Chartbook 335 The shame of US maternal mortality - mounting crisis or chronic condition?

Social Reproduction Series #2

Look at global figures for maternal mortality, one of the most basic indicators of health care provision and societal well-being, and what stands out are, first and foremost, the huge numbers of maternal deaths in Africa. That was the theme of yesterday’s post (#1 in a new series on social reproduction which I find myself starting).

The second thing that is eye-catching is the deteriorating trend in maternal mortality in the USA. The US likes to boast of being the wealthiest country in the world. It spends more on health care than any other country. And yet according to CDC data, endorsed by the WHO and many other expert groups, America’s maternal mortality record is disastrous. Mothers die at much higher rates than in other advanced economies.

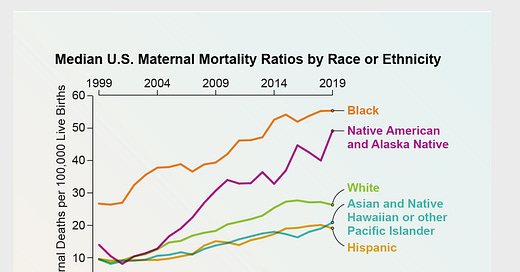

Source: Scientific American

Contrary to the trends in every other advanced economy, the data show a doubling of maternal mortality in the US. For native American and black women, the numbers are nothing short of drastic. The maternal mortality rate for black women in America is forty to fifty times greater than for women in Switzerland.

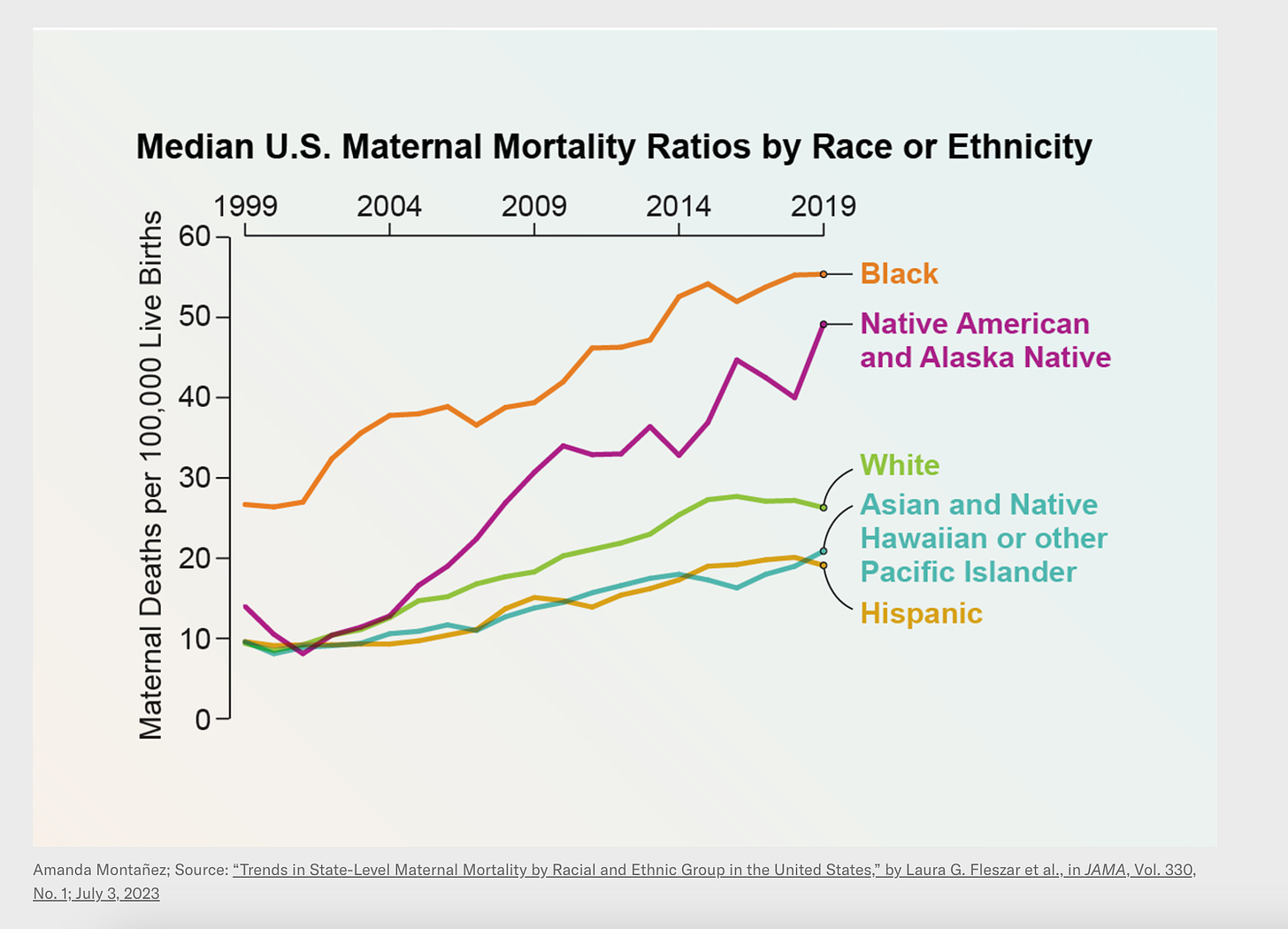

Source: Commonwealth Fund

That this isn’t a matter of national soul-searching and at the very top of the policy list, is staggering. That, instead, abortion and the defense of basic reproductive rights are the center of the controversial debate is a sign of perverse derangement.

