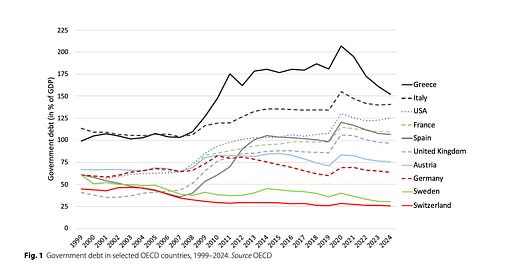

For years many of us have been campaigning for a fundamental change in German fiscal policy. Within the club of OECD states its position has been increasingly anomalous.

Source: Brändle & Elsener (2024)

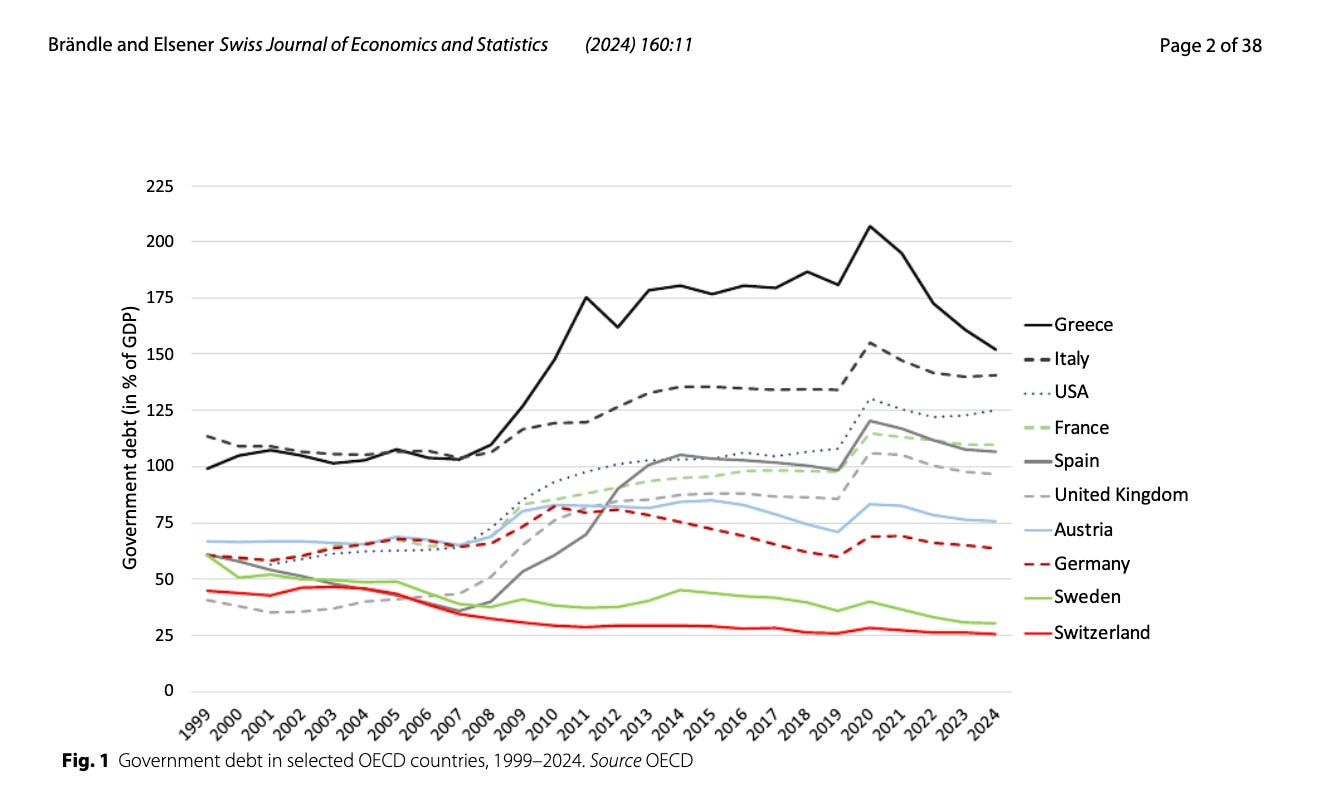

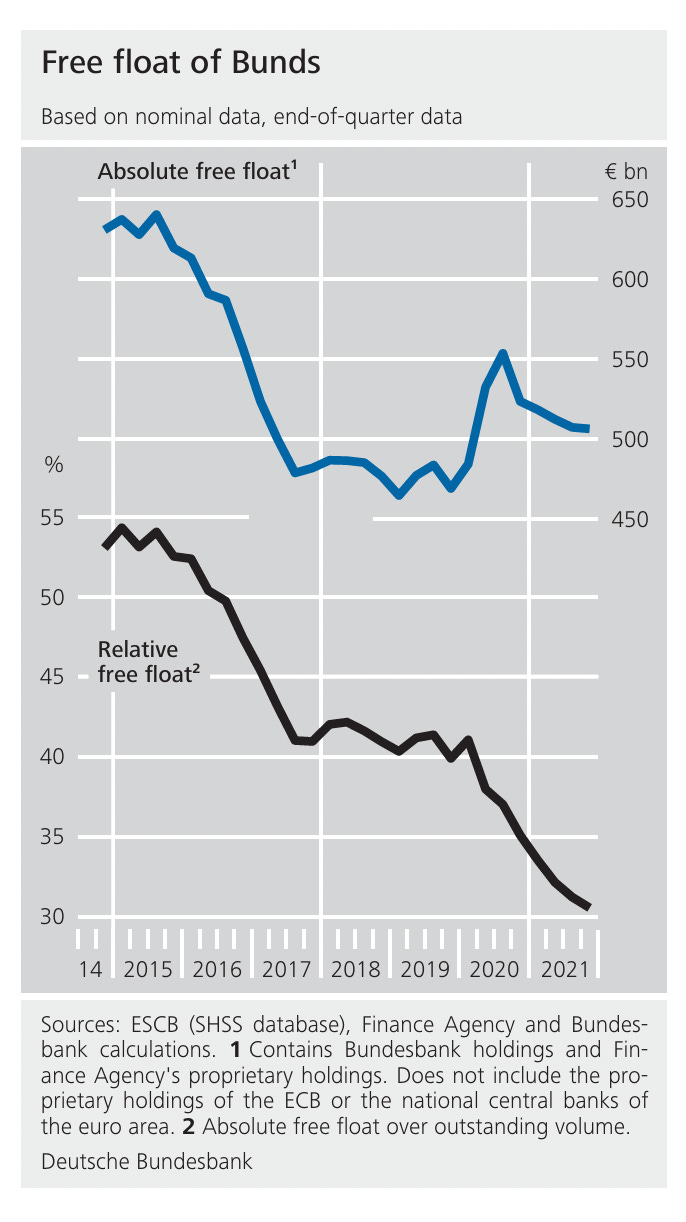

Germany has by far the lowest debt to gdp ratio of any large economy. Unsurprisingly fiscal restraint at this level has gone hand in hand with low levels of public investment and a general macroeconomic. imbalance that leaves Germany heavily dependent on foreign demand. Meanwhile German public debts available for public purchase - “free float” - became increasingly scarce, a squeeze compounded by the asset purchases of the ECB.

Source: Bundesbank

As the Bundesbank itself remarked: “The reduced volume of assets available for trading increasingly led to periods of scarcity that negatively affected market conditions.” Meanwhile beyond the churn of the financial markets, German savers faced negative interest rates.

Germany has, therefore, become a poster child for an economy operating with a dysfunctionally low level of public debt finance.

It is, therefore, good news that with the exception of the liberal FDP, who will no longer be in the Bundestag, and the objectionable AfD, all major German parties have now come around to the view that the debt brake must be revised. They do not, however, agree how to do this or what purpose justifies the move. And that matters, because amending the constitution requires a two third majority.

The fact that the CDU and SPD have agreed on a relaxing the debt brake in their coalition talks has made the topic not just into German but global financial news. What is surprising, however, is that this is being treated as a done deal when they have not in fact answered the basic question, which is how to assemble a two-thirds majority.

From the point of view of the CDU and SPD there is an obvious tactical logic to talking in terms of politically inevitability. This increases the political pressure on the Greens to go along with their strong arm move (for the details see below). What is more surprising is that international commentators are repeating and amplifying what is in fact an audacious gamble. From the point of view of progressive politics in Germany the CDU-SPD proposal, far from being something to welcome with open arms, in fact presents profound dilemmas. The Greens are faced with a historic choice: whether to go along with the CDU-SPD maneuver whilst sacrificing the key points of their own agenda, or whether to dig in their heels and to force the new government under Friedrich Merz to negotiate with the new Bundestag on the basis of which his coalition will actually claim its majority.

I started to outline these dilemmas in the last Chartbook. I returned to the problem yesterday on the website of Surplus magazine, the German-language progressive economics platform of which I am one of the publishers. The English version is below.

This week news from Germany shook global finance. It doesn’t take all that much. The markets right now are in a nervous mood over the direction of the Trump administration. But then came the news that the CDU and SPD early in their negotiations over a new coalition had agreed to relax the debt brake for defense spending and to set up a 500 bn Euro fund for infrastructure investment. This is big. Not just for Germany. All told new debt issuance might come to 1 trillion euro.

