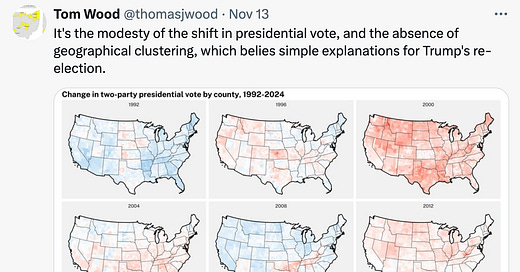

Trump’s victory was no landslide. The vote share did not really shift by much.

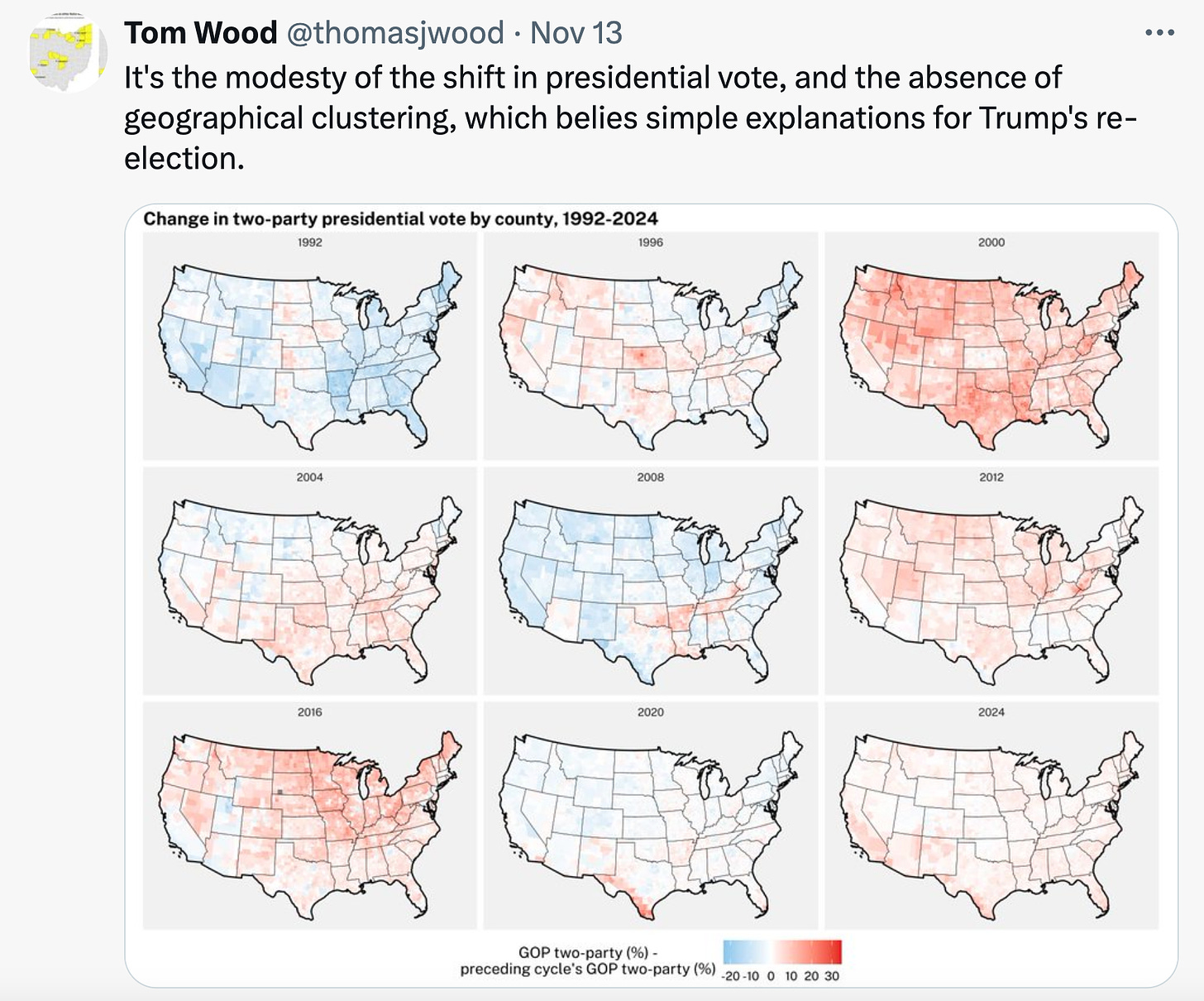

By the standards of elections in developed countries in 2024, Harris’s defeat was a mild rebuke for an incumbent - amongst the least severe seen anywhere on the planet.