Maternal mortality is one of those stark things about the United States, which most of us glimpse in a shocked way out of the corner of our eyes, rather than confronting it head on. Perversely, part of this tacit acceptance comes from the fact that the bad news about maternal mortality in the US is so obviously part of a piece with so many other terrible features of life in America.

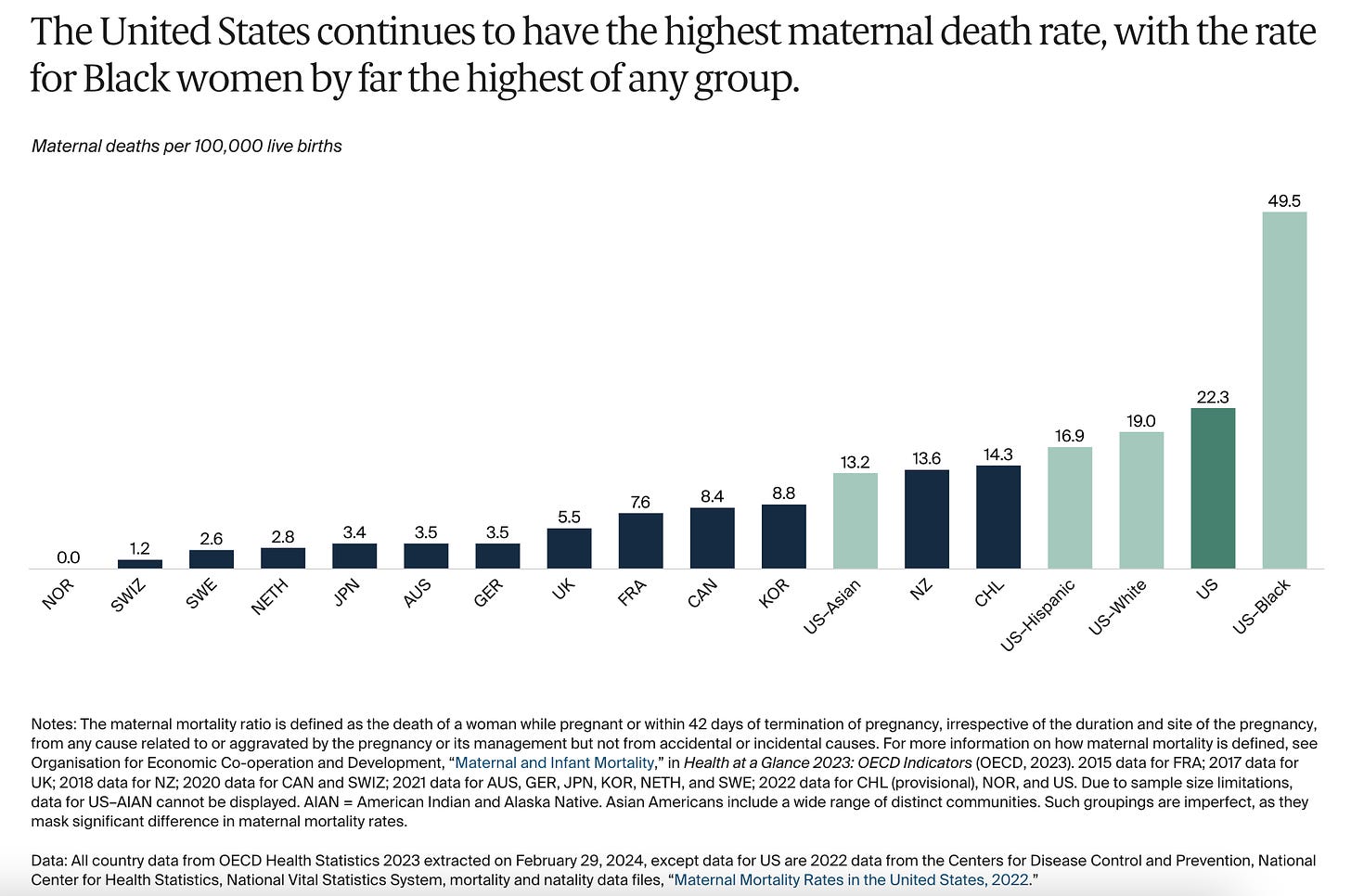

We know that overall life expectancy is shorter in the US and that infant mortality is higher, as well. So it is no surprise that maternal mortality is bad too.

