The three-episode history of the eurodollar presented by Lev Menand and Josh Younger on Odd Lots is one of the best podcasts of recent times.

Episode One is here:

Episode 2 was my favorite. A masterpiece of explanation and story-telling. But it pays to listen to all three episodes sequentially.

Eurodollars like other monetary systems are bootstrapped into existence.

They originate in the willingness of businesses around the world to take payment for good and services in dollars, the national currency of the United States. If those dollars are exchanged for the local currency of the exporter, or if they are deposited in the US banking system, then the boundaries of national currency systems remain unblurred. Eurodollars - offshore dollars - are created when those businesses choose to deposit their dollars with banks outside the US - whether American, European or otherwise. Those banks look for investment opportunities to enable them to earn a return in exchange for the liability involved in holding a deposit. That means they have to find someone who wants to borrow dollars outside the United States. Offshore dollar deposits generate offshore dollar lending. A world of dollar-denominated business thus emerges outside the territory of the United States and beyond the immediate reach of US monetary or financial authorities. The system works because dollars can be widely used in international trade and finance so there is no immediate reason to swap dollar earnings into home currency. At the same time, the availability of eurodollar facilities, makes the dollar useful for more purposes including lending and borrowing between non-Americans and businesses not immediately connected with the USA. When we speak about the hegemony of the dollar we are in large part talking about the tentacular extension of the eurodollar system.

Eurodollars are called eurodollars not because they have anything to do with the EU or the euro, but because the telex handle of one of the first bank to be involved in the business in 1950s was “Eurobank”. In due course “Eurobank dollars” became simply “eurodollars”. Today the eurodollar system is gigantic. Here is a recent summary for the Atlanta Fed by Robert N. McCauley, of Boston University and the University of Oxford, formerly of the BIS and the NY Fed.

