Chartbook 347 The trouble with transitioning: putting energy history back on its feet.

Carbon notes #19

Conventional climate policy is organized around two ideas. First, climate stabilization will be achieved through comprehensive transition away from fossil fuels. Second - the optimistic theory has it - this shift will be propelled by the falling cost of renewable energy. In the course of electrifying everything, clean power will become cheaper and more abundantly available than ever before and that will do the trick.

It is a comforting vision. And it does capture elements of real experience. There are individual sectors in which phase-like transitions have occurred.

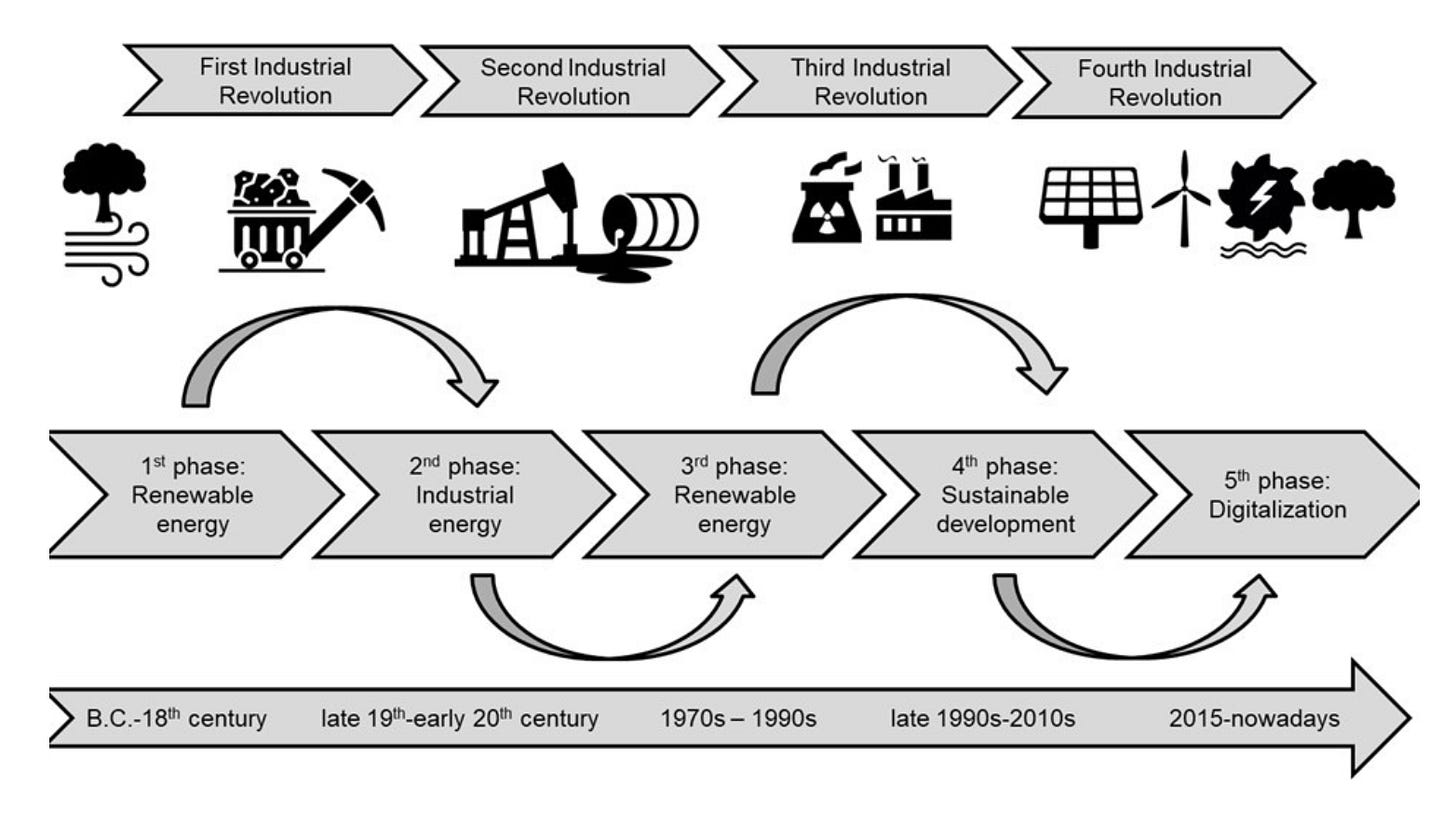

Over the last two centuries, American transport is one such sector - from biomass, to coal, to petrol (the US powers its freight trains with diesel).

Gas and renewables have ended the use of coal in power generation in major economies like the UK. The cost of renewables really is plunging.

