Chartbook 342 Are we all dead in the long run? John Maynard Keynes and the politics of time

Guest essay by Stefan Eich

Chartbook is delighted to publish this fascinating essay by political theorist Stefan Eich Georgetown.

“In the long run we are all dead.” Reduced to a slogan, John Maynard Keynes’s witticism has by now become an encapsulation of his entire thought. Not for nothing does the line serve as the title of Geoff Mann’s brilliant account of the politics of Keynesianism (on which more below). Curiously, the quote is often understood in quite different ways. Indeed, it often says more about those who wield it than about Keynes himself.

In particular among Keynes’s conservative critics it is, for example, often taken to imply a dismissive stance toward the future. This comes in a wide variety of flavours decrying a Keynesian bonfire of public spending and indebtedness in disregard of future generations, though not far below the surface there is usually a slur about Keynes’s sexuality and childlessness.

Inversely, the line has also been read not so much as an indulgence but as a call to action in the present. This is Keynes the saviour who asks us to focus on crises in the here and now. Even some of Keynes’s most sympathetic readers, including his biographer Robert Skidelsky, have at times endorsed a version of the corresponding claim that Keynes “cared little” about the long run. As Skidelsky put it in his celebrated biography: “Keynes’s indifference to the long run, is summed up in his famous remark: ‘In the long run we are all dead.’” (392)

It is not my goal to litigate the hopefully obvious point that Keynes cared about the future. Instead, I want to take Keynes’s misunderstood quip about the long run as a point of entry to explore his broader thought concerning the politics of time. The proverbial long run has become hotly contested terrain once more, not least in the context of climate politics where Keynesianism appears both as an embodiment of the Great Acceleration and—in the form of Green Keynesianism—as a saviour.

Let me begin with a seeming puzzle that emerges when we juxtapose to Keynes’s observation about the lifeless long run a much less familiar quote: “In the long run almost anything is possible,” Keynes wrote in 1942 in an article on “How Much Does Finance Matter?” for the BBC journal The Listener on the topic of postwar reconstruction. “Therefore do not be afraid of large and bold schemes. Let our plans be big, significant, but not hasty.” (Collected Writings [CW], Volume 27, 264-70) Not coincidentally, it was in the same piece that Keynes famously quipped that “Anything we can actually do we can afford.”

Placed alongside his more familiar pronouncement, this divergent statement about the endless possibilities of the long run appears to point toward a tension. It seems in any case fair to say that we still do not have a good understanding of how these two claims about the future fit together.

Zachary Carter, for example, ends his excellent twinned biography of Keynes and American Keynesianism by simply running the two lines together.

“Despite everything, we find ourselves back with Keynes—not merely because deficits can enable sustained growth, or because the rate of interest is determined by liquidity preference, but because we are here, now, with nowhere to go but the future. In the long run, we are all dead. But in the long run, almost anything is possible.” (534)

But how precisely should we understand the relation between these two pronouncements? After all, how can anything be possible in the long run if we are all dead? Did Keynes change his mind? Is there perhaps more than one long run? And who are “we” anyway?

Anxiety and Hope

One of the most interesting readings of Keynes’s attitude toward the long run has recently been sketched by Geoff Mann in his account of “Keynesianism” as a distinct liberal politics of saving civilization (see also Adam Tooze, “Tempestuous Seasons,” LRB, September 2018 and “Framing Crashed (6): The Politics of Keynesianism”).

“The key,” Mann summarizes, “is to understand the relation between bliss and disaster.” (15) Keynesianism is from this perspective characterized by a peculiar combination of “existential terror” and “boundless optimism” (14, 16). As Mann perceptively points out, it is precisely the apparently infinite potential of civilization that fuels terror over its possible collapse, giving rise to a liberal dialectic of anxiety and hope.

This coexistence of fear and anticipation expresses itself most concretely in a relentless focus on whatever crisis presents itself in the present. As Mann explains:

“[O]ne might even say of liberal capitalism that if in the long run it’s dead, in the short run it is Keynesian. The Keynesian return in the moment of liberal-capitalist crisis is thus axiomatic, since it is a Keynesian sensibility that recognizes and names the crisis per se, that is, a conjuncture or condition that by definition cannot go unaddressed. (25-6)

This is a brilliant and powerful reading of the spirit of Keynesianism. In turning from Keynes to Keynesianism, Mann intentionally shifts the underlying question away from uncertainty to anxiety, from temporality to psychology. This attention to the affective imagination of political economy is a productive feature of Mann’s dissection of the Keynesian mind, its faith in rationality and its simultaneous dark fears—a diagnosis that productively draws on Raymond Williams’s concept of “structures of feeling”.