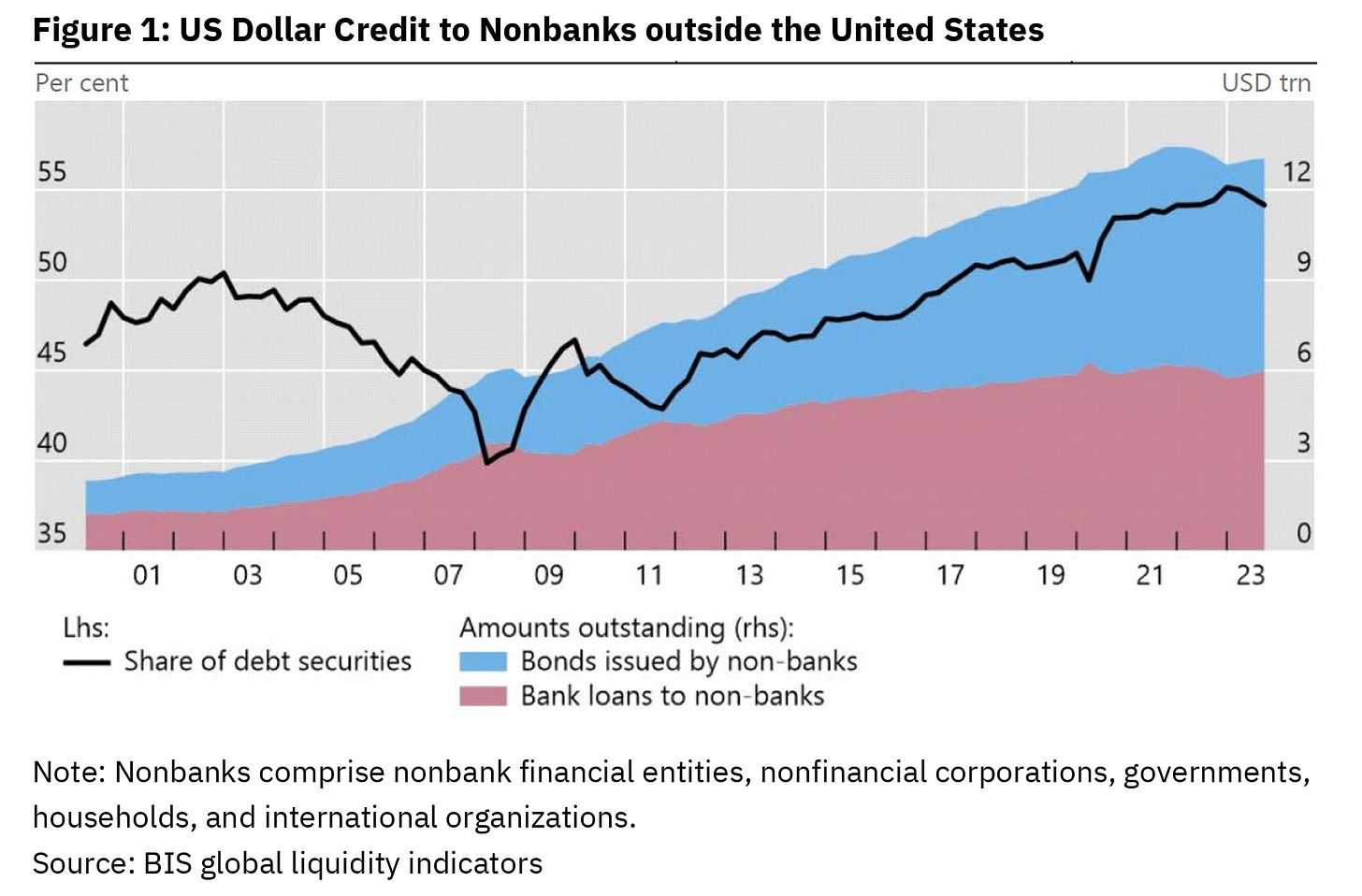

The dollar’s global role requires that non-US residents pay trillions of dollars every day. Nonbanks outside the United States must make repayments on a $13 trillion stock of dollar debt, mostly held abroad (figure 1).

