Chartbook 346: Against overcorrection. Yellen's Treasury defends the legacy of Democratic fiscal policy.

When a party loses power there is a temptation to look back on policy and to ask what went wrong. In the case of the Democrats this started even before they lost. Indeed it started so soon they had barely taken office. Already in the spring of 2021 ex Treasury Secretary Larry Summers was preemptively denouncing the fiscal policy of the White House and the Democratic majority in Congress as irresponsible and a sure fire electoral gift to the Republicans - on account of the inflation that he thought would follow.

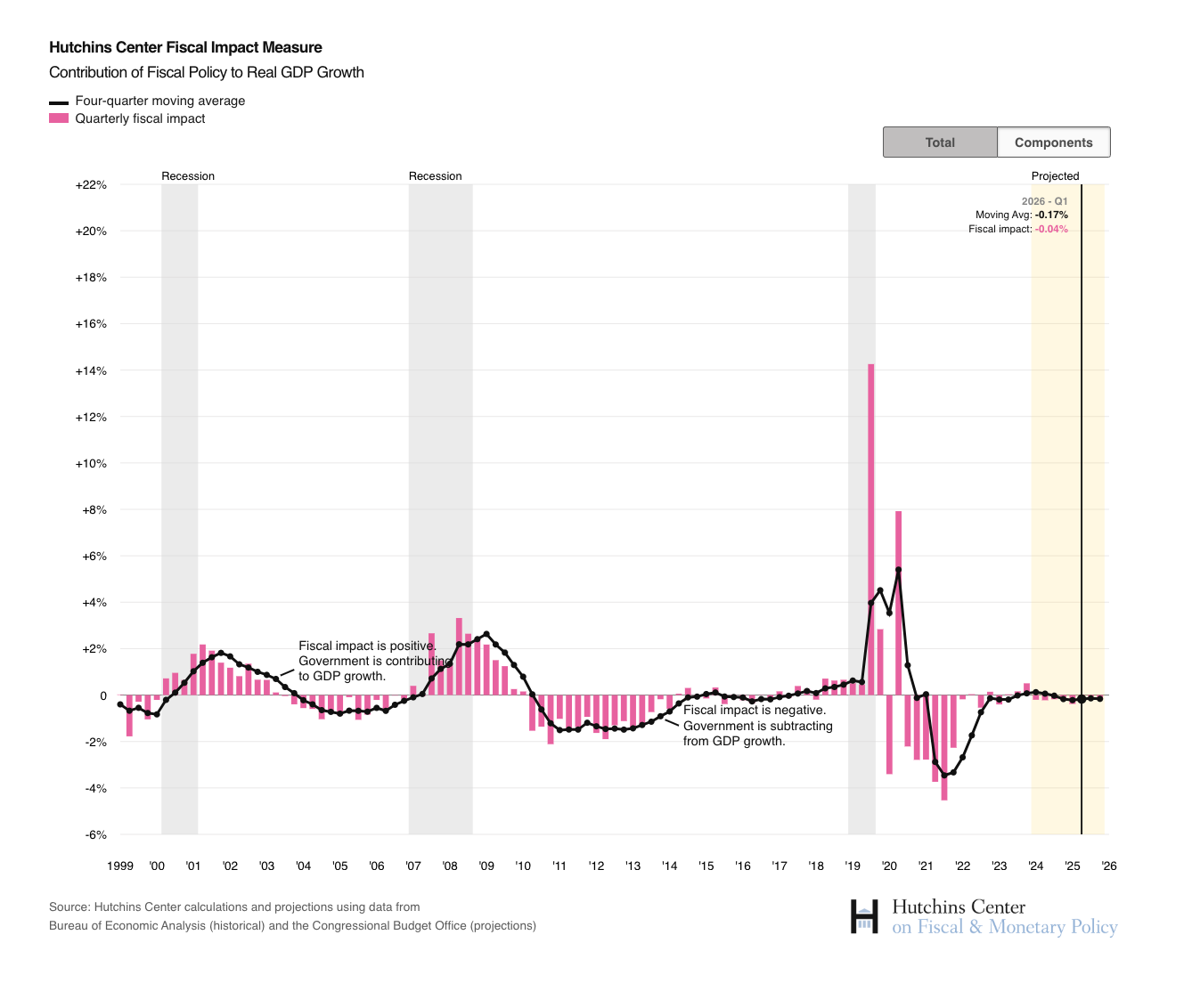

The scale of fiscal policy was certainly dramatic. Between Q2 2020 and Q1 2021 Congress approved the most dramatic series of fiscal programs in peacetime history.