Source: Commonwealth Fund

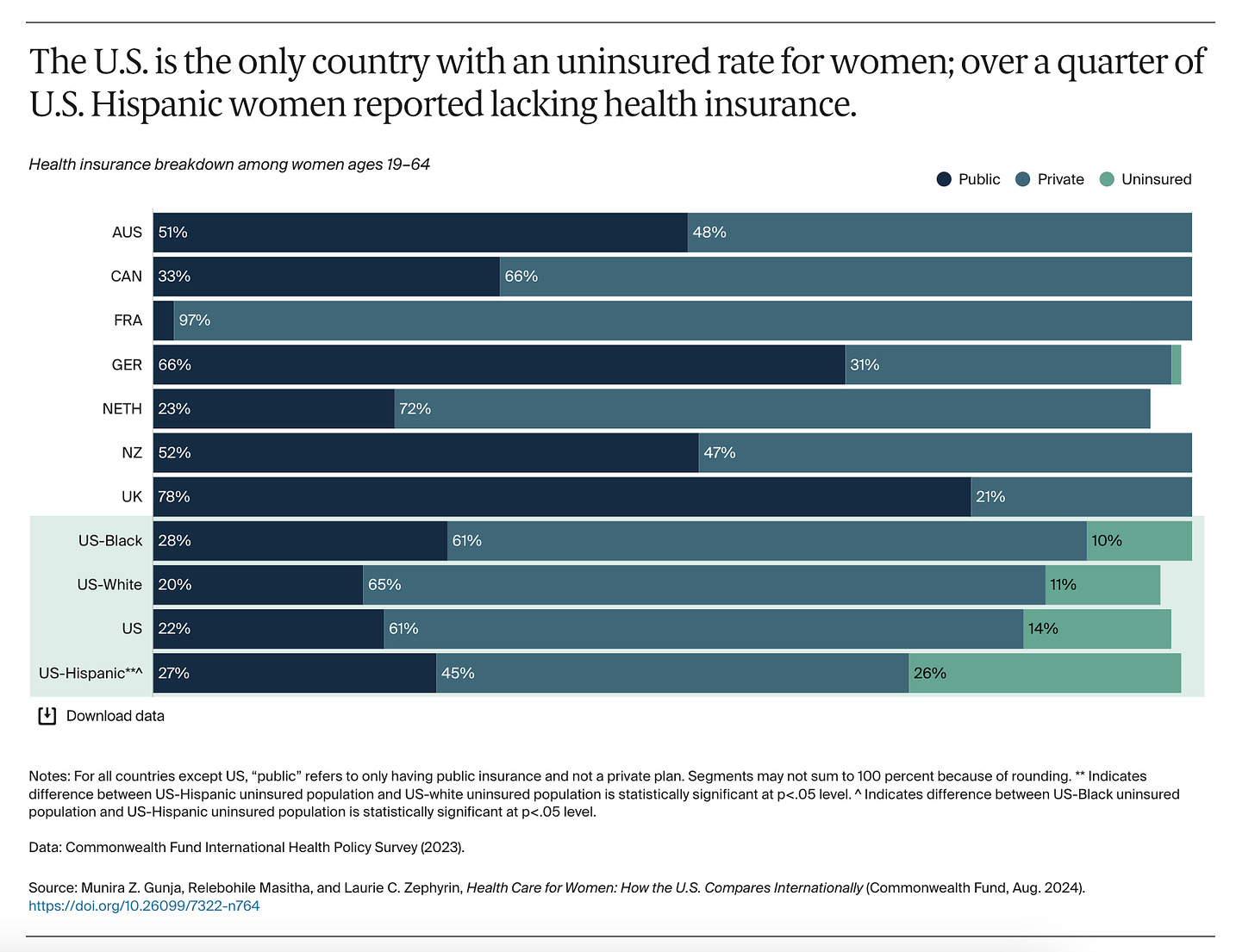

It is clearly related to pervasive, multi-dimensional inequality, poverty, inadequate access to health care, inadequate maternal rights in the workplace.

Source: Commonwealth Fund

Women and particularly pregnant women at the intersection of these lines are clearly at high risk.