Keynes himself was of course deeply interested in psychology and especially Freud, who left a deep imprint in his economic thought, as Jon Levy also shows in his forthcoming book. And yet, psychology is not the only way—and perhaps in this context not the most productive way—to frame what I want to consider instead through the lens of temporality.

Expedience and Temporal Sacrifice

Behind the long run quote looms Keynes’s long-standing engagement with the thought of Edmund Burke.

Keynes’s interest in Burke ran deep. He not only arrived at King’s College as the proud owner of the complete works of Burke but at a debating contest in Cambridge he appears to have read Burke’s speech on the East India Bill in full period costume.

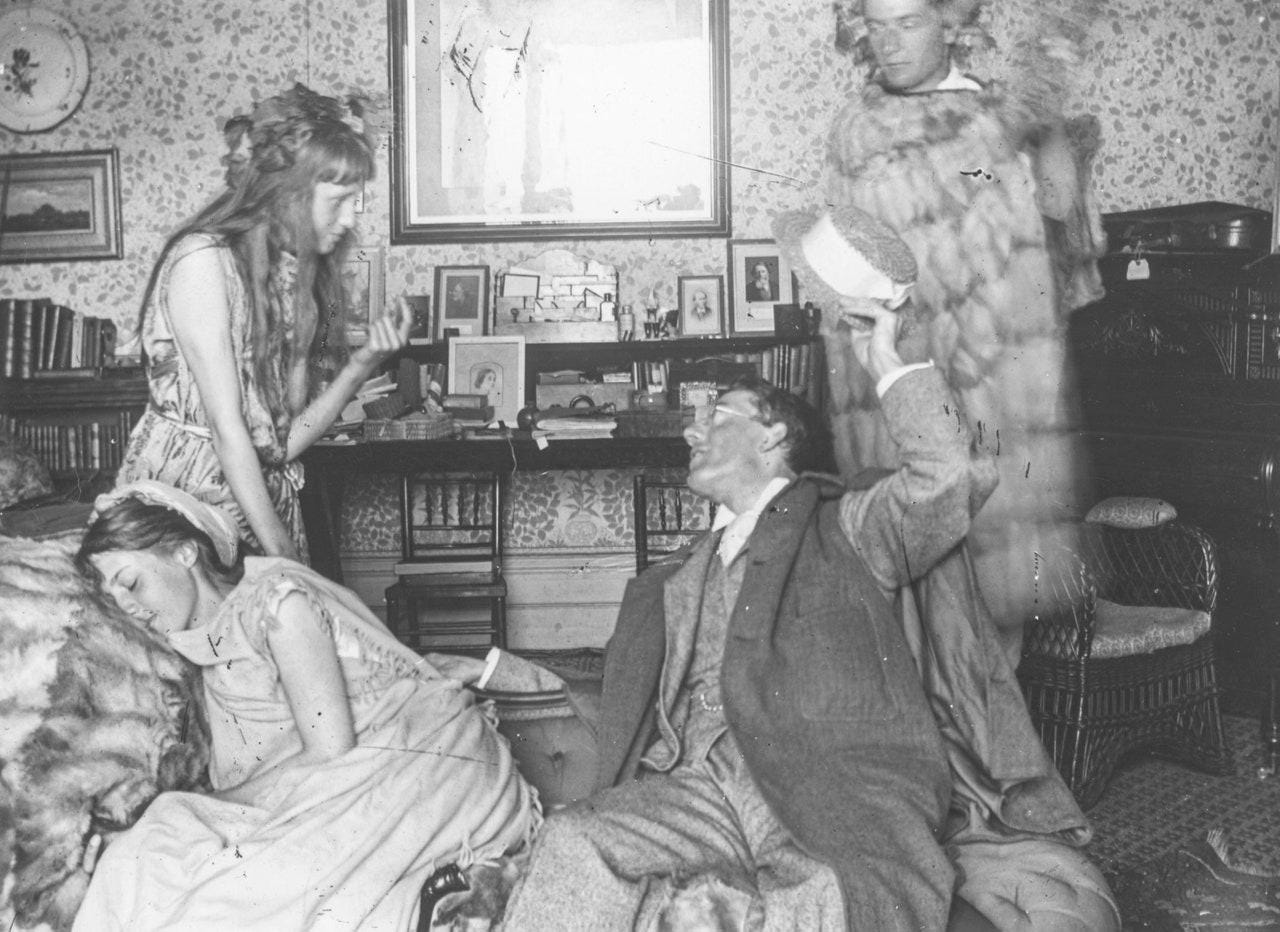

Keynes (right) in 1903 in Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s comedic play “The Rivals” at the University of Cambridge, Source: World History Archive.