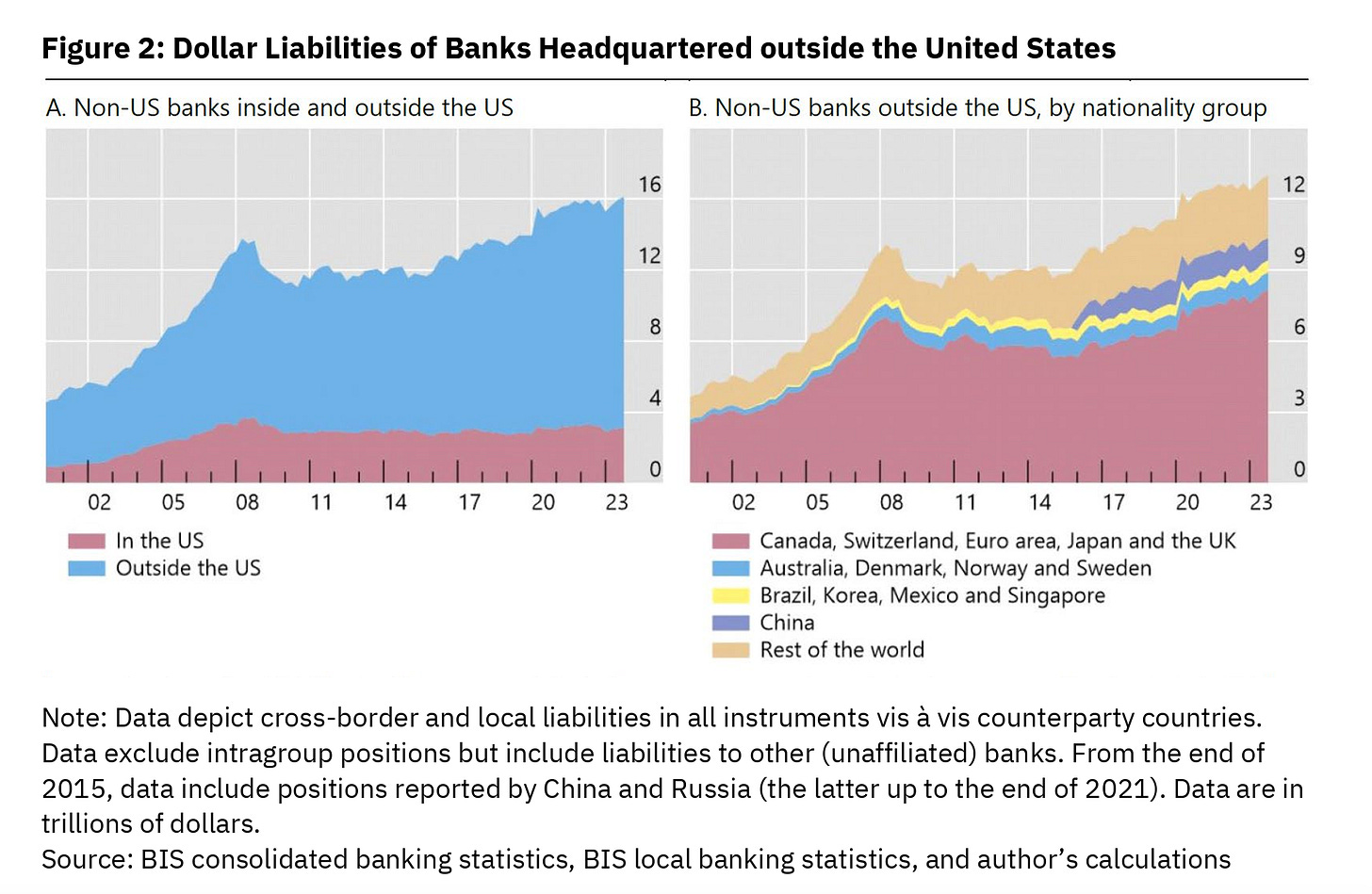

After the Great Financial Crisis, dollar bonds outstanding grew faster than dollar bank loans and now represent more than half of this stock of offshore dollar debt (Hardy and von Peter 2023). Figure 1: US Dollar Credit to Nonbanks outside the United States Note: Nonbanks comprise nonbank financial entities, nonfinancial corporations, governments, households, and international organizations. Source: BIS global liquidity indicators Banks headquartered outside the United States need to roll over maturing dollar obligations on a $16 trillion stock of deposits and bonds (figure 2, left-hand panel).1

About $3 trillion of these obligations are booked at branches and subsidiaries in the United States. In principle, these foreign bank affiliates in the United States have access to dollar funding at time of need from the Fed’s discount window. But banks headquartered outside the United States have another $13 trillion in dollar obligations booked outside the United States. The Fed’s discount window does not provide a direct backstop to these liabilities. 1Up from $13 trillion at end-2019 (Aldasoro et al. 2020). Figure 1 shows debt by residency while figure 2 shows it by nationality. See McGuire et al. (2024). 3 Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Policy Hub • No. 2024-2 Figure 2: Dollar Liabilities of Banks Headquartered outside the United States Note: Data depict cross-border and local liabilities in all instruments vis à vis counterparty countries. Data exclude intragroup positions but include liabilities to other (unaffiliated) banks. From the end of 2015, data include positions reported by China and Russia (the latter up to the end of 2021). Data are in trillions of dollars. Source: BIS consolidated banking statistics, BIS local banking statistics, and author’s calculations On top of these outright debts are large stocks of off-balance sheet obligations to pay dollars arising from foreign exchange (FX) swaps and forwards and longer-term currency swaps. In an FX swap, one counterparty borrows dollars against the collateral of an equivalent amount of another currency. For instance, a Dutch pension fund or a Japanese life insurer may borrow dollars and lend euros or yen in the “spot leg” and later repay the dollars in the “forward leg.” A dollar bond bought with the dollars is thereby hedged back into euro or yen. An investor who seeks to avoid the risk of the dollar must borrow dollars. It deserves emphasis that FX swaps are not some side bet, settled with a one-way payment by the loser to the winner, as in most derivative transactions. No, in a $100 million FX swap, that full amount is borrowed and repaid. These off-balance sheet dollar obligations well exceed the on-balance sheet dollar debts. Nonbanks outside the United States owed an estimated $26 trillion in these forward deals in mid-2022, about double their on-balance sheet dollar liabilities. Non-US banks owed another $39 trillion (Borio et al. 2017, 2022), more than double their on-balance sheet liabilities. The FX swap market is the largest outstanding dollar credit market, but its off-balance sheet nature means that it is often overlooked (unlike dollar borrowing collateralized against securities, namely repo). Dollar FX swaps turned over $3.5 trillion a day in April 2022, mostly at maturities less than a week (BIS 2022). The dollar predominates in this market like no other, 4 Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Policy Hub • No. 2024-2 with the dollar on one side of about 90 percent of all FX swaps. And US banks occupy an outsized and pivotal position in this funding market. European banks swapping euros into yen transact through dollars with US banks, as do Japanese banks swapping yen into euros (Kloks et al. 2023).