The essential fact about US politics in the current moment remains that the two party system anchored in the ancient constitution divides the country almost half and half. Those cleavages run through society including through the working-class and the business interest. Tim Barker is absolutely right when he says in New Left Review’s Sidecar:

Perhaps the safest thing to say is that the working class, as a class, didn’t do anything. The vote is evidence of dealignment, not realignment: voters below $100,000 split basically down the middle.

However, this does not mean that the election outcome was not shaped by powerful sociological forces. And these forces mark out some pretty clear lines in America’s fragmented and incoherent class system. If the class analytic of workers v. owners is not helpful in making sense of Trump’s victory, the idea of a revolt against the Professional Managerial Class (PMC) may be more so.

The PMC was a term coined in 1977 by Barbara and John Ehrenreich. The term designated the rising mass of college-educated white collar professional and managerial workers whose ambiguous role in modern Western politics the Ehrenreich’s were trying to explain.

Being neither manual workers, nor owners of the means of production, these groups do not occupy clear-cut positions within a Marxist class schema. As a result, skeptics continue to question the “C” in PMC. Can one really say that the PMC acts as a class? This is all the more piquant because, whether they agree or not, the vast majority of the people debating the PMC - including the author and readers of Chartbook - fall broadly within this category, assuming it has any value.

Nothing in what follows depends on assuming the reality of the PMC as a class, in the sense of an organized working-class or capitalist class. I am going to use the term here in a looser sense. It suffices to acknowledge that there is a divide in American society between the college-educated and those without college-education and a divide between those people who broadly align around the “liberal” values taught in such institutions and those that don’t. Nor does this divide need to line up cleanly with other markers. “Class politics” in the sense I am using it here is a more open-ended, dynamic and underdetermined practice.

What matters is some version of the following narrative:

In the 1960s and 1970s many professional and managerial people contributed to social movements that were clearly progressive. Furthermore, for the vast majority of folks who count themselves as progressive this alignment has a deep logic all the way down to the present day.

As Gabe Winant, one of the sharpest observers of the contemporary scene, noted back in 2019 in N+1:

For all the cynicism and compromises that professional pretensions engender, professional labor (i.e. the labor of the PMC, AT) does carry a utopian seed—in the impulse to create and disseminate knowledge, to care for the sick, or to defend the rights and dignity of the democratic subject.

And yet what is also undeniable is that in the late 1970s and 1980s large and powerful parts of the PMC broke with any association with classic, working-class. left-wing politics, rooted in the trade union movement. Instead, they provided their support to the agenda of neoliberalism. Despite its endless critiques of the state and its rhetoric about markets, actually existing neoliberalism was the latest iteration of PMC politics. Neoliberalism was a managerialism.

The effect was a twofold entanglement.

A large part of service and professional work became marketized and corporatized. This polarized the PMC category itself into winners (e.g. highly paid legal professionals) and losers (e.g. adjunct teacher in universities or public school teachers in Red states). Some speculate that the PMC is losing all coherence and will eventually realize its common interest with the working class, a hope that has persisted for half a century.

At the same time, despite this polarization, mainstream public and corporate life, from the elementary school and creche to the commanding heights of large-scale corporate capitalism took on many of the values championed by the most vocal members of the PMC, including, for instance, Sheryl Sandberg-style corporate feminism and class-blind Diversity Equity and Inclusion initiatives.

The outcome in electoral terms in the US from the 1990s onwards was an increasing alignment of the Democrats with College-educated voters, an alignment that was particularly strong for women and minorities. Figures like the Clintons and the Obamas personify this coalition.

By 2008 this corporate-PMC synthesis made a large and tempting target for populisms of the left and the right. These populisms pitted “the people” against an elite bloc that was more often than not personified, not by oligarchs or the owners of the means of production, but by members of the PMC. Perversely, the much remarked upon resentment of working-class voters, particularly men, triggered by new patterns of inequality and disadvantage, vented itself in the first instance on elementary school teachers and social workers, often women, who found themselves grouped with “beltway liberals” in the crosshairs of right-wing populist vitriol.