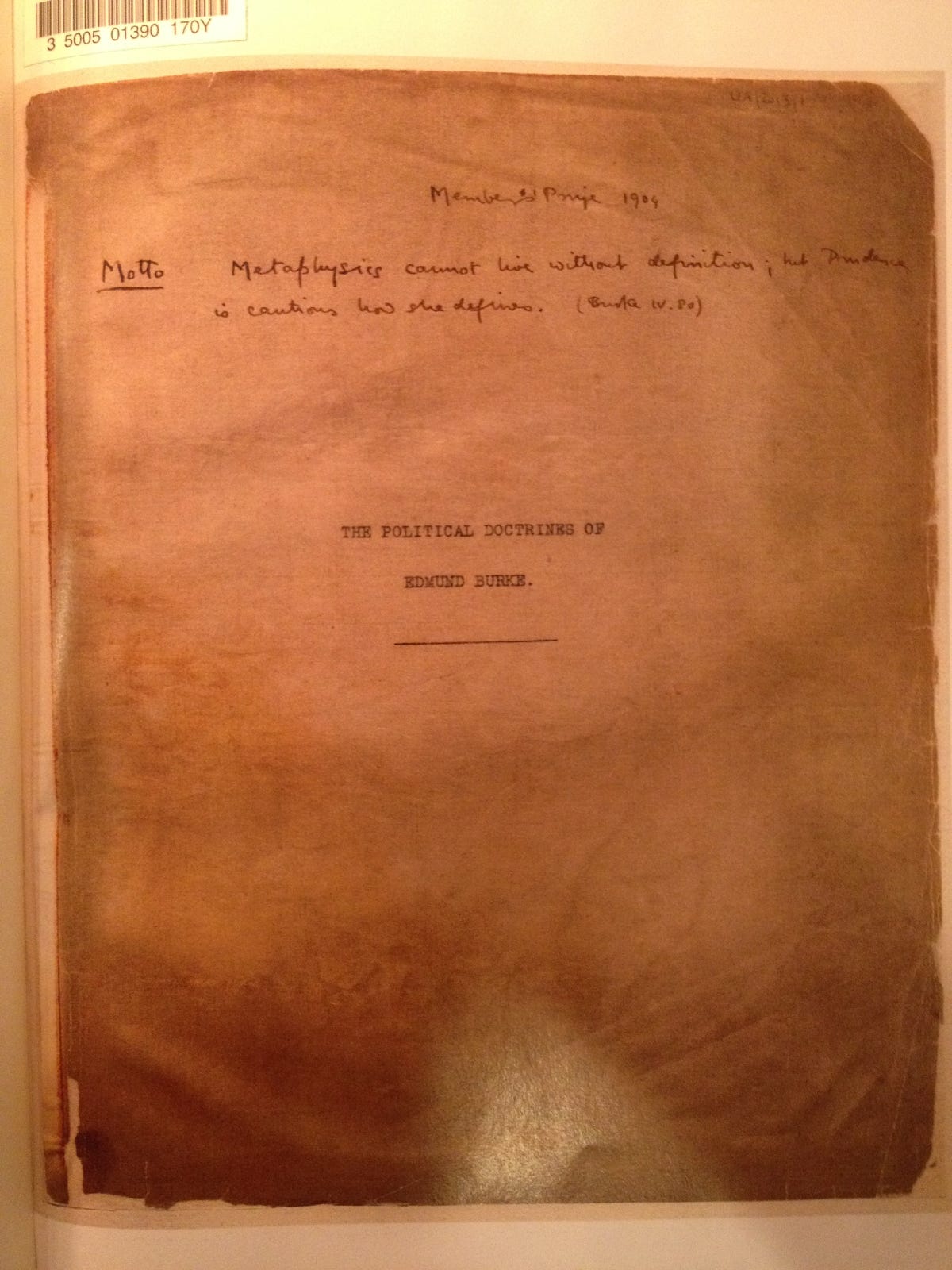

The most concrete product of Keynes’s intellectual encounter with Burke was a hundred-page essay on “The Political Doctrines of Edmund Burke” (1904), which, inexplicably, remains unpublished to this day. (I’m currently working on a blue book for the Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought that will rectify this by collecting Keynes’s political writings.)

John Maynard Keynes, “The Political Doctrines of Edmund Burke” (1904).

Source: John Maynard Keynes Papers, King’s College, Cambridge.

In the essay Keynes offered a synthesis of Burke’s thought that revealed a “consistent and coherent body of political theory” behind his seemingly shifting political positions. Keynes’s essay was written in an airy style, indebted to the Whig MP himself, that would later also distinguish many of Keynes’s own essays. It mixed candid admiration with forceful critique as it set out to reconstruct Burke’s philosophical and political principles in light of their changing contexts and applications.

