Chartbook 328 An economics Nobel for Biden's neocon moment. On AJR's "Whig" philosophy of history.

Source: Washington Post

The regular email that dropped into the inbox yesterday from Heather Boushey of the Council of Economic Advisers, who doubles as Chief Economist to the Invest in America Cabinet, featured as #3 the following item:

Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson (AJR) were awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in economics for their work showing how important societal institutions are for economic prosperity. Their research on issues such as inequality and worker bargaining power have informed the President and Vice President’s economic agenda to grow the economy from the middle out—and they’ve shown how we can build a cleaner economy and grow the economy and invest in place-based innovation and deliver good jobs.

The second links takes you to a similarly celebratory statement by Biden’s CEA Chair Jared Bernstein, which reads as follows:

The Council of Economic Advisers warmly congratulates the three winners of this year’s Nobel Prize in Economics: Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson. As the committee noted, their work has “demonstrated the importance of societal institutions for a country’s prosperity. Societies with a poor rule of law and institutions that exploit the population do not generate growth or change for the better.” Through their many papers and books including Why Nations Fail and Power and Progress, these economists have gone well beyond standard analysis of supply and demand, elevating the role of institutions, power, inclusivity, and exploitation in understanding cross-country differences in economic outcomes. Such an expansion of the scope of what’s fair game for economic analysis has had real world implications for our Administration’s policy agenda. The work of these newly-minted Nobelists has significantly informed CEA’s analysis, in areas such as inequality, worker bargaining power, race, gender, climate, and pathways to opportunity. We are thrilled to see such important, pathbreaking, historically-grounded, and timely work get the credit and acknowledgement it deserves.

This made me curious. Is it normal for US administrations to comment on the Nobel prize in economics? It turns out that Bernstein also issued a statement back in 2023 to congratulate Claudia Goldin on her win.

Cameron Abadi and I have a made a bit of a tradition out of discussing the Nobel Prize in economics.

We did 2022 on bank runs. We discussed Goldin’s prize on the show last year and it was the second item also in this week’s episode. The first item is on China’s latest stimulus effort, on which more in a later post.

I must admit that before reading the Boushey and Bernstein comments, I had not made the connection between the work of AJR and Bidenomics. On reflection, I think it is very illuminating.

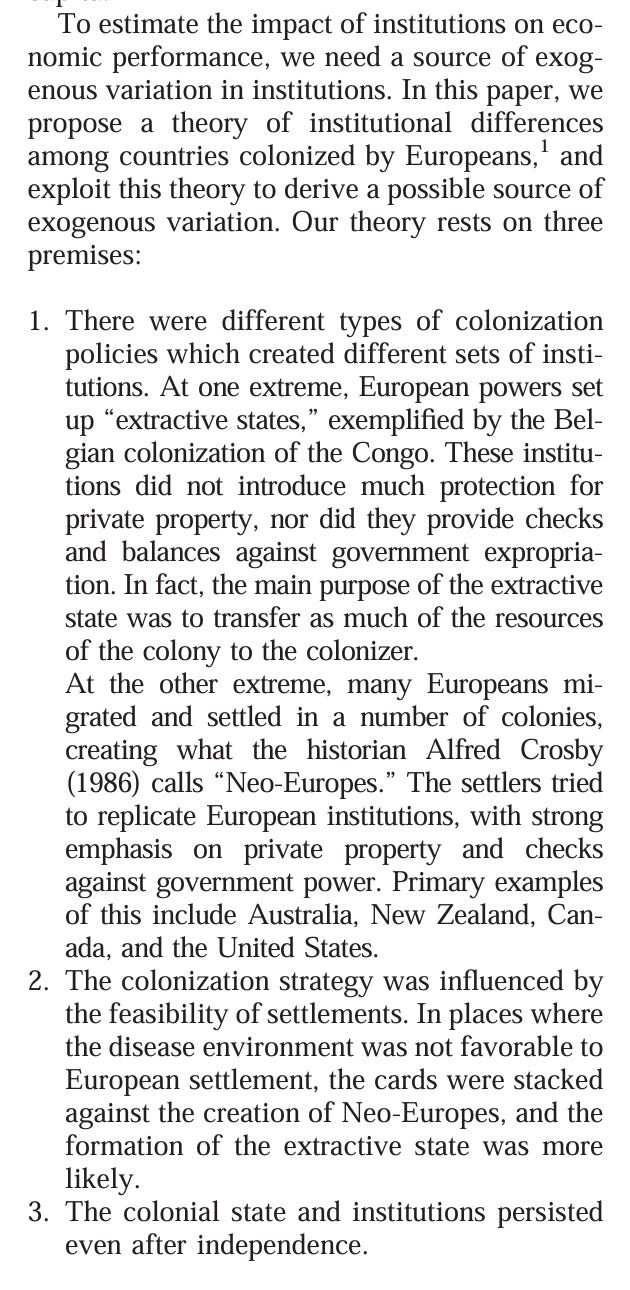

“The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development”, the paper for which AJR are are most widely cited and which forms the basis of their prize citation, dates to 2001. It is a very much a product of its time and at first glance it could seem to concern itself with questions that are quite remote from those of Bidenomics. Their aim is to explain the long-range and large-scale difference in per capita income that divided the world into “Global North” and “Global South”. They were motivated, in short, to explain the starting point for economies in the new era of globalization.

