What are the stakes in the struggle over Trump’s trade strategy? In answer to this question there was a brilliant piece on Bloomberg this weekend by Shawn Donnan and Anna Wong that merits extended discussion.

Their starting point is that in charting the path ahead we have to understand the history of tariffs under the first Trump administration, what his team may have learned and what their priorities are going to be in the years ahead. But the questions goes far beyond this.

To try and narrow the range of uncertainty the Bloomberg team argue that we need to distinguish:

the drama of Trump’s free-wheeling public statements — like his currency-rattling tariff threats to Mexico, Canada and China last week and a fresh warning to the BRICS economies on Saturday — from the slower-moving processes by which tariffs are designed and enacted. The drama has started immediately. Tariffs may build more gradually.

Though Trump is threatening all sorts of action immediately on taking office, the most likely scenario is that his team tempers this into a sequenced series of tariff hikes designed to “maximize negotiating leverage and tariff revenue while shielding US consumers” from a price shock.

Bloomberg has access to a lot of important people on the inside of decision-making and on that basis it suggest a scenario something like this.

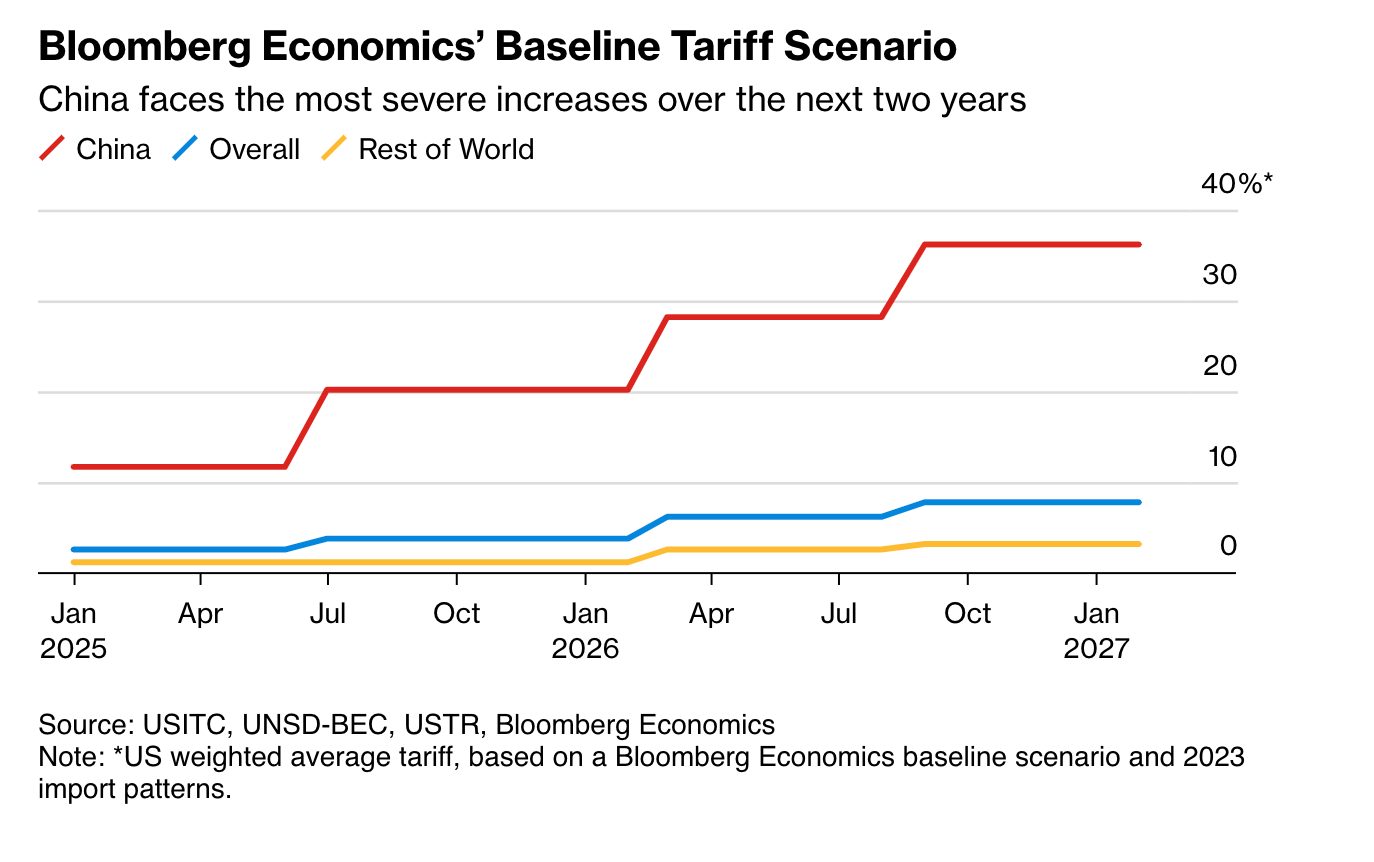

The combined impact would be a tripling of average US tariffs to almost 8% by the end of 2026. If that’s how things play out, US imports and exports of goods will drop from 21% of the global total today to 18%, including a plunge in US-China trade. US growth gets dinged, inflation faces fierce cross currents from higher tariffs and a stronger dollar, bullish stock markets have a bearish hurdle to clear and unemployment rises. But the extreme effects of the sky-high universal tariffs Trump floated on the campaign trail are avoided.