In the US the bugbear of the right was the Democratic establishment at all levels. In Europe the EU and its bureaucratic institutions have made a tempting target for right-wing populism. It is not by accident that international and transnational agencies like the UN, EU and NATO come under populist anti-PMC attack. Domestic PMC-led technocracy has its global analogues. And as the Biden administration has demonstrated the commitments on the part of liberal establishment to those institutions are selective but durable.

Trump and Brexit in 2016 were early breakthroughs for the new anti-PMC politics.

The Trump shock of 2016 caused soul-searching in the Democratic party elite. The principal wager of the Biden administration was an effort to react to the first wave of anti-PMC revolt by widening the Democratic electoral coalition so as to attract trade unionists and working-class Americans back into the fold. In many ways this was ironic. The fact that the American working-class is increasingly feminized and diverse is no conceit of woke PMC ideology. Under Biden the party chased the image of the blue-collar production worker, almost as hard as they would eventually chase the respectable centrist Republican.

In 2020 when COVID demonstrated the harsh and dysfunctional reality of governance under Trump, the Democrats won back a majority. Though not for the anti-vaxxers, but for a majority of the population, COVID was a “PMC moment”. Nurses, doctors and lab scientists mattered, along with logistics experts and people who could get things moving again. It was not merely coincidental that COVID handed a PMC-dominated Democratic party a surprise victory. It was not for nothing that it was the Democratic majority in Congress that carried the US under Republican Presidents, both through the crisis of 2008 and that of 2020.

In 2024 with the electorate wanting a faster return to normality - resentments concentrated in the superheated discussion of “inflation” - what came back to the fore was the anti-PMC coalition that Trump rallies like no politician before him. As Barker rightly stresses, this cuts across the lines between workers and capital. But once we put the specter of the PMC in play, a pattern of alignments does become clear.

Harris, a Californian, tech-set, black, woman lawyer is the very embodiment of the PMC. Is it surprising that she proved to be unprecedentedly unpopular with Latino men? According to Axios:

Hispanic people represent 46% of New Mexico's oil and gas workforce at a time when progressives are pushing a transition to renewables. … Close to one-third of workers in construction are Latino, and only 20% of Latino men ages 25-29 have college degrees. Republicans are gaining ground by default. But Trump tariffs and mass deportations could hurt U.S.-born Latinos and create a backlash.

Similarly, white women without College education favored Trump over Harris by huge margins, as they had done over Clinton and Biden. Though the motives were no doubt complex, this was in large part surely a knowing vote against the prevailing PMC construction of feminine and feminist identity that ruled out the possibility of any woman voting for a man like Trump.

Going back to the 18th and 19th century in which the PMC first took shape, one of their defining features was their espousal of enlightened forms of religiosity. Over time that has blended into out-right secularism. In American Universities today there are few minorities rarer than a true-believing evangelical. When PMC commentators scratch their heads and wonder how anyone who took their religion seriously could vote for Trump, they underestimate the prolonged struggle in which religious Americans quite reasonable believe themselves to be engaged and their own role in that struggle. This pits faith, not against run of the mill sinners like Trump, but against the far more formidable juggernaut of liberal modernity. According to the Salt Lake Tribune:

Exit poll data from CNN and other news outlets reported that 72% of white Protestants and 61% of white Catholics said they voted for Trump. Among white voters, 81% of those identified as born again or evangelical supported Trump, up from 76% in 2020 and similar to the 80% of support he received in 2016.

For elements of the business class, what the PMC stands for is the regulatory state and its dangerous inclinations. That can mean too much regulation or a tendency to insist on reforms that might challenge deeply embedded and highly profitable sectional interests.

Within the business class, we can safely assume that the American gentry - the owners of car dealership, construction contractors etc i.e. the classic petit bourgeoisie - broke heavily in Trump’s favor. They resent the taxes, which they pay out of their large incomes. They despise regulations in general, but cling to those that help to solidify the protected status, for instance, of car dealership, or property rights.

Scrappy, mid-tech Silicon Valley billionaires crowd behind Trump, because the platform giants favor the corporate liberal synthesis offered by the Democrats.

In finance it is hedge funds and private equity that lean towards Trump, firms that pride themselves on their antediluvian, red in tooth and claw corporate style. By contrast, the urbane corporate leadership and professional staff of the big banks leans towards the Democrats. How, after all you can vote for or donate to a candidate whose felony conviction would disqualify him from any senior corporate management position?