Though they did better than expected in the mid-terms in 2022, in November 2024 the Democrats lost to Trump. Inflation was widely cited as a reason for voter dissatisfaction. Does this vindicate the critics and suggest the need for a fundamental revision of policy?

In a recent column, Martin Sandbu at the FT warns that the Democrats are in danger of overcorrecting policy. I am delighted to say, that on this point I strongly agree with Martin.

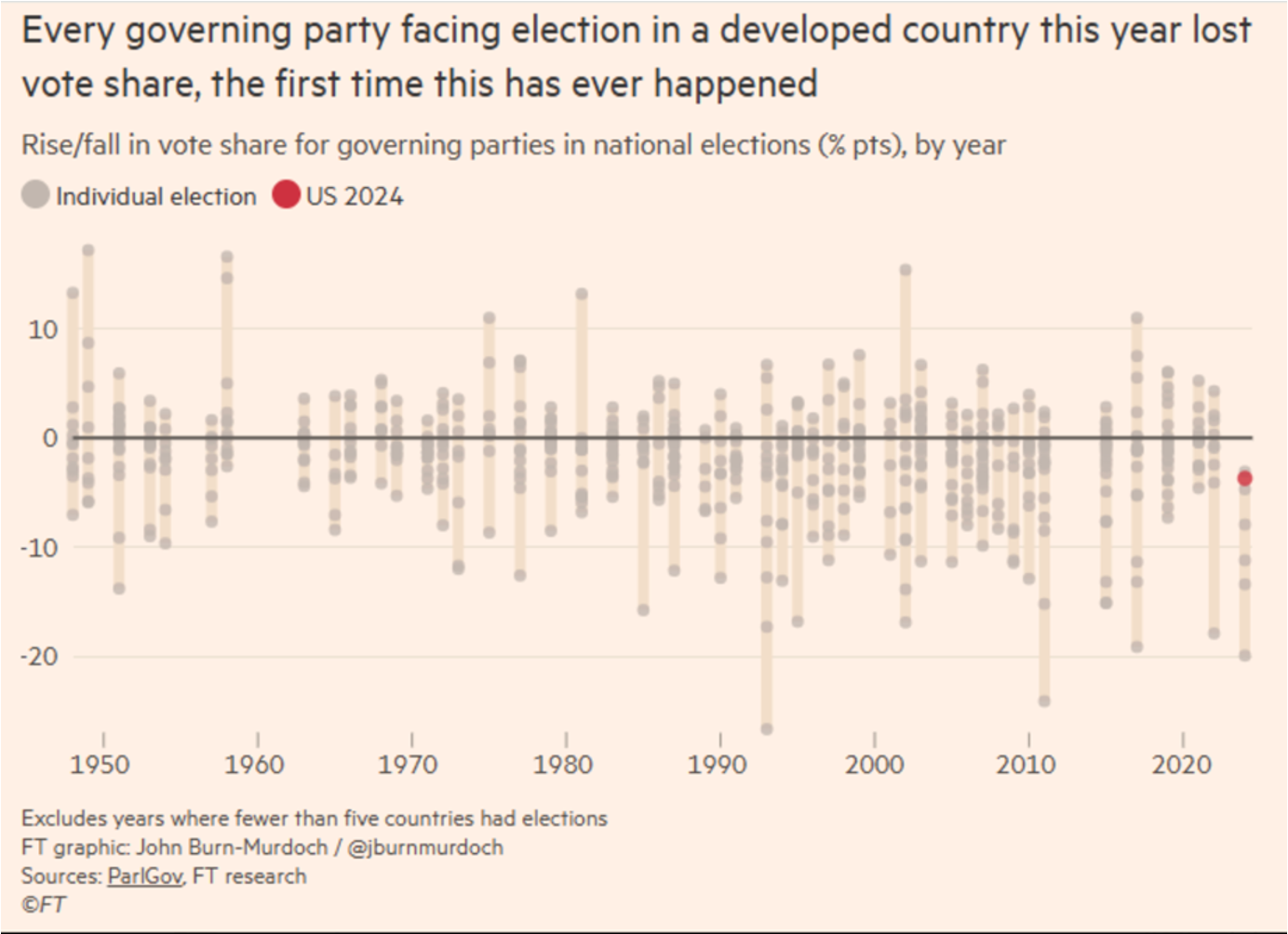

To start with, what are we trying to explain? The Democrats lost, but by the standards of incumbents worldwide their defeat was relatively marginal.

