In his speech at the 1973 Annual Meetings, World Bank President Robert McNamara coined the term “absolute poverty,” describing it as “a condition of life so degrading as to insult human dignity and yet a condition of life so common as to be the lot of some 40% of the peoples of the developing countries.” He then posed a difficult question: “And are not we who tolerate such poverty, when it is within our power to reduce the number afflicted by it, failing to fulfill the fundamental obligations accepted by civilized [people] since the beginning of time?” This defining speech solidified the Bank’s new goals at that moment: to accelerate economic growth and to reduce poverty.

Genoni Larkner 2024 World Bank

That was 1973. Half a century later, what a wave of publications the World Bank tell us is that the fight against absolute poverty faces a new and urgent historic challenge.

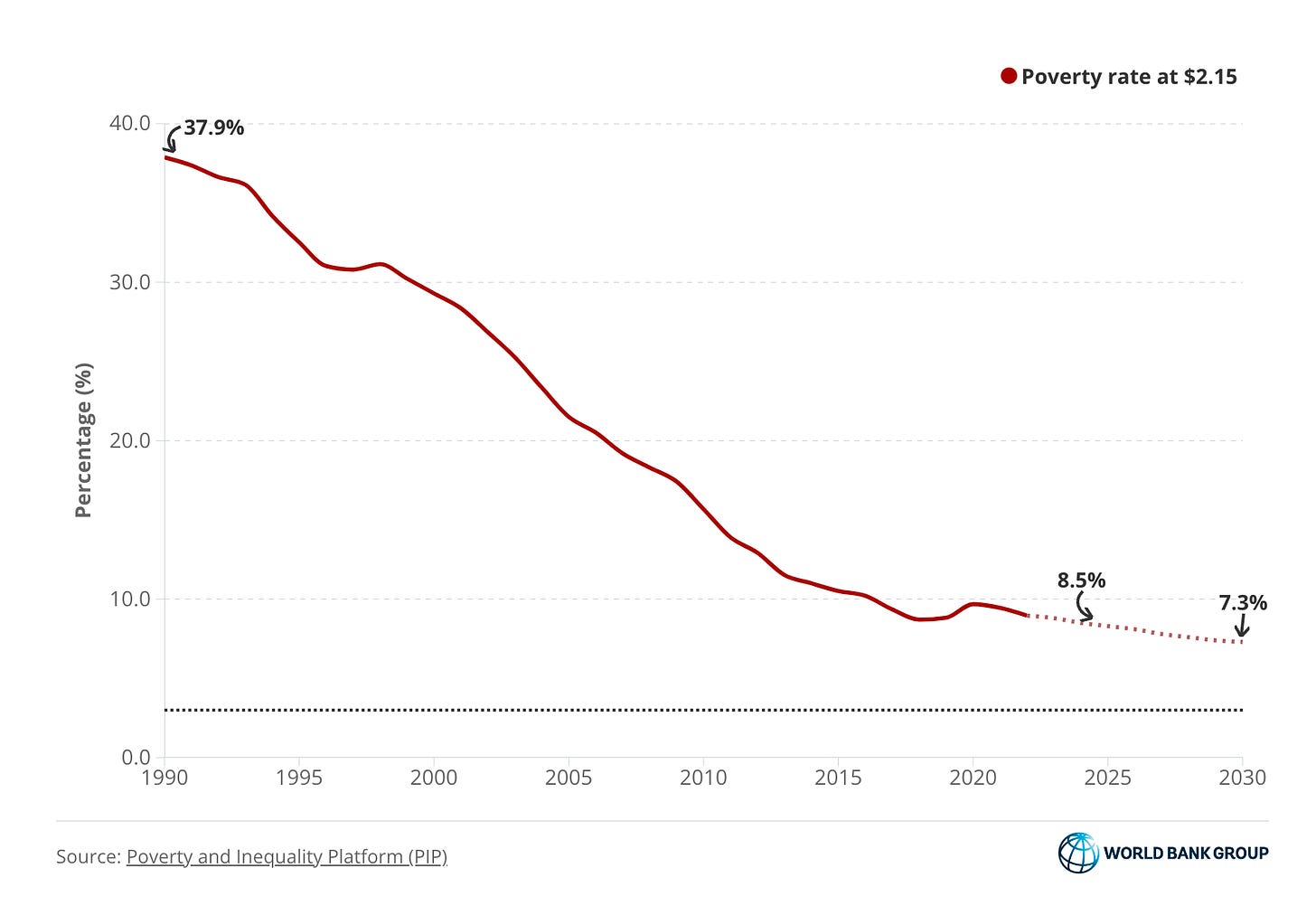

From the 1990s onwards economic development brought giant progress towards the goal of ending absolute poverty. But that progress stopped ten years ago.

Since 2015, the push to raise the world’s population out of the direst deprivation, has stagnated. As the World Bank authors acknowledge, we are “facing a lost decade in the fight against global poverty”.

Not only has there been little progress since 2015. But the onset of what the World Bank Poverty, Prosperity and Plant Report dubs the “polycrisis”, is putting further progress even further out of reach. As a blog post amplified:

We are facing a series of overlapping and interconnected crises that are impacting lives and livelihoods almost everywhere. The combined effects of slow economic growth, rising conflict and fragility, persistent inequality, and extreme weather-related events have sent shockwaves across the globe. High-income economies are showing signs of resilience, but the outlook for low-income economies and fragile countries remains deeply troubling.

