As we approach the third anniversary of Russia’s attack on Ukraine, as the world braces for Trump’s inauguration, as the military and diplomatic balance threatens to shift against Ukraine there has been a noticeable shift amongst Western commentators on the economic front. The economy has always been counted as a strong suit for Russia. In an attritional struggle it surely had the advantage. But is that true? Is time, actually, on Russia’s side? Or is the economy perhaps the weak link in Russian strategy?

If we look at the balance between the two sides, such speculation seems implausible. Whereas, Ukraine fights to keep the lights on, Russia is still a prosperous exporter of oil and gas. All the more telling is the drum beat of questions being asked by influential Western voices.

“Here’s hoping” is how Gideon Rachman on twitter reacted to a piece by Finland’s Foreign Minister in the Economist which declared that “Time is not on Russia’s side.”

Martin Sandbu of the FT doubled down with a column declaring:

Russia’s war economy is a house of cards. The financial underpinnings look increasingly fragile. President Vladimir Putin’s conceit has been that he can fund this war without financial instability or significant material sacrifices, but this is an illusion … The most important thing Russian President Vladimir Putin tries to impress on Ukraine’s western friends is that he has time on his side, so the only way to end the war is to accommodate his wishes. The apparent resilience of Russia’s economy, and the resulting scepticism in some corners that western sanctions have had an effect, is a central part of this information warfare. The reality is that the financial underpinnings of Russia’s war economy increasingly look like a house of cards — so much so that senior members of the governing elite are publicly expressing concern. They include Sergei Chemezov, chief executive of state defence giant Rostec, who warned that expensive credit was killing his weapons export business, and Elvira Nabiullina, head of the central bank.

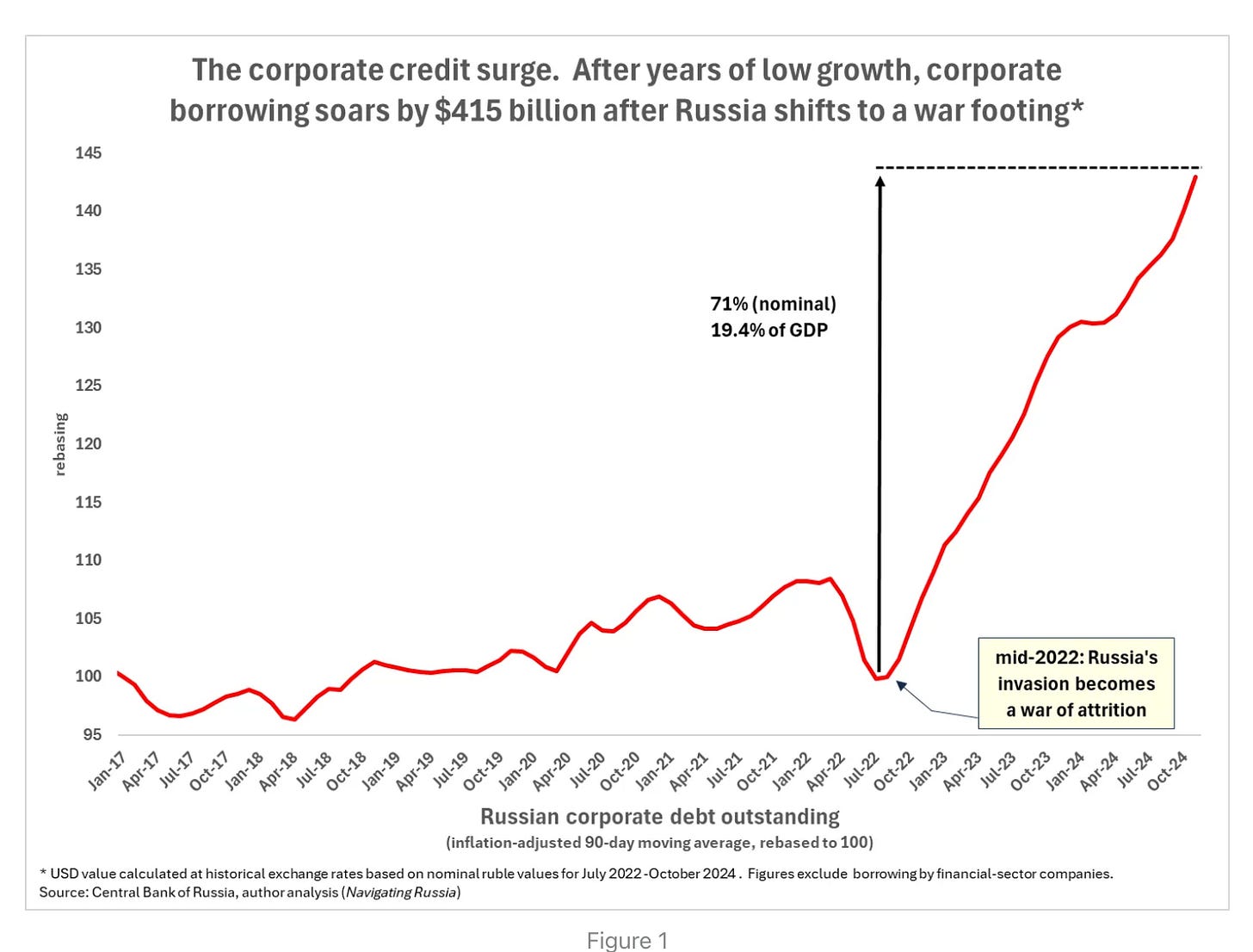

Already in November 2024 Tony Barber in the FT cast doubt on Russia’s official economic data. The new evidence that inspired Sandbu’s piece came from the Substack of Craig Kennedy. Kennedy produces data showing a surge in corporate borrowing in Russia, much of which takes the form of “policy loans” at subsidized rates, which are being used as a backdoor for war-financing.