When we consider the extraordinary weakness of Biden as a candidate, one might reverse the question and ask whether the remarkable track record of economic policy over the last four year, in fact, helps to explain why the Democrats did so much better than virtually every other governing party.

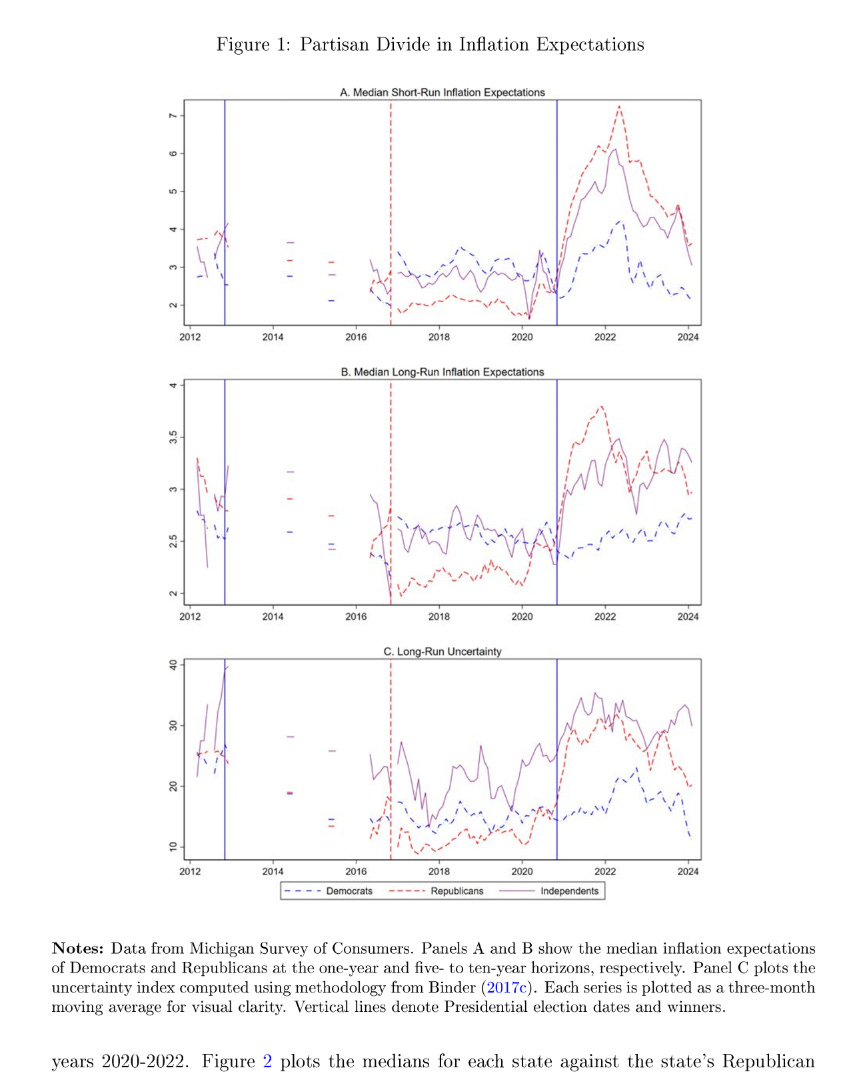

Secondly, we have to ask how the inflation variable and above all inflation expectations function in American political economy today. Even from a casual inspection of readily available data, it is clear that economic sentiment and partisanship in contemporary America are not independent variables. The effort to explain voting behavior by reference to feelings about the economy is naive because reported sentiment about the economy is clearly tied to partisanship.

This doesn’t mean that we should dismiss the real socio-economic problems of chunks of the electorate. We just shouldn’t treat those issues and the salience and meaning voters give them as separate from broader process of political self-fashioning and orientation. Economic sentiment is not an independent cause. If someone declares that worries about the cost of living swung them to vote for Trump in 2024, it would be naive to imagine that if Biden’s economic policy had delivered a marginally lower inflation rate that voter would have swapped back to the Biden camp.

