Chartbook 343 : Polycrisis & the critique of capitalocentrism.

A world at "loose ends" mini-series # 1.

2008 and the years that followed delivered a historic shock.

The vertiginous panic of the financial crisis, the protracted eurozone crisis that followed, the Occupy movement and the “inequality moment”, BLM, mounting anxiety about fascistoid politics, the radicalization of the climate crisis, escalating geopolitical tension, all this and more has led to a search for big, urgent, powerful frames of analysis. Anything less seems inadequate to the moment.

One of the responses on the progressive political side has been a return to what you might call classical foundations. For some this was Marxism. For others, myself included, it involved a return to Keynes, left Keynesianism and currents like MMT and the Green New Deal.

This turn was “necessary”. It has been intellectually and politically productive. But it also came at a price.

What I worry about is a double evasion of history, both “real” and intellectual, if such a distinction may be permitted:

a. In real terms: by anchoring critique in classical social theories that were shaped above all by the 1900-1950 moment, we risk underestimating the radicalism of the present. This is not to underestimate the dramas of the early 20th century - I hope I may be spared that accusation. But to insist on the novelty, unprecedented scale and pace of our current predicament. This is true in three dimensions:

the sheer scale and resources of modern economic growth and technology extending to billions of people and the huge power this confers on small groups of elites.

The new multipolar (nuclear) arms race.

The multifaceted and escalating environmental crisis.

The ecological crisis now must be the pace-setter and the paradigm of all other critical thinking. Taken together these three tendencies mark out our epoch as unprecedented.

b. In intellectual terms, by returning to the classical roots of critical social theory in the early 20th century, we “skip over” the often troubling and complex development of critical social thought between the 1960s and the early 2000s. To put it bluntly, there has been a retrogression in social theory.

For those of my generation, raised in the 1970s and 1980s, coming of age in the 1990s and 2000s, the shock of 2008 provoked a kind of rejuvenation. But it has also implied a break with our own intellectual genealogy. This covering-over is never complete. “You can take the boy out of the 1990s, but you can’t take the 1990s out of the boy”. The layering of historical phases has led to opacity and, at times, to inter-generational confusion.

As Barnaby Raine recently framed it, my intellectual formation in the post-Marxist 1980s and early 1990s has remained present, and yet tacitly so.

My PhD supervisor @adam_tooze belongs among varied intellectuals (Therborn, David Scott, Chakrabarty, Hall etc) seeking social theory after the collapse of dialectical History. I've long thought this is underplayed in his books, which are presented as narrative histories... /1 When I first read the 'Crashed' manuscript, for example, I said "I don't get what relationship you're tracing between economy and politics." Once he explained the Latourian logic, the refusal of those two conceptual bundles, the book made sense to me; but it didn't before. I wanted him to publish a reply to Perry Anderson, because I was struck that PA took the lack of a Marxist account of totality as evidence of a (politically motivated, anti-radical) refusal of any such account, which seemed to eclipse the interesting possibility: that in a world no longer structured by (mediations of) a fundamental class antagonism with immanent emancipatory content, we have to go back to the drawing board - philosophically *and* politically - to account for our present, and the proper response to it. Narrative history and Latour meet here. Both refuse any given theory of structure, against whose backdrop agents can then be read. I think Marxism could still be helpful in understanding the appeal of that choice: The crisis of a Marxist theory of social structure followed the disassembly of the emancipatory coalition of the defeated 1960s-70s world revolution. When the standpoint collapsed, so did the theory, which fits with Lukacs or Gramsci (minus their optimistic teleology). Like the four figures I mentioned above, Tooze was recruited to the revolutionary left when young and then attracted to a 1980s revisionism (Eurocommunism in his case) that claimed to speak to Brecht's 'bad new things' not the good old ones. These accounts - I find Scott's the richest - usually suppose that something was always missed by neat dialectical History (not least its usual Eurocentrism) but also that neoliberalism marks a rupture more fundamental than a 'forward march' halted, with its agents enduring. Clearly, these claims are contestable. But Anderson's difficulty is that he too has long suggested such an intellectual crisis for Marxism, from his famous 1976/83 book duo to his sensitive 90s essay on Fukuyama and then NLR relaunch essay in 2000. I think the hard question (my PhD question!) is whether some concept of freedom beyond relations of subordination can survive the end of History, the disassembly of freedom's assumed subjects. Tooze doesn't ask that, but answering it will require a rethought social theory. At stake here is both the scale of the historical rupture - what endures? - and its character: what is possible in new times? I think we require first the open investigation ('without guarantees') of processes of subject formation, the ground of political struggle and norms. If this all feels like the 90s replayed, my hope is that now we are trying to tell new stories (hence Tooze's triadic Foucault/Latour/Keynes amalgam) not just bemoan the death of old ones