Source: Commonwealth Fund

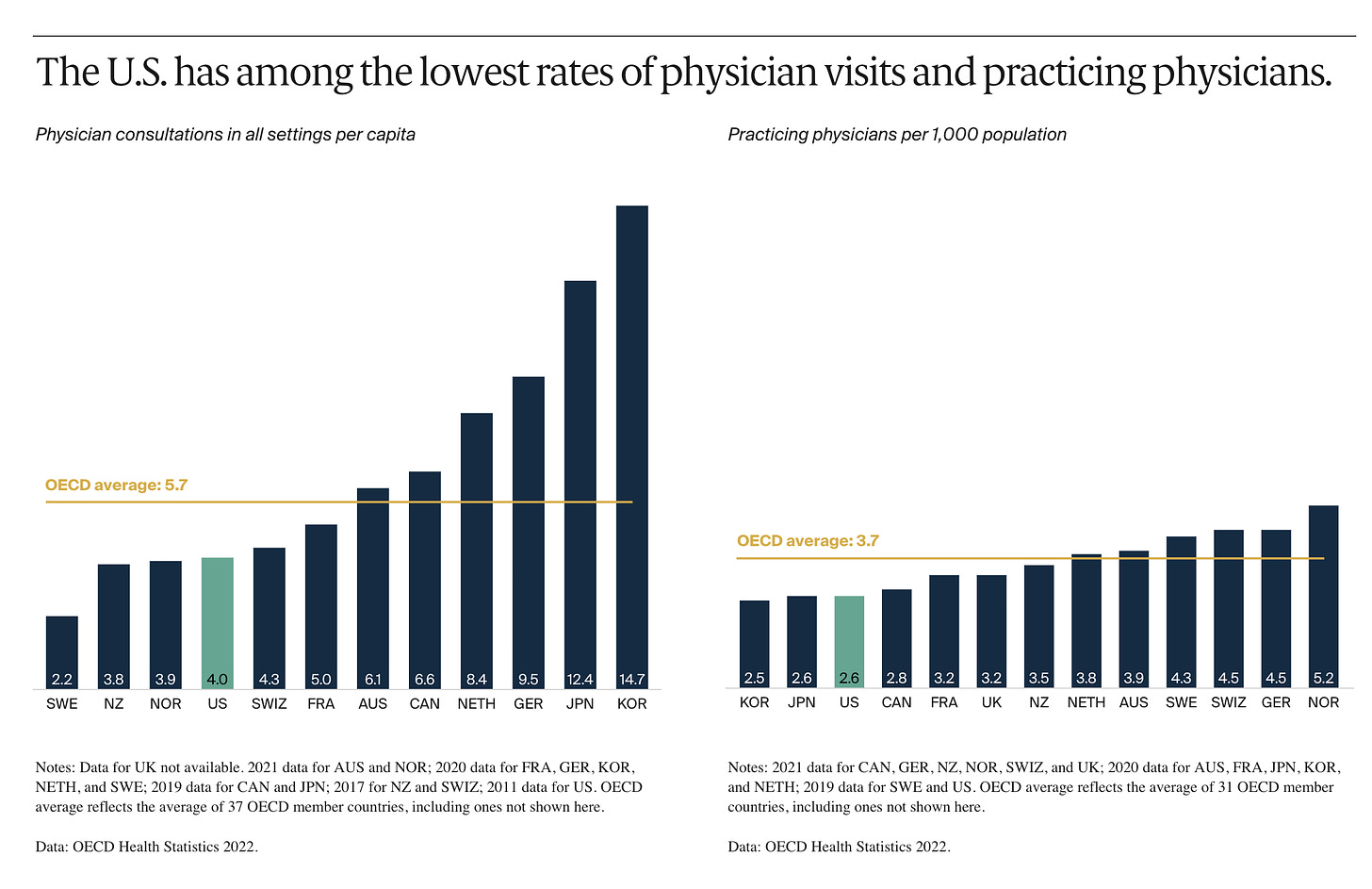

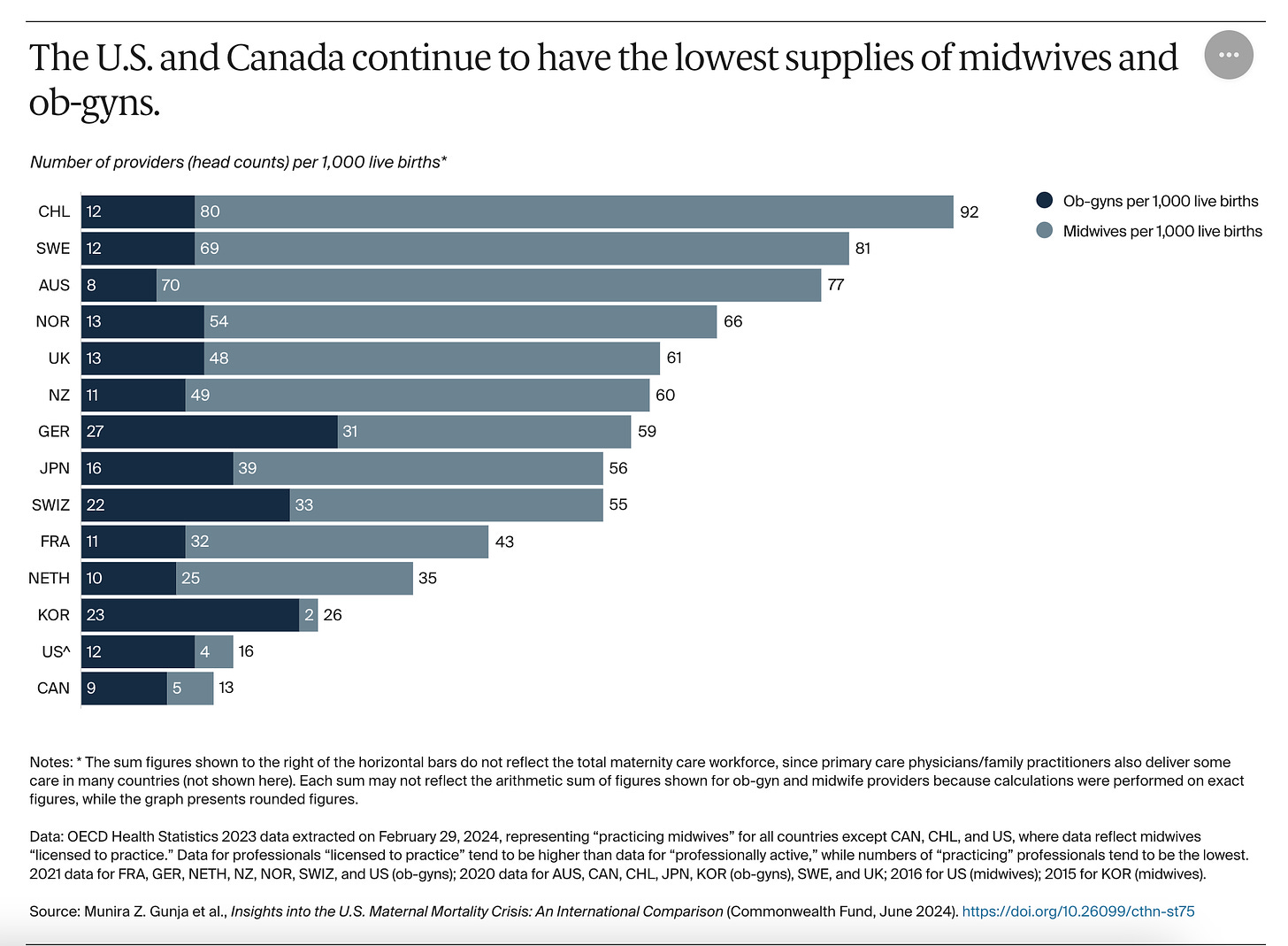

For all its exorbitant health spending, the US has the lowest availability of relevant medical personnel.

Source: Commonwealth Fund

The bad trend in the data goes hand in hand with other narratives of deterioration such as “deaths of despair” and rising obesity.

On the other hand it also goes hand in hand with the risks of an aging society and one that likes medical interventions that come with risks. In this case an important factor associated with an increased risk of complications is the rising rates of cesarean sections in the 2000s, a trend which has plateaued in the last ten years.