So the history of this system matters. How we tell that history is crucial in shaping our understanding of what makes the global financial system tick. The story given by Menand and Younger is fascinating because it blends commercial imperatives, macroeconomics and geopolitics.

As Menand and Younger explain, eurodollar business first developed in the 1950s as a way for exporters who were earning dollars to avoid sanctions by the US authorities. Ironically this was particularly interesting for exporters in Communist countries. The lending side of the business was supported by the fact that European firms were happy to borrow dollars locally for the purpose of trade finance, for instance to pay for raw materials. For US firms it was attractive not to repatriate profits earned in Europe and elsewhere in part because regulations imposed on US interest rates limited the rates that could be paid on dollar deposits in the US. The competition for eurodollar deposits was freer both for banks and depositors. LIBOR was an average measure of the interest rates at which banks in London, the main center of the eurodollar market, lent and borrowed from each other.

At first, the scale of the business was modest. It was, after all, an irregular kind of banking - shadow-banking - which lacked the guarantees and oversight that holding dollars with a US bank in the US would have provided. Banks involved in eurodollar business are not regulated by the US authorities and do not have assured access to the support facilities of the Fed. But, the new market for dollars offered flexibility and the means to conduct business in dollars in Europe, which was then still the second great hub of the postwar world economy. For the City of London it offered a welcome chance to compete with Wall Street even after the dollar replaced sterling as the top currency.

As Menand and Younger go on to argue, eurodollars really took off in the 1960s when they were discovered as a helpful buttress and rampart for the Bretton Woods system.

Under the Bretton Woods system, onshore dollars - dollars held in the US financial system - were claims on America’s holdings of gold. Because this was not a fiat system, onshore dollars were not sufficient to themselves, they were tied to gold at par. One might say that gold was the ultimate “mainland” and greenbacks were themselves “offshore” in relation to the gold reserve held in Fort Knox. Value was conferred on greenbacks, at least by the formal structure of this system, through their “peg” to gold. $35 dollars exchange for an ounce of gold.

In the 1960s the outstanding dollar claims began to overwhelm the gold available to back them. The US authorities regarded the dollar peg of gold as key to the credibility of the Western economies in the Cold War. They were, therefore, looking for ways to manage global claims on America’s limited gold stocks. Keeping dollar business offshore in a self-sustaining eurodollar system was a convenient way to reduce pressure on US gold reserves, the core of the global monetary system.

Fostering the growth of the eurodollar system depended on making it more stable . To build confidence and reduce the temptation to return dollars to the US, Eurodollars needed to be made as dollar-like as possible. So the US financial authorities moved to backstop the eurodollar system with analogues for the kind of support they provided to the domestic financial system. As Menand and Younger explain it, swap lines, offering last resort liquidity in dollars to central banks and banks outside the USA, were first employed in the 1960s, both to support exchange market intervention and, more generally, to support the eurodollar system.

This is a fascinating prelude to the gigantic swap line and liquidity facilities that the Fed would provide to the global dollar system during the financial crisis of 2008. As I showed in Crashed more liquidity was provided by the Fed to non-US banks than to US financial institutions. Some of this was through branches of those banks in the US (onshore). Some of it was provided “offshore”, by way of central bank swap lines. Faced with the market disruption of 2020, the swap lines were again activated and huge interventions were mounted to defend the shadow banking system, onshore and offshore.

Unfortunately, Menand and Younger stop their fascinating narrative with episode 3 in the late 1970s. I wanted episodes 4, 5 and 6.

Craving more recent material, I tuned into one of the next episodes of OddLots. It turned out to be about what crypto wants from the Trump administration.