But, conventional thinking in climate policy doe not stop with these facts. It stitches them together to form a pleasingly coherent vision of the future in which new technologies, following familiar historical patterns will provide the answer to the climate crisis.

The inescapable conclusion of two important books published last year is that this is where we go wrong. This construction of history and its projection into the future gives a fundamentally misleading picture of the challenge ahead.

More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy by Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, which I recently reviewed in the LRB, shows that the idea of the energy transition as a general experience in fact runs counter to the historical trend.

Brett Christophers The Price is Wrong, which I will review in a separate post, throws cold water on the idea that falling energy costs will do the trick of driving the transition to renewables.

Taken together the two books are a double-barreled blast against conventional optimism on “the energy transition”.

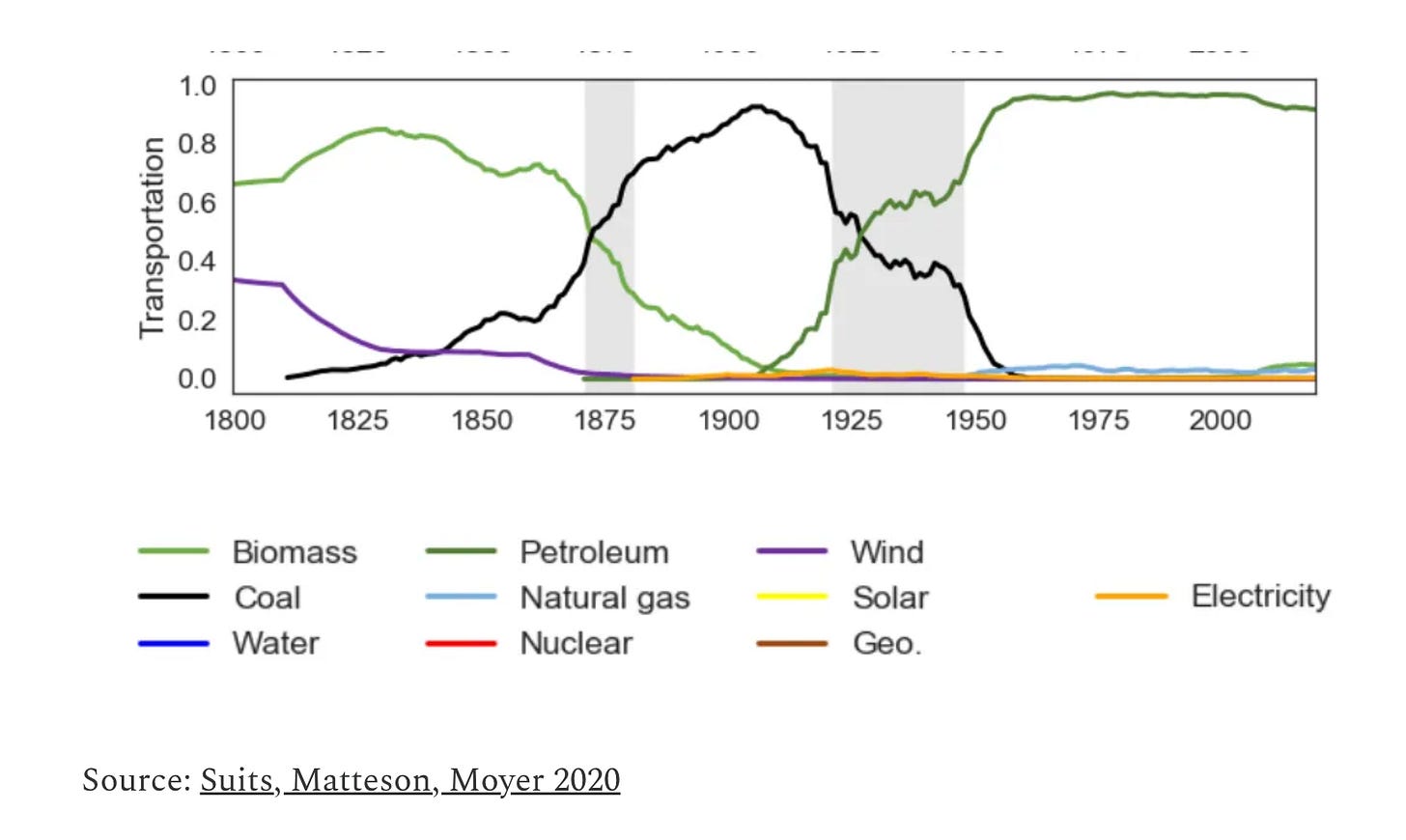

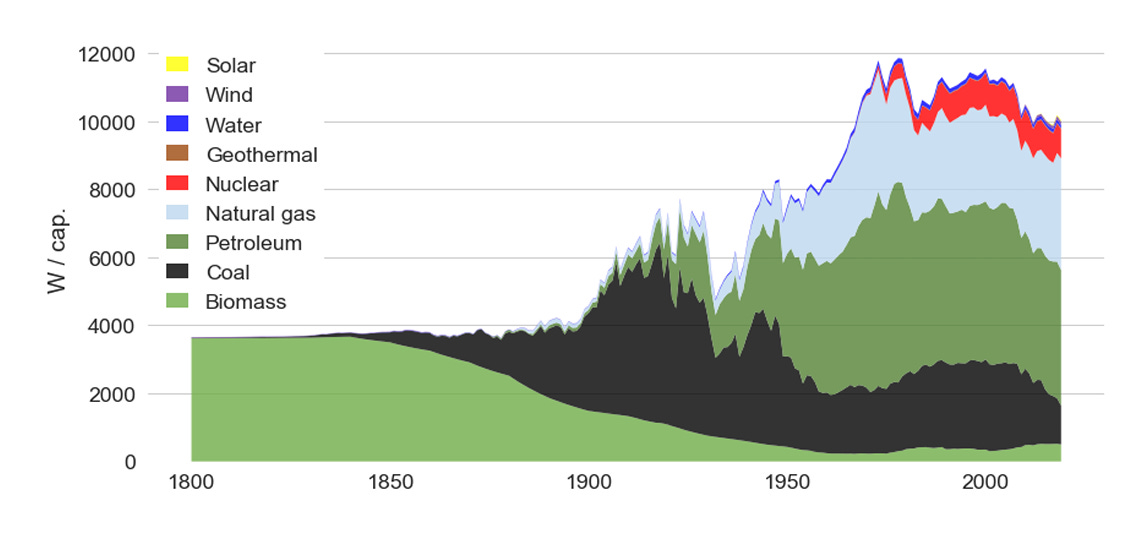

The basic idea behind Fressoz’s argument is immediately evident from any compilation of data on energy use or CO2 emissions. If we look beyond the narrow confines of particular sectors to measure overall energy use at a societal or global level, far from there being a sequence in which coal replaces organic energy, followed by oil and then nuclear power and then renewables, what we see is the accumulation and agglomeration of energy sources. I discussed some of these basic empirics back in March 2023 in Carbon Notes #1.