In the United States today, political partisanship and worldview, individual socio-economic experience and macroeconomics are profoundly entangled. This effect is so powerful that, as a recent paper by Carola Binder, Rupal Kamdar and Jane M. Ryngaert shows, partisanship shapes the macroeconomic environment itself.

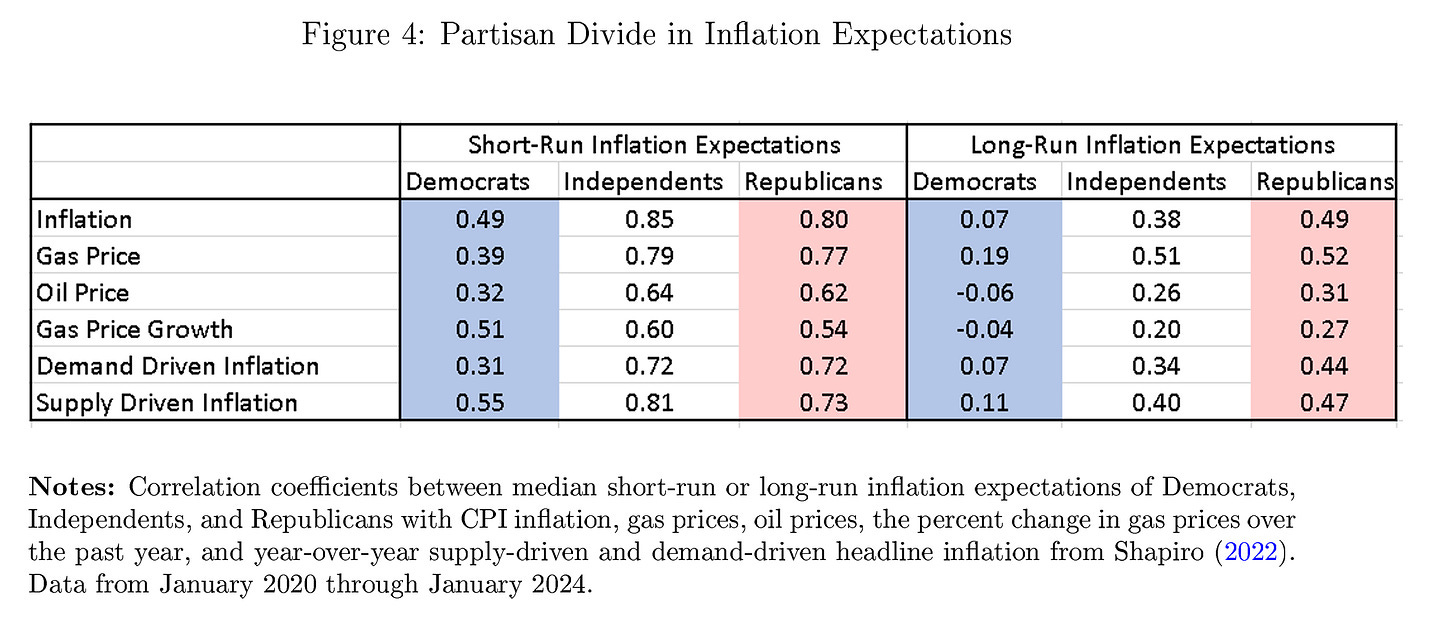

We document that, during the COVID-19 era, the inflation expectations of Democrats remained strongly anchored, while those of Republicans did not. Republicans' expectations not only rose well above the inflation target, but also became more sensitive to a variety of shocks, including CPI releases and energy prices. … Counterfactual exercises imply that, had all expectations become as unanchored as those of Republicans, average inflation would have been two to three percentage points higher for much of the pandemic period, ceteris paribus. …. Before 2020, members of the President's party have inflation expectations that are about 0.92 percentage points lower than those of independents and members of the opposition party have expectations about 0.11 percentage points higher, so the gap between members of opposing parties is about 1.0 percentage point. Since 2020, those effects have more than doubled in magnitude, and the gap between Republicans and Democrats is 2.5 percentage points. Males, college-educated respondents, and homeowners all have systematically lower expectations than their survey counterparts, but the partisan gap in in ation expectations is the largest in magnitude.