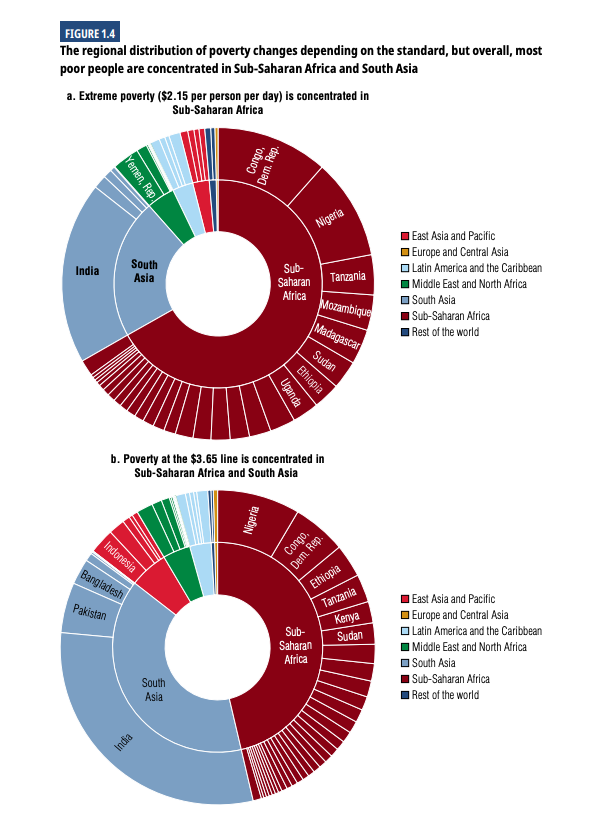

Just a decade ago, we had cause for more optimism. There was significant progress in sustainable development between 1990 and 2015, with more than a billion people lifted out of extreme poverty. This was a monumental achievement, driven primarily by strong economic growth in China and India, and it brought the wealthiest and least-well off economies closer in income levels. Yet, what seemed like a clear path to complete poverty eradication has since faded. … global poverty rates have only now gone back down to pre-pandemic levels, with forecasts indicating a trajectory for the coming years that is dismal at best. Almost half the world’s population—around 3.5 billion people—is living on less than $6.85 a day, the poverty line for upper-middle-income countries. At a more extreme level, almost 700 million people are living on less than $2.15 a day, the poverty line for low-income countries. Extreme poverty has become increasingly concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa or places affected by conflict and fragility.

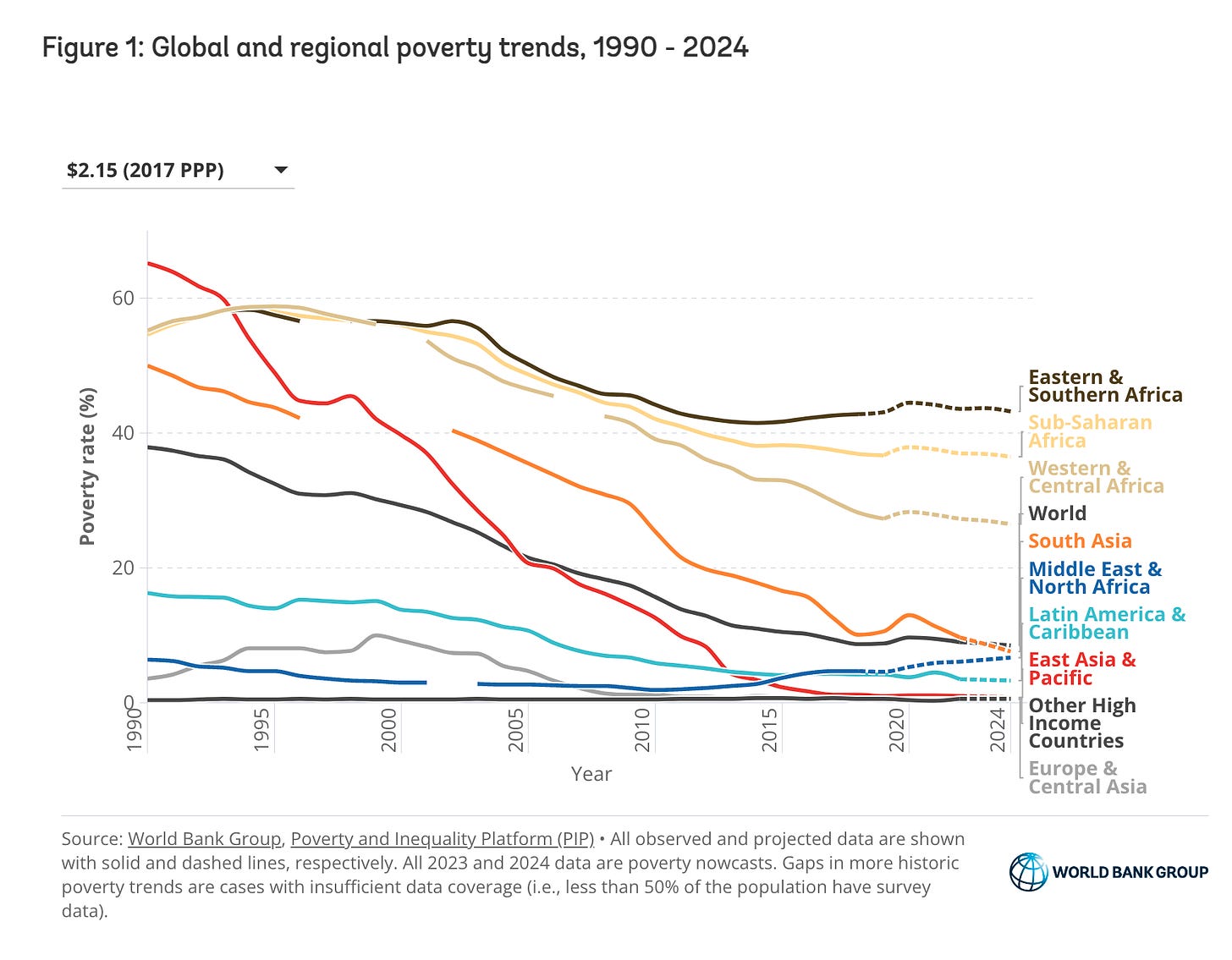

Once we break down the global data, the regional disparities are stark. If we focus on the most serious absolute poverty, the dynamics in the global number is driven by the relative movement of Asia and Africa.