For all its animosity, Trump’s most recent rant about punitive sanctions on Mexico, Canada and China over migration and fentanyl don’t deviate from this overall scenario.

What is harder to gauge is the impact on specific sectors. As another Bloomberg report remarks:

Tariffs of that magnitude on the roughly $97 billion worth of auto parts and 4 million finished vehicles that come to the US from Canada and Mexico would be “devastating,” Wolfe Research analysts said in a note on Tuesday. Average new-car prices would rise about $3,000, they said, adding to an almost $50,000 cost that many consumers are struggling to afford.

Whether Trump will want to risk this is anyone’s guess. Last time he was dissuaded by some well-timed lobbying from blowing NAFTA up.

Trump’s choice of hedge-funder Scott Bessent as Treasury secretary was reassuring to markets worried about disruptive action on trade. Bessent has said his priority is to raise growth to 3 percent. But it is also clear that this time around key appointees were vetted on their attitude towards trade. Tellingly, Robert Lighthizer, Trump’s trade warrior of the first term has been slighted because the Trump team don’t think he is a man for bold moves. As Donnan and Wong point out:

Trump last week picked Jamieson Greer, a longtime aide to Lighthizer and his former chief of staff, to serve as US Trade Representative. That suggests Lighthizer, who at age 77 remains the sharpest protectionist mind in US policymaking, may have to settle for having his protégé in the administration rather than his own station.