Though this helps to keep war expenditure off the government balance sheet, its impact on the Russian economy is all too real. In particular, credit-fueled war-demand explains the stubbornly high inflation rate and “crowds out” other types of borrowing and investment. At the same time, it piles up mountains of underperforming debts, which at some point will become a recipe for financial instability and bank runs.

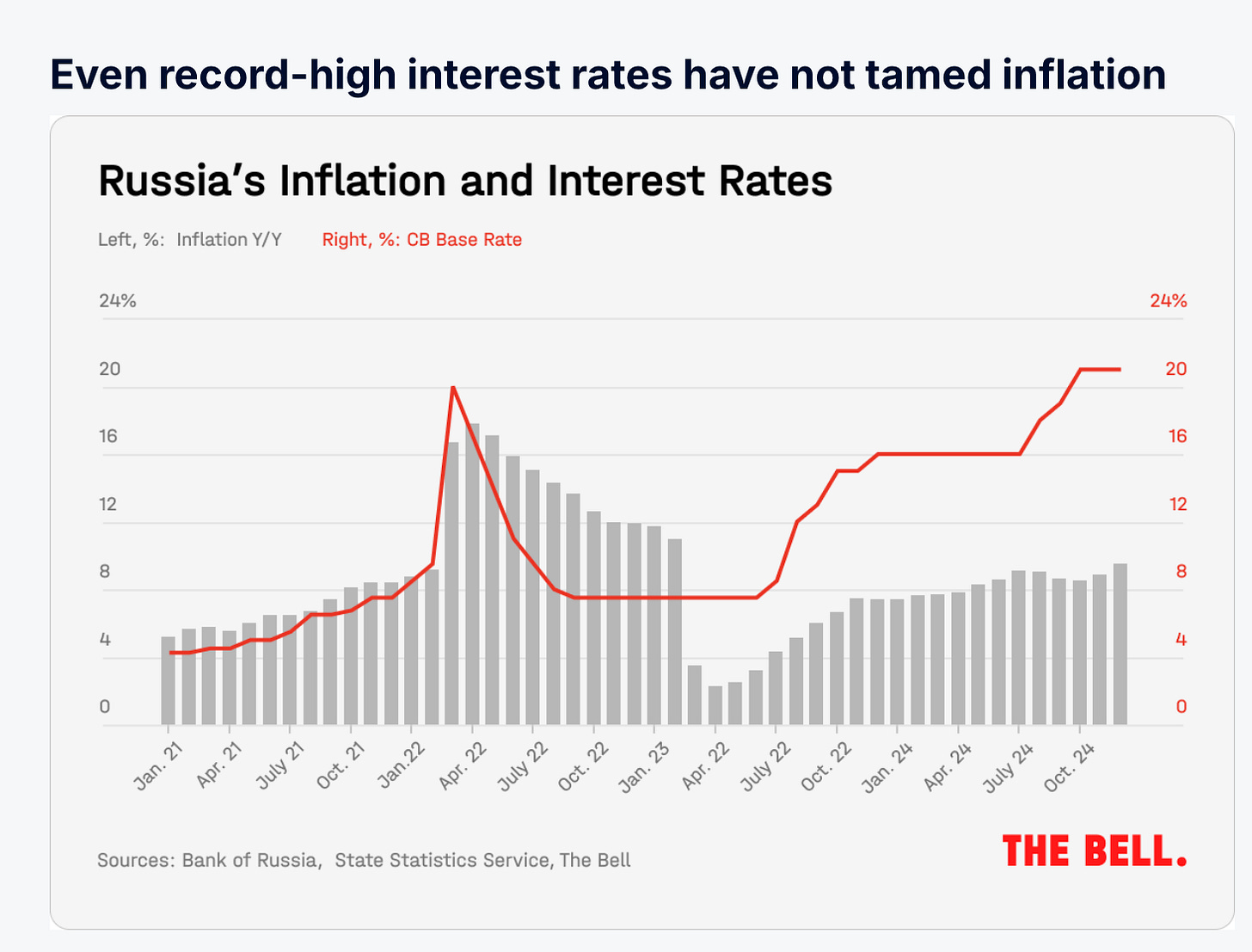

How big is this pressure? According to official data, inflation in Russia is currently running at 8 percent. Unofficial estimate put the figure far higher than that. The fact that the central bank has seen it necessary to raise rates to 21 percent suggests that they think the problem is more serious than the official figures suggest.