What above all appealed to Keynes was Burke’s view of politics as a means for the realization of higher goals. Concretely, that translated into a pronounced emphasis on expediency or expedience—Keynes himself alternated between the two spellings in his essay. “In the maxims and precepts of the art of government,” Keynes summarized what he took to be a major strand of Burke’s politics, “expedience must reign supreme.”

Crucially, arising from this philosophical appreciation for political expedience was a profound skepticism toward the suggestion that present harm, in whatever form, could ever justify uncertain future gain. Referring to Burke’s argument in his Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs (1791), Keynes explained that Burke “is continually insisting that it is the paramount duty of governments and of politicians to secure the well-being of the community under their care in the present, and not to run risks overmuch for the future; it is not their function, because they are not competent to perform it.”

Burke’s “timidity in introducing present evil for the sake of future benefits,” Keynes agreed, was a principle that stood in great need of emphasis. “Our power of prediction is so slight, our knowledge of remote consequences so uncertain that it is seldom wise to sacrifice a present benefit for a doubtful advantage in the future.” It was consequently rarely right to sacrifice the well-being of the present generation for the sake of a supposed millennium in the remote future.

Two deeper principles stood behind this cautioning against intertemporal sacrifices.

First, and most fundamentally, any future outcome was simply uncertain and any attempt to procure progress through sacrificial means incurred a substantial risk. The cautioning against intertemporal trade-off was thus not driven by the claim that future generations mattered less in moral terms but rather by the inherent unpredictability of the future. It was simply the case that, as Keynes summarized, “we can never know enough to make the chance worth taking.”

Second, and closely related, there was the cost of transition. As Keynes put it, it was “not sufficient that the state of affair which we seek to promote should be better than the state which preceded it; it must be sufficiently better to make up for the evils of transition.” According to Keynes, Burke was at times guilty of pressing this doctrine “further than it will bear,” but there was “no small element of truth in it.” It was thus in the context of the Burke essay that Keynes first tried out his intuition about the futility of the long run that would become a famous quip some twenty years later.

Denaturalizing “The Long Run”

Let me at this point return to Keynes’s quip that “in the long run we are all dead” by placing it in its actual textual context. The line first appeared in A Tract on Monetary Reform, published in December 1923.

More specifically, it appeared in the third chapter on “The Theory of Money and of the Foreign Exchanges” and came in the context of a technical discussion of the quantity theory, which posited a direct relationship between the quantity of money and the price level. Keynes began with a definition of the quantity theory before introducing a hypothetical doubling of the amount of money (n).

The [Quantity] Theory has often been expounded on the further assumption that a mere change in the quantity of the currency cannot affect k, r, and k’—that is to say, in mathematical parlance, that n is an independent variable in relation to these quantities. It would follow from this that an arbitrary doubling of n, since this in itself is assumed not to affect k, r, and k’, must have the effect of raising p to double what it would have been otherwise. The Quantity Theory is often stated in this, or a similar, form. (CW 4, 65. Original emphasis. SE: In the passage n denotes the quantity of cash, k consumption units, r the amount of cash held by banks in proportion to their liabilities, and p the price level.)

At this point, Keynes’s voice suddenly soared from technical specifics to poetic indictment. “Now ‘in the long run’ this is probably true,” he commented on the claims of the quantity theorists.

But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us that when the storm is long past the ocean is flat again.” (CW 4, 65. Original emphasis.)

Note what has happened here. What had functioned in Burke as a critique of eighteenth-century French revolutionary millenarianism became in Keynes’s hands a critique of the equilibrium analysis offered by neoclassical economics. Indeed, Keynes explicitly extended this theoretical critique of equilibrium theories into a political critique of austerity measures derived from them.

As Keynes delighted in pointing out, in so far as orthodox economists (a group that had not long ago included Keynes himself) demanded interwar austerity based on the long-run extrapolations of neoclassical economics, they ironically mirrored the French Revolutionaries in demanding sacrifices in the present in the name of supposed benefits in the future. Economic austerity sacrificed the present on the altar of an uncertain future. Paradoxically, then, the economic policies of the Conservative Party were, according to Keynes, based on a Jacobin philosophy of history.

But there is more. Note, too, that Keynes refers in the passage to a specific long run: “this long run.” In the following sentence, “in the long run” is tellingly placed in italics to indicate that Keynes is not using it in his own voice. The target here is thus not any or all long-run thinking but one particular attitude toward the future. Crucially, for Keynes the future is not reducible to “this long run.”