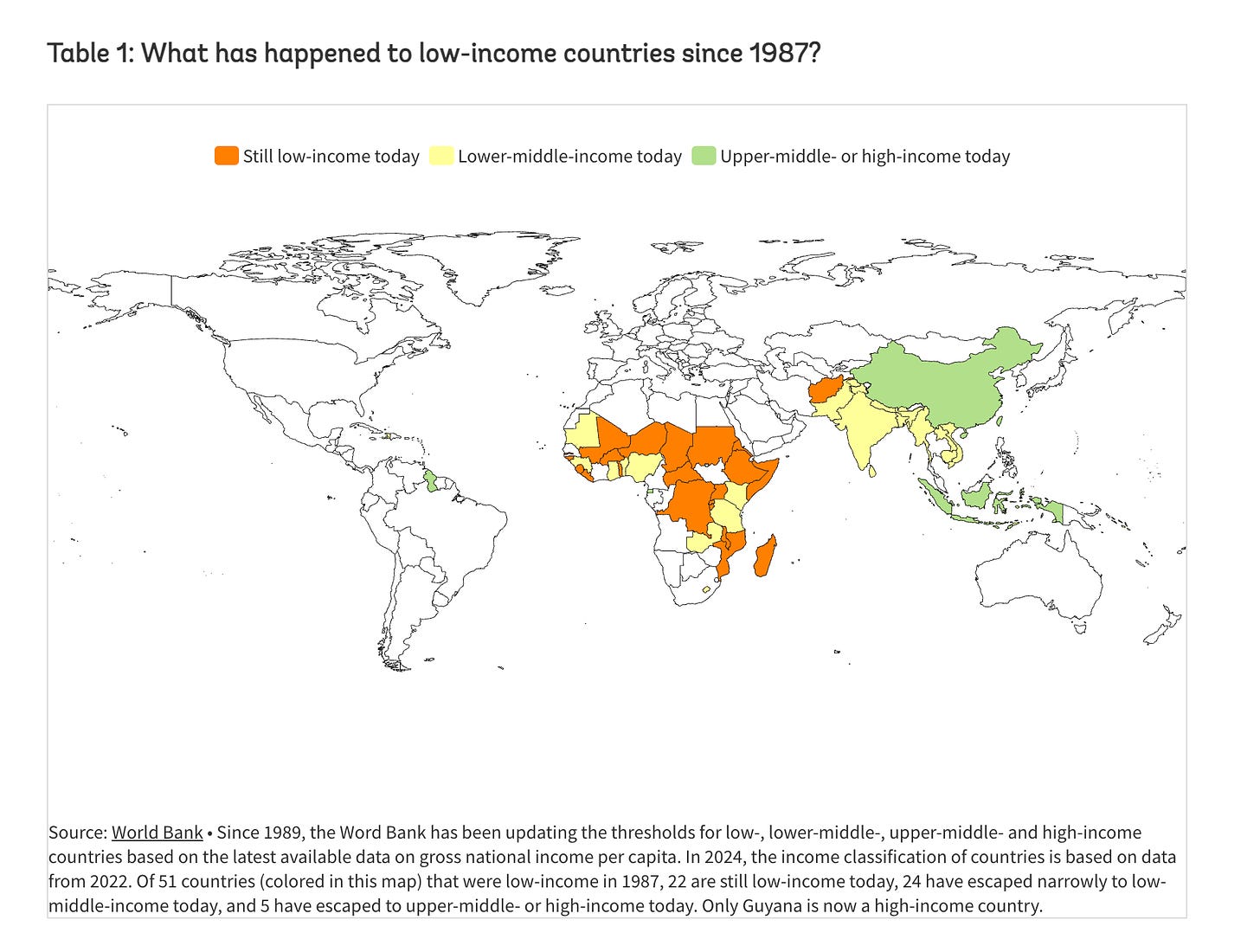

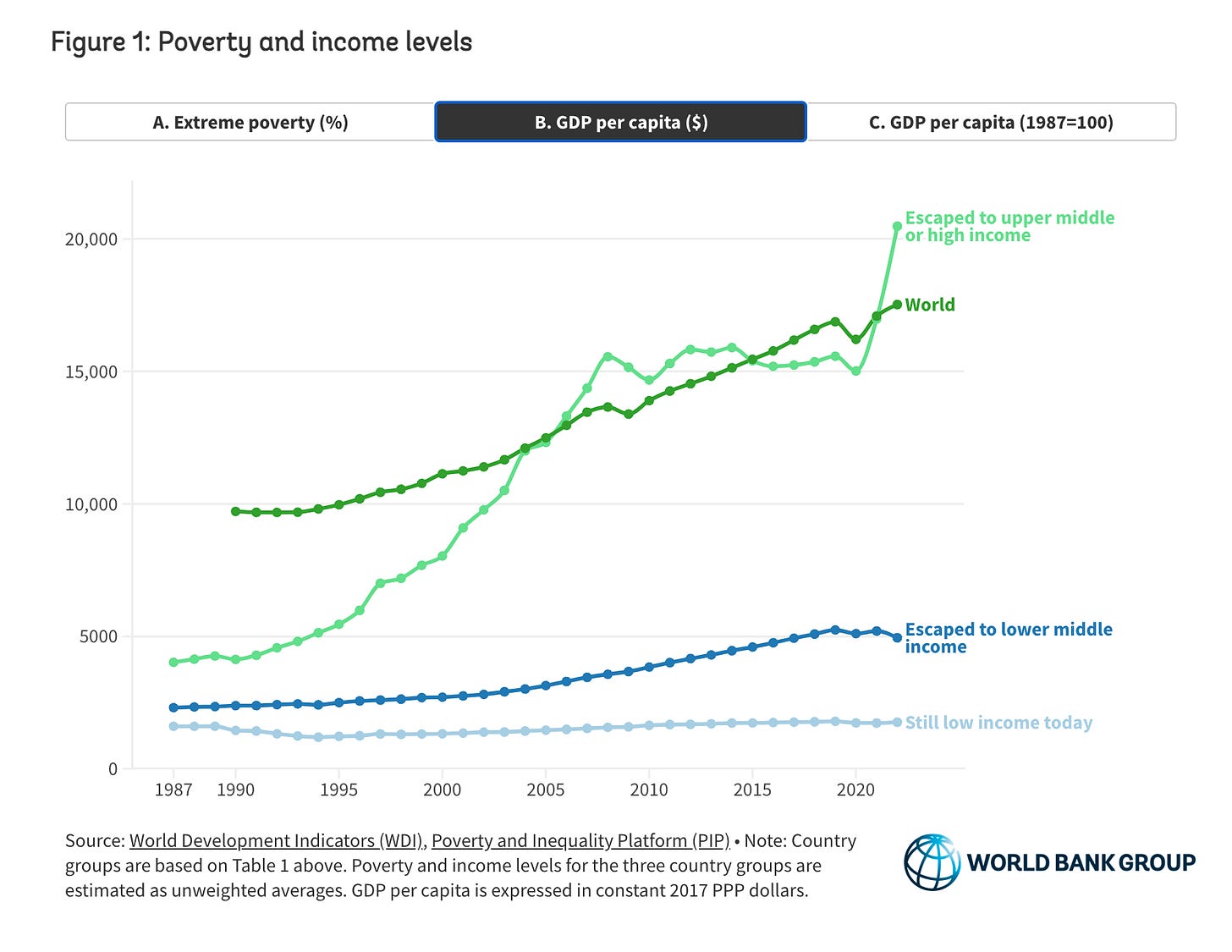

One way to make this more concrete is to look at individual countries. In 1987 there were 51 very low-income countries spread across Africa and Asia. Since then, 29 of those very poor countries have grown out of poverty, joining the ranks of the middle-income countries. Twenty-two countries remain profoundly underdeveloped. One is Afghanistan, the other 21 are all in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Whilst the rest of the world has grown, overwhelmingly African low-income countries have seen no measurable progress in per capita income for half a century.