At the global level the story looks like this. Collectively we have mobilized more and more energy from an increasingly diverse array of sources. Even the use of traditional biomass has not decline in absolute terms. More poor people consume more firewood for fuel. More rich people eat meat that drives deforestation.

Even if we focus on just one advanced society and put energy use in per capita terms - rather than allowing for overall growth in population - this is the picture that emerges.

Source: Suits, Matteson, Moyer 2020

In the US today, biomass, coal, oil, natural gas, nuclear and renewables all feature in the energy mix. Until the early 2000s coal was very significant (because of its use in electricity generation). The new renewables had, by the 2010s, barely made a dent. Not much sign of transitions here!

The conventional vision of suppressing the use of all fossil fuels in the next few decades by way of an “energy transition”, far from being supported by history, is utterly radical. That does not mean it is impossible. It is just misguided to imagine that it can be predicted from past historical experience.

Fressoz’s argument, rather than being maverick is better thought of as providing a highly sophisticated articulation of stylized facts that should guide all thinking about energy history and the energy futures.

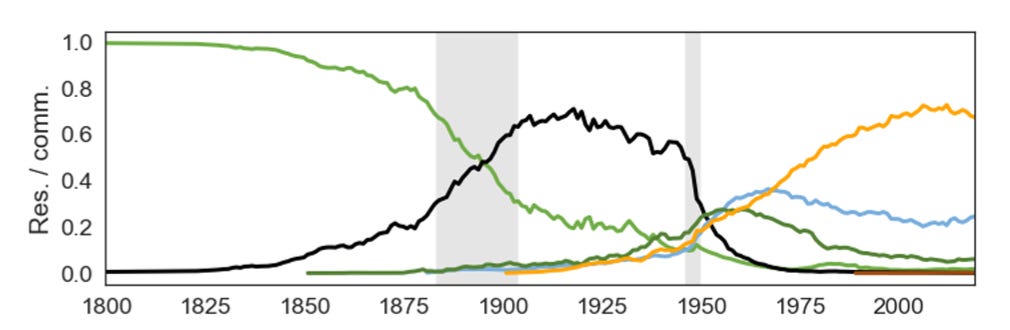

Energy transitions are not so much a general historical phenomenon, or societal regularity, so much as a sectoral and regional particularity dependent on technologies and complex and long-lasting investments in infrastructure. The displacement of biomass by coal and the rapid displacement of coal by electricity, oil and natural gas in US domestic and commercial uses, is a case in point.