His critique was only directed against the specific long run of neoclassical economics which abstracted away from both the present and the yet unwritten future. Such reductionism, Keynes observed, resulted from the seductions of naturalization since it was only in the neoclassical long run that the economy was assumed to have finally reached its “natural” state of equilibrium.

Keynes’s critique of this perspective was threefold.

First, and most basically, “the long run” of neoclassical economics lacked temporal specification. No one could know whether it would arrive in twelve months or seven years. Indeed, the concept seemed intentionally empty and designed to evade such questions.

Second, the neoclassical long run reflected a misuse of abstraction driven by the suspicious quest for a natural state of long-run equilibrium. Keynes returned to this critique repeatedly, not least in his preference for Malthus’s economic theorizing from “the real world” over Ricardo’s more abstract starting points (“Thomas Robert Malthus,” CW 10, 88). Since the future of mankind was shaped by the most irregular movements, to draw too straight a line from the present to the future was a sure way to mislead oneself.

Third, this meant that the abstract “long run” of neoclassical economics essentially evacuated politics from the future. Even if an equilibrium were to exist (a possibility Keynes came to doubt) and even if it were eventually reached, “this long run” fatally neglected all attendant political questions—not least those that concerned the costs of transition, the associated distributive burdens, and their effect on political legitimacy.

What was the point of training one’s eyes onto the comforting sight of equilibrium in the distance if the ship of society would be torn apart long before it could reach these shores? The neoclassical economists’ mantra of long run equilibria thus reflected a certain passivity that stepped back from politics and submitted to the forces of nature. From Keynes’s perspective this was as misleading analytically as it was callous politically.

Instead, Keynes turned his gaze away from the naturalizing quest for long-run equilibria and toward a genuine appreciation of a not yet determined future. This politicisation of future possibilities intentionally destabilized any extrapolated collective singular of “the long run” or “the future.”

Moreover, precisely because these unknown futures were not natural outcomes but only brought into being through open-ended debates and contestations it was crucial to attend to questions of political legitimacy in the present. But far from reflecting a myopic obsession with the present, this was testimony to a deeper appreciation of the political enmeshment of past, present, and future.

Future Possibilities

Keynes’s critique of neoclassical “long run” had several immediate implications. To begin with, it demanded far greater attention to how actions in the present are connected to not-yet-existing future possibilities. Rejecting the naturalized long run thus implied for Keynes at the same time a need to articulate broader future possibilities.

John Maynard Keynes, “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” The Nation and Athenaeum (October 1930), CW 9, 321-32. Source: ProQuest; New Statesman.

This is evident not least in Keynes’s own interest in alternative imagined futures, most famously in his essay on “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” (1930)

In the essay, Keynes famously turned toward a very long run—around one hundred years out—that allowed him to speculate how altered economic possibilities translated into new moral and political challenges of how to enjoy increased leisure time and develop new answer to the art of living.

Sometimes Keynes’s glance into a future of abundance is read as little more than an exercise in confidence building during the Great Depression. But for the most part, economists have seen in Keynes’s essay primarily a gloriously failed prediction that rising productivity would gradually translate into increased leisure time (see, for example, Lorenzo Pecchi and Gustavo Piga’s Revisiting Keynes: Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren).

For Mann, by contrast, Keynes’s vision of abundance looks less like an earnest but failed prediction and more suspiciously like a form of “bourgeois utopianism” (373). Not only does Mann thus detect in Keynesianism a conception of progress as the continuous development of the present, but there is also the lingering worry that the distant utopia is in fact meant to perpetuate the present unchanged into the future by pacifying present class relations. The underlying Keynesian instinct amounts from this perspective to an attempt “to cancel out the future by prolonging the present,” as Antonio Negri had put it.

But this critique, as Negri and Mann themselves partially acknowledge, is more effectively leveled against Keynesianism than against Keynes himself. Postwar Keynesianism’s commitment to perpetual growth coupled with a deep intellectual investment in modernization theory can indeed be read as offering a linear conception of growth as progress that served to stabilize a deficient present.

Keynes’s essay is neither an exercise in prediction nor a linear extrapolation. Instead, it is an explicitly speculative endeavour meant to stretch our imagination. After all, Keynes did not so much extend capitalism into the future as rather envisage a future in which the love of money—that “semi-criminal, semi-pathological … somewhat disgusting morbidity” (“Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” CW 9, 329)—could finally be overcome. To be sure, capitalism had a crucial role to play in this vision but its ultimate purpose was to assist in its own demise.

Crucially, Keynes envisaged post-scarcity not simply as a state of material abundance but as a social, moral, and political achievement based on shedding the love of money and re-learning the art of life. This was then no mere act of extrapolation to vindicate the present but a vision of political malleability meant to expand the imagination.