After 2020, whereas Republican inflation expectations tracked the current inflation rate, Democratic one-year inflation expectation remained closely aligned with professional forecasters in expecting inflation to be transitory. These differences mirror differences in attitudes to expertise more generally. The Republican faithful are disproportionately anti-vax and suspicious of all kinds of expertise. Unsurprisingly, with Donald Trump now reelected, Republicans now have a far more sanguine inflation outlook.

One variable that weighed heavily on Republican inflation-expectations is the price of oil. The correlation between short-run inflation expectations and the gas and oil price is roughly twice as large for Republicans as it is for Democrats.

The point here is not to pillory Republicans for the way in which they form their economic outlook. No doubt, their outlook forms part of a settled outlook, which makes it seem sensible for them to express the views that they do.

The barb is directed at technocratic policy advocates, especially those in the Democratic camp, who discuss inflation expectations and unemployment-inflation trade offs as though they were non political variables to be optimized by policy maker and on that basis make highly conservative recommendations to the Democratic camp. In America today, government driven by fear of “de-anchoring” inflation expectations is government driven by fear of Republican and “independent” voters whose expectations are far more likely to de-anchor. It is a populist variant of the unspoken politics of “confidence”.

A straight forward and powerful defense of Democratic economic policy in 2021 - and really the Congressional Democrats should take credit for the stimulus programs of 2020 too - was delivered on January 15 by out-going Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. this is backed up by a substantial Treasury report. I will quote at length:

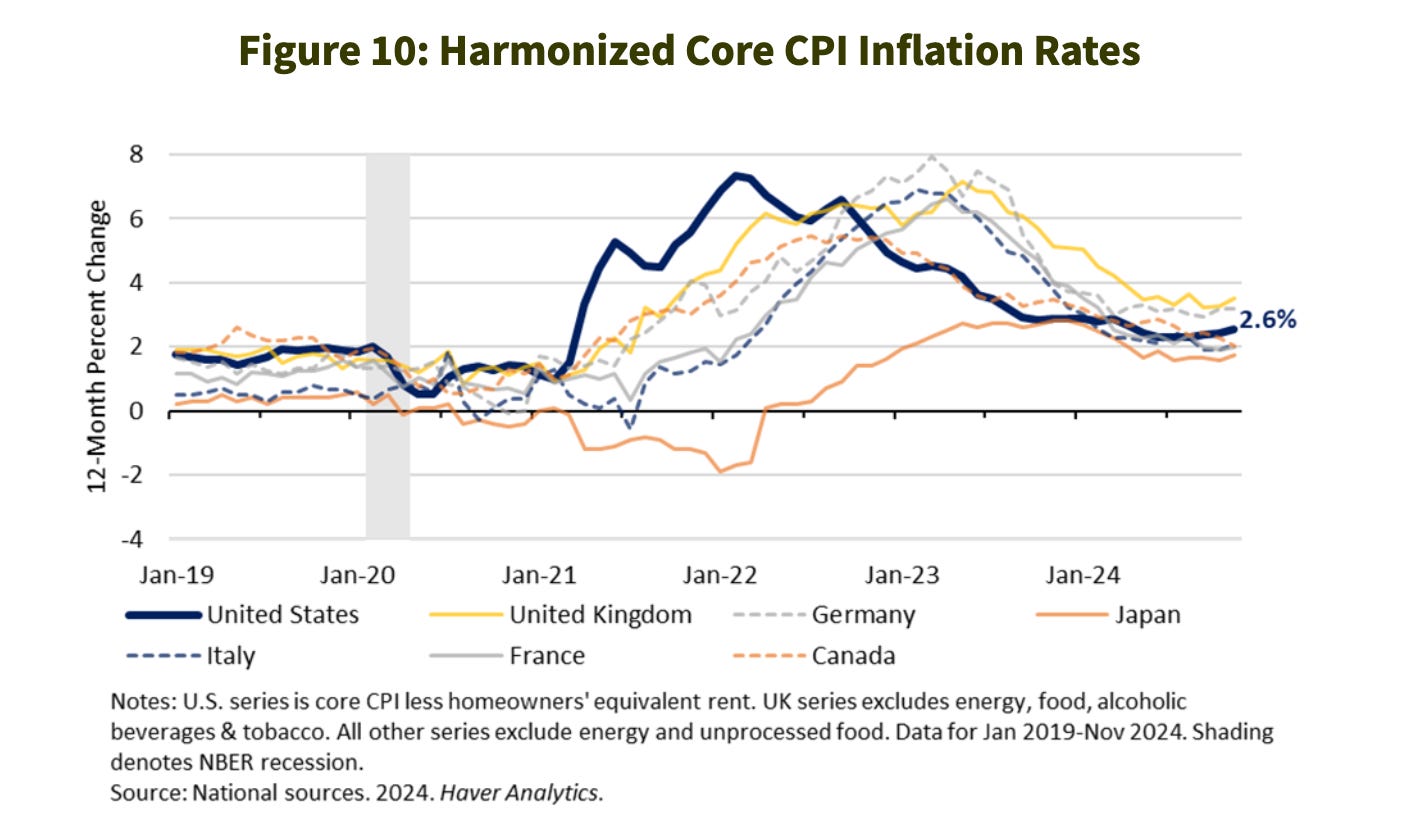

First, consider comparisons to other advanced economies. Virtually all advanced economies experienced a significant spike in inflation. But in the United States, inflation fell earlier than in other G7 economies.[14] At the same time, America enjoyed strong growth. Real GDP now exceeds pre-pandemic levels in all G7 economies. But it grew by more in the United States: by 11.5 percent from the end of 2019 to the third quarter of 2024, followed by 7.3 percent in Canada and 5.6 percent in Italy.[15] This is largely attributable to robust U.S. productivity growth, which far outstripped productivity gains in other G7 economies.[16]

At the same time, America quickly achieved and has subsequently maintained a uniquely strong labor market with notable real wage gains. In the period from Q4 of 2019 to Q2 of 2024, the United Kingdom is the only other G7 country that also experienced substantial real wage growth. Real wages grew modestly in Canada, remained essentially unchanged in France, and declined in Germany, Japan, and Italy.[17] The Economist magazine’s mid-October issue perhaps sums it up best, designating the U.S. economy the “envy of the world.”