This was fascinating in its own right. If you want to understand why crypto is actually making serious headway with big money and policy in DC, listen to Austin Campbell, professor at NYU's Stern School of Business and the CEO of stablecoin company WSPN USA. He is a highly plausible advocate. But my ears really pricked up when Joe and Stacey challenged their Campbell with the question: “Ok. Crypto and stablecoin are all very well. But what, really, is the use case? What are these complicated constructions good for?” Campbell’s answer was telling: “Eurodollars. Stablecoin will end up displacing eurodollars.”

Here was the sequel to the Menand & Younger show that I was craving. In fact, my memory was jolted to the brief moment in one of the Menand & Younger conversations in which they discuss the size of the eurodollar market. As their yardstick, as if out of thin air, they plucked the current size of tether, the leading stablecoin. It struck me as odd at the time. But with Campbell’s bold suggestion that stablecoins would soon replace eurodollars the penny dropped.

If eurodollars are offshore deposits and lending in dollars, what are stablecoin? And why might one imagine these systems as overlapping, or one as the replacement for the other?

The answer is that if eurodollars are dollars that circulate offshore, stablecoin are onchain crypto assets that are tethered to the conventional (i.e. offchain) financial system. Since dollars are the main currency of the conventional financial system, stablecoins are, like eurodollars, a kind of hybrid. They are links between the onchain crypto world and the offchain dollar system.