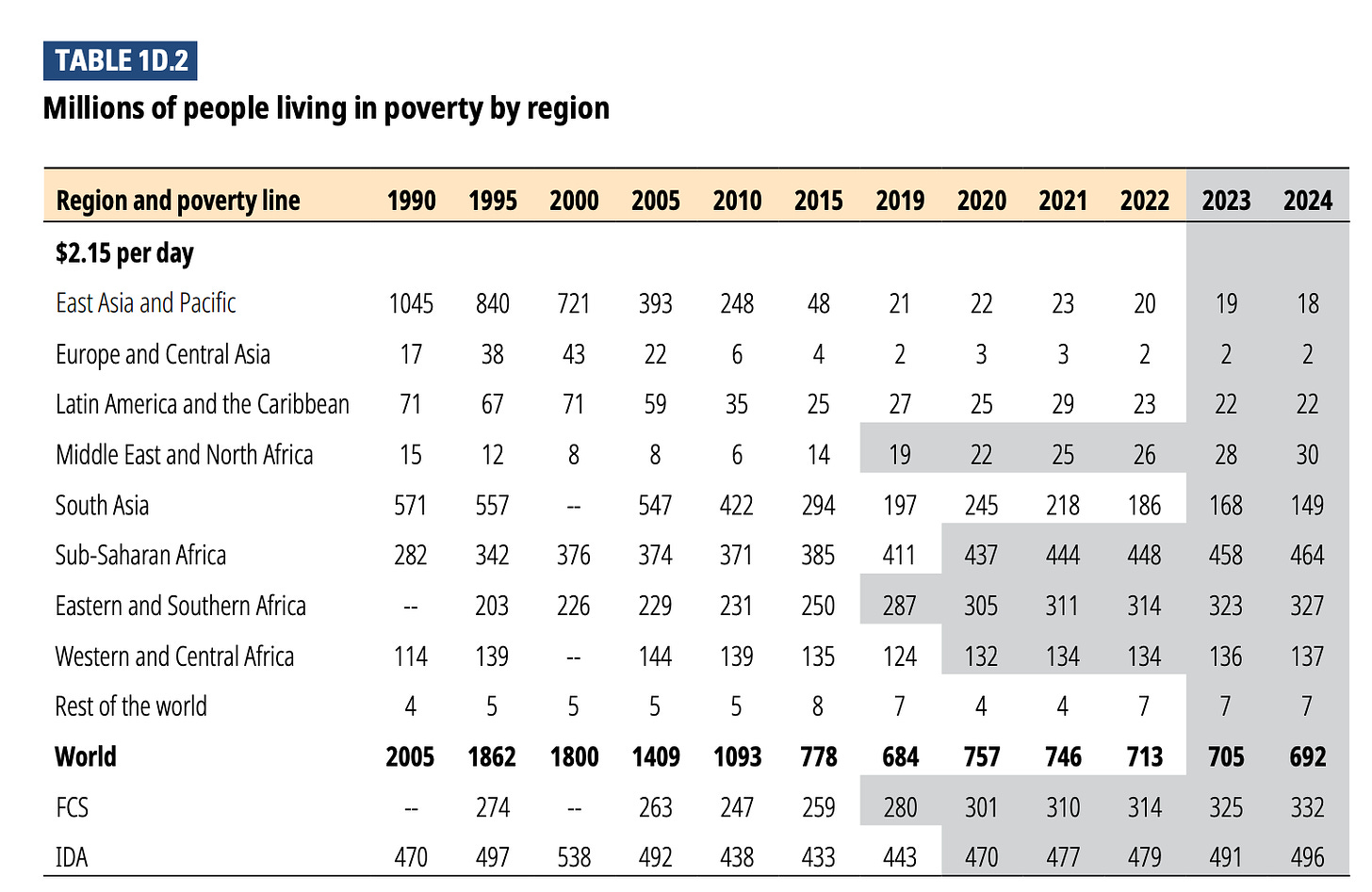

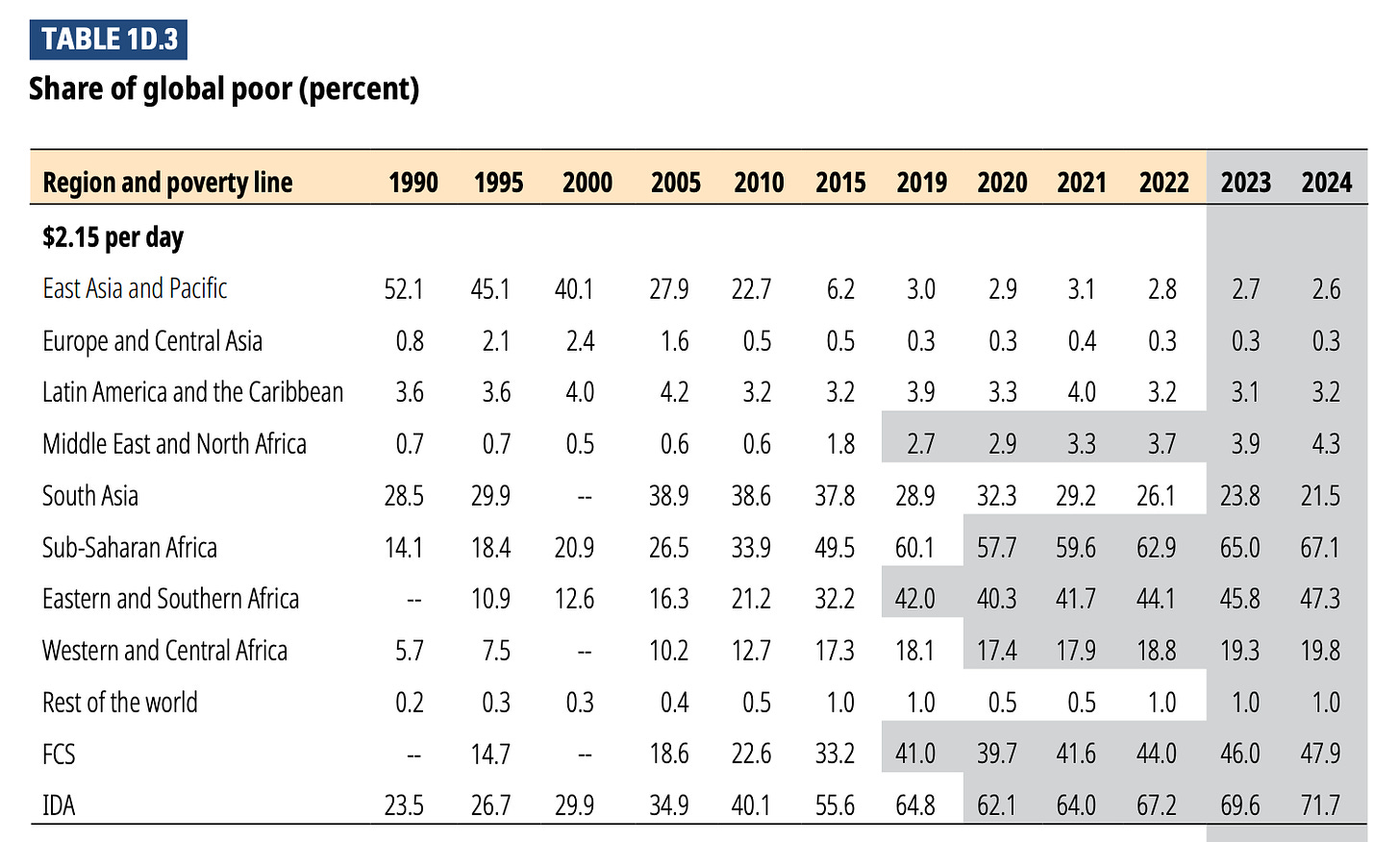

Moving from national economies to look at the number of poor people: Whilst the share of people living below the $2.15 per day threshold of absolute poverty has declined across the world. And whilst the number of people in absolute poverty across Asia has plunged. The number of people living in absolute poverty in Sub Saharan Africa has surged.