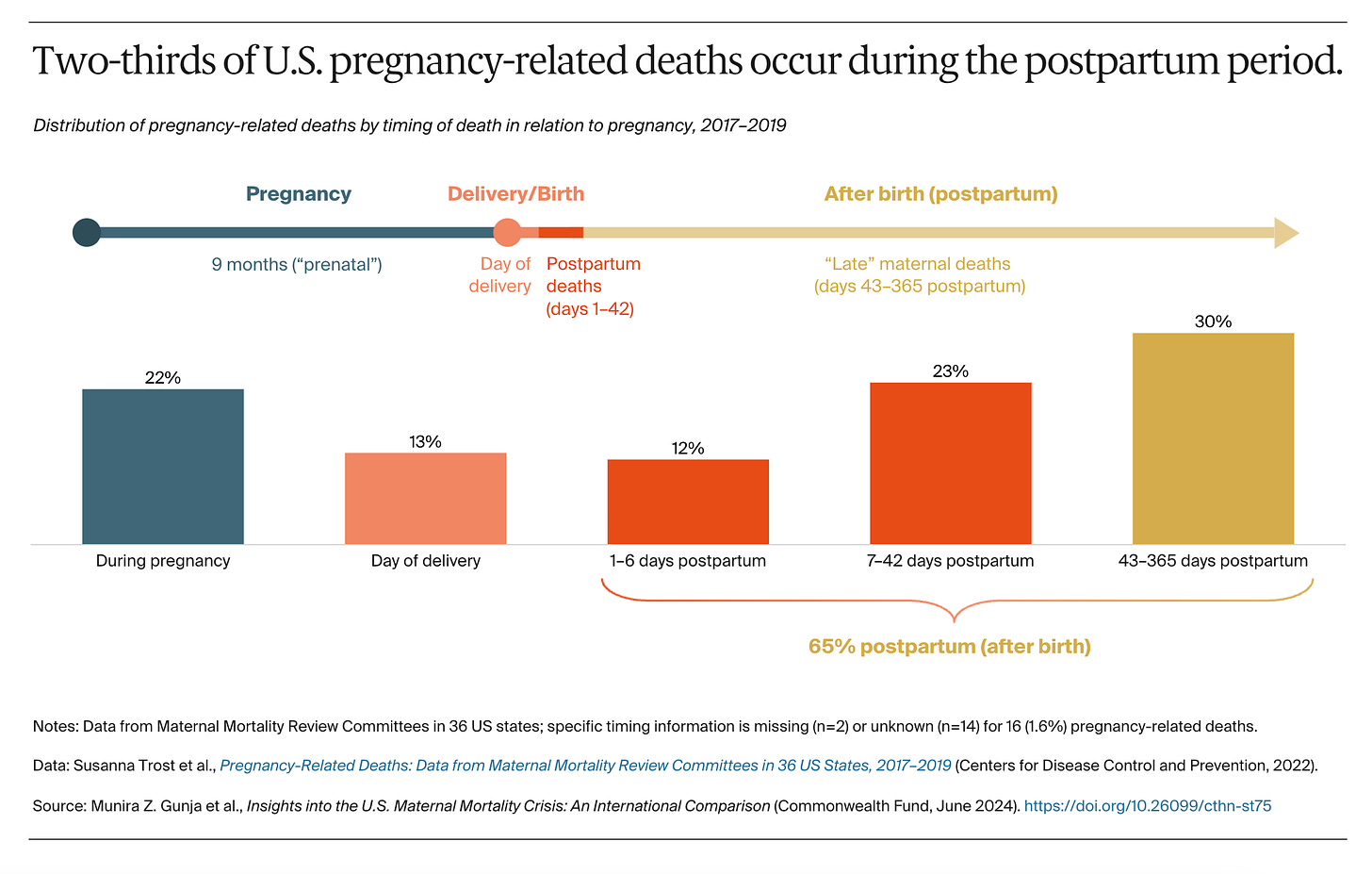

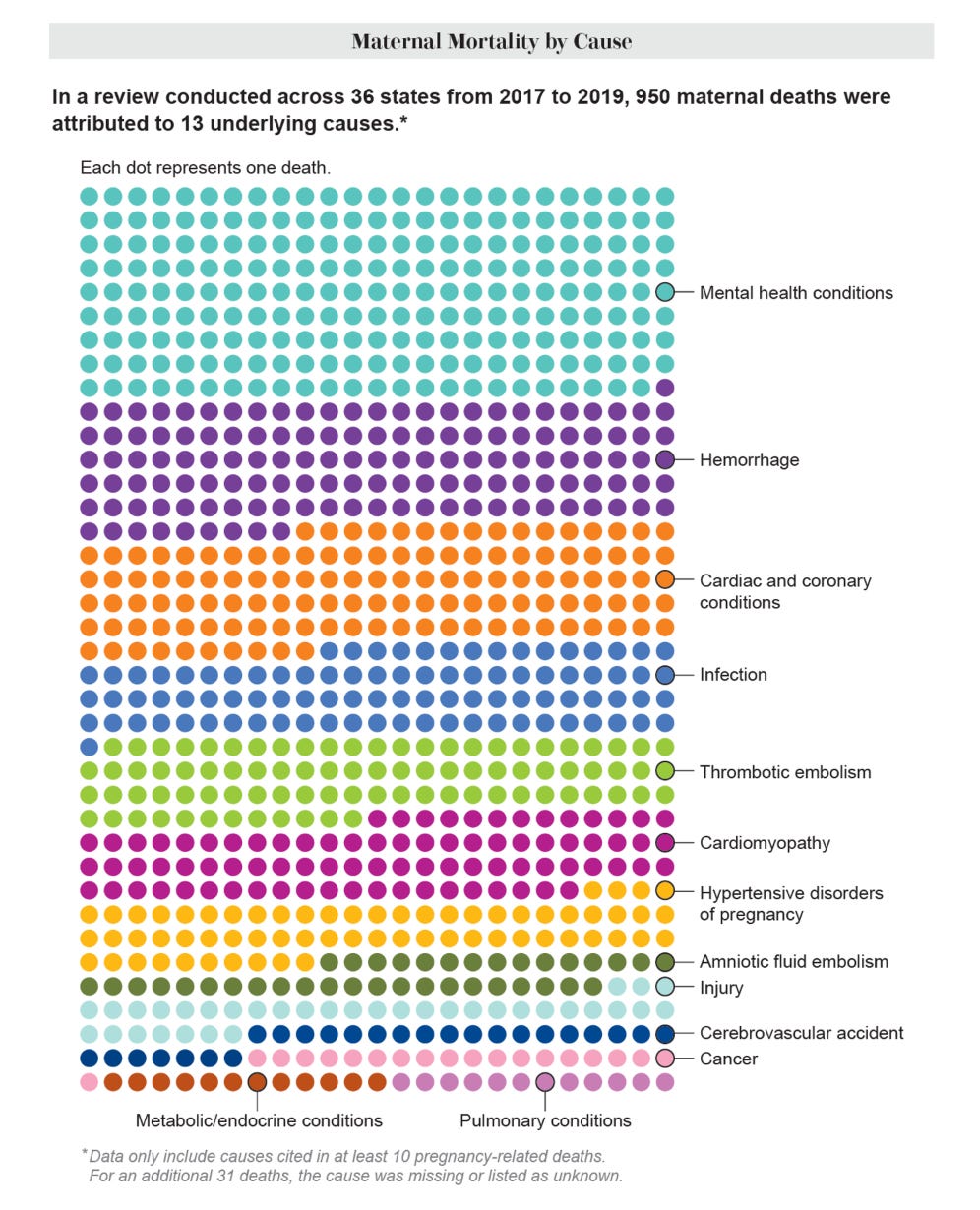

A striking feature of US maternal mortality is that two thirds of maternal deaths occur postpartum.