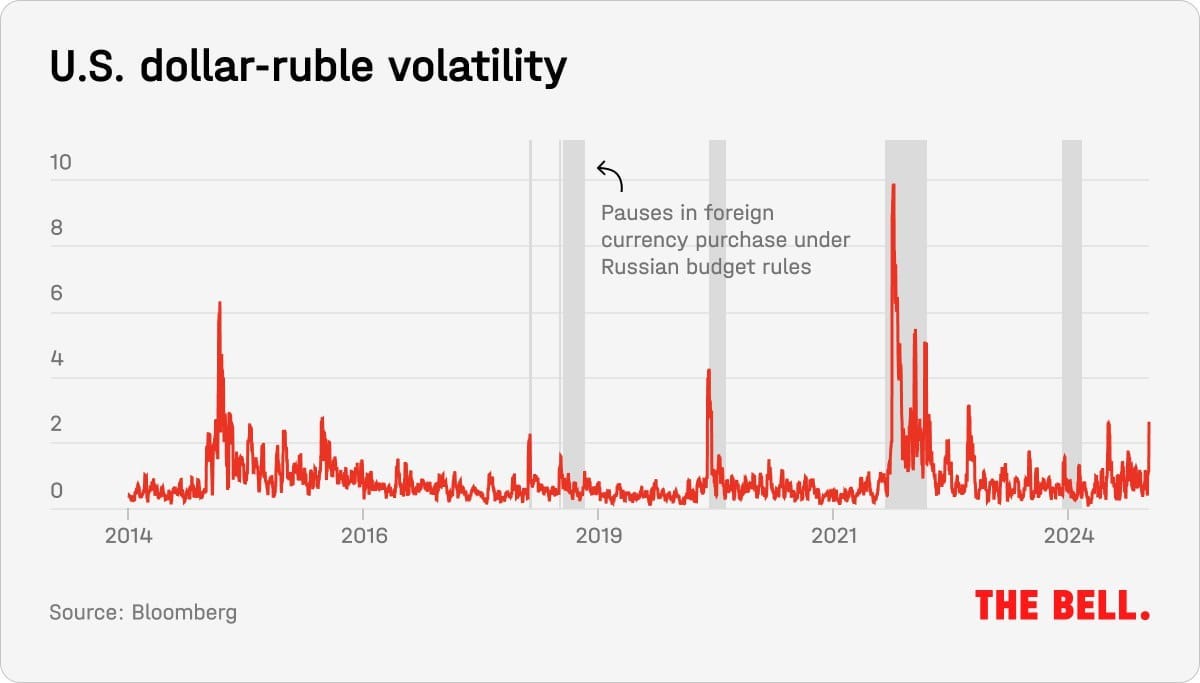

The market for foreign exchange is another indicator of financial anxiety. At the end of 2024, following a new round of sanctions, the rouble suffered a bout of weakness on foreign exchange markets. And as Alexandra Prokopenko and Alexander Kolyandr at the Bell comment, “The Kremlin has few options to prop up the Russian currency”

Western sanctions alongside demand outstripping supply are weakening the ruble. In the last week of November, the Russian currency experienced a dramatic collapse, down almost 25% from summer highs. The authorities don’t have many tools to tackle this problem: half of Russia’s gold reserves are frozen by sanctions, and the rest might well be needed to fend off threats to financial stability. The National Welfare Fund contains relatively little in the way of liquid assets. Without non-residents, who have largely exited Russian currency markets, and the free movement of capital (this has been restricted since 2023) interest rates are no longer an effective tool to stabilize the currency.

As a result, they conclude: “Ruble volatility is the new normal”.

Add all these factors together - depreciating currency, high inflation, even higher interest rates, mounting bad debts - and you can easily paint the picture of a war economy under stress, plagued by excess demands and the risk of financial instability.

The narrative of a house of cards waiting to fall does not require evidence of specific weakness ahead of time. Almost by definition, financial crises tend to explode as if “out of nowhere”. If we knew where they would strike, we would take preventive action ahead of time. As Kennedy comments:

Unlike the slow-burn risk of inflation, credit event risk—such as corporate and bank bailouts—is seismic in nature: it has the potential to materialize suddenly, unpredictably and with significant disruptive force, especially if it becomes contagious. … Moscow greater concern is likely Russia’s deteriorating credit environment could unleash events that dispel the widespread misperception—artfully promoted by Moscow—that Russia’s war finances are sustainable and face no significant risks. That misperception provides Moscow with valuable leverage in prospective negotiations. … Moscow now faces a dilemma: the longer it puts off a ceasefire, the greater the risk that credit events uncontrollably arise and weaken Moscow’s negotiating leverage.

But how serious is this risk really? It is certainly unpredictable. But by the same token, if the threat is of a sudden “credit event risk”, this is something that can be contained by decisive action by the monetary authorities, as the US monetary authorities have demonstrated in recent years. The West can certainly increase the risk of something breaking and can make it more difficult for Moscow to contain the fallout. The very act of pointing to Russia’s vulnerability of declaring its war economy to be a house of cards is performative. It helps to undermine confidence. Both Kennedy and Sandbu are frank about their political intent in this regard. Their aim is to call Russia’s bluff, to urge sanctions and to strengthen Ukraine’s bargaining position.

This is all very well, but it should not be confused with realistic analysis of Russia’s economic and financial situation. To judge the long run sustainability of the war effort the real issue is not the risk of financial crises, but the question of the underlying strength, or lack of it, of the Russian economy. This is the question that has been asked again and again since 2022. It remains frustratingly hard to pin down.

