Chartbook 342 A history of America's medico-industrial complex ... seen from the step-down ward.

One of the things that kept me sane during my recent stay in hospital was dipping into Gabriel Winant’s, The Next Shift. It is an extraordinary account of the way in which working-class family lives, heavy industrial labour and hospital and care work were intertwined in America’s quintessential steel town, Pittsburgh and the state of Pennsylvania.

Source: Harvard UP

Not for nothing it is the winner of

2022, Frederick Jackson Turner Award

2022, C.L.R. James Award

2022, Isaac and Tamara Deutscher Memorial Prize

For me, five big stories stand out from Winant’s remarkable synthetic history.

Winant shows us how in the mid-20th century health care and industry in the United States were coupled together. This was institutionalized in the decentralization of hospital care in smaller local facilities. In the era of high industrialism, local hospitals served the needs of a working-class whose bodies were being consumed by the industrial process. This local connection was further underpinned through local structures of funding.

Secondly, Winant then adds the crucial link to the household division of labour, showing how the hospital supplementing domestic care work and offering employment to working-class women. The hospital and the factory were thus tied together not just through industrial labour, but through the working-class family unit.

Winant then describes how that equilibrium of the 1950s and 1960s was destroyed by deindustrialization. But, rather than the welfare system simply collapsing, the “iron rice bowl” model of local hospitals closely tied to industrial communities, was replaced in the 1980s by expanding flows of publicly funded health care.

In this expanding space of health care, which absorbed an ever larger share of US GDP, Darwinian competition between health care providers, saw expanding, University-linked “research” hospitals exerting an ever more dominant position in regional and global health economies. In Pittsburgh, as in many other postindustrial cities across the USA, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center displaced US Steel as the largest employer.

Meanwhile, care work itself was subject to ever tighter corporate control and oversight with multiple new divisions within the hospital labour force and a deterioration of working conditions and pay. The increasing precarity of care work fed back into a crisis of working-class family life.

This is a simplified rendition of what is a complex and compellingly illustrated argument.

Winant’s is a proudly Leftist account. The “emplotment” is correspondingly downbeat, driven ultimately by the narrative of the declining fortunes of America’s industrial working-class. One might ask whether this can really do justice to the dynamism and performance of American health-care, which on many metrics has produced significant improvement in health outcomes through the large-scale application of sophisticated imaging and interventions.