In reaction to critics like Anderson and exchanges with comrades like Barnaby Raine, since 2020 I’ve appropriated the “found concept” of polycrisis from the foot-loose French thinker Edgar Morin as a way of highlighting this tension.

To the frustration of its many critics, the concept of polycrisis lacks the respectable intellectual genealogy and analytical guts that a good critical theorist would expect. To me, that is precisely why it seems right for our moment. In its lack of specification, the polycrisis concept serves as a reminder of the indeterminacy and uncertainty and complexity that we have lost amidst the bold new certainties of the “capitalocene”.

The idea that going back to the social theory of the post-Marxist moment of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s could actually be a mind-opening move is, admittedly, counter-intuitive. On the left that era is often seen as a moment of disorientation and closure. I am certainly not arguing for a simple historical appropriation. 2008 happened. We can no more go back to the future by way of the 1990s than we can by way of the 1930s. What I appreciate about the theorizing of the “before (2008) times” is its open-endedness. My wager is, that it is precisely that open-endedness that we need, to encompass the radicalism of our current moment.

In the interview with Ding Xiongfei of the Shanghai Review of Books, we discussed Bruno Latour and Ulrich Beck, two theorists who grappled with radical novelty, and who opened the conventional frame of social theory in so doing. For all their basic conceptual differences, they also shared a sense of the catastrophic potential of modernity, which in the late work of Latour became truly dramatic.

In subsequent posts in this mini-series - the reason for the choice of title will, I hope, become clear later in this post - I want to repeat this maneuver with regard to interpretations of globalization and globality offered in the 1990s and early 2000s by anthropologists Anna Tsing and Arjun Appadurai and historians Michael Geyer and Charles Bright. My hunch is that in revisiting their complex articulations of the first wave of post Cold War globalization, we may gain some new purchase on the present crisis.

In the Maeder lecture, which I had the privilege of giving at the New School in November last year, I returned to the polycrisis term and situated it in relation to the fundamental critique of capitalocentric versions of social theory offered by feminist anthropologist pairing, K Gibson-Graham in The End of Capitalism, (1996).

The video of the lecture is here.

The powerpoint for the talk, adapted for pdf format - I’ve tried to reproduce the animation of the slides through sequences of pdf gages - can be downloaded here.

The discussion after the lecture was spirited and left me feeling that the argument can perhaps best be crystallized as follows:

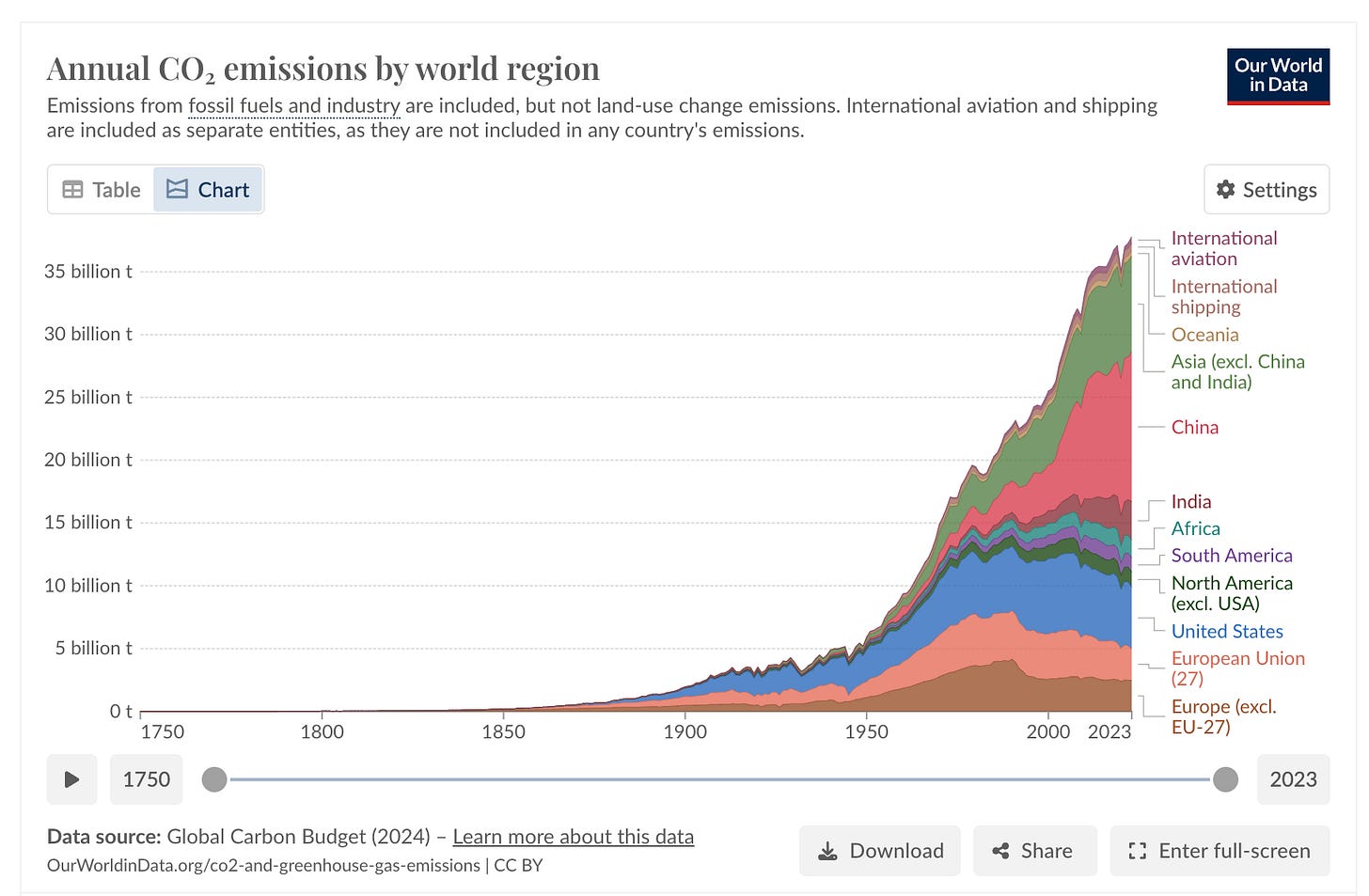

The central problem of the present is how to think the radical novelty of our situation. How far can conventional crisis theory do justice to our current moment? The ecological crisis now must be the pace-setter and the paradigm of all other critical thinking. We have to take seriously the implications of the graph that maps all of modern economic history in terms of CO2 emissions and unmistakably highlights the utter novelty and radicalism of our current moment.

To put it crudely, most of classical critical theory was formulated in the left-hand half of this graph which, as one can see with the naked eye, has little if any serious bearing on our current predicament. You could say that patterns of fossil capitalism were laid down in the 19th- and early 20th centuries, structures were established. But quantities matter. And the great global acceleration since World War II has turned quantity into quality.

What preoccupies me is Mark Blyth’s dramatic 2021 description of our current predicament: “climate breakdown … is a giant non-linear outcome generator with wicked convexities. In plain English, there is no mean, there is no average, there is no return to normal. It’s one way traffic into the unknown.” The essential question is this: Can critical social theory come to terms with this reality? “No mean, no average, no return to normal .. one way traffic into the unknown”?