Experimentation and Pragmatism

The mode of social change that Keynes embraced in response to this challenge was a notion of open experimentation. If future possibilities were never simply outgrowths of a linear conception of progress that passively unfolded, they had to be created and cultivated through open-ended institutional experiments. Keynes thus complemented Burke’s insistence on political expediency with an embrace of experimentalism instead of tradition.

This openness toward new and untested ideas, which at first sight would stand in tension with his Burkeanism outlined above, was catalysed by the historical conjuncture of World War I and its aftermath, which, as we saw, fuelled Keynes’s conviction that neither the principles of nineteenth-century classical liberalism nor those of Marxism could any longer serve as an adequate “working political theory” (“National Self-Sufficiency,” CW 21, 235). Escaping the resulting impasse now demanded an embrace of experimentation precisely in the spirit of expediency.

Crucially, this was not technocratic experimentation about the best tools to achieve given ends. Nor was it scientific experimentation in search of objective knowledge to be universally implemented. Keynes’s understanding of experimentation and rationality was always closer to Bloomsbury and Freud than the natural sciences. His account of experimentation was consequently not simply geared toward the discovery of truth but it valued experimentation as an inherently valuable pluralistic activity. What was required were new ways of “experimenting in, the arts of life as well as the activities of purpose.” (“Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” CW 9, 332)

Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf playing dress up in Bloomsbury with Jack Hills and Walter Headlam, Source: The Charleston Trust.

Facing up to uncertainty without giving up on betterment required modes of open experimentation that operated both on an individual and an institutional level. For Keynes, this entailed nothing less than cultivating new forms of collective life and social cooperation below the level of the state. “The true socialism of the future,” he declared in 1924, “will emerge, I think, from an endless variety of experiments directed towards discovering the respective appropriate spheres of the individual and of the social, and the terms of fruitful alliance between these sister instincts.” (CW 19, 222) As Keynes argued in “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” the pessimism of conservatives and reactionaries had to be rejected precisely because their conception of the fragility of economic and social life left little room of genuine institutional experimentation.

Even while he left most institutional aspects of this notion of experimentation underexplored, Keynes did reflect on some of the requirements that could render such experimentation feasible and safe. His first plank was to point to the way in which open experimentation necessarily required the possibility of “free and remorseless criticism.” (“National Self-Sufficiency,” CW 21, 193)

Alongside such an openness toward critique, Keynes moreover envisaged that much of the experimentation he had in mind would occur in “semi-autonomous bodies” within and below the state (“The End of Laissez Faire,” CW 9, 288). These would be “semi-public,” not dedicated to commerce or profit but instead to how to share public spaces and cultivate public goods.

Here as elsewhere, Keynes consciously placed himself outside of interwar debates over planning by offering alternative conceptions of decentralized or independent bodies of administration that would be essential for crafting new tools of indirect economic steering—including what we have come to call macroeconomic policy. This left Keynes’s experimentalism in an ambivalent relation to democratic politics but, as he insisted in a 1939 interview with Kingsley Martin on “Democracy and Efficiency” (CW 21, 497), experimentation was not only compatible with democracy, the very nature of the experiment of democracy itself required a spirit of ongoing institutional experimentation.

Keynes’s Regime of Temporality

What could progress mean once cut off from linear teleologies? For Keynes, this was a challenge that applied to liberals at least as much as it did to Marxists. During the 1920s he consequently explored what it might mean to renew liberalism and socialism away from providential schemes of progress.

For Keynes, the rupture of the Great War had revealed that “[p]rogress is a soiled creed, black with coal dust and gunpowder,” as he put it in January 1923 in a piece in the Manchester Guardian (CW 17, 448). This did not mean that the concept of progress could be simply discarded but nor could it any longer be accepted in a straightforward manner. “We believe and disbelieve, and mingle faith with doubt.” (CW 17, 448) Progress had become perilous and contradictory terrain that stood in urgent need of revision.

In a March 1926 article on Trotsky in The Nation and Atheneaum, in which Keynes argued that historical analysis revealed the use of force alone to be remarkably impotent, he ultimately ended with a plea for a new marker that could provide temporal orientation. “We lack more than usual a coherent scheme of progress, a tangible ideal.” (“Trotsky on England,” CW 10, 67) This required not only a new political program but also a rethinking of temporality that moved away from all too linear, uniform, and quasi-providential conceptions of progress to instead grapple with the inherent uncertainty of proliferating futures without giving up on the possibility of betterment.