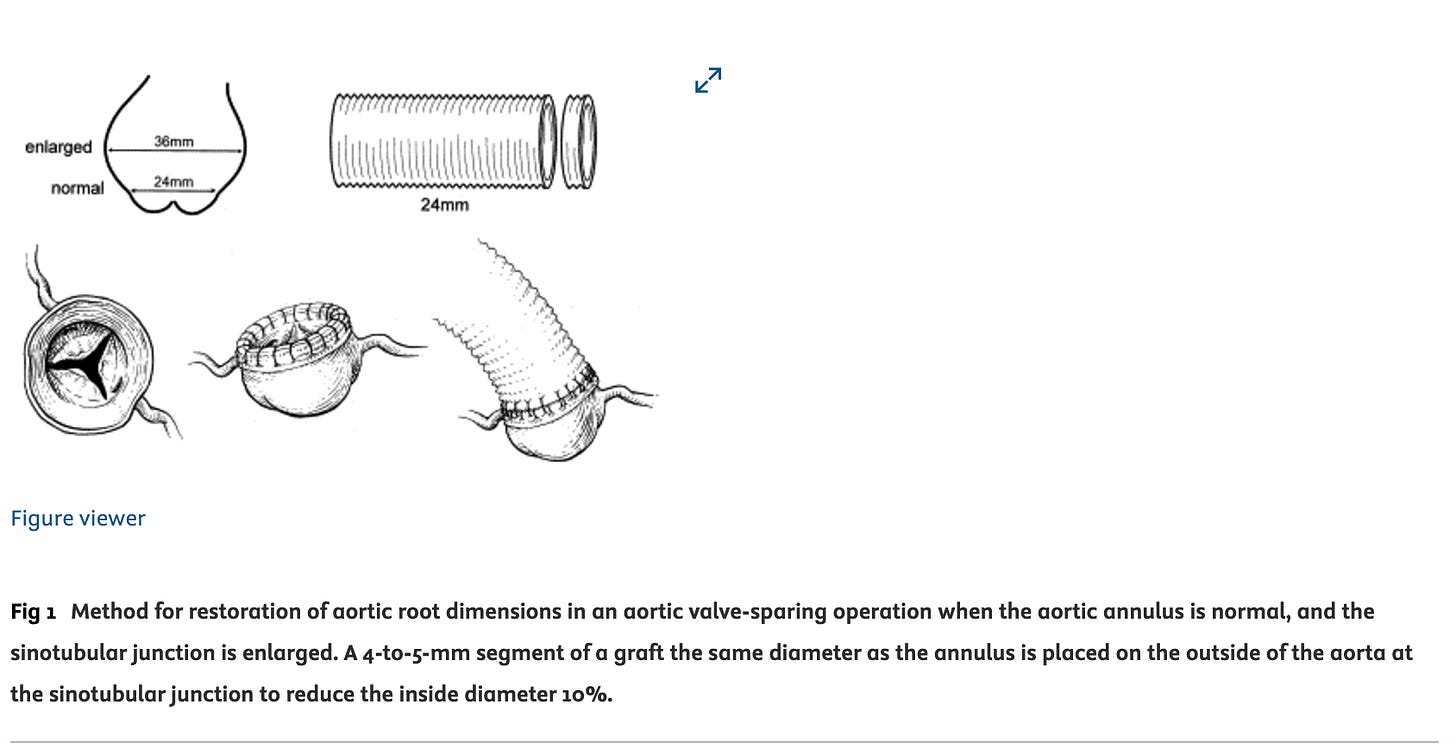

Much as one may bemoan the end of local hospitals, one might ask whether a counterfactual of continued localism is realistic. My own heart condition, for which I underwent surgery on December 10, has seen a huge improvement in treatment and survival chances since the 1990s. That is owed largely to high-tech medicine of the kind that only large hospitals can deliver. High tech monitoring and, for complex procedures, Smithian economies of learning by doing, are the key to safety and success.

And what are the consequences of centralization in giant hospitals? Some are clearly negative. Winant provides us with a vivid image of deskilled and exploitative labour conditions, especially in peripheralized regional hospital. The care I experienced in one of the winner hospitals of the new era, provided by well-unionized staff, was certainly subject to corporate control and driven by a relentless process of monitoring and data collection. But the element of human interaction and actual care was not fully displaced. It was clear that the entire system was actually only kept working by multi-faceted and highly skilled initiative on the part of the nurses, many of whom were nursing in the fullest sense of the word, engaged simultaneously in technical, medical and emotional labour, organized around an ethic of care. The deskilling and fragmentation of tasks was incomplete at best and that is what kept things going.

When - inspired by Winant - I enquired about family life, childcare etc, the nurses I talked to stressed how they appreciated the flexibility of their working rosters. These, no doubt, are amongst the relative winners of the modern US health care system.

Clearly, there are other histories that could be written of the development of modern hospital medicine in the United States. But first and foremost we should appreciate what Winant has done in his book. His integration of industrial and economic history, labour, social and family history in a single narrative is utterly eye-opening.

Furthermore, the way that Winant elaborates the theoretical undergirding of his narrative in pieces such as the Deutscher Prize Lecture published as “The Baby and the Bathwater: Class Analysis and Class Formation after Deindustrialisation” in Historical Materialism October 2024, further deepens one’s appreciation. His is a truly important voice not just in US social and labour history, but in social theory and in thinking about the contemporary world.