Fossil fuel interests lean towards Trump because he celebrates oil and gas production. But this is more than simply a matter of profit calculation. It is a matter also of sociology and managerial culture. You can touch oil. You can smell gas. By contrast, there is no issue more quintessentially abstract, more quintessentially “PMC” than climate change and environmental policy in general.

To be clear these are not fixed or given alignments. The chains of association are to a degree arbitrary. There are working-class feminisms and anti-racisms. There are liberal hedge funds. What is at stake here is an anti-PMC politics which is not given and is not dependent simply on empirical facts, but is discursively fashioned and made. And for those purposes the figures of Clinton and Harris could hardly have been more ideal.

Thinking in terms of an alignment of anti-PMC forces is, of course, a simplification. But it offers us the chance to go beyond the realignment-dealignment dichotomy. It helps to explain Trump’s ability to mobilize both working-class votes and business support. It also helps to explain the self-righteous rigidity of the Democrats.

The besetting weakness of the PMC-Democrats is to imagine that there is nothing beyond their bubble, as defined, for sake of argument, by the weekend edition of the New York Times. Beyond lie only ignorance and sin.

The besetting error of the Trump camp, by contrast, is to imagine that the modern world can actually function without the expertise, discipline and labor provided by the PMC. Like the narrow mindedness of the liberal PMC elite, this is a failure of realism.

Care, research, education, stewardship, institutionalized respect are not just attractive values, in which, as Winant reminds us, no progressive politics can deny its investment. In complex modern societies they are functional necessities. The rhetoric of the likes of Trump and Musk towards PMC roles like the civil service, the contempt they show for institutions like the NIH or the Fed, is indicative of a disastrous failure to understand what holds modern society together. It would be comical were it not so dangerous. Astonishingly, anti-PMC skepticism on the right now extends even to the legitimacy of the higher ranks of the military command chain and the FBI.

It is indeed a “dark logic”, as Alex Bronzini-Vender calls it, that the Democrats have recently required a “world-historic catastrophe" to breathe life into” their “political fortunes”. But that fact has a grounding in the respective coalitions organized by the two parties. Crises are PMC moments. And we have so far been lucky. In both 2008 and 2020 the warhorses of the Democratic party - Pelosi, Schumer et al - provided the Congressional majorities necessary to allow failing Republican Presidencies to cope. We have not yet had to weather a crisis in which the Republicans had full control in Washington.

What has become obvious with the Clinton-Trump-Biden-Harris-Trump sequence is that the Democratic formula is itself increasingly a driver of crisis. It is not capable of providing reliable electoral wins. And when it does have power, nostalgia for the bygone era of hegemony and the reflexes of US globalism - a quintessential product of the 20th-century PMC - tend to accelerate crisis in the form of aggressive claims to US leadership and a resurgent neoconservative revisionism. It was not for nothing that the Biden administration aligned Trump, climate and China as the triple threat to their vision of America’s destiny.

In the first Trump administration, expressive gestures of rupture with the status quo were tempered by vested interests and the functional imperatives of the moment. The administration then inherited an economy with plenty of slack and a relatively calm geopolitical environment. Until 2020 few complex trade-offs were called for. When COVID hit, the Trump administration and the Republicans in Congress rapidly decomposed. How the Trump administration will actually look remains to be seen, but the environment today is far more complex and will test the anti-PMC politics of the Trump administration far more seriously.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

I still do not think Adam gets it. The attack against the professional class doesn't come from some abstract disgust of the professional class. It comes from the fact that the professional class has been so wrong on so many things and yet believe they know what is right and what is wrong because they are credentialed and so they should be the ones everyone should listen to.

Adam, I follow your work on LRB as well. All this talk about elites and classes bothers me. Big dark money and Republicans have been working for 60 years to reverse civil rights, social insurance and environment gains by outright lying to a gullible public. After hard work and much spending, they have cornered the legislative, judicial and executive branches of power. Educated, inner-directed people who are not swayed by lies or advertising naturally have shifted toward the Democratic Party because it actually has public policy goals. Right now we're one step from dictatorship. It's an existential crisis for the country, and liberals have tried to prevent it. Big money and small scruples won. Don't get fancy.