Until 2013, global extreme poverty reduction was led by China’s rapid economic growth, which lifted more than 800 million people out of extreme poverty over three decades. Between 1990 and 2024, the rest of East Asia and Pacific also made remarkable progress, with 210 million people exiting extreme poverty during this period. Extreme poverty also fell significantly in South Asia … Although the extreme poverty rate in Sub-Saharan Africa has fallen over the past three decades, it did so at much slower rates than in other regions, and the number of people living in extreme poverty in the region has come fairly close to doubling—rising from 282 million in 1990 to 464 million in 2024. Similarly, in the Middle East and North Africa, the number of people living in extreme poverty doubled from 15 million in 1990 to 30 million in 2024. Extreme poverty in that region has surged since 2014, driven by fragility, conflict, and inflation.

There are now three times as many people in absolute poverty in Sub-Saharan African than in South Asia.

“In 1990, East Asia and Pacific had a higher poverty rate than Sub-Saharan Africa, and South Asia had rates similar to Sub-Saharan Africa.”

In 2000, only one-quarter of the extreme poor were living in a country in Sub-Saharan Africa or in a country in fragile and conflict-affected situations (FCS). By 2014, every second person in extreme poverty lived in either Sub-Saharan Africa or in FCS. The share of extreme poor in FCS in Sub-Saharan Africa then grew starkly in the late 2010s, driven by countries with large poor populations becoming fragile (for example, Niger or Nigeria). By 2024, the share of the extreme poor in Sub-Saharan Africa or FCS had increased to three-quarters, and 42 percent of the global extreme poor were in FCS in Sub-Saharan Africa.

As the World Bank continues:

In Sub-Saharan Africa, which is home to about half of the IDA countries, economic growth has neither been large enough nor inclusive enough to reduce poverty significantly, especially since 2015 (Wu et al. 2024). Between 1990 and 2022, GDP per capita in Sub-Saharan Africa only grew by 0.7 percent annually (compared with 1.6 percent for the world). GDP growth in IDA countries is forecast to strengthen in 2024–25 but remain weaker than in the decade before the pandemic (World Bank 2024d).

Nigeria is a case in point. On a country basis it has made the step from low-income country to low middle-income status and yet it is now home to the third largest number of absolutely poor people in the world, after India and DRC. The tourist destination Tanzania, is fourth on the list of countries with the largest number of people below the $2.15 per day line.

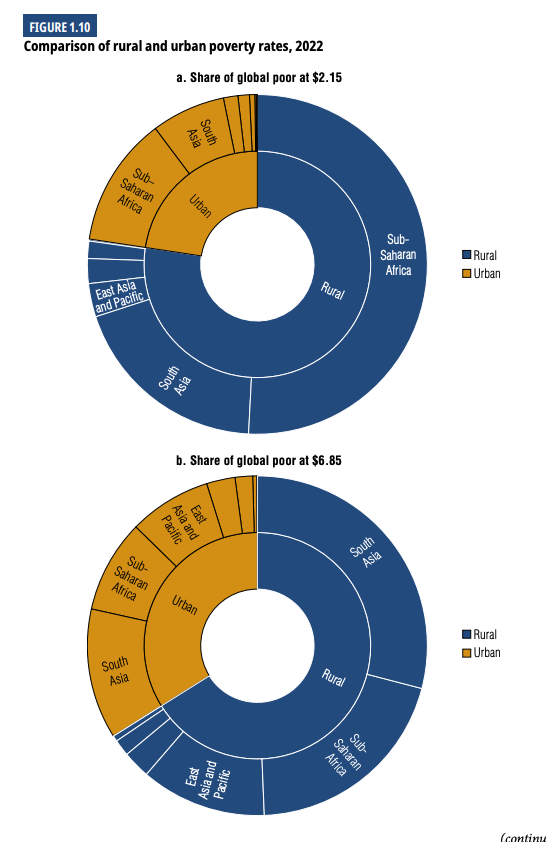

Across Africa, huge disparities of income between more favored urban locations and the countryside are common.

For example, in some parts of Namibia, an upper-middle-income country, over 30 percent of the population lives on less than $2.15. The poorest areas in the country are sparsely populated and not well connected to the rest of the country. In South Africa, also an upper-middle income country, the province Eastern Cape has a poverty rate of 36 percent, which is five times higher than the poverty rate in Western Cape and Gauteng and more similar to poverty rates in regions in Guinea-Bissau or Lesotho. In the capital region of Chad, only 3 percent of the population lives on less than $2.15, while the poverty rate of the whole country is 31 percent.

In general it is true that extreme poverty is most prevalent in rural rather than urban areas. As difficult as conditions may be in urban slums, it is the prospect of improvement that draws tens of millions from the countryside to the city.

More than three-quarters of the global extreme poor lived in rural areas in 2022, and half of the global extreme poor lived in rural Sub-Saharan Africa alone. In nearly all regions, the rate of extreme poverty is higher in rural areas than urban areas, with rural poverty at 16 percent and urban poverty at 5 percent for the world as a whole. The difference between rural and urban poverty is most pronounced in Sub-Saharan Africa, where the rural poverty rate is 46 percent and the urban poverty rate is 20 percent.

The causes of poverty are multiple and compound each other.