Source: Suits, Matteson, Moyer 2020

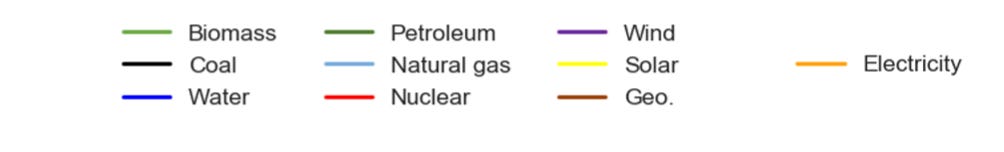

This looks like a neat case of energy transition, except that behind yellow electricity line lurks coal! Coal’s use in power generation was surging precisely as its direct use in households and industrial applications was collapsing.

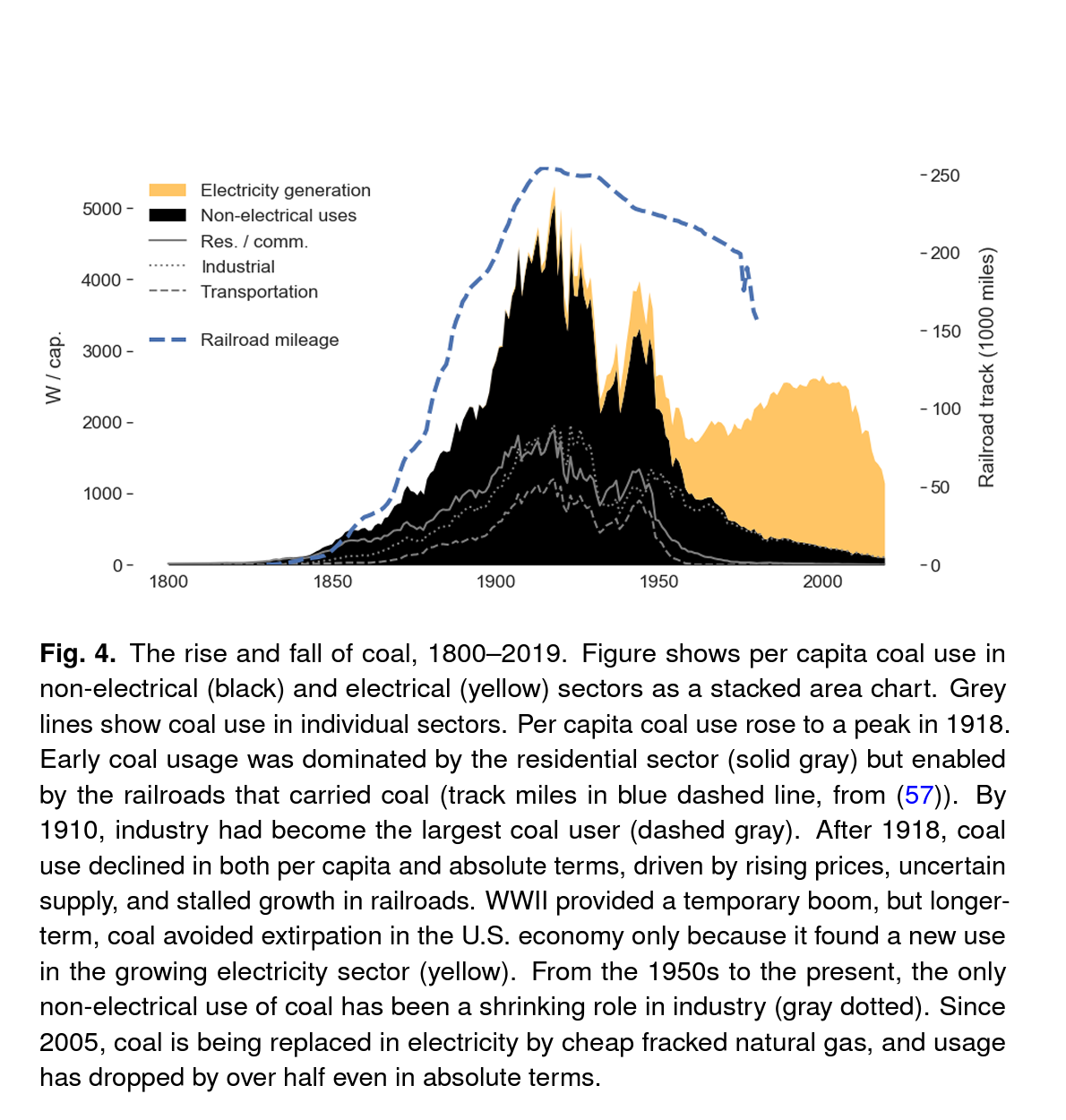

Source: Suits, Matteson, Moyer 2020

As On Barak explained in conceptual and historical terms, in his fascinating book on coal in the British Empire in the 19th century, Powering Empire. How Coal Made the Middle East and Sparked Global Carbonization (California, 2020), the difficulty in thinking about the complexity of modern energy use arose with coal in the 19th century:

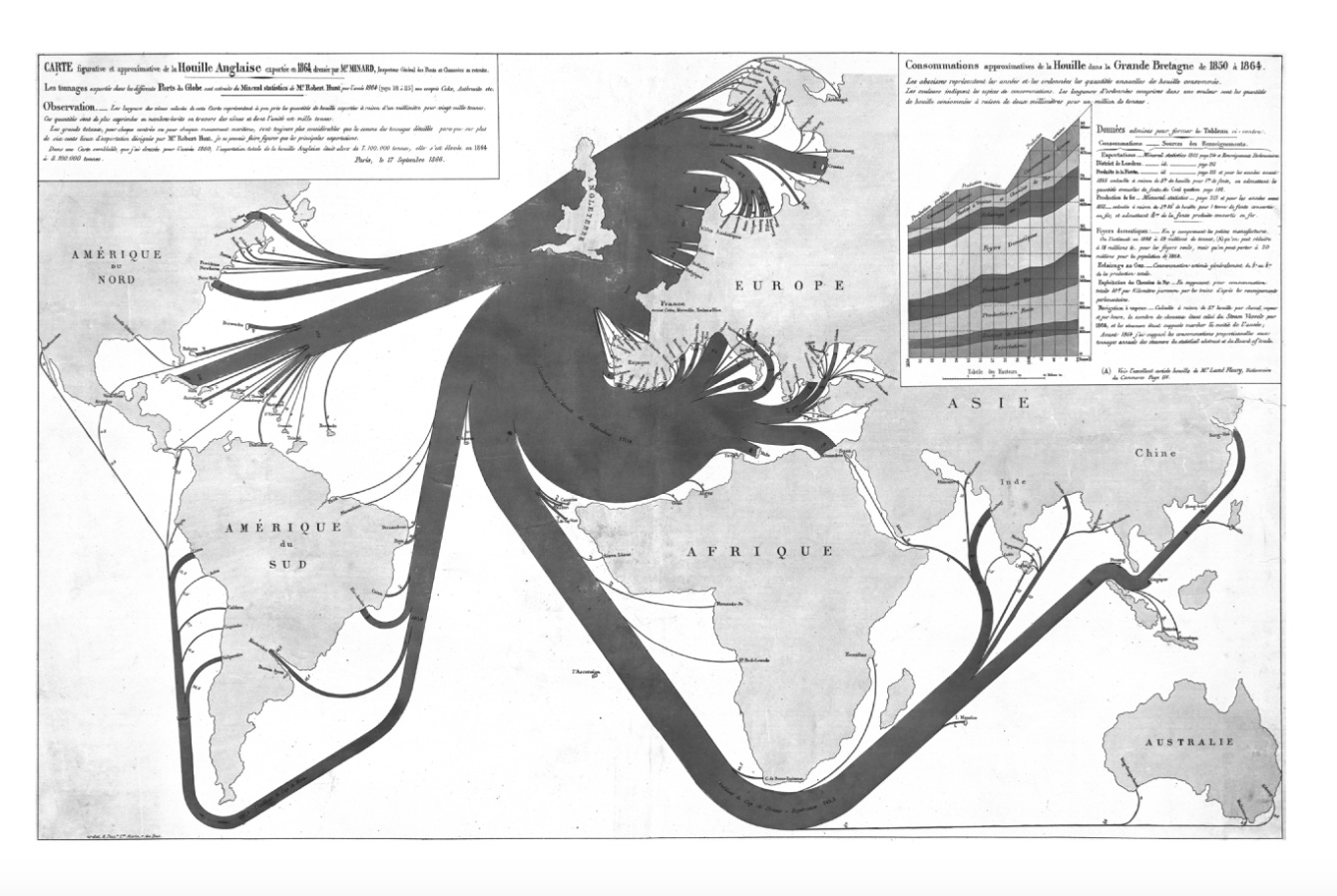

As Barak points out, part of the problem in understanding the true complexity of modernity is the very conception of “energy”. 19th-century physics defined energy it as a universal force capable of being converting into different forms. It was thus fungible and universal. This conception set the stage for the stories of energy transition which both he and Fressoz expose as fragile historical constructs. Coal became the quintessential expression of that new idea of energy, allowing a mapping of the world in terms of energy flows.