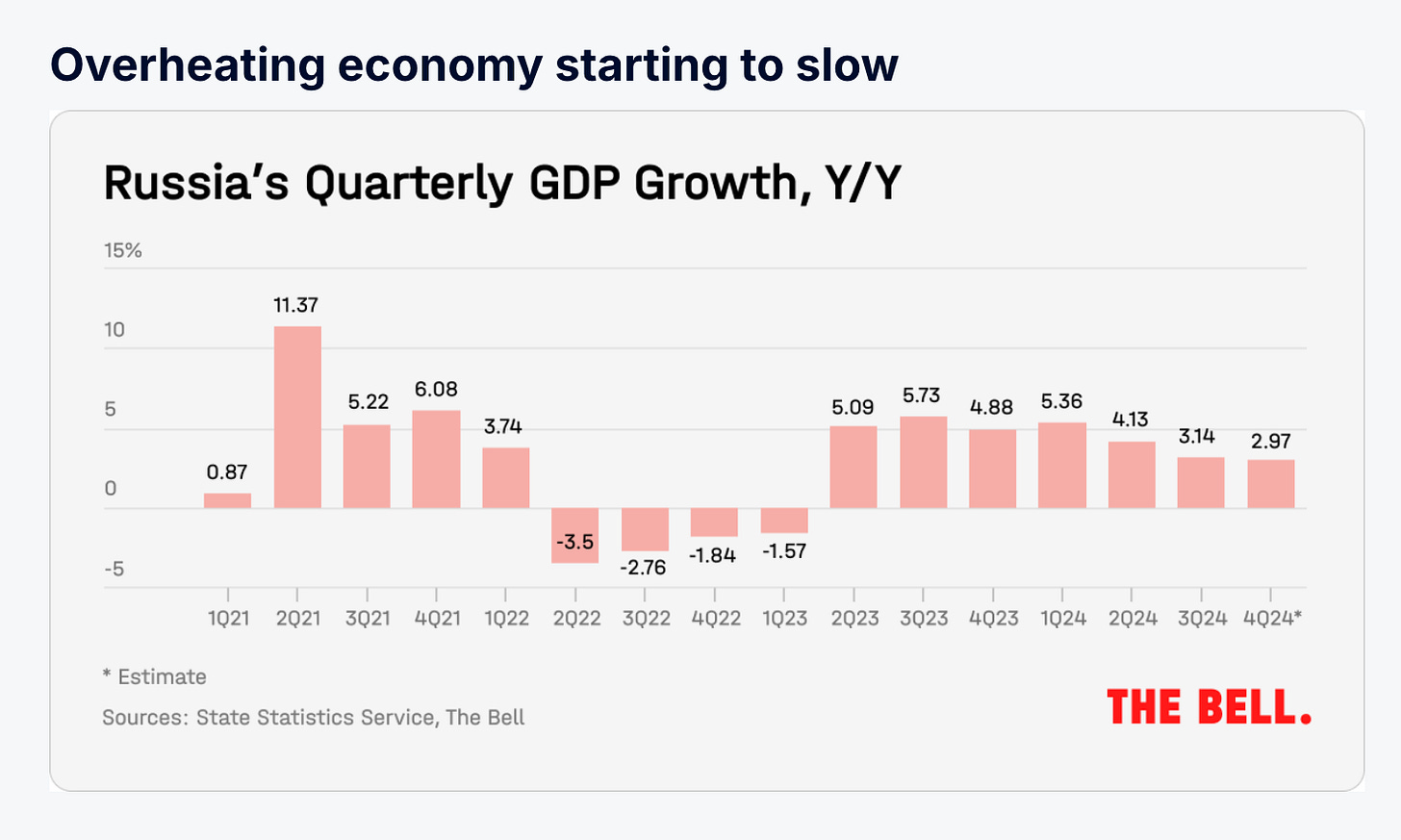

It is now commonly agreed that Russia reacted to the shock of war and sanctions with a Keynesian war economy. The possibility was raised by this newsletter as early as March 3 2022. Russia’s war Keynesianism has proven particularly effective, because of the chronic underutilization of the Russian economy in the 2010s. An export-focused policy centered on domestic austerity, had starved the Russian domestic economy of effective demand. In 2022 everything changed. The surge in domestic demand triggered by the war unleashed rapid growth in 2023 and 2024.

This has been fueled by Russian state spending in which defense plays an ever larger role. At 8 percent the defense budget remains surprisingly small relative to GDP. If Russia was really maintaining its current level of military activity on such a small share of GDP it would, frankly, be rather disconcerting. Rather than a damning revelation, it is to a degree “reassuring” to learn from Kennedy and Sandbu that actual military spending is well in excess of the modest official figures. It stands to reason that a substantial part of additional spending must be being financed off balance sheet. That isn’t surprising. It is exactly what one would expect in any well-managed wartime mobilization. The financial burden of the war is being spread across public, private and quasi-public balance sheets.