After debating with Nancy Fraser and other New School colleagues, there are, as far as I can see, four different responses to this challenge:

1. The first is to insist that polycrisis is nothing new. It is just the latest form of the kind of crises that Marxists have always thought themselves good at analyzing. Some blend of Marx on the ecological rift, Gramsci and Polanyi with racial capitalism thrown into the mix, will do the trick. The underlying hypothesis underpinning this theoretical stretch from the 1920s, 1930s or 1940s into the present, is one of structural continuity. The Great Transformation that Polanyi diagnosed is still meaningful to us today. Gramsci’s idea of interregnum still illuminates our reality.

This seems to me to be a gamble at long odds and one that severely underestimates the radical break marked by the great acceleration since 1945. How is this kind of intellectual immobilism consistent with the protean and spectacular change that defines our moment? Nor do I see how it is consistent with the radical intellectual tradition, to which it declares its loyalty, a tradition, which from the late 19th century onwards was not rehearsing the classics, but was on the move, with Lenin as the great iconoclast.

2. A second position is that the term polycrisis does indeed indicate a new degree, complexity, intensity and urgency of problems. Theory must develop to face this. But, the outlines of this kind of new and more complex crisis theory were diagnosed at the latest in the 1960s and 1970s. This was the moment at which class conflict, accumulation crises on both sides of the Iron Curtain, anti-colonial struggles, struggles over identity, new challenges like environmentalism first converged. This is what Louis Althusser and Stuart Hall were pointing to with their conception of overdetermination.

In Gibson-Graham’s words: “Althusser's overdetermination can be variously (though not exhaustively) understood as signaling the irreducible specificity of every determination; the essential complexity - as opposed to the root simplicity - of every form of existence;7 the openness or incompleteness of every identity; the ultimate unfixity of every meaning; and the correlate possibility of conceiving an acentric - Althusser uses the term "decentered"8 - social totality that is not structured by the primacy of any social element or location.” Gibson-Graham “Capitalism and Anti-Essentialism” in the End of Capitalism, 27.

The current moment vindicates the theoretical prescience of Althusser and Hall from half a century ago. Now is an exciting moment to think with them and through them.

3. The third position admits that position 2 is easy to agree with. The agenda laid out by Althusser, Hall and others is attractive. As Gibson-Graham put it: "Althusser's concept of overdetermination can be seen as the site of a longing or desire - to resuscitate the suppressed, to make room for the absent, to see what is invisible, to account for what is unaccounted for, to experience what is forbidden.”