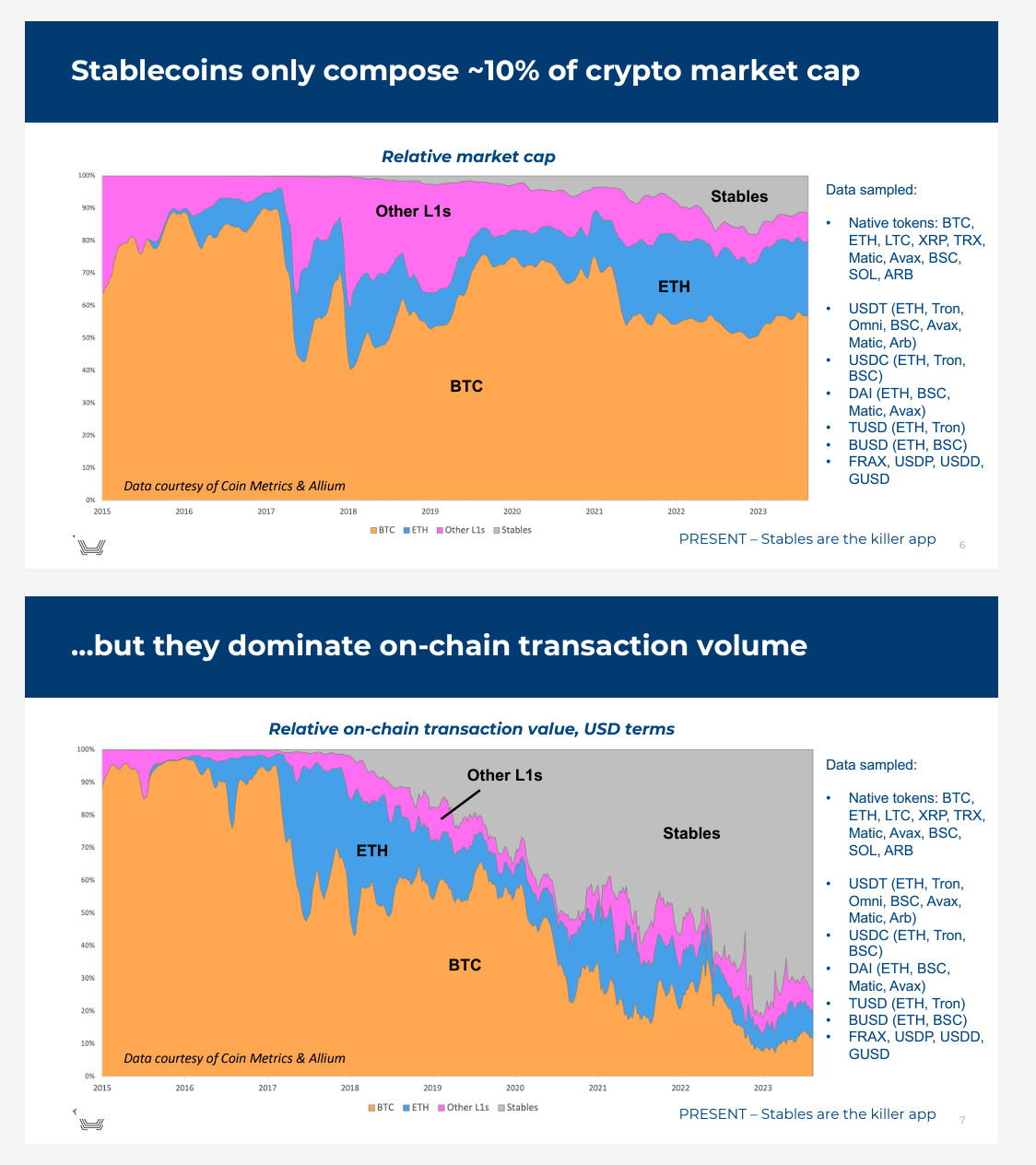

Stablecoines are only a small part of the crypto space by market cap. But their fungibility gives them a dominant role in transactions. In this respect they serve a similar role to eurodollars in global trade finance.

Source: Castle Island

Crucially, like eurodollars, stablecoins promise to exchange for dollars at par, i.e. 1:1. Unlike bitcoin et al, stablecoin offer no upside possibility of appreciation (against the dollar). But there is also (they promise) no risk of depreciation. Their unique selling point is that they are squarely in the crypto world and yet dollar-like.

The crucial question, is the question of parity. What makes Eurodollars, dollar-like is the promise that they exchange 1:1. What preserves parity between eurodollars and the dollar is the entire institutional commitment and history that Menand, Younger and many others have explained. That commitment has been repeatedly tested and it has become clear that the eurodollar system is far, far too big to fail. In other words the promise of parity must not be violated, at least not in dangerous ways over long periods of time. Stablecoin have a much shorter history but the attempts to anchor them at parity use techniques that are familiar from centuries of banking practice. They rely essentially on one to one backing of their stablecoin issuance by dollar deposits, or some kind of fractional reserve cover. This makes them either like a well supported currency board, in which a foreign currency is pegged to the dollar, or like a eurodollar bank.

Given these obvious structural parallels, drawing the analogy between stablecoin and eurodollars is not new.

The first person to make the link may have been Izeblla Kaminska of the FT’s Alphaville blog back in September 2017. Apologies to anyone who got there even earlier.

By August 2021 Niall Ferguson on Bloomberg was arguing that the lesson of the collapse of the Bretton Wood system in 1971 was that the dollar remained strong, so long as the US authorities permitted financial innovation. In the same way as the Western authorities had permitted eurodollar innovation half a century ago, they should now encourage experiments with crypto. Trying to compete with China over central bank digital currencies was a losing bet.

By 2022 smart crypto boosters like Nic Carter were putting together slide decks that spelled out the historic analogy and argued that stablecoin were the future of the dollar system.

One reason that the supporters were as vociferous as they were was that the authorities did not like stablecoin projects. The Financial Stability Board and the IMF have been keeping a wary eye on stablecoins. In terms of fin-tech innovations the authorities much prefer central bank digital currencies, which are anathema to the crypto crowd.

In 2024 Lev Menand himself wrote a report for the Roosevelt Institute, arguing for a comprehensive reworking of the monetary system in the public interest. He both acknowledged the analogy and called for regulation.