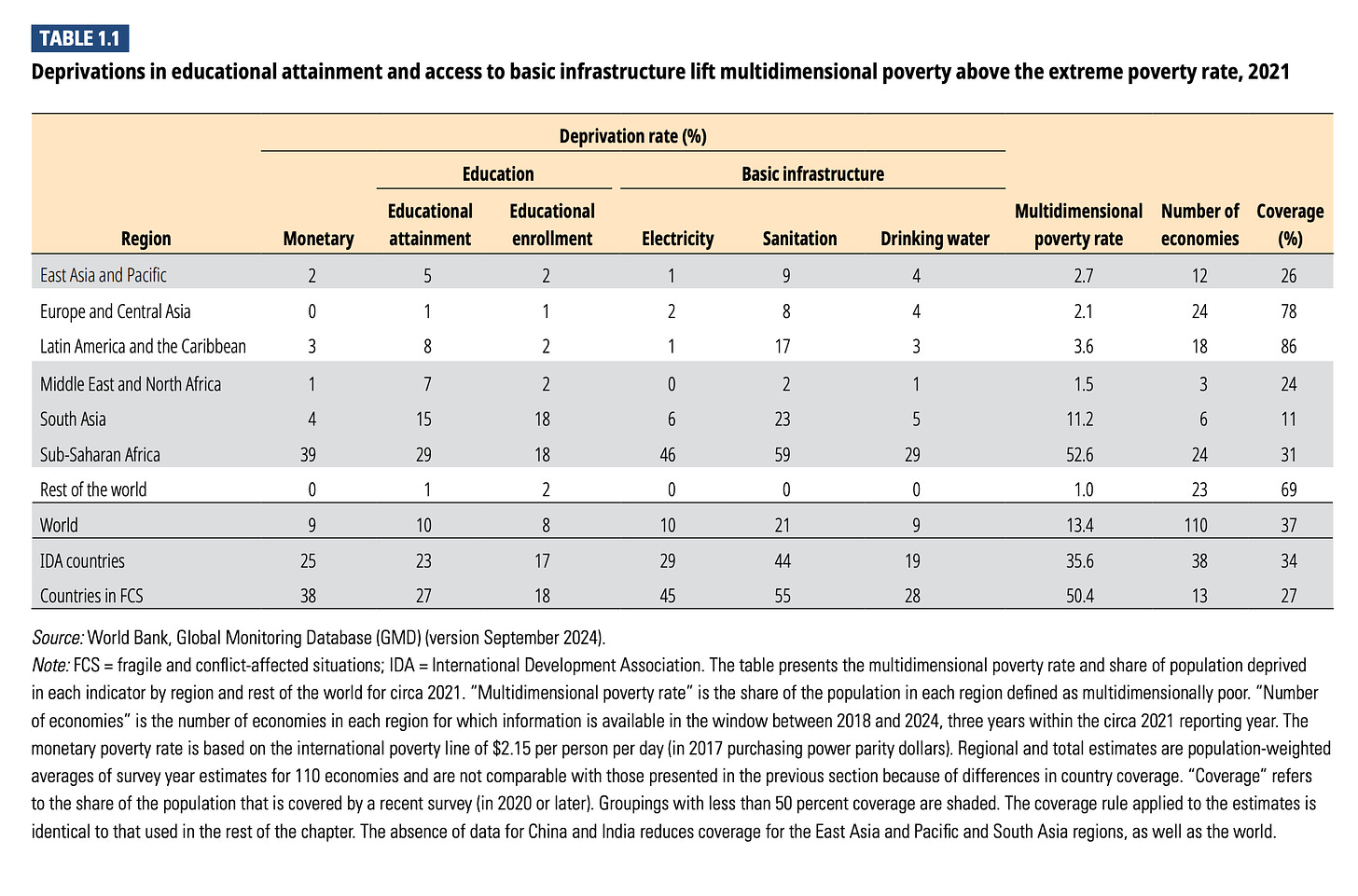

About one-half of the people in Sub-Saharan Africa and FCS countries lack electricity or sanitation. Large education gaps also persist. In 20 low-income countries with available data, more than 90 percent of children cannot read or understand a basic text by the end of primary school. Yet, investments in education in low-income countries remain very low. In 2021, the average low-income country spent only $54 per student per year, compared with more than $8,500 in the typical high-income country. In some of the poorest countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, only 20 percent of respondents surpass the education of their parents, compared with 80 percent in East Asia.

In the poorest countries, poverty and deprivation are multi-factorial and, if anything, purely monetary measures such as the $2.15 standard, understate the level of deprivation. In Sub-Saharan Africa the lack of basic electricity and sanitation infrastructure is even more pronounced than the monetary measure would suggest.