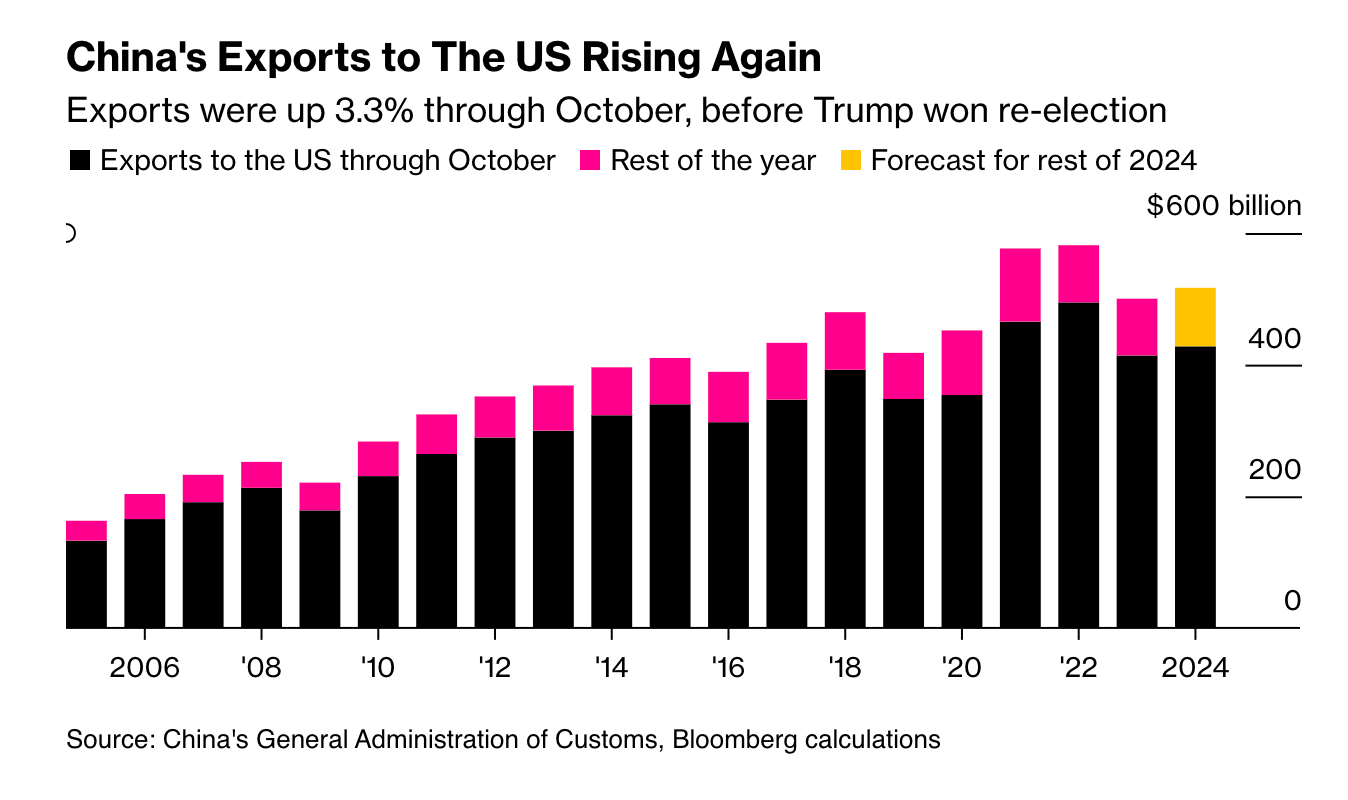

Greer has talked tough about decoupling from China and the headline figures will certainly add fuel to the fire. US imports from China are now substantially higher than they were than when Trump left office at the end of 2020.

To complicate the picture Trump compensated Howard Lutnick, a high-profile player in his transition team, with the job as Commerce Secretary with special responsibility to “lead our Tariff and Trade agenda”. Though boisterous, Lutnick has no experience in trade policy and in that same role Wilbur Ross faded out of sight in Trump’s first administration.

Assuming that Trump’s policy is not driven by impulse alone, Bloomberg suggests that a plausible first step would be to start “ratcheting up of tariffs in mid-2025” using

“existing lists from the Section 301 investigation his administration launched in August 2017 and that the Biden administration used to retain tariffs on Chinese imports. Initially, Bloomberg Economics’ expectation is that this path will lead to 15% additional tariffs on a broad range of consumer products ranging from pinball machines to pajamas and ballpoint pens that were limited targets during Trump’s first term. That would mean Trump’s first action would be to return tariffs to the levels proposed during his first administration before January 2020, when he signed what was called the “Phase One” deal with Beijing. It’s a plausible step given China has not lived up to the first deal and that it has an enforcement mechanism that can be easily triggered.”

The open question is whether that would be just the opening move in a continuous escalation aiming at deeper decoupling - as has been the case with tech sanctions - or whether Trump uses that opening salvo as a way to restart the trade talks that led to his Phase I deal in 2019-2020. Assuming no deal is reached, it seems likely that the Trump administration will progressively ratchet up the tariffs on China to an eye-watering 75 percent. If this comes to pass, Bloomberg thinks it will result in a loss of over 80 percent of Chinese direct exports to the USA.

