increases the risk for both cost growth and delays in their construction and operations.”

In other words, this is a high-tech, futuristic stuff. They are going to have a lot of it. But they don’t know what it is going to do yet.

What might an “extra-large unmanned undersea vehicle” look like? The ORCA XLUUVs that is currently being developed by Boeing and Lockheed are not “extra-large” by the standards of aircraft carriers. They look like overgrown torpedos. The contract value runs into hundreds of millions, not billions of dollars.

Source: Naval Technology

As the CBO notes: “Although the plan calls for building a significant number of unmanned systems, they represent a small fraction of the overall costs of the plan—an average of about $1.2 billion per year, or 4 percent of all shipbuilding costs.” For sake of comparison a single Ford-class aircraft carrier costs $ 12 billion. So, if an Orca, priced at a few tens of million dollars, can sink an aircraft carrier costing billions ….

How much of this will ever be realized remains unclear. According to analysts at CSIS, the aim of Esper’s maneuver may simply have been to “set a new baseline by which the new administration’s shipbuilding plans would be compared.”

The naval planners of the Biden administration are trying to sort out the mess left by their predecessors. Guestimates as to the final target for the fleet lie between the 320s and the 390s. But the basic focus of the Esper plan is likely to remain: submarines, new classes of smaller vessels, uncrewed ships.

One complicating factor is that the navy does not necessarily agree with the priorities of the DoD. In particular, the admirals don’t want a fleet of small aircraft carriers for launching F35s. Congress for its part is passionately attached to large shipbuilding goals and a minimum carrier fleet of 11 vessels. It is quite likely that advanced missile technology and the development of those cheap unmanned vessels will render the entire plan moot.

But there is no doubting the ambition. The withdrawal from Afghanistan in no way signals a retreat from global ambition.

*******

The navy is only one part of the overall budget. Juggling the different components is a vastly complex business. Relating them to actual strategy even more so.

As think tankers at CSIS point out: “It has been about 15 years since DoD explained, even roughly, how it calculated the force levels that it was proposing. The Trump administration was typical. Its 2018 National Defense Strategy sought to “defeat aggression by a major power, deter opportunistic aggression elsewhere, and disrupt imminent terrorist and WMD threats” while defending the homeland and maintaining nuclear deterrence. That required 58 total Army brigade combat teams, 355 Navy ships, about 1,200 Air Force aircraft, and a Marine Corps of 185,000 personnel. There was no description about how the administration determined these very specific force levels from the very general description of strategic goals that it was proposing. This was not unusual. The Quadrennial Defense Reviews of 2014 and 2010 had the same lack of connection.”

In other words, America’s grand strategists formulate goals, the Pentagon draws up lists of things it wants, those have huge costs but it is unclear how each of these decisions relates to the other.

To address this issue, a consortium consisting of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the American Enterprise Institute (yup), and War on the Rocks (the military news and opinion website), have “collaborated to address a shared concern: a lack of understanding about how defense strategy and security objectives are translated into concrete budget choices … The Joe Biden administration’s leaders have asserted that they view China as the “pacing threat” for the Defense Department. Yet how strategic priorities are translated into specific programs in the budget remains largely vague and imprecise. The Defense Futures Simulator will change that, making the process of aligning strategy and resources more accessible, transparent, and engaging.”

They are not the only group to offer you the chance to play grand strategist. The Congressional Budget Office also offers an “Interactive Force Structure Tool”.

Unfortunately, the CBO tool does not cover procurement costs, only operational and maintenance costs. But, with some back of the envelope calculations it can be augmented to provide a full overview of cost.

Last week, noted US security expert Barry R. Posen used the CBO’s force structure tool to devise his own US strategy that would involve stripping America’s commitment to NATO to the bare bones of the strategic nuclear deterrent. This would enable a reduction of 14 US army maneuver brigades, 315,000 personnel, two dozen squadrons of tactical air and littoral combat ships for a total saving of about $78 billion.

A Posenesque strategy would have dramatic implications for European defense. Europeans would have to step up to a considerable degree. It would no doubt produce howls of protests from Atlanticists and be seen as further evidence of “American retreat”. But, it would in fact have no significant impact on America’s strategic nuclear weaponry, its high seas fleet or its air force.

This is one of the insights that emerges from looking into the Pentagon budget. Personnel are very expensive and are getting more so. The Army, as opposed to the navy and airforce, employs a lot of people and that makes it exorbitantly expensive to maintain and operate. To maintain just one Armored Brigade Combat Team complete with National Guard component - numbering 30,000 men and women - at operational readiness, costs c. $ 4.1 billion per annum. That is the same as maintaining and operating America’s entire ICBM nuclear submarine fleet or the eight Minuteman III missile squadrons that provide the first line ground-based nuclear deterrent. Of course, developing and procuring the ultra high-tech submarines and missiles is a different matter.

This distinction between development, capital procurement, operational costs and personnel makes it imperative to break down any spending figures into their different components. As calculations like Posen’s suggest, the US could easily downsize its ground forces and tactical air component, saving tens of billions, whilst substantially increasing its throw weight, its global reach and its high-tech advantage.

********

With this in mind, what is perhaps most dramatic about America’s giant defense budgets is their R&D component. Right now it runs to over $100 billion and makes up 14.6% of overall spending.

The overall DoD allocation to “RDT&E” can be somewhat misleading since it includes a large element for testing as opposed to R&D proper. The American Association for the Advancement of Science compiles detailed figures for different types of government research funding. It credits $73 billion to the military account in 2020, below the all-time high reached in 2010, but sharply up from $53.58 billion in 2015. Spending on military R&D matches all Federal government spending on civilian R&D. It runs at twice what the Federal government spends on health and twenty times the Federal government’s spending on energy research.

In global competition, the scale of America’s military R&D puts it in a league of its own.

In a recent article Gholz and Sapolsky argue that America’s R&D advantage in military technology is so large that it is hard to see its losing its preeminence any time soon. I would not like to make a wager on that one way or another. But if the question is whether or not the shift in posture in Afghanistan implies a more general retreat from global power the answer is clearly no. The intention is the reverse. The US is seriously gearing up for a new era of global military competition. Given the focus on high-tech competition that will have broad implications for economic and industrial policy both in the US and across its alliance network.

In next week’s Chartbook Newsletter I am going to be following up another theme in the New Statesman article, the "second offset” and the moment when the US Army learned to stop worrying and to love the Wehrmacht.

If you enjoy Chartbook, why not share it with a friend.