The impact on the Russian economy is to drive, lop-sided growth in manufacturing. As one report points out:

The results of these investments are striking. Russia has doubled its production of armored vehicles and increased ammunition output fivefold at certain facilities. A new sector—mass production of military drones—has emerged, while funding for civilian drone programs has been slashed tenfold. A significant portion of this budget supports Russia’s burgeoning force of contract soldiers. With the army requiring 20,000 to 30,000 new recruits monthly, the Kremlin relies heavily on financial incentives to attract men to the front. Average enlistment bonuses, supplemented by regional allowances, now stand at 1.1 million rubles ($11,000), with annual incomes ranging from 3.5 million to 5.5 million rubles ($34,000–53,000), depending on region and unit. These payouts place a heavy burden on regional budgets, with bonuses reaching as high as 2 million rubles ($19,000) in Moscow and 3 million rubles ($29,000) in the Belgorod region on the border with Ukraine. Such inflated sums reflect the shrinking pool of willing recruits, which is forcing authorities to offer additional incentives, such as debt forgiveness, university admission perks, and healthcare benefits for soldiers’ families. Direct federal spending on new recruits alone is estimated at 1.6–2.4 trillion rubles ($16–23 billion), not including additional costs for wounded soldiers and compensation for families of the deceased—figures obscured by classified statistics.

This is the fiscal arithmetic of what Vladislav Inozemtsev in 2023 dubbed Deathonomics. It places a heavy burden on public budgets. But that spending does not disappear into thin air. It flows back into the war economy and it ultimately serves to generate new flows of income for the state, in the form of taxes. According to the forecasts for 2025, tax revenues are expected to rise 73 percent.

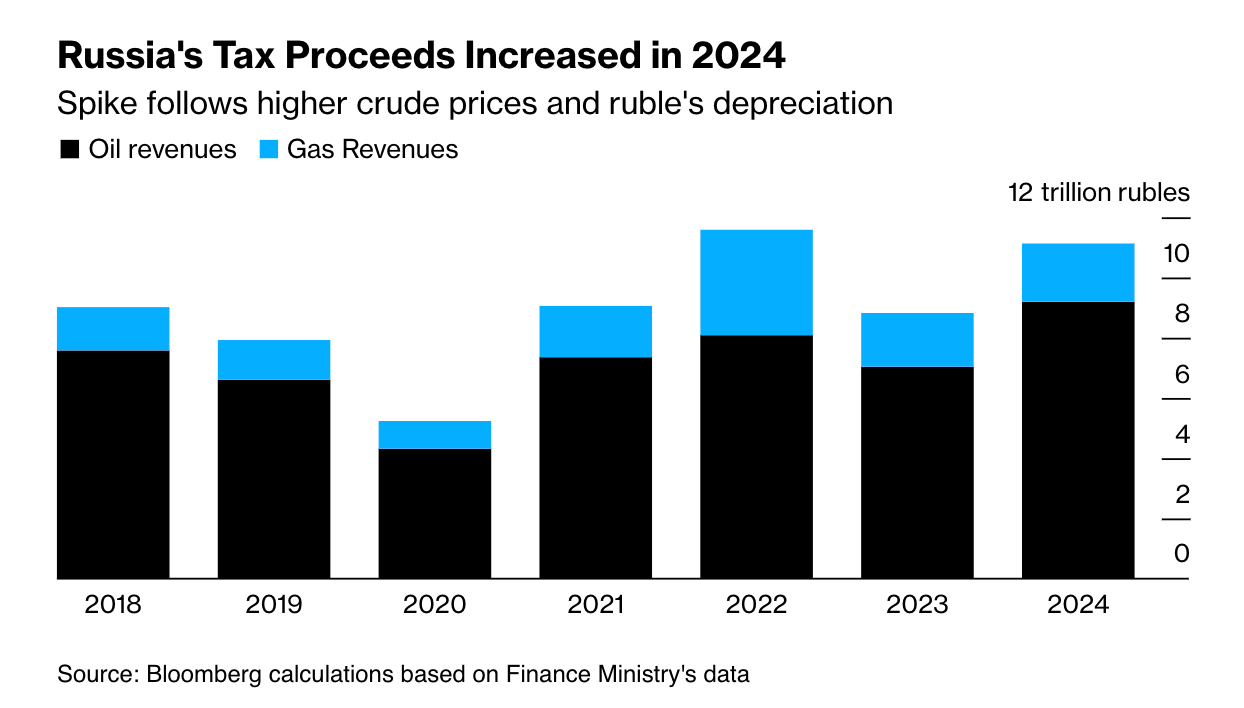

It helps that Russia’s energy revenues from exports have been buoyant. As Bloomberg reports: “Russia’s oil proceeds to the state budget increased by almost a third last year to the highest since at least 2018, spurred by higher crude prices as the nation adapted to international sanctions.”

Source: Bloomberg

Moscow controls its own tax rate. But, clearly, Western sanctions have not been doing their most fundamental job of financially constraining the Russian war machine. This is not to say that they have no impact. But the fact that oil tax revenues (which are four times larger than gas revenues) were larger in 2024 than at any time since 2018 is a stark indication of the lack of real determination on the Western side to shut Russia out of the global energy economy.

Unsurprisingly, the drain of the military draft and the rebalancing of the Russian economy generates significant pressures in the labour market. Far from any stagflation scenario, Russia is at full employment, with an unemployment rate of 2.3 % and a need for 1.6 million additional workers. The Russian economy continues to run hot. If there is inflation, it is in large part driven by surging nominal wage growth. As one report has it: “The Kurgan region, home to Russia’s sole producer of armored personnel carriers, has seen salaries jump by 33 percent. The Volga and Ural regions, hubs for defense manufacturing, are close behind.”