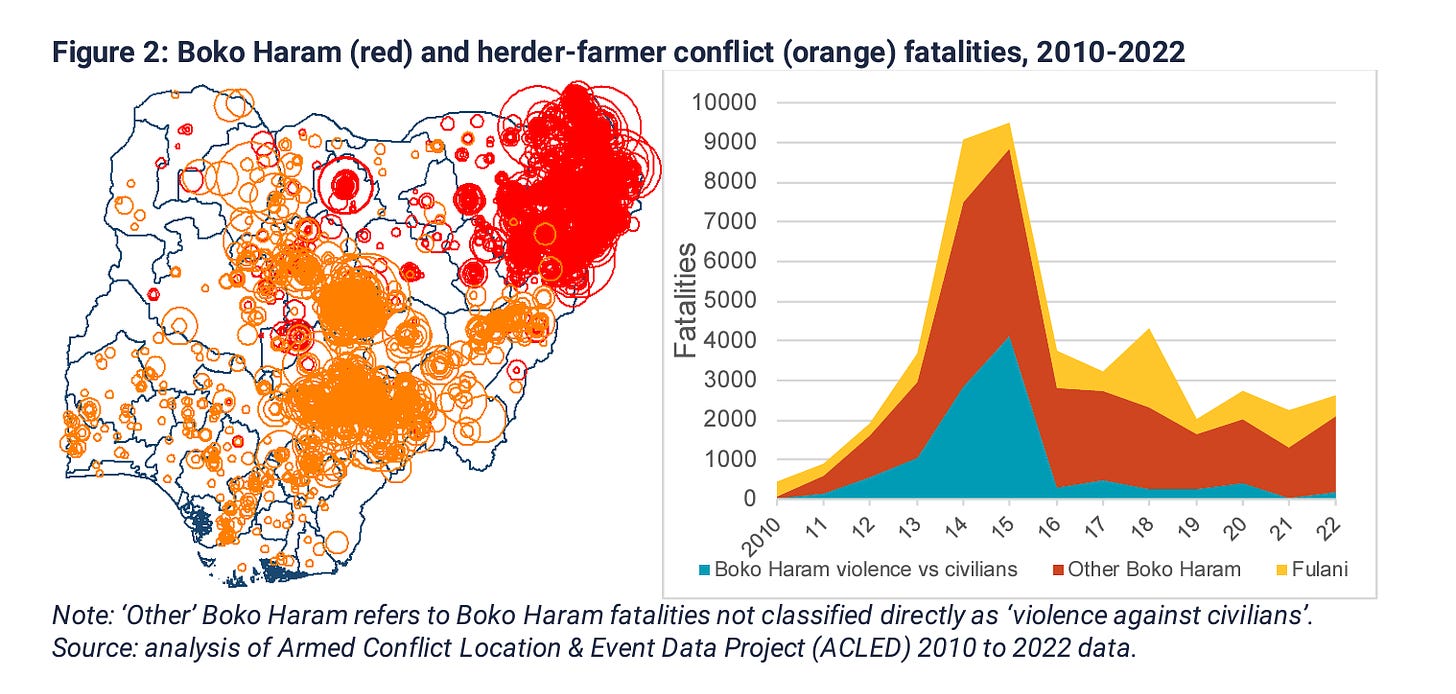

So this is the upshot of development trends of the last half century. Thanks to Asia’s remarkable growth, absolute poverty is no longer a general global condition. It is now concentrated in a belt running across the breadth of West Africa, the Sahel, Central and Eastern Africa and extending up to the Horn of Africa. Across this vast region a rapidly growing population that will soon number more than half a billion, struggle to survive amidst increasingly harsh and unpredictable environmental conditions, more hampered than helped by states that fail to provide even basic infrastructure and services and where as one recent study of Nigeria has shown, inter-communal violence is amplified by environmental shocks.

Conflict, violence and political instability make either public or private action to escape poverty impossible. As the World Bank comments.

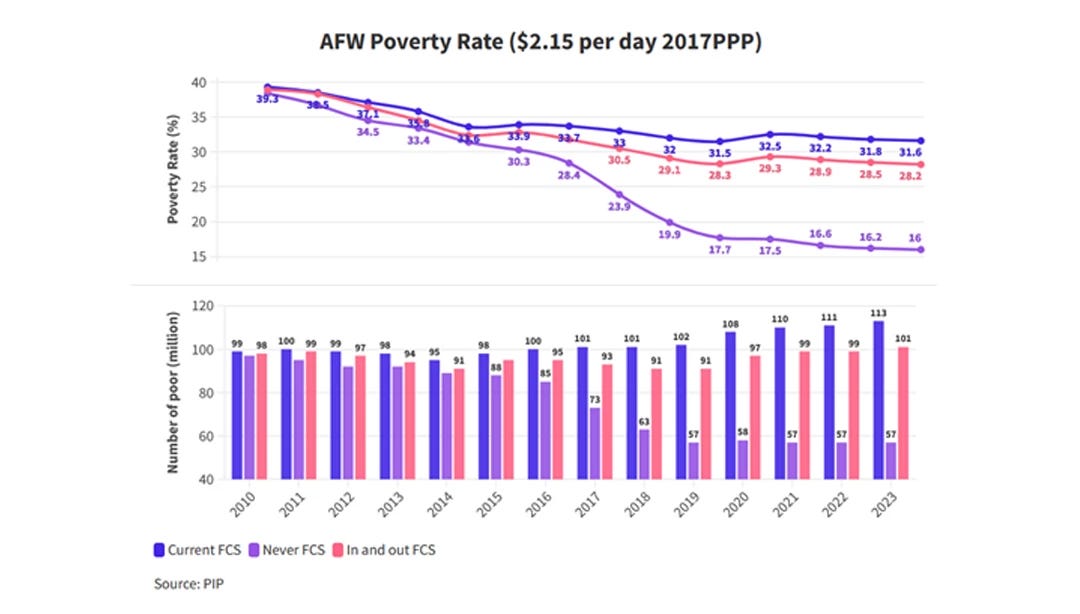

The importance of stability for future poverty reduction can be seen from the graph below, prepared for Western and Central Africa. Countries that managed to avoid fragility (Benin, Cabo Verde, Gabon, Ghana, Equatorial Guinea and Senegal) managed to steadily reduce poverty. Relative to countries that are presently fragile, or that moved in and out of fragility, stable countries reduced poverty by an additional 15 to 20 percentage points. Stability, by the way, goes beyond an ability to maintain peace. Macro-fiscal and debt sustainability are equally critical, as Ghana which recently defaulted on its external debt unfortunately shows. Poverty (at $ 2.15) increased from 25% in 2020 to 33% in 2023.

The implication is clear. Future poverty reduction will increasingly be premised on the ability to ensure stability, as stability is a precondition for economic growth and poverty reduction. In a world in which conflict and instability are on the rise, and debt distress is rising, this is a sobering realization and bad news for the global community’s ability to eradicate poverty anytime soon.

It is a long way from the civilizational language espoused by McNamara half a century ago.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. In an exciting new initiative we have launched a Chinese edition of Chartbook. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates. I keep them as low as substack allows, to ensure that supporting Chartbook costs no more than a single cup of Starbucks per month. If you can swing it, your contribution would be much appreciated.

Access to electricity spurs stability and innovation

Excellent post Mr. Tooze