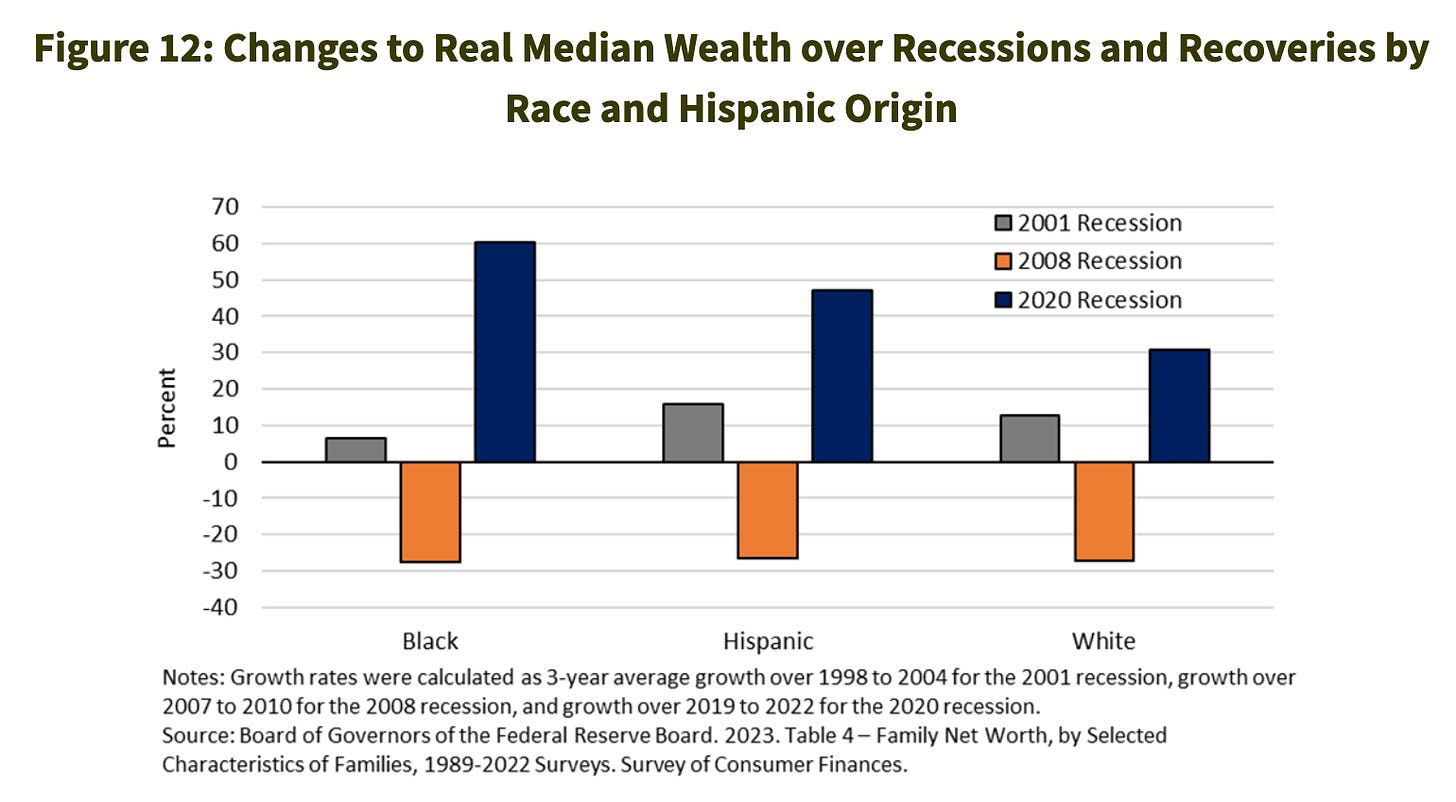

Comparing this recovery to past ones further underscores the strength of our expansion. While the COVID recession entailed the largest spike in unemployment in living memory, the U.S. unemployment rate declined to its pre-pandemic level in just two years. This contrasts significantly with longer than four years in the 1990, 2001, and 2008 recessions.[18] The historic 37 percent increase in real median household wealth from 2019 to 2022 also stands in marked contrast to the 2007 to 2010 period, when real median household wealth instead fell by 39 percent.[19] And business investment fell less and recovered faster as a share of GDP than in prior recessions, with businesses investing an estimated $625 billion more during this expansion than if investment had followed historical patterns.[20] This historically impressive investment performance reflects domestic and foreign investors’ confidence in the stability and productivity of our economy.

Comparisons to economic forecasts from various points during the past four years also demonstrate the strength of the U.S. recovery. In the fourth quarter of 2021, real GDP exceeded the Blue Chip consensus forecast from October 2020 by more than four percent.[21] The economy then continued performing better than expected. Even in October of 2022, Blue Chip forecasters expected that a recession was more likely than not in 2023, with many prominent forecasters asserting that a recession was a near certainty.[22] As we all know, that recession did not come to pass. In fact, the U.S. economy, remarkably, is expected to be more than 10 percent larger by the end of 2024 than the IMF forecasted in October 2019, before the onset of the pandemic.[23]

Alongside these three comparisons, we should also consider a counterfactual: how inflation and labor market outcomes would have differed under alternative policy choices. With respect to inflation, it’s true that the prices of many everyday goods soared in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, placing a major strain on many American households. However, as the supply disruptions that drove much of this inflation abated and labor market disruptions subsided, the pace of inflation cooled dramatically. With respect to the labor market, support from the American Rescue Plan substantially offset the income gaps confronting roughly 10 million people[24] who had become unemployed or had left the labor force by the end of 2020. That both averted significant hardship and supported demand, which allowed Americans to get back to work quickly. The rapid decline in unemployment enabled the United States to avoid labor market scarring—the erosion of skills and reduced employability that can result from long periods of unemployment—and thus avoid an associated reduction in future potential output.

Now, consider the likely consequences of an alternative fiscal response, one solely aimed at preventing the post-pandemic surge in prices without considering the consequences for unemployment. To prevent that inflation surge, fiscal policy would have had to be much tighter. Indeed, a contractionary fiscal policy would likely have been needed to offset the inflationary impact of the pandemic-induced contraction in supply. Such a policy would have withheld critical aid from households and businesses and would likely have led to far lower output and employment. That could have meant millions more people out of work, households without the income to meet their financial obligations, and lackluster consumer spending.