That is a huge number. But the markets did not respond with the kind of panic we have seen from some German conservatives. On the contrary. The promise of new German debt is extremely welcome. German Bunds are normally in uncomfortably tight supply. Even if Germany borrows 1 trillion over the next ten years that might raise Germany’s debt to gdp ratio from 60 to 85 percent, far below the USA or the Eurozone average. But what 1 trillion in new German debt do mean is that investors will need to be offered slightly higher interest rates. German debts right now have some of the lowest interest rates in the world, displacing investors into other European assets like French, Spanish and Italian bonds. These are slightly riskier but they yield a better return. The sudden availability of high-quality German debt puts pressure on issuers of lower quality debt around Europe. And this effect is heightened by the prospect that a German government under Merz might agree with a Von der Leyen commission in Brussels to issue even more European defense bonds. All of this would be high quality debt. All of it would attract eager investors. There is zero prospect of a European fiscal crisis. It is just that issuing such a large volume of bonds will cause the balance between borrowers and lenders to shift. An increased supply of very high quality debt will push prices down and when that happens to the price of bonds, the effective rate of interest, the yield (rendite) goes up and this will lead to a reallocation of trillions of dollars in global portfolios. This means lots of business for the busy men and women who manage really large portfolios of assets.

All in all the sudden realization on the part of the CDU and SPD, the joint authors of the debt brake back in 2009, that Germany should be borrowing to invest, is overdue cause for celebration. Finally, Germany is showing signs that it may lead Europe in providing an adequate answer to the challenges of the moment: how to generate sustainable growth and put Europe’s defense on a footing that does not involve humiliating and dangerous reliance on the USA.

Many of us have been campaigning for years for the repeal of the debt brake and for an expansive European investment policy, led by Germany. This now finally seems on the horizon.

But, as is always the case when economic policy is formulated in general macroeconomic terms, the politics only starts with the rough outlines of fiscal and monetary policy. It is good that these are now set in an expansive direction and Germany’s political class is getting over its perverse hangups about debt. But it is clear that this will then require imaginative thinking about the three things: First, the side effects of running the economy hot. Then, there are fundamental questions about the priorities of the spending. Finally, there are even more glaring and immediate questions about the democratic legitimation of this turning point in the economic policy history of the Federal Republic.

The first question, that of structural change should be faced with a progressive vision of change. The second, that of priorities, should be met with a clear rejection of the current CDU-SPD plan and a demand for other priorities. The third dimension, the party politics of the proposal, should in fact be a cause for scandal. It is astonishing that the CDU-SPD proposal is even being considered.

The German economy right now can do with the extra demand. Real wages have fallen since COVID. Industrial production has slumped. There is a risk of prolonged recession. But it is also true that German society reacts sensitively to price shocks. And running the economy hot with a large flow of new investment will produce price pressure. This has to be managed politically, not rejected.

Germany needs structural change. Structural change is regionally uneven. The pressure on the cost of living in growth hot spots will be pronounced. At every level, in neighborhoods, cities, regions and at the national level there will need to be a debate about how to handle these stresses. This should be welcomed by progressives as a chance to articulate policy and to openly discuss the inherently political nature of economic relations.

Overall, however, the basic point is that German society will have to face the question: are we ready for more rapid growth and for actual structural change? You cannot promise to invest a trillion euros and also promise that everything will remain the same (alles beim alten bleibt).

If the money is actually spent, things will change willy-nilly. The question is who steers that change and in what direction. What will be new, however, is not just the pace of change, but the overall envelope. Compared to austerity under more rapid growth conditions the trade-offs remain trade-offs, but they are cushioned by overall growth. There will be gentrification and displacement effects, for instance. But with the new infrastructure fund we can now also demand that there are genuine social housing options available for those who can no longer afford to live in the growth hot spots. It was this trade-off that made the extraordinarily dramatic structural change of the years of the economic miracle (Wirtschaftswunder) bearable. If we are serious about transformative investment, and progressive economic policy demands this, then we have to prepare for a new era of mobility and change. Getting the politics right will consist in asking who moves, who changes and under what conditions.

Spending the money will shape an economy and society marked by more rapid growth. How the money is spent will shape Germany’s future. What is clear from the existing CDU-SPD outline is that it gives special status, though in different ways, to defense and infrastructure. What is also clear is that it downgrades other priorities, notably the energy transition and the climate crisis. Social policy, meanwhile, is consigned to the rump of the regular budget, which will be subject to continuous pressure from the debt service accumulating on the side of defense and infrastructure. This allocation of priorities should be profoundly problematic for progressive politics.