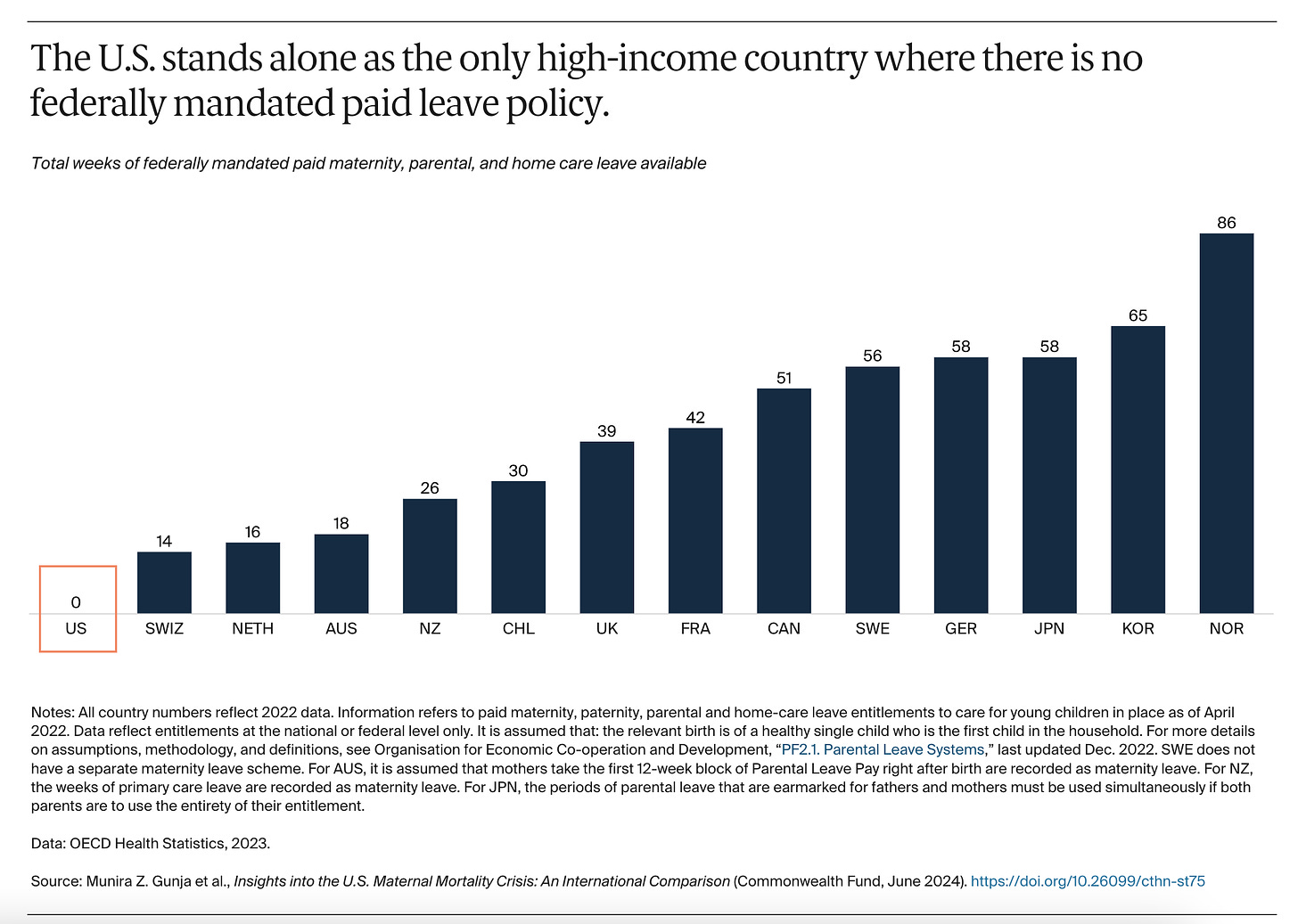

The US is alone amongst rich countries in offering mothers no statutory maternity leave.

Especially amongst white women a large share of mortality occurs after giving birth and is related to mental health issues.

Source: Scientific American

But is the picture painted by the data true to reality on the ground?