An important “what-if” exercise would ask: how much more unemployment would have resulted from a fiscal contraction sufficient to keep inflation at the Fed’s 2 percent target? The answer is “a lot,” although the exact magnitude depends importantly on some key parameter values, particularly the Phillips curve slope, which measures the sensitivity of inflation to a demand-induced contraction in output. Most estimates of the Phillips curve find it to be quite flat. That implies that the employment and output cost of suppressing inflation would have been very substantial. But researchers debate whether such an estimate applied during the pandemic, which was an unusual period characterized by shortages of production capacity in critical sectors and some significant labor market bottlenecks that restrained supply. Some researchers argue for a higher estimate of the Phillips curve slope, and consequently a lower employment and output cost. Such differences notwithstanding, it is widely accepted that some increase in unemployment would have been required to offset the pandemic-induced inflation. Estimates from representative models find that the unemployment rate would have had to rise to 10 to 14 percent to keep inflation at 2 percent throughout 2021 and 2022. That would have meant an additional 9 to 15 million people out of work.[25]

Since the counterfactual is doing quite a lot of the work here, let us dig into the Treasury report that outlines the detail of their argument. A footnote in their report explains to that to make the calculations that result in the horrifying scenario of keeping inflation at 2 percent at the price of 10-14 percent unemployment:

“we assume a linear Phillips Curve. First, we calculate the extent to which monthly annualized core PCE inflation exceeded the target of 2 percent for every month in 2021 and 2022. We then divide those excess inflation estimates by estimates of the Phillips Curve slope (which is the percentage point change in the inflation rate per 1 percentage point change in the unemployment rate) to determine how much higher unemployment would have had to be in each month to bring inflation down to target. We use the following “reduced-form” estimates of the Phillips Curve slope: -0.57 from Ball & Mazumder (2015) and ‑0.34 in Hazell et al. (2022).”

The Treasury economist team know this is back of the envelope stuff, so they add:

Other models suggest that when labor markets are very tight, it may be possible to reduce inflation with smaller rises in unemployment.[26] Nevertheless, the sheer magnitude of the results associated with the simple Phillips Curve model demonstrates the implausibility of pursuing policies that would have fully prevented excess inflation in the face of the supply shocks seen during the pandemic era.

But the bigger question is whether inflation was in fact amenable to fiscal policy at all. As the Treasury report highlights:

Some studies show that even if tighter policy been pursued, the peak in inflation would have been only slightly lower. One analysis from economists at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that with tighter policy, unemployment would have risen to 7 percent at the end of 2022 and remained well above 6 percent through the end of 2023, rather than below the 4 percent we experienced. However, the study found that temporary supply constraints contributed about three fourths of the increase in median CPI inflation during this period and would have occurred anyway. This means that, even with higher unemployment rates, peak core PCE inflation would have been only one percentage point less than the 5.6 percent that occurred.[27],[28] Another analysis found that earlier monetary tightening would have led to unemployment rates over 6 percent going into 2023, with similarly modest reductions in inflation—only about 1 percentage point less than peak for core PCE inflation.[29]

As they conclude by saying:

None of these estimates are unassailable, but they highlight the magnitude of the risks faced by policymakers around the world.

It was a judgement call.

In 2021, the United States was only slowly exiting a truly profound national crisis triggered by COVID, BLM and the final year of the Trump administration. The Democrats had unexpectedly gained a slim majority in Congress to go with the White House. Given the mounting social crisis and the memories of the slow recovery from 2009, they took a calculated risk to prioritize recovery, employment and growth. They were handsomely vindicated. In so doing they proved the doubters wrong. As the Treasury points out:

… because of the tradeoff between inflation and employment, many forecasters thought it impossible to bring down inflation at all without the cost of higher unemployment. As of the end of 2022, Blue Chip forecasters’ probability of a recession the following year was over 62 percent. And, yet, as of the latest data in November 2024, the three-month PCE inflation rate is down to 2.3 percent, the labor market remains historically strong, with the December unemployment rate at 4.1 percent, and forecasters’ assessment of recession risk was cut in half.[30] So far, it appears that a “soft landing” has been achieved, albeit with ongoing risks.

The second Democratic defeat at the hands of Donald Trump is shattering. It may well change the face of America and the world beyond. For areas like climate policy it is an unmitigated disaster. There are, no doubt, many lessons to be learned from the failings Biden administration. The idea that bold fiscal policy is dangerous should not be one of them.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

We have to reckon with the fact that the dominant wing of the Democratic Party simply does not want to improve the country. They and their donors are quite happy to accumulate wealth under Trump, win on thermostatic reaction, and then do nothing once they retake power. Apres moi le deluge.

Very important argument. In conversations with others - Democrats - the wrong lessons are already being learned from this crisis and response. The boldness was critical and had many positive effects. Thanks for putting this together.