At the same time Trump has also boasted of his plans to introduce a general tariff on all imports. Assuming the administration does not act on impulse this might consist of a “3% additional tariff, first on intermediate goods and later on capital goods imported from the rest of the world.” Overall this would result in US tariffs rising from 2.6 to 7.8 percent, the most dramatic increase since Smoot-Hawley in 1930.

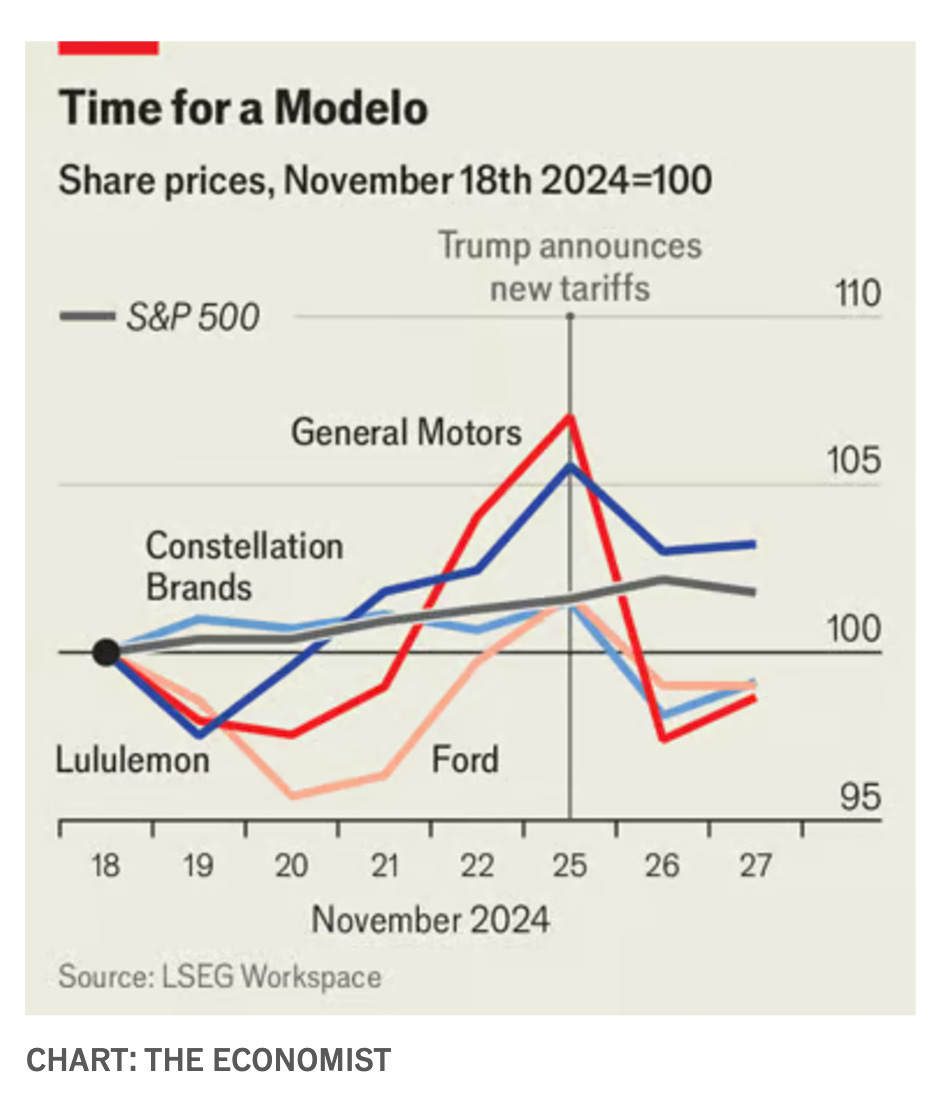

The impact is likely to be highly uneven. As the Economist reminds us:

Particular industries and regions would suffer more pain. Despite its own oil-and-gas boom, America still imports 4m barrels of crude a day from Canada, for instance—much of which goes to the Midwest. More than half of America’s imports of fruits and vegetables come from Mexico. Carmakers, which have built factories in Mexico to produce vehicles for the American market, are especially vulnerable. America’s Ford and General Motors are among those that would be affected, as are Japan’s Nissan and Toyota, and Germany’s BMW and Volkswagen. The stock prices of several of the more exposed importers slumped on September 26th. General Motors’s fell by 9%; Ford’s by almost 3%. Big importers of materials from affected countries, including Lululemon, which sells clothes, and Constellation Brands, which imports Mexican beers such as Corona, Modelo and Pacífico, fell by 2-4%.

The hope that the Trump administration will not merely act on impulse is more than wishful thinking because of what we know about tariffs in the first term. As Bloomberg reports:

Under what former staff still call the “Hassett algorithm” — named after former Council of Economic Advisers Chair Kevin Hassett, who oversaw the compilation of the initial tariff lists against China — those levies targeted mainly parts and machinery to minimize the impact on inflation and GDP. They also focused on goods for which American buyers could find substitutes. For his second term, Trump picked Hassett to serve as director of the White House’s economic policy shop, the National Economic Council, where he could be as influential as Bessent on the details of tariff design.

A strategy aiming to minimize the impact on US consumers might well follow the Hassett algo. But, this time there is also another consideration. Trump has taken to touting tariffs as a revenue-raising device.

Extending the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which slashed income and corporate taxes, would cost $500 billion per annum from 2026. If Trump follows the phased path for tariffs suggested by the Bloomberg scenario, this should bring in $250 billion in tariff revenues. When discussing the issue on the campaign trail Bessent cited potential additional revenue from tariffs in this ballpark - $2.5 trillion to $3 trillion in revenues over 10 years. But as a true Trumper he added a further twist: “tariffs would generate a broader revenue boost by bringing more production to the US. That sort of reshoring, he said, would “substantially increase” domestic tax revenues even if the corporate rate is lowered to 15%, as Trump has proposed.” Let’s call this the Trumpian equivalent of the Laffer curve, which famously promised that cutting taxes would increase revenue. This time around the idea is that one lot of taxes - tariffs - will increase production and revenue so much that other taxes can be more easily cut.

Interestingly, if tariffs begin to feature in Trump’s budget planning this adds another twist - Congress.