Keynes’s distinct conception of temporality, with its simultaneous rejection of intertemporal trade-offs and a commitment to experimentation both complements and challenges existing theorizations of the relation between past, present, and future. In his influential accounts of historicity, Reinhart Koselleck cast the emergence of modern historical time in the spatial metaphor of a widening gap between the space of past experience and a growing horizon of future expectations.

But where Koselleck sought to capture dominant societal modes of relating past, present, and future to one another, Keynes’s conception of temporality cannot be neatly folded into any of the widely accepted “regimes of historicity” (François Hartog) of either the nineteenth or twentieth century. It aligns neither with the providential logic of the progressive tradition, nor with the perpetual growth temporality of postwar Keynesianism, nor with the presentist tradition that Hartog sketches as dominating toward the end of the twentieth century.

Keynes’s stance instead explores the productive tension between the space of expedience and multiple horizons of experimentation, to adapt Koselleck’s spatialized language. What grounds Keynes’s conception of the present is thus not a stable notion of tradition or experience, but instead a concern with expediency that grapples with the political pressures of legitimacy. What opens up his horizon is not a linear expectation of progress, but instead a notion of open experimentation that embraces uncertainty.

In illustrating that there is no such thing as “the future” but instead only ever a proliferation of multiple yet unformed possibilities, Keynes flagged the centrality of the politics of such future time. Keynes’s denaturalization of “the future,” such as that offered by neoclassical economists but also frequently investors themselves, does double work here. On a first level, it functions of course as a critique of those specific conceptions of the future. But in rejecting the idea of the long run as mere extrapolation Keynes also offered an altered conception of temporality that helps to make visible a politics of competing conceptions of the future.

Keynes built on his appreciation of uncertainty thus an awareness of the power of divergent conceptions of future possibilities. Speculative visions of the future are thus performative in the sense that they feed back into how people act in the present. As Keynes argued in the seminal twelfth chapter of the General Theory (1936), our estimates of even the comparably near future are so inescapably obscured by uncertainty that they cannot form any reliable, let alone calculable basis for our actions in the present. And yet we have to act.

The conclusion Keynes derived from this account was not to dismiss expectations about the future but on the contrary to insist that these conflicting guesses about future states of the world are both inescapable and powerfully performative, not least in making some futures more likely than others. As he summarized in the preface to The General Theory (1936), “changing views about the future are capable of influencing the quantity of employment.” (xvi) Expectations thus have a profoundly reflexive, performative dimension that easily render them self-fulfilling or self-defeating, often tragically so.

Keynes consequently turned his critical attention to the kinds of conventions we often fall back on to bridge the inevitable gap between uncertainty and urgency—not least the presumption that the future will resemble the past. But rather than vindicating these conventions, Keynes instead pointed to the need for pragmatist experimentation and an experimental attitude that could cultivate alternative future possibilities in the present.

Conclusion

Keynes’s conception of temporality has been widely misunderstood by conventional readings of his quip about the long run. Keynes did not disparage grappling with future possibilities. Instead, his target were empty invocations of “the long run” that merely extrapolated the present. Such an empty collective singular of “the future” was not only a profoundly misleading guide to current affairs, it also perversely undercut actual future possibilities.

The very performativity of competing conceptions of future possibilities demanded bold action in the present. Far from turning his gaze myopically to the present, Keynes offers an account of temporality that sought to highlight the entwinement of present and future.