Charle Joseph Minard, British Coal Exports 1864

That same universalized conception of coal as energy also then allowed one to imagine, coal being displaced by oil, which in turn will be displaced by nuclear power or renewables. What this ignores are the peculiar characteristics of each energy source, which means that as new sources of energy are introduced, the old are not generally discarded or simply replaced, but reconfigured and repurposed in new ways. Again Barak puts the point very well:

Fressoz’s essential book generalizes the argument made by Barak. On a far broader canvass he demonstrates not only the profound entanglement of energy systems but how the notion of energy transition took hold at the beginning of the 20th century and how it was then handed down across the period of nuclear enthusiasm after World War II, to the crisis epoch of the 1970s and 1980s.

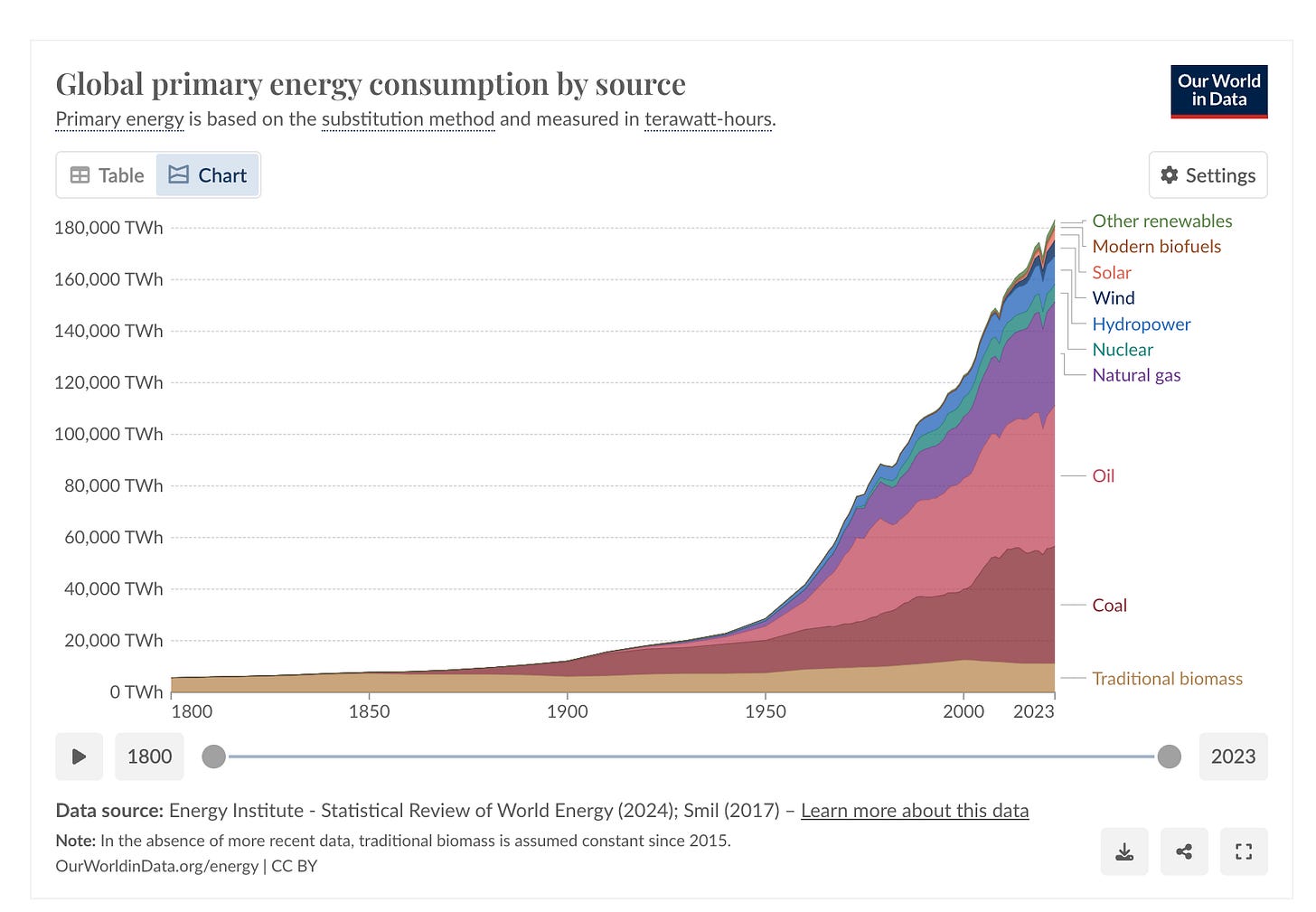

Barak confines himself to the 19th and early 20th centuries. Fressoz stops short in the early 1990s. This is a shame because it is really in the last quarter century that their basic thesis has been vindicated on a far larger scale than ever before in history. Where the energy transition model of history fails most spectacularly is with regard to the process of economic growth that defines our present, the growth of China since the 1990s.