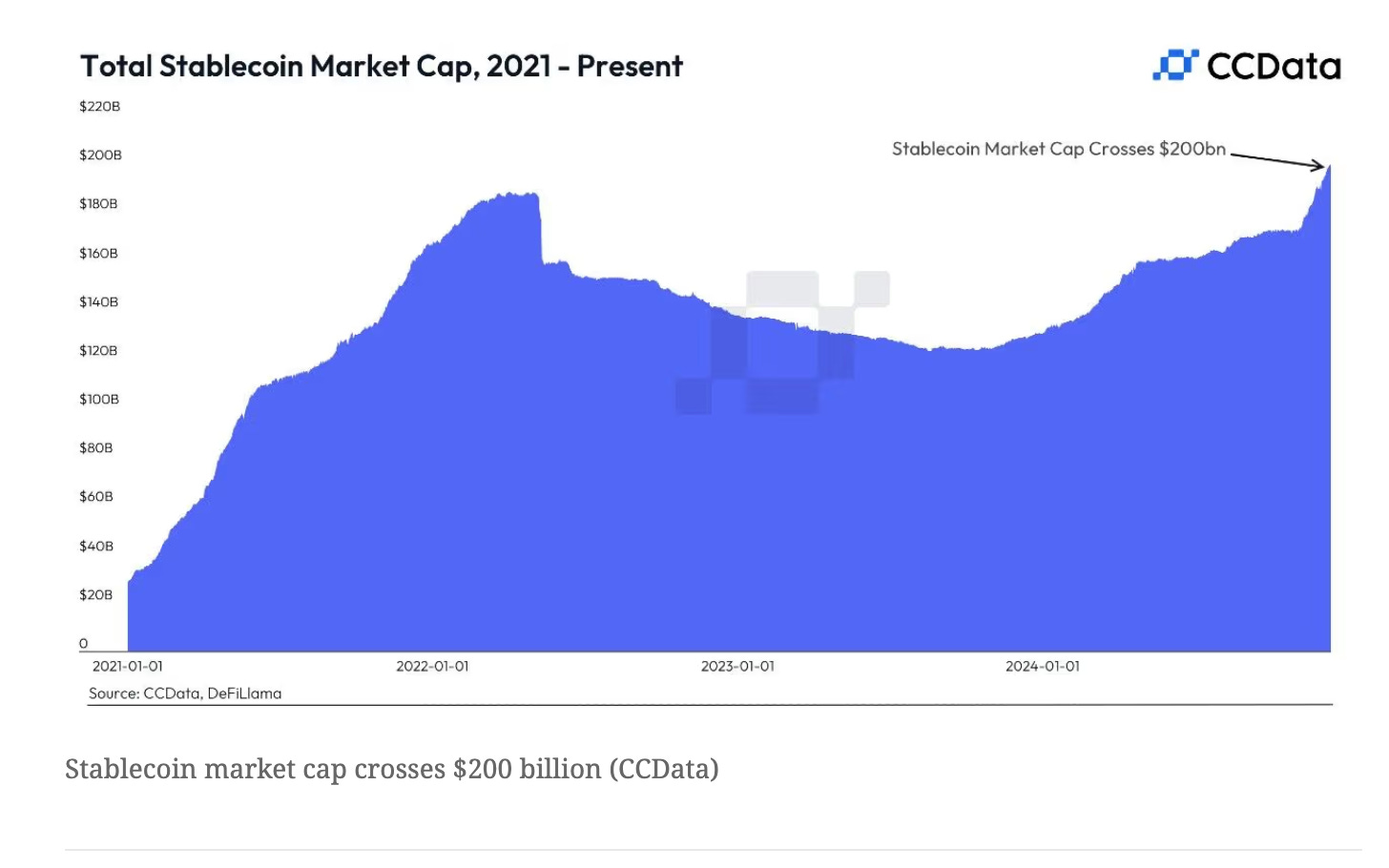

As the experience of 2023-2024 showed stable coin were vulnerable not only to shocks in the crypto universe, when bitcoin prices moved by large amounts. But they were also vulnerable to bank runs, like the one at Silicon Valley Bank, which had close ties to the fin tech and crypto community. Most importantly, however, the stablecoin system, like the eurodollar system as a whole was put under severe strain by Fed interest rate policy. Unsurprisingly, higher interest rates at the core of the dollar system tend to drain funds towards the USA. As an ECB paper by Aldasoro, Cornelli Minesso, Gambacorta and showed, that means pressure both on the entire system of dollar users worldwide and on “offshore” systems like stablecoin. As a result, in 2023 stable coin entered what seemed like a retreat.

In response to that recession, the most searching analysis of the stablecoin-eurodollar analogy to date was presented in November 2023 in the form of a BIS paper co-authored by Aldasoro, Mehrling and Neilson. Starting from Mehrling’s view of the monetary system - the so-called “money view” - the analogy between stable coin and eurodollars is obvious. But so too is the vast gulf between the deep network of liquidity that buttresses the eurodollar and the flimsy, crude and at time ludicrously self-referential systems put in place in the hope of supporting stablecoins. The TerraUSD death spiral in the spring of 2022 was a particularly egregious case in point.