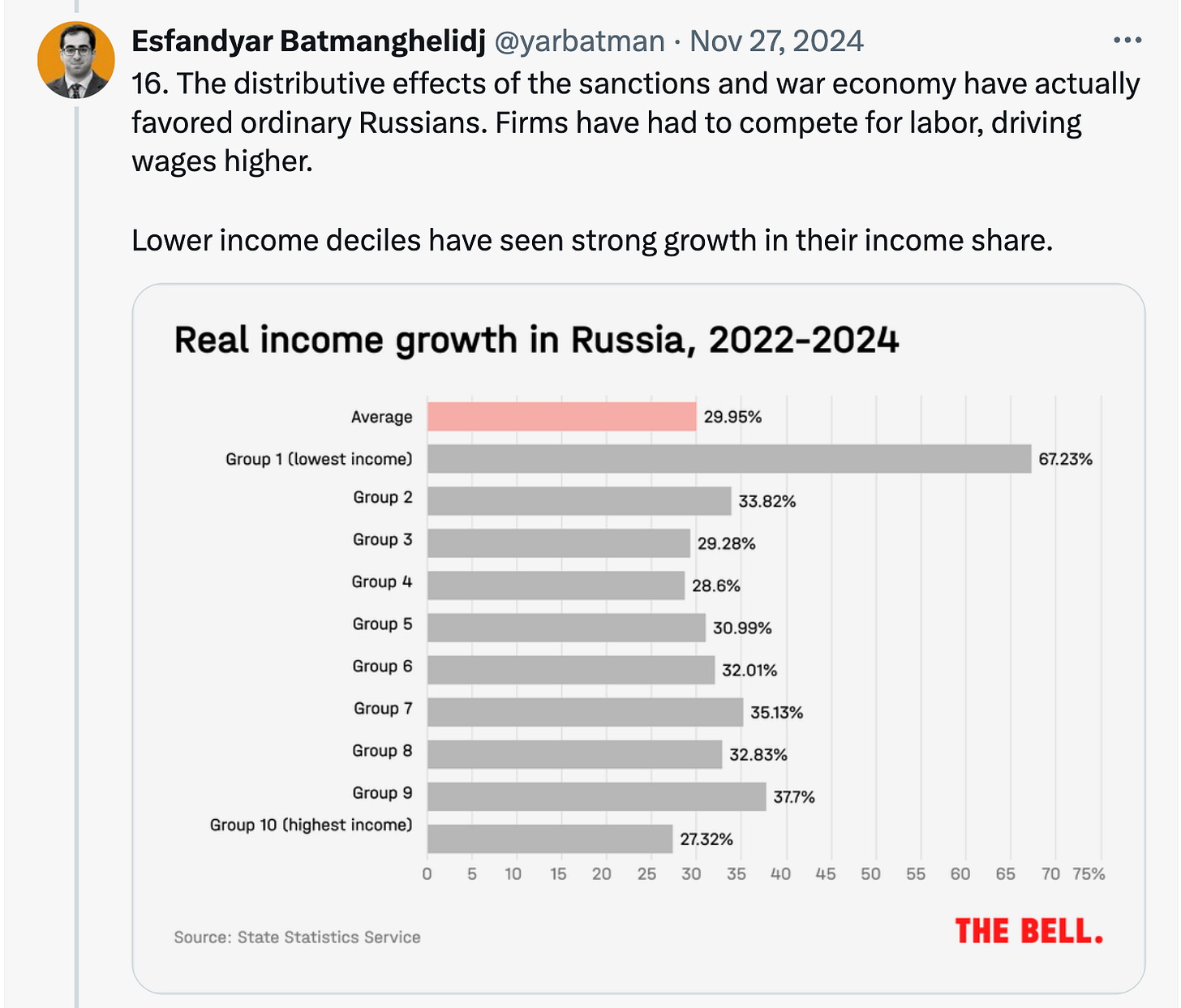

Rapid wage growth offsets inflation, leaving Russian households better off. And it is not just workers who are benefiting. As a leading expert on economic sanctions points out, the remarkable fact is that Russian households in the bottom 10 percent of the income distribution - presumably not highly skilled industrial workers - have seen their real incomes increase by almost two thirds since 2022.

Perhaps unsurprisingly: “Surveys indicate growing perceptions of a fairer distribution of income, with over 40 percent of respondents openly rejecting the need for personal freedoms or human rights, instead equating dignity with state-provided salaries and pensions.”

The real question is whether this war-driven growth model can be sustained and what its costs are?

Alexandra Prokopenko writing for Carnegie Politika argues that it “cannot address the chronic problems that have long plagued the Russian economy. We are witnessing an irreversible turn toward economic stagnation.” She points to the slowdown in growth in the defense industries, and the fact that:

Other sectors are faltering: extractive industries face declining production due to lower hydrocarbon export prices and OPEC+ production cuts, while agriculture has also lost momentum. Retail trade remains a rare bright spot, buoyed by consumer spending. However, surveys point to slowing business activity and rising inflation expectations among both businesses and households. … Falling global prices for coal and metals, combined with sanctions, have plunged the coal sector into real losses for the first time since 2020. This sector employs 650,000 people across thirty-one single-industry towns, where the shutdown of a single enterprise can paralyze an entire community, making its members prime candidates for government support. But other struggling industries—automotive manufacturing, non-food retail, and housing construction—are also lining up for state assistance. Resources are stretched thin as stagnant oil and gas revenues, coupled with energy sanctions, limit budgetary inflows. While tax revenues have temporarily offset falling hydrocarbon income, they are consumed by current expenditures, leaving no surplus. By November 2024, the liquid portion of the National Wealth Fund stood at just $31 billion, its lowest level since the fund’s inception in 2008. That reserve is insufficient to meet growing demand.