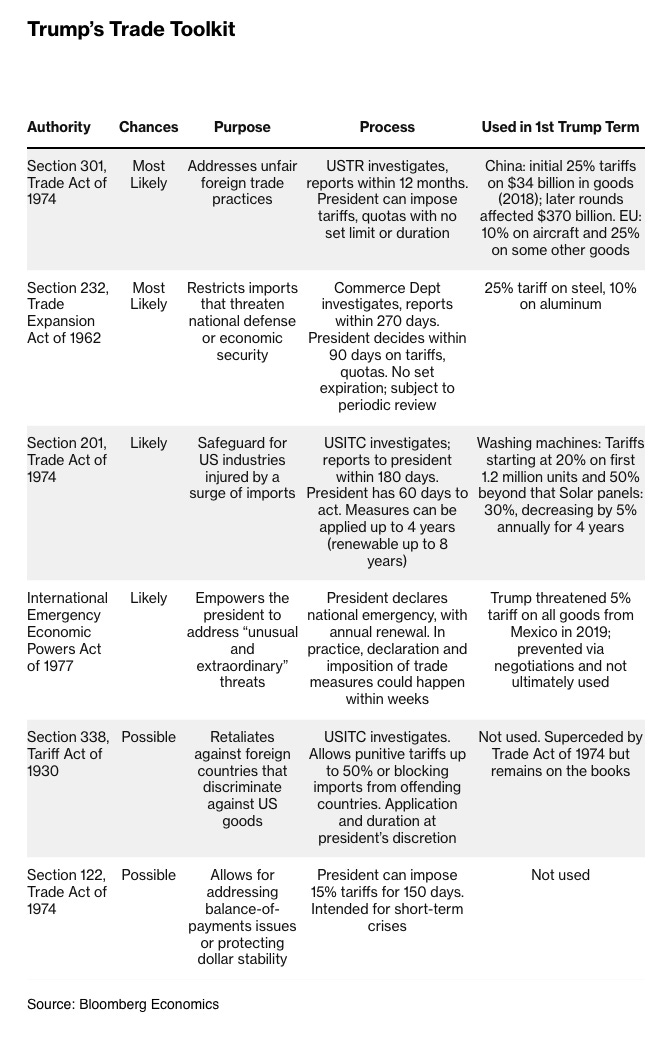

Much of Trump’s trade policy can be enacted by the Presidential pen using powers accreted to the White House over the years. Bloomberg offers this useful list:

Section 301 was used against China in the first Trump administration but would be hard to use against Mexico and Canada. Section 232 is handy but applies only to specific goods. In the view of the Economist, the most straightforward means by which Trump could enact his program

“would be the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). This allows the president to impose tariffs with few limits (“to deal with any unusual and extraordinary threat…if the president declares a national emergency with respect to such threat”). IEEPA has attractive features for Mr Trump. “It’s an emergency power, so there’s minimal procedural requirements. So, he could do it very quickly—on day one, if he wants,” says Warren Maruyama, a former general counsel for the United States Trade Representative. Mr Trump was the first to invoke the law to impose tariffs when, in 2019, he threatened a 5% levy on all Mexican goods in retaliation for illegal migration. And there is another important precedent. In 1971, when Richard Nixon took America off the gold standard and in effect ended the first Bretton Woods system, he imposed an extra 10% duty on all imports by declaring the need “to strengthen the international economic position of the United States” to be an emergency. Courts upheld Nixon’s actions.”

But, if prospective tariff revenues start entering into budgetary wrangling with Congress, the road could get rougher.

As Donnan and Wong remind us: “Including higher tariffs in a new tax package would mark the first time since Smoot-Hawley that Congress has voted to increase import levies. … Trump can only afford to lose three Republican senators if he wants to get his tax cuts through. But GOP members from farm states and free traders may well object to his using tariffs as an offset, according to Kyle Pomerleau, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. All it would take is a handful of them worried about retaliation against US agricultural exports to stall or derail the process.”

If Trump goes even further to revoke the general normalization of trade relations granted following China’s WTO accession, he is likely to face a broad based rallying of free trade forces, notably including the US chamber of commerce.

But in the end the key regulating factor is public opinion. As the Economist puts it:

The likeliest constraint on Mr Trump will … be fear of backlash from the markets and the public. “More than half of our fresh fruits and vegetables are from Canada and Mexico…Super Bowl season is right around the corner. Do we really think Trump’s going to impose a 25% guacamole tax on his first day in office?” says Scott Lincicome of the Cato Institute, a libertarian think-tank. … The court of public opinion is probably the only one that can curb Mr Trump’s instincts.

Meanwhile, the decisive macroeconomic question is how trade policy is integrated with broader policy towards the dollar.

Michael Pettis is one of the most cogent defenders of the need for the US to address its chronic trade deficits that are financed by large capital inflows. This is not a developmental path chosen by the US alone. It is one that results from the meshing of US domestic political economy with that of its trade partners. To break out of this impasse Pettis argues for radical measures to redress the balance between capital inflows and the trade deficit. In a recent twitter thread he argued this means taking an open-minded approach to tariffs. Railing at the dogmatism of most economists on the subject, Pettis insists that one does far better talking to economic historians.

But, precisely if you take the Pettis view of protectionism as a blunt but nevertheless defensible tool in a situation of global imbalance, Trump’s latest threats to impose sanctions on BRICS countries for seeking to break their reliance on the dollar, make no sense.