The abstract for the HM piece reads as follows:

This paper is an edited version of the Deutscher Memorial Lecture delivered in November 2023 which expands upon The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America. It develops an account of the productivity limits of interpersonal service work more firmly rooted in Marxism and argues that the separation of social reproduction from production is primarily economic rather than political. This theoretical device is then deployed to argue that there is indeed a global ‘crisis of care’. This crisis is triggered not only by destabilisation of earlier care regimes, but also the encounter between the productivity limit and new forms and expanding volume in demand for care. Finally, this crisis is linked to the new global sociology and politics of gender and sexuality. Methodologically, the paper argues for renewed attention to the empirical specificity of proletarianisation processes, rather than ‘class abstractionism’.

In my semi-dazed state in hospital, rather than the finer points of social theory, which Winant’s lecture explores brilliantly, what came to mind was another chain of association: Pennsylvania, steel-town hospitals, Braddock …

Braddock is the struggling postindustrial town from which maverick Pennsylvania Senator John Fetterman launched his career. It is also where the extraordinary photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier grew up and honed her skills and found her zone of engagement.

Her show at MOMA was, for me, one of the highlights of 2024.

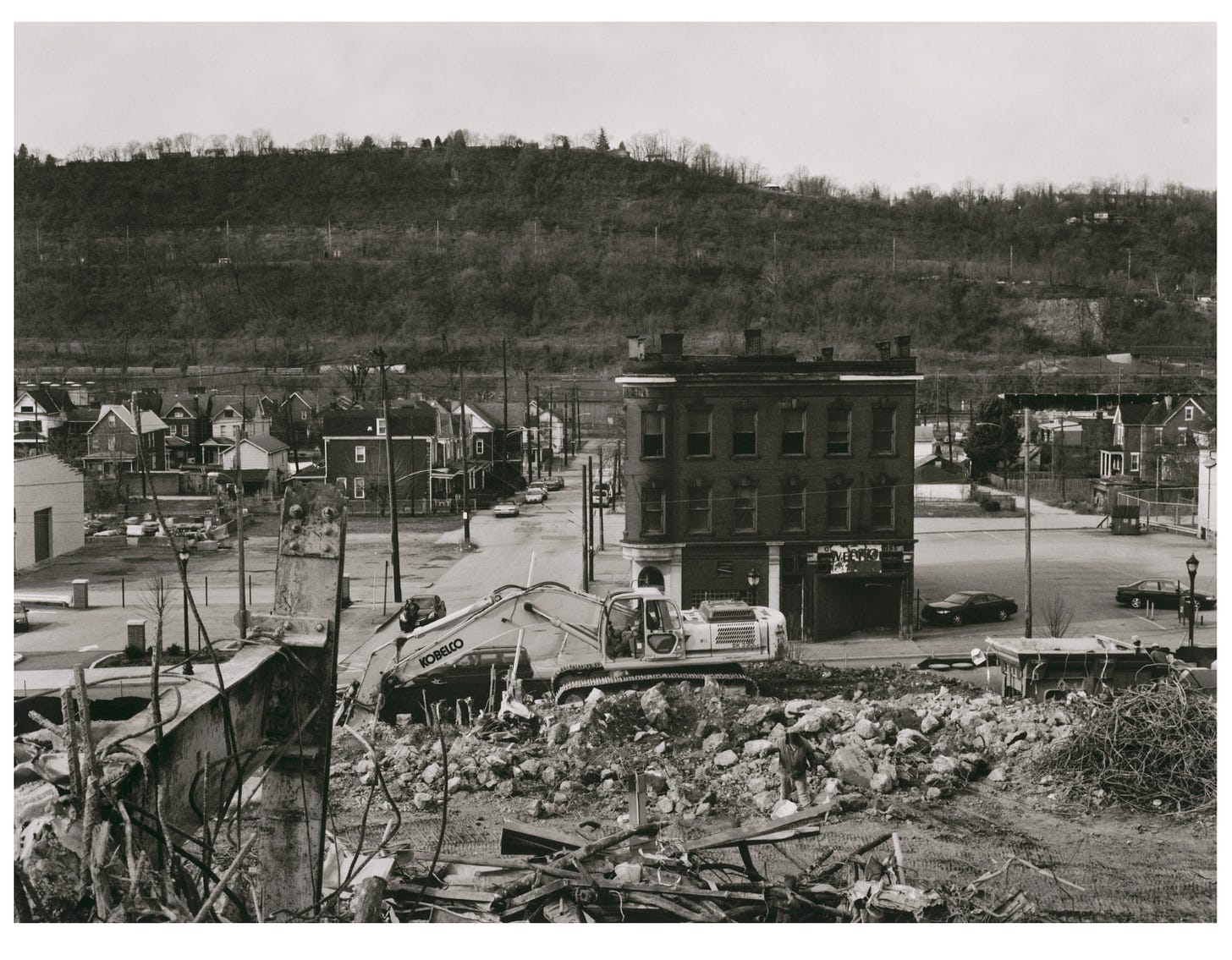

One of her most evocative series of photographs documents the struggle to maintain the Braddock hospital following its incorporation into the UPMC system. A story that also features in Winant’s account. It does not end well.

As the MOMA website comments:

In her acclaimed photographic series The Notion of Family (2001–14), Frazier has followed in the rich tradition of American social documentary photographers who have incorporated biographical details into their work, in effect making the personal political. She has often turned the camera on herself and her family, weaving her own personal narratives into the larger history of Braddock. Fifth Street Tavern and U.P.M.C Braddock Hospital on Braddock Avenue depicts the remnants of the town’s only hospital. Its controversial demolition left residents, including the artist and her family, without a local health clinic. In contrast to Frazier’s gripping portraits, this work presents a sweep of dilapidated town blocks almost entirely devoid of human presence. At the center of the composition, a barely visible solitary figure sits in a bulldozer amid the rubble. What was once a beacon for health and healing has been reduced to a no-man’s-land, imbued with an eerie stillness.