Interestingly Prokopenko points out that whereas manufacturing workers and welfare recipients may be doing well the same cannot be said for all constituencies.

The greatest losers in this overheated economy are Putin’s core supporters: public sector workers, including teachers, doctors, law enforcement personnel, and pensioners. Their wages and benefits are tied to official inflation rates of 9 percent, but real inflation for many households exceeds 20 percent. Meanwhile, the central bank has delayed its target of returning inflation to 4 percent, pushing it back to mid-2026 as Kremlin spending priorities crowd out monetary policy objectives.

These are immediate pressures that might conceivably impact decision-making. But as Prokopenko herself acknowledges: “A sudden collapse akin to the 1990s is unlikely: the government still has the resources to maintain a minimum level of order and control. … In Putin’s Russia, administrative costs for implementing policy decisions are remarkably low. Without public debate or opposition, the government can impose new taxes on individuals and businesses with minimal resistance. The public does not protest, and lawmakers in the State Duma vote as instructed. Major resource companies have already been subjected to extraordinary profit levies, such as Gazprom in 2022 and Transneft in 2024. Fertilizer producers, still active in global markets and largely untouched by sanctions, are likely next in line. Consensus within the government’s economic bloc is not required; Putin alone determines the course of action.”

This is not a system of government that is particularly vulnerable to the kind of crisis that Kennedy and Sandbu predict. After all, we know how effectively Putin’s power apparatus dealt with the shock of the 2008 financial crisis. The Kremlin orchestrated a ruthlessly effective stabilization effort. Faced with the far smaller financial risks of 2025, why doubt that it could repeat that tour de force.

The weaknesses that Prokopenko identifies in her analysis pertain not so much to crisis-management as long-run growth. “The structure of Russia’s market economy is steadily losing its flexibility under the weight of war and a centralized decisionmaking system that prioritizes control over dynamism. Subsidized sectors of the economy, insulated from interest rate fluctuations, are expanding rapidly. Beyond the military-industrial complex and its affiliates, preferential loans now underpin agriculture and real estate development as well. … Simultaneously, the Kremlin and the government are embracing a dirigiste approach to fiscal and monetary policy, increasingly dictating economic outcomes from above. … The proliferation of emergency measures disrupts conventional management practices. Ad hoc decisions are becoming the norm, even in areas where institutional solutions could suffice.. … ”

All this may be true. And it certainly goes against conventional institutionalist prescriptions for long-run economic growth. But this too is hardly the kind of immediate threat to Putin’s regime that would warrant describing the Russian war economy as a “house of cards”.

A more convincing analysis of Russia’s immediate situation comes from Vladislav Inozemtsev writing in the Riddle under the title of “In the kingdom of economic paradoxes”.

As 2024 comes to an end, Russia is experiencing one of the most intense bouts of economic hysteria since the first weeks of the war in Ukraine, when the collapse of ‘Putinomics’ seemed inevitable to many. After two years of growth fuelled by massive injections of money into the military-industrial complex, the creation of a well-paid army of mercenaries, significant deregulation of foreign trade and adept sanctions evasion, the economy is still facing visible challenges: accelerating inflation, declining investment and a slump in the construction sector. The government has been forced to raise taxes to balance the 2025 budget, but the most alarming symptom is the rapid increase in the Bank of Russia’s key interest rate, which recently hit a record level of 21% and is likely to climb even further by year-end. Dozens of commentators point out the stark gap between this rate and the inflation rate, arguing that such levels simply leave little room for economic growth. … criticism of the Bank of Russia now comes not only from independent and opposition-minded authors, but also from the system insiders. Consider the emotional speeches by Sergey Chemezov, the head of Rostec; the complaints of the leaders of the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP) demanding that the Bank of Russia should coordinate monetary policy with the government, and even warnings from the Centre for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting (CMASF) about a potential recession. The same group of ‘pragmatic managers’ has long criticised the Central Bank’s credit policies for hampering industrial growth and the government for hoarding excessive reserves.

But how seriously should one take such protests? As Inozemtsev points out:

It is hard to believe Chemezov’s claims that the defence industry is on the brink of profitability or that the Ministry of Finance provides only modest advances for the production of armaments … , while other funds have to be borrowed. Meanwhile, the Bank of Russia has recently released a detailed study estimating the share of interest payments in production costs at 3−3.5% (this is based on 2023 data, which means that the figure may have reached 4.5% considering the rising interest rate).

That is hardly the stuff of a serious profit squeeze. Furthermore, as Inozemtsev points out, whether an interest rate of 21 percent is excessive depends on what you think the inflation rate is. If you hold the popular opinion that Russia’s official data understate inflation by a large margin, then 21 percent may actually be the right rate. If you take the official rate as gospel then there can be little doubt that such a draconian rate will do the job of bringing inflation down.

What cannot be disputed Inozemtsev agrees is that the Russian economy is under pressure from high rates and rising inflation. Housing demand has fallen. Business profits are under pressure. The growth rate is likely to fall to 1.5 percent or less. But this is a slow down rather than a crisis.