So, amidst the infighting in the Trump circle and technical, political and geopolitical arguments over tariff design, these are the broader issues of political economy that are at stake.

(1) Will Trump’s administration continue to answer to the interests of Wall Street and the foreign policy blob with their vested interests in global dollar hegemony? Or is the new administration more willing than all its predecessors to allow the dollar’s position to slide, making room for a consistent strategy that favors domestic production.

(2) In that strategy of domestic production, is the administration willing to do what is necessary to ensure that the benefits are not concentrated merely amongst the most affluent. Relying on trickle down will not support a broad-based expansion in domestic-produced consumption.

A consistent “national Keynesian” approach to US economic policy would need to meet both these criteria. If it showed any signs of doing so, it would, following Pettis’s logic be a defensible economic policy position. But thinking historically (MP ;)) it seems unlikely that a business-dominated cabinet of right-wingers headed by Donald Trump will deliver on either of them.

So what scenario seems more likely to develop? What seems far more likely is a dysfunctional protectionism, that hurts consumers and has little positive impact on domestic production or on the US macroeconomic balance that will continue to be dominated by large fiscal deficits and a giant issuance of government debt that will be swallowed up by global investors whose excess of dollar earnings is generated by the success of their exports worldwide. In other words, what seems most likely is not a consistent turn to national production, but a nastier and even more unequal continuation of the status quo, with a hollowed out Federal government, increased uncertainty and severely negative repercussions for America’s relations with important international partners.

To oppose that deterioration into a third- or fourth-best scenario, the defense of the current second-best by tactical appeals to economic expertise and simplified liberal versions of economic history seems defensible as a a way of responding to the urgency of the moment. Certainly one should expect no less from professional economists. As Pettis acknowledges, this is a moment of historical significance. Get it right, and real things may change for the better. Get it wrong and what is at stake is more than doctrinal point scoring. To argue for open-mindedness on protectionism when power lies in the hand of Donald Trump and his cronies is truly to take a historical gamble - a gamble at long odds - and with that comes also a measure of responsibility for what ensues. Talk to a historian and that is what they should tell you.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

"To argue for open-mindedness on protectionism when power lies in the hand of Donald Trump and his cronies is truly to take a historical gamble - a gamble at long odds - and with that comes also a measure of responsibility for what ensues."

But this misses critically the point MP tries to make, that businesses, workers, and middle class savers have increasingly ceased to see this as a gamble at all, because right now the economy for many is terrible. Despite the constant crowing by folks like Krugman that people just don't understand how good they have it rn, a metric shitton of people do not feel they have it good and they can directly trace this to policies which the Democrats cling to, like free trade and certain regulations that work out to NIMBYism. If you can't afford a house, you're real income is demonstrably worse than your parents, and the only jobs around you are service jobs demeaningly catering solely to the whims of a class of people living large, then yeah you don't see this as a risk because actually quite credibly the free trade argument is a bad one.

The Democrats in failing to even engage with trade discussion are just ceding the whole field to Trump, and this dismissiveness besides being another case of quite openly self-interest elitism in most cases is also missing the very real probably that protectionism could be steered in a beneficial direction. Beneficial not just in a narrowly nationalist sense even, but globally, because ultimately it is the race to the bottom that complete free trade enables and the removal of any teeth to labor or environmental standards that has prevented Western nations from progressing for the last several decades. So long as businesses in dictatorships are favored by our trade policy, we basically ensure that our own businesses either become like them or die off. If instead we held countries we trade freely with to the same standards, the people in those countries would benefit in the long run too.

Could you pursue the following issue: The United States shops primarily at national outlets: Amazon, Costco, Trader Joe's, Lowe's, etc. and these maintain the same or similar pricing throughout the country. On the other hand, average wealth varies so greatly from state to state (and county to county within states.) When pricing is the same it's cheap for us in the wealthy states and expensive for say Mississippi. On the other hand, where prices are adjusted, such as gasoline and some food stores, aren't the wealthy secretly subsidizing the poor? Two Americas, therefore a rotten political situation based on hatred.