The first wave of scholarly work on the stablecoin-eurodollar connection was published very much under the influence of the interest rate hike and the crypto recession of 2022-2023. Since then stablecoins have recovered along with the rest of the crypto ecosystem. With Trump’s election victory there was a surge in stablecoin activity to new record levels.

Source: Coindesk

It is against this backdrop that Austin Campbell returns to the charge on OddLots touting stablecoin as a eurodollar substitute.

Campbell thinks seriously about modern money. On the OddLots show he is excellent about the rank absurdity of anti-state libertarians supporting the idea of a national bitcoin reserve. There is an extraordinary moment in the conversation in which Campbell discusses the prospect of the United States launching drone strikes on “miners” in rival countries - miners in this case being banks of computers solving ever more difficult mathematical problems to “mine” bitcoin. Be careful what you wish for, he opines. Define something as strategic and states will do what states do.

Unsurprisingly, against this backdrop. when it comes to the future of stablecoin Campbell prefers analogies from the tamer world of tech and social media. Stablecoin, he tells us, are at a stage that could be compared to that of the internet when AOL was the main browser, or the bygone days on social media when MySpace was the main platform. He hails the prospect of stablecoin graduating into the Facebook era. The analogy is telling for its ambition - the pace of facebook’s growth was rapid; its reach is vast - but also for the way it sidesteps the political and historical issues that were so powerfully highlighted by Menand and Younger in their account of the rise of the eurodollar.

Crypto it would seem is caught in a bind. It owes its current boom to political factors, above all the election of Trump 2.0, whose views on crypto have undergone a huge change. The big hope from the respectable side of crypto is that now, with the Republicans in charge, regulatory clarity will be restored. And crypto will be spared what they regard as legal warfare on the part of Biden-era regulators. And yet when it gets serious that political backdrop has to be disavowed.

That dance of the veils is not uncommon in monetary affairs. It was also part of the history of the eurodollar - a private commercial device with eminently geoeconmic and even geopolitical functions. But the drift of the current moment is clear. And one is tempted to say that we will really know when stablecoins are growing up when its most articulate advocates stop harking back to the depoliticized era in which social media and the internet emerged, and when they start taking the eurodollar analogy, with all its attendant political economy, more seriously.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here:

Dear Adam,

if I could make 2 points, very briefly.

1. The "if eurodollars are dollars that circulate offshore, stablecoin are onchain crypto assets that are tethered to the conventional" statement assumes as premise that eurodollars and crypto assets would be interchangeable. They are not. Eurodollars are money, cryptos are not. Nor will they be any time soon. Money is a utility, cryptos are shady, zero-sum schemes to get filthy rich in record-breaking time. So this entire soliloquy is just meaningless.

2. Austin Campbell has a remarkable conflict of interest in this case. He's leveraging his NYU credentials for selling snake oil. When, if ever, he'll be able to recoup his ethical values he flushed down the toilet a while back, one specific, ethically sound, responsible and sensible request he should make is to ask Tether to hold itself to neither more, nor less, but the same exact quantity and quality of financial scrutiny that any other eurodollar bank is exposed to currently. Until such time he can cordially fuck off and bullshit someone else.

Kind regards,

A fellow traveller.

This was a fascinating read, thank you so much Adam. A big fan of the Menand-Younger series.

Lots of literature (including the Aldasoro et al. paper you mentioned) has also been written about how stablecoins compared to money market funds, as both are backed by reserves that may suddenly become illiquid, thus leading to break-the-buck scenarios.

On the other hand, the eurodollar analogy underscores their role as unregulated, parallel forms of money that exist outside the direct control of central banks. Unregulated only in the US though – the EU has posed capital and liquidity regulations on stablecoin issuers. Nonetheless, the fact remains that 99 % or so of fiat-based stablecoins are denominated in the US dollar.

I do not think these two different analogies are opposed to each other, quite the opposite, I think they complement each other. Curious to hear if you have thoughts on how these two analogies compare.