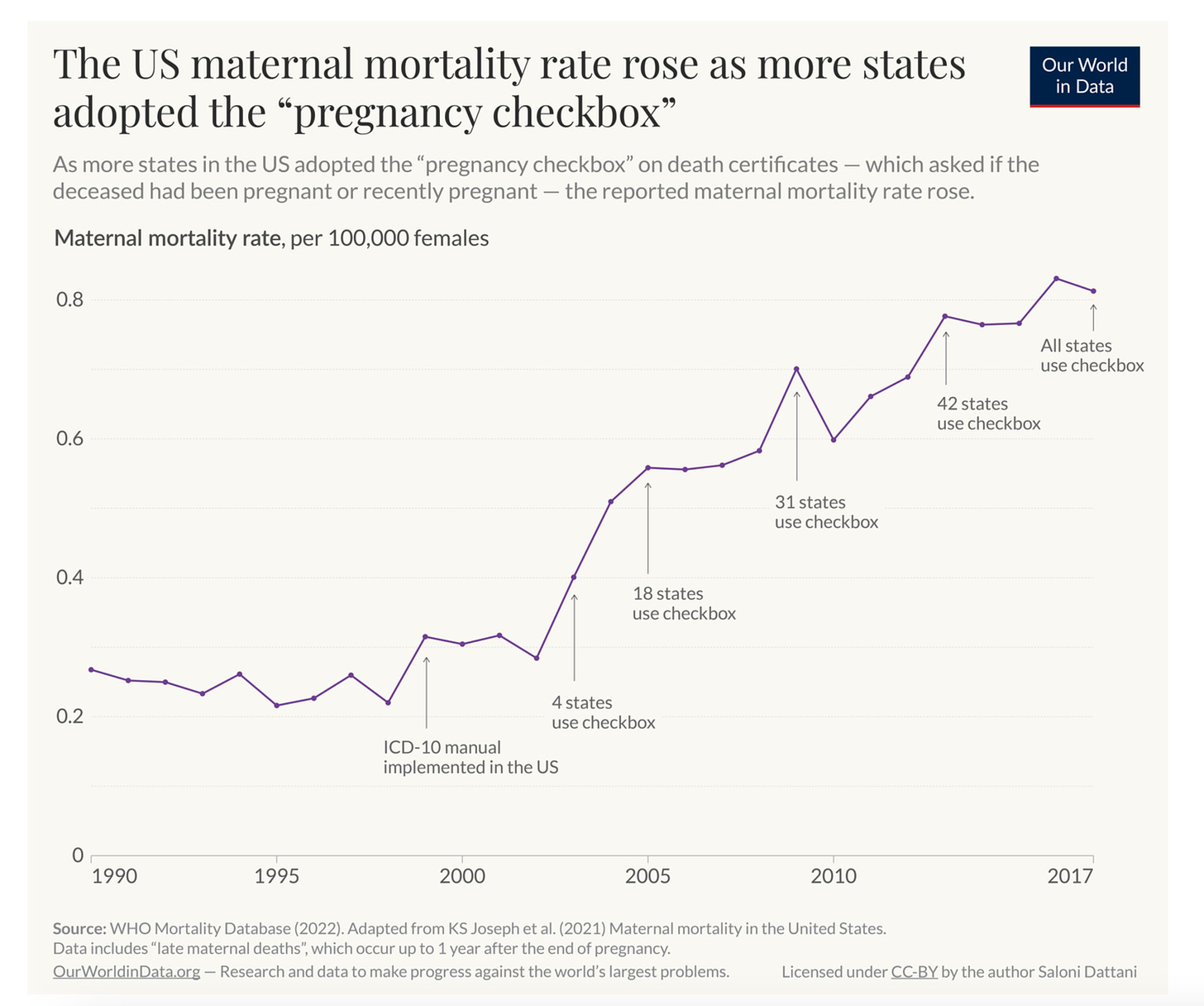

At least some inside the US health care system doubt it. Several teams of scholars has done assiduous work on the data and they find that the increasing rate is most likely an artefact of a change in reporting system. They doubt not only the trend but also the overall rate of mortality. The conclusion of their research is that the mortality rate is half the figure published by CDC i.e. closer to 10 per 100k live births than 22.3.

This has led Our World in Data and NPR to publish reports questioning the crisis narrative.

Source: Our World in Data

Though these seem like plausible and good faith efforts to set the record straight, the revisions are, themselves, not generally accepted. CDC rebuts the claims. Other scholars point out that the methods used by the revisionist investigators tend to understate mortality.

And if the data reporting issues are, indeed, real, what does that tell us about the system? I was left scratching my head at the idea that introducing an additional question on pregnancy, to a presumably controlled process of hospital management could introduce so much noise. If we cannot count on a simple box to be ticked the right way, what else is also being misreported? If a form records the surreal fact of the death of a pregnant 70 year old, how do we know whether it is the pregnancy, or the age that has been misrecorded?

Such surreal questions aside, three things do not seem in dispute.

Even on the revised data the maternal mortality rate in the United States is worse than in every comparable rich country.

Even if maternal mortality is not increasing in the United States, it is not improving as it is in most other advanced economies. If one assumes that a health care system should be seeking to improve and any maternal death in a rich society is a disaster, this is, by itself, evidence for serious malfunction. Plateauing at a high level of mortality is a sign of something being quite fundamentally wrong.

Finally, no one doubts that there are shocking disparities in maternal mortality along lines of race that are a blight on American society and call into question any notion of belonging to a community of fate.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. In an exciting new initiative we have launched a Chinese edition of Chartbook. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates. I keep them as low as substack allows, to ensure that supporting Chartbook costs no more than a single cup of Starbucks per month. If you can swing it, your contribution would be much appreciated.

Thank you for highlighting this. I am a pediatrician with a degree in health services research. Hoping this is a safe space, I will admit to some despair, accumulating over the past twenty years, related to how irrelevant my advanced training in cost-effectiveness and health outcomes across systems has been to health care practice and operations. There is nowhere this dynamic has been more clear than in the question of maternal health in the United States.

I recently worked in one of the ten largest urban areas of the US, in a major academic children’s hospital, half a block down the street from a major academic adult hospital with a labor a delivery ward amongst the most technologically sophisticated in the world. And I will never forget that my colleagues were called to the room of one of our newborn patients not for the infant but because her mother had been “found down” in the room. This new mother became a statistic. And her daughter will grow up motherless.

There are few, if any, interventions more societally cost-effective than saving the life of a mother. There are few, if any, interventions more ethically profound than saving the life of a mother, the existence of a family.

Our macro-level statistics, in health care and in economics, often mask these profound differences in how our fellow citizens, how our communities, are living. As you wrote so eloquently, it calls “into question any notion of belonging to a community of fate.”

Is it any wonder that when those of us who care, who have studied, who know these realities, who work in the most prestigious systems designed to help prevent these tragedies, and who are therefore supposedly in positions of relative power, are, in reality, unable to make a difference . . . Is it any wonder that those we would hope to vote with us are losing faith that we can actually make their lives . . . Better? A profound moral and material question of our age.

It is both chronic and becoming more acute. However, nobody of influence and authority cares.