It is hard not to see Frazier and Winant as engaged in a common project which is documenting and analyzing the modern American working-class experience. Images by Frazier adorn Winant’s book. As Frazier writes in the catalogue of the show:

From the Steel Valley, along the Monongahela, Allegheny and Ohio rivers to the Flint River in ‘Vehicle City’, Flint, Michigan; from historical mineshafts in the Borinage, Belgium, to a historic labour union in Lordstown, Ohio; and from community health workers in Baltimore, Maryland, to a labour leader and civil rights activist in California’s Central Valley, I’ve used my camera as a compass to direct a pathway toward the illuminated truth of the indomitable spirit of working-class families and communities in the twenty-first century. For this reason, it is incumbent upon me to resist—one photograph at a time, one photo-essay at a time, one body of work at a time, one book at a time, one workers’ monument at a time—historical erasure and historical amnesia.

Frazier’s work is so impressive in part because of the way in which she handles intimacy and the human body. In a fascinating way, this never involves a retreat from the “public”, or her more general “social” themes. Rather it is in the bodies that she photographs that we see those forces at work.

As Rebecca Losin writes in New Left Review:

“In ‘Landscape of the Body (Epilepsy Test)’ (2011), a two-panel image, we see the back of the artist’s mother, Cynthia, exposed by an open hospital gown, a cluster of wires connecting her to a medical device. The opposing image of the ruins of Braddock hospital duplicates the wires in its exposed cables, sketching an affinity between the human body and built environment.”

Source: Whitney

I remember pausing in front of this image on a visit to the MOMA show in the summer. Now, as I look down on the 30 cm incision in my chest, where the surgeons opened me and then neatly closed me up, and imagine blood pulsing through a length of one-inch polyester tube sewed onto my heart, I can’t take my mind off it.

Ahead of the operation, Cam Abadi and I spoke about the astonishing history of open-heart surgery, its economics and geography.

Three weeks into recovery I still feel my brain struggling to catch up with and make sense of this life-saving and yet traumatic intervention.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

So very relieved to hear of your positive heart surgery outcome, Mr. Tooze, and appreciate you sharing both your personal experience and your reading suggestions. Wishing for you a rapid return to your old self and continued good health and perkiness to you and your Beloveds in the coming year!

Thank you for another great article. Gabriel Winant's article in Historical Materialism is open access for those wishing to read further (issue 32 number 2).

Wishing you all the best.