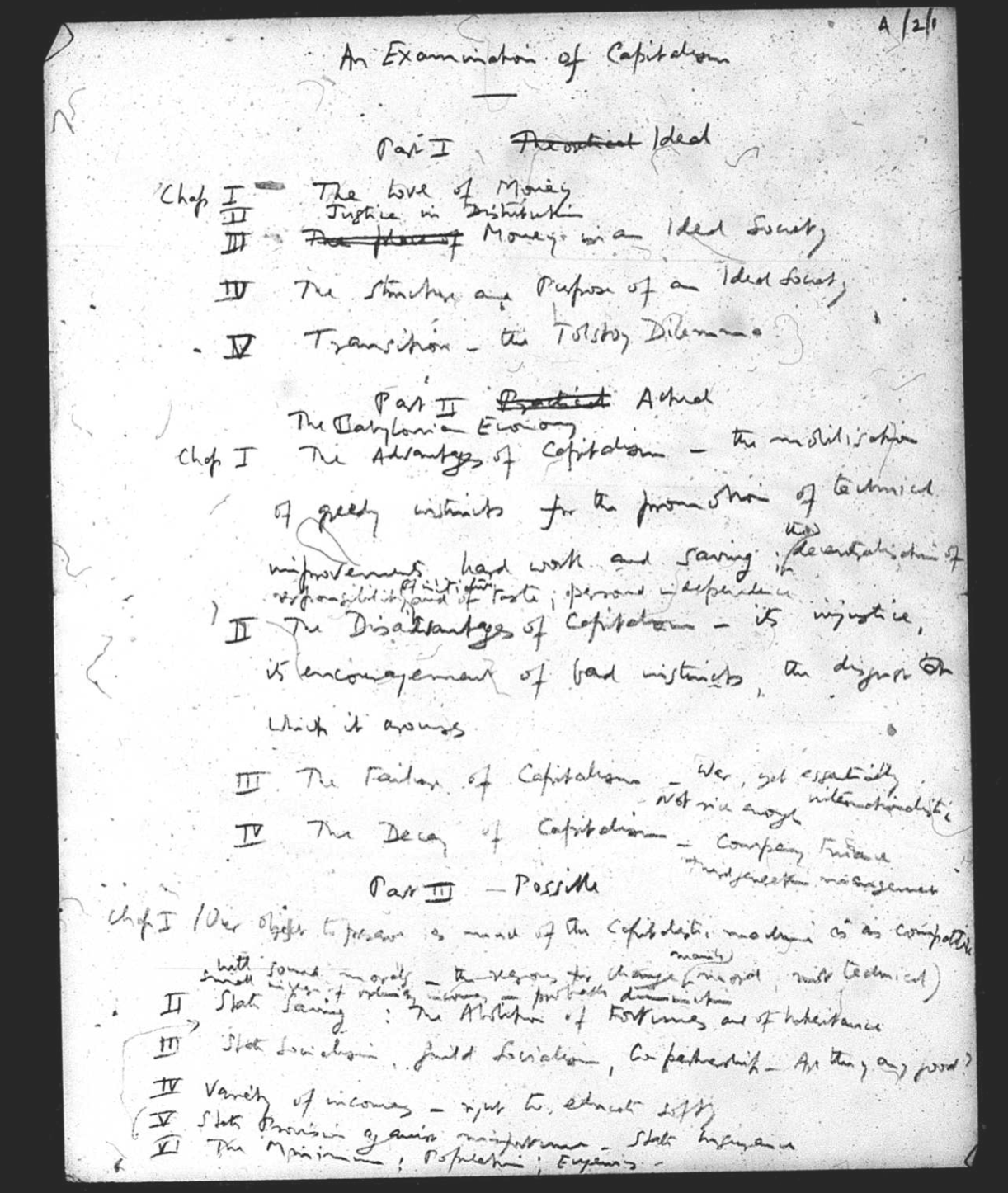

John Maynard Keynes, “Draft sketch of ‘An Examination of Capitalism’” (c.1926), Keynes Papers, King’s College, Cambridge, JMK/A/2/1.

Recovering Keynes’s attention to the temporal dimension of political action is a promising starting point for deciphering his complex and seemingly contradictory relation to capitalism, suspended between the three temporalized registers of the “ideal”, the “actual” and the “possible”.

But Keynes’s insistence on the politics of multiple possible futures also confounds dominant ways of theorizing and calculating intertemporal choice under conditions of radical uncertainty. Keynes reminds us in this context that attempts to domesticate “the future” not only underestimate the depth of our ignorance but that they also themselves performatively shape the range of possible futures.

For Keynes, accepting radical uncertainty did therefore not translate into either myopia, nihilism, or despair. On the contrary, his appreciation of the performative politics of competing conceptions of the future precisely culminated in a call for bold and creative action. Doubt, as Albert Hirschman pointed out in a parallel argument, does not have to be immobilizing but can in fact motivate action.

Keynes’s stance thus highlights the need to grapple with the temporal element of political action under uncertainty, not least by more explicitly articulating the complex entwinement of present actions and multiple future horizons. One of the tools for holding short run and long run together without flattening the future was his insistence on experimentation instead of calculation.

For Keynes, such an experimental attitude to intertemporal choice was meant to open up alternative futures that are not yet known or even imaginable; and thereby fill the future with possibilities that are not outgrowths of the present but first have to be experimentally discovered and cultivated. (This pragmatist response to uncertainty aligns Keynes in this regard with recent work by Charles Sabel and his co-authors on “experimental governance” and “democratic experimentalism”.)

Rather than reflecting a myopic presentism, this also means that Keynes’s account of the politics of time may have more to say to us in our current moment of climate crisis. To be sure, Keynes’s own experimentalism was premised on the modernist idea of an open horizon of endless possibilities. Today, it is far from clear that we still have time to experiment.

And yet Keynes’s attention to the performativity of political temporalities under conditions of radical uncertainty illustrates the profound need to fashion new conceptions of temporal politics that can experimentally open up the remaining future possibilities of our deficient present.