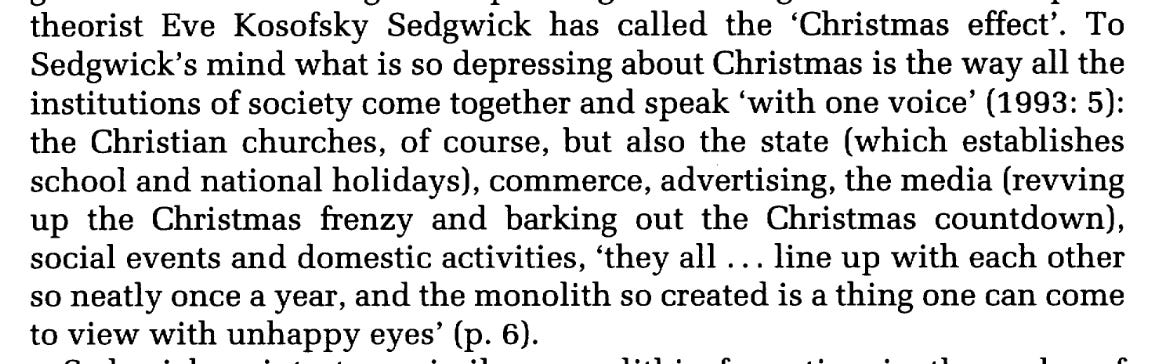

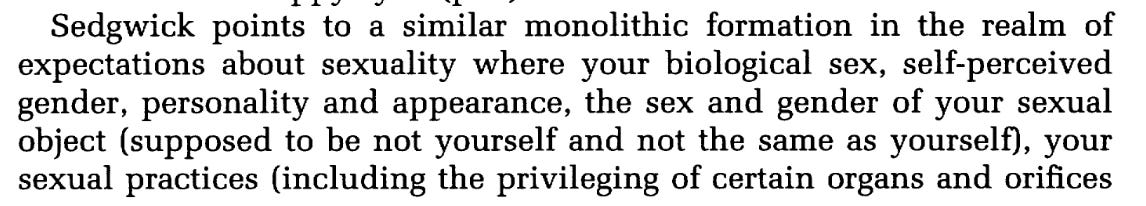

But it poses the question: Who has actually delivered on that agenda? As K Gibson-Graham show in the End of Capitalism, whilst pointing to overdetermination, actually producing an account in terms of overdetermination has proven elusive and more often than not analysis slides back into the simplicity of the first position. On their reading this isn’t accidental. Gibson-Graham drawing on queer theorists like Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick criticized the overly tight and coherent conception of reality implied by standard social theory. It is that underlying set of assumptions - ontological if we may be so bold - that repeatedly frustrate the intention of the analysts of overdetermination.

Gibson-Graham illustrate this with regard to Kosofsky Sedgwick’s so-called ‘Christmas effect”.

What would breaking this monolithic representation of power entail? It would involve a social theory which allowed meanings and institutions to be “at loose ends with each other”:

Gibson-Graham, J. K. (1996). Queer(y)ing Capitalist Organization. Organization, 3(4), 541-545.

I find Gibson-Graham’s critique of conventional social theory to be highly persuasive and illuminating. Since they wrote, the emergence of even more totalizing concepts, such as, for instance, the capitalocene, only demonstrates how relevant and urgent that critique remains.

If stabilizing an account of overdetermination is difficult in practice, then to keep those radical and unsettling possibilities in mind we need irritating ideas that provoke non-essentializing thoughts. This heuristic is the best justification, it seems to me, for evoking irritating and incomplete concepts like “polycrisis”.

Polycrisis is underspecified. It is a weak theory. But those who criticize that in the name of greater clarity or stronger theory underestimate the scale of the mess that we are in. Polycrisis is useful precisely because it reminds us of the knowledge crisis, the gap between inherited critical theory and the radicalism of our present.

This kind of thinking is necessarily going to feel provisional and mobile and unsatisfactory. This is precisely what one expect from non-essentializing accounts that cannot and don’t want to offer the certainty of resolution/conclusion/category etc. They are on the move, rootless and, to a degree, fugitive.

4. Where I feel we must move on from Gibson-Graham, however, is with regard to the underlying emplotment and diagnosis of the present.

For Gibson-Graham, writing in the late 1990s, their intention in introducing their radical critique of capitalocentric conceptions of political economy was to query power and to break the grip of hegemonic ideology. My proposition is less optimistic .

My suggestion is not so much that capitalocentric readings of modernity tend to lead us to underestimate the possibilities for radical agency, but that they tend to lead us to underestimate the scope for catastrophe. A world at loose ends with itself may have more degrees of freedom, but it also has novel and terrifying scope for crisis.

The escalation of the environmental crisis, the emergence of multi-polar great power competition (the escalation of regional conflicts articulated with the tripolar nuclear arms race) and the extraordinary acceleration of oligarchic wealth (Musk) create a novel situation with new catastrophic potential. This catastrophic potential might be thought of as impelled by the violence of “hyper agency”, the magnitude of environmental blowbacks (as witnessed for instance in the form of a pandemic), or the sheer meaningless of public discourse - an attrition that goes beyond ideology, which could, at least, be said to serve an instrumental purpose.

A world at “loose ends with itself” might be precisely the kind of conceptualization we need to grasp out current moment as “a giant non-linear outcome generator with wicked convexities. In plain English, there is no mean, there is no average, there is no return to normal. It’s one way traffic into the unknown.”

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Why do 'smart' people make it so difficult to understand their ideas? Too many references to other people and their theories and jargon here. Who is the intended audience? I feel it's not me

I'm just a retired English professor of very little brain. So I want to ask a stupid question. I get the possibility of catastrophe. What about the possibility of either muddling through or even a good outcome?