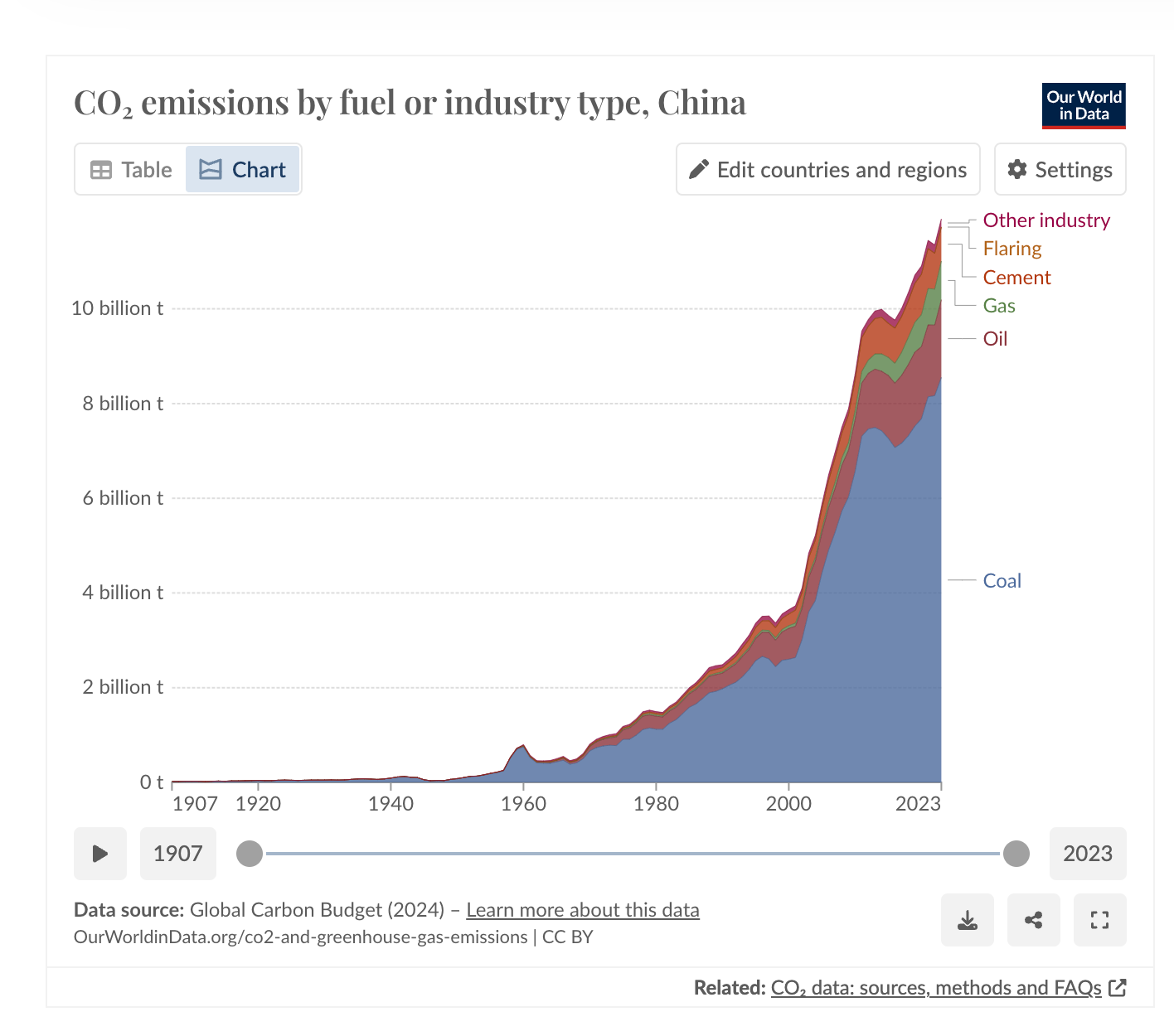

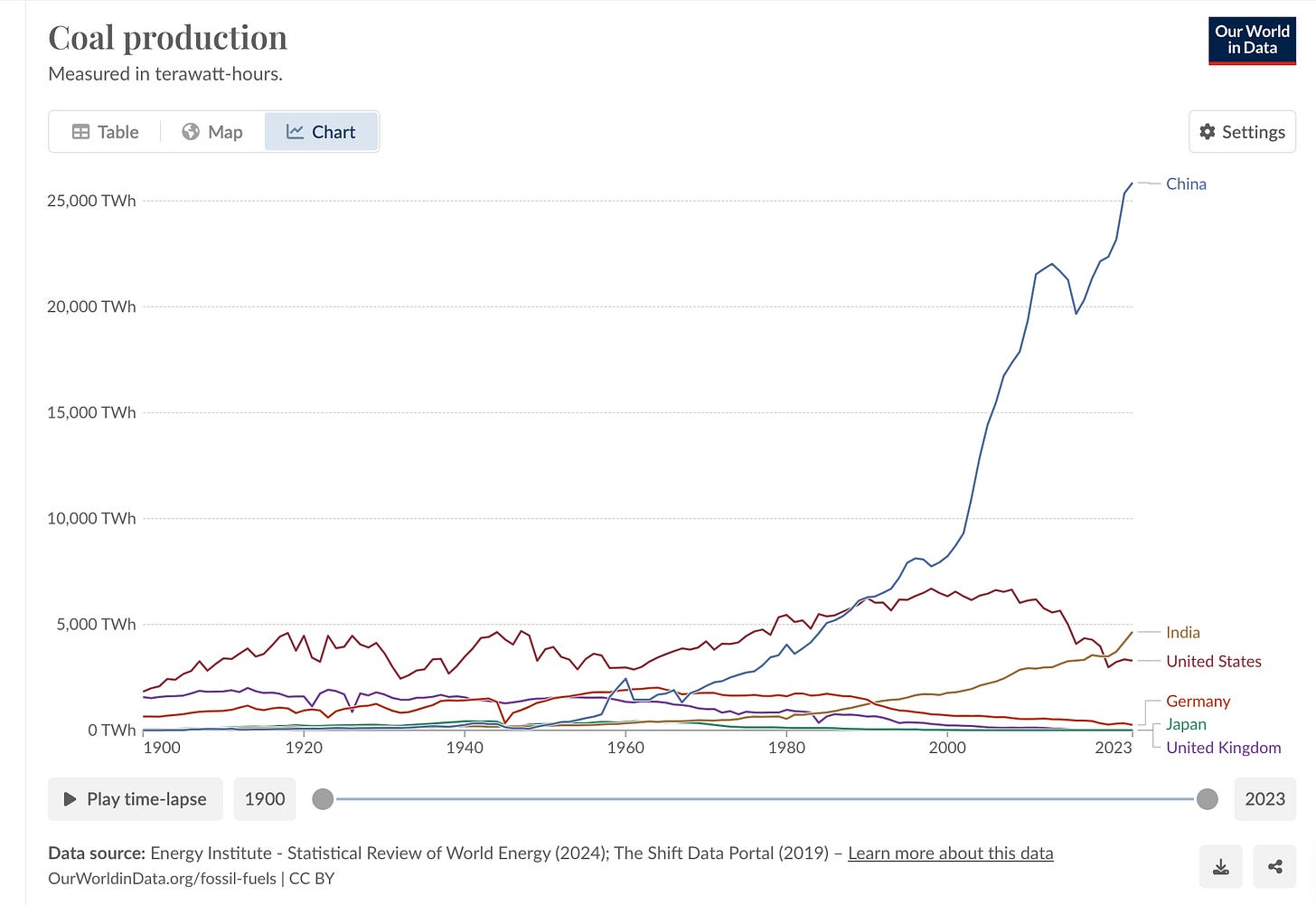

China’s phenomenal economic growth in the early 2000s which propelled the greatest urbanization drive the world has ever and has made China into the high-tech hub for one third of global manufacturing, was powered not by oil or nuclear power, but by “old-fashioned” coal.

Source: Our World In Data

Barak likes to talk about provincializing Western ideas of energy. It is hard to think of a graph which does that more dramatically than the one below.

The entire heavy industrial history of the West is put in the shade by China’s mobilization of coal in the last quarter century. It is this which makes clear the truly radical nature of the project of decarbonization that lies ahead, for those who still take it seriously. It involves a break from history in the double sense first that it involves the winding down of the entire interconnected system of fossil fuels and second that this unprecedented reconstruction can only be led by Asia. As the case of Chinese dominance in solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles demonstrates, this comes as a truly wrenching shock, a shock which America’s political system shows no sign of being able to digest.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters, click here:

we're cooked

Bottom line.... we will use what is most effective and least cost without much constraints.