Tax collection remains robust; the most pessimistic forecasts about declining export revenues have not yet materialised; and the ‘deathonomics‘ model continues to work. Moreover, if active hostilities in Ukraine cease or freeze in the coming year, this will undoubtedly increase the resilience of the Russian economy and (albeit less significantly) reduce the level of military spending. As we noted in a report co‑authored with S. Aleksashenko and D. Nekrasov, Russia has now sufficient economic resources to sustain the current course for at least another three years, which is why I am far from catastrophising. Dimitri Nekrasov’s calculations about Brazil’s economic performance in the 2000s, alongside nearly everything we know about the Russian economic system in the same period, suggest that an economy can operate under high real interest rates for many years if expectations are positive and/or there is substantial budgetary stimulus. That said, now is undoubtedly a good time to consider measures that can be undertaken to counteract the negative trends seen in recent months. … I have recently argued that the period from autumn 2024 to summer 2025 will serve as a ‘second adjustment’ phase for the Russian economy, somewhat resembling the period of adaptation to the new realities in the spring and summer of 2022. To navigate the current stage successfully, unconventional measures and approaches will almost certainly be required—from the Bank of Russia, the government and the Ministry of Finance.

Inozemtsev goes on to argue that inflation in Russia today is “not purely monetary in nature”. The growth rate in monetary aggregates has been brought under control since 2023. “The issue lies more in rising cost pressures from government-authorised increases in utility tariffs (natural monopolies), higher taxes, the effect of the appreciation of major currencies against the rouble, rising logistics costs, and increased commissions for international transactions … ". The obvious answer is for Moscow to apply direct controls on prices and to tighten antimonopoly legislation. Will this shrink corporate profits? Might it depress private investment? Yes it will. But that “is precisely the additional demand squeeze that the Bank of Russia is already seeking through higher rates”. He also advocates for financial repression in the form of interest rate caps to curb inflows of cash deposits into the financial system. Such measures would most likely affect only the richest Russian households.

As Inozemtsev concludes:

In any scenario, however, we do not foresee inflation accelerating to above 20% year-on-year, nor do we consider the business credit burden to be incompatible with economic growth over the next one or two years. Beyond this timeframe, either the government and the Bank of Russia will be forced to intervene more actively in the current situation, or the economy will find a new equilibrium, particularly if external conditions change significantly.

In an appreciative reply to Inozemtsev in early January Yakov Feygin insists that “we can’t dismiss the seriousness of Russia’s economic impasse”. He argues that the “distributional logic of a war economy under pressure — the political economy that undergirds its winners and losers — may give the Kremlin less cushion to adjust than it had in 2022.” But as Feygin concludes: “The empirical question is just how much capacity Russia has to spare to put off these choices or introduce them slowly enough to avoid a massive political shock. This question is very hard to answer. When the war began, many had hoped that sanctions would quickly collapse the Russian economy. Instead, Russia’s economy grew as wartime spending raised incomes and supercharged Russia’s consumer. High energy prices and years of accumulating reserves meant that Russian economic officials could deftly handle the impact of higher transaction costs. Does that mean that past is prologue and Russia has hidden reserves of strength? Maybe. However, it might also mean something else about the longer course of the Russian economy: it has been operating below potential since 2014 … ”. Is that room for growth now used up? That is the central question for the coming years.

Faced with the prospects of negotiations, it may suit Western pundits to conjure up the specter of financial collapse in Russia. But, if we actually want to get a realistic assessment of Russia’s long-run power potential, images like a “House of Cards” are an indulgence. What we need to know is how Russia’s political economy is actually put together.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Being Russian and actually having recently been to Russia - my best analysis is that Russia and perception of Russia in the West is currently undergoing a mini version of what the West is undergoing itself and its perception of Ukraine conflict. Let me unpack. I firmly believe that Western actions in Ukraine, and its perception of Ukraine, are determined by internal Western matters, i.e. an interplay between Western economy, Western lobbying groups, and Western problems. Ukraine and perception of Ukraine is important only insofar they affect the above.

Now, current set up in Russia is such that a large portion of the economy and lobby groups attached to it are getting killed by high interest rates. It is a very real problem, obviously, but as the author points out, it's manageable. However, this situation is unbearable for those lobby groups, and they create an artificial reality/narrative, exactly the same way their counterparts on the West do with regards to Ukraine. And since this narrative plugs in seamlesly into what those Western counterparts NEED to hear in order to continue pushing their interests in Ukraine, it gets lifted wholesale out of Russian discourse and presented as something real in the Western discourse. It is not real, it is simulacrum squared, reality's cousin twice removed,

It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

Naturally, the same happens on the Russian side, when bits and pieces of Western narratives, created for internal purposes, fit current interests of this or that power group with control over some sort of media.

Sorry for the long winded post, I didn't intend for it to read as a piece out of a French philopher text.

Our foreign policy vis a vis Russia is characterized by a lack of understanding as to the size, wealth, and national character of Russia. (In that order.) This failure has been firmly entrenched here for over one hundred years. In our common American government perception Russia is a nasty little central European country like Hungary or Bulgaria. Decade after decade we miss he point. We got into Afghanistan because we failed to realize that when Russia met defeat there it was not due to any inherent weakness on Russia's part. Size does matter. We simply and mistakenly thought, "We can do better."