There is no contradiction in saying that one favors the end of the debt brake and a major investment push and at the same time to challenge a program as lop-sided and transparently partisan as the one that the CDU-SPD are proposing. It is being dressed up as the obvious, technocratic answer to national priorities. It clearly does reflect the priorities of expert group that helped to shape it and the two parties that have signed up for it. But there is no such thing as an unpolitical definition of national interest and this extends to areas like national security. Faced with the CDU-SPD proposal one has to ask, is Russia really a more serious threat to the security of Germans than the global climate crisis or the fact that an alarmingly large share of children in Germany grow up in poverty? These are the debatable questions that are buried in the technical structure of the CDU-SPD proposal.

Indeed, if there is one thing that is clear about the CDU-SPD proposal it is its party-political logic. Since the FDP began to dig in its heels over budgetary policy in 2023 it has been clear that the only sustainable coalition to govern the Federal Republic is a Kenya coalition. And yet for Merz and Soeder’s CDU/CSU this is a horror which, with their vicious attacks on the Greens, they have done everything possible to forestall. They were spared the nightmare of having to govern with Kenya by the few thousand votes by which BSW fell short of 5 percent on February 23rd. On the other hand that same election result means that to pass a debt brake reform in the new Bundestag, which must convene by March 25th, they would need not only the Greens but die Linke too. If there is a prospect even more horrifying for Merz and Soeder than Kenya, it is this. So now they choose the lesser evil of trying to bounce a constitutional change through the lame duck Bundestag in record time, whilst presuming that they can count on the support of the Greens who will not, however, be part of the new government. This from Merz’s point of view would be the best of all worlds, an enabling measure passed by Kenya, without the political risk of actually governing with Kenya.

Both on general democratic principle and specifically from a progressive point of view it is entirely objectionable. The idea of passing a constitutional change of such importance at the behest of a putative new government, in a lame duck parliament whose balance is quite unlike the new Bundestag should be a cause for scandal. It would mean that the change goes through on a technicality and is deprived of legitimacy from the start. The fact that the maneuver is designed to strong arm the Greens and exclude Die Linke so as to prioritize defense over environment and social policy should make it further unacceptable to anyone in the progressive camp. The fact that the SPD is promoting this in coalition with Merz and Söder, marks the nadir of a shocking phase in the party’s history.

Overcoming the debt brake is a historical necessity. If the CDU-SPD deal does anything, it makes clear that even Merz and Söder know this. To respond to genuine historical challenges, it is long overdue that German democracy should free itself from self-imposed immaturity (selbstverschuldete unmuendigkeit). But this should not start by subverting democracy through a last minute back door maneuver that does an end run around the outcome of the election held as recently as February 23 in which a historic share of the German electorate went to the polls. What is required is a general revision of the debt brake on the basis of the majority in the new Bundestag which is clearly available if the CDU and SPD are willing to compromise rather than to ramrod their priorities through the technocratic back door.

Ultimately the question now hangs on the Greens. It is a historic decision. To accept the CDU-SPD “offer” as it stands would be a major political mistake. It is hard to see what could possibly justify such a subversion of due democratic process. Certainly talk of the Trump emergency or Putin threat are not adequate to justify such a maneuver. The climate crisis might. The very least that would be required, therefore, is a fundamental reorientation of the CDU-SPD package in the order of hundreds of billions of euros, towards the priorities of the climate crisis. The CDU/CSU should be required to abandon their aim to rollback climate legislation and be forced to lay out a social safety net for the eventual introduction of the ETS2. De facto this would amount to a Kenya coalition agreement. If this cannot be done on the hair raising timeline apparently envisioned by the CDU-SPD negotiators, so be it. Nothing less should be the price that the Greens exact.

Will this cause further shifts in global bond markets? Quite likely. It may come as a surprise to bond jockeys that German democracy is actually complicated. They may prefer otherwise. But it is a lesson that it would be good to remind the portfolio managers of. They are all too eager for the new German debt. A little wait will not dampen their appetite.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates.

Great article, thank you Adam. One thing that also might be worth mentioning is the various legal challenges being made against this scandalous move to use the old bundestag to rail through a profoundly contrversial action, the most interesting of which seems to be a requirement of the consitution that a two week period is requied between the frst and second readings of a new bill. Currently the CDU/SPD programme foresees a 5 day period only (13 - 15 March).

In some ways, increased investment in infrastructure will green the economy indirectly, as today's infrastructure technology is (much) greener than whatever is replaced (I assume infrastructure here means housing, transportation, and energy production and distribution). Also, increased defence spending will mitigate the electrification of the car industry, as much of the old supply chain can be retooled for defence purposes, smoothing the transition. But yes, there needs to be a green aspect of the investment (energy security through investments in heat pumps, renewable energy and so on). The Greens would be wise to demand subsidies to sweeten regulatory and security pressures towards decarbonisation.