To an economist the vast and persistent differences between the Global North and the Global South are a puzzle. You would expect huge profits to be made by arbitraging the scarcity of capital and technology that those gaps imply. For such large differences to persist and develop, we need more complicated explanations. AJR see the large differences in GDP per capita as rooted in institutions. For those to provide a true explanation, however, they must themselves be exogenous i.e not path-dependently driven by the differences in income that we are seeking to explain. In the case of the 2001 paper, the exogenous variation is provided by disease burden and settler mortality in the regions that were subject to Western colonial assault. AJR’s argument is that permanent differences in institutions resulted from the reaction of the settlers to the environment (and later also the opportunities) that they encountered.

Already at this stage, a series of key aspects of their research agenda were clear: 1. institutions shape economic growth as much as economic growth shapes institutions. They are skeptical, therefore, of crude materialist or modernization theories, that see the influence running from technology and economics to institutions and do not allow for a reverse flow. 2. They are interested in history and in geography, but do not accept either as fate. Political choices are decisive. 3. Political choices have ultimately to be explained by struggles within elites and between elites and the populations they govern.

They will go on, as the Nobel citation explains, to combine an account of historical opportunities, provided by crises, with a study of elite dynamics and struggles between the population and the ruling elite. If this sounds like social science history you are not wrong. But because they operate in the sphere of economics it is often also cast in terms of models that formalize political economy in mathematical terms. To be honest it is not obvious what is gained by those exercises in formalization. But they are de rigeur in the discipline.

The general conclusion, however, is extremely familiar. Technology and capital accumulation are key to economic growth. They themselves are shaped by institutions. Those institutions are decided by politics. And the most propitious institutions for long-run economic growth driven by innovation, are institutions based on rights and freedom. This is Acemoglu writing in 2012:

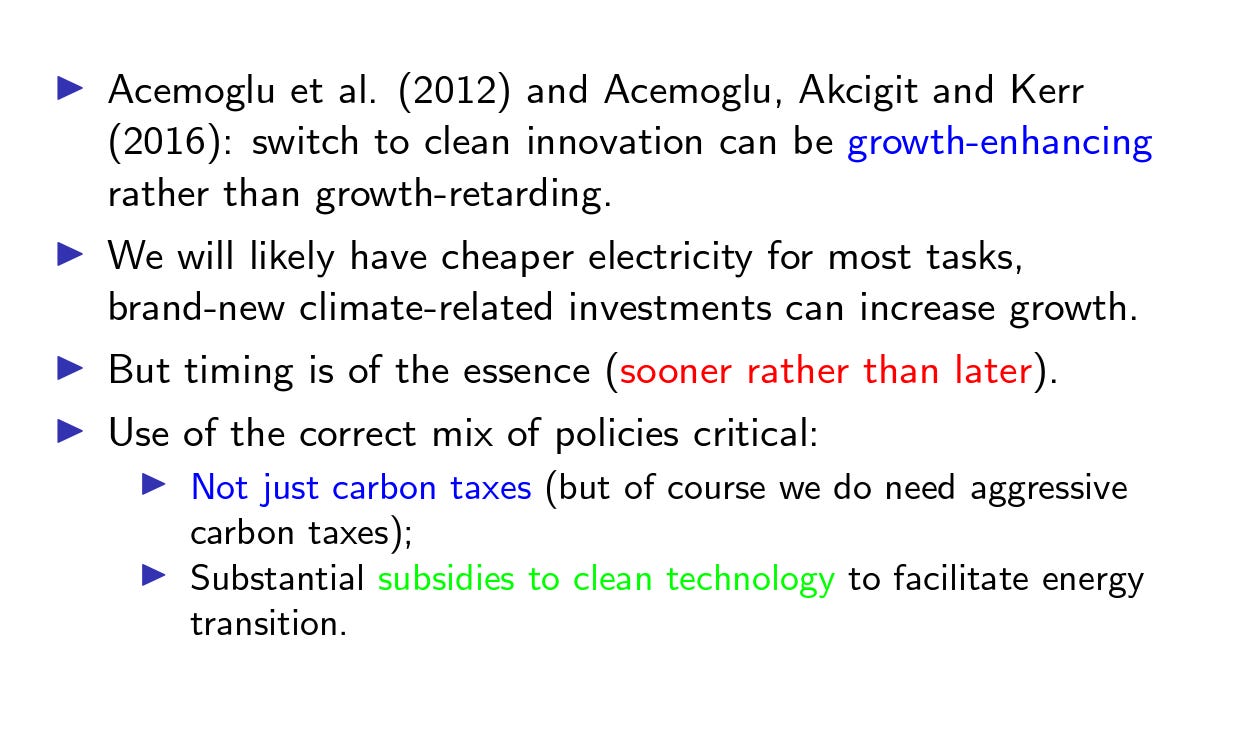

Beyond such sweeping vistas, their general interest in the political economy of growth went on to open up a series of studies on the political economy of innovation, investment and growth. Boushey cites Acemoglu’s work from the 2010s where he moved beyond the consensus amongst economists that focused on carbon pricing and carbon taxing to insist on the need to use policy to promote the development of clean energy technology, thus enabling more rapid switching to renewable energy.

Simon Johnson is engaged in industrial policy by way of Jump-Starting America.

Already in 2009 James Robinson was pleading for an empirical approach to industrial policy.

In this paper I discuss the role of industrial policy in development. I make five arguments. First, from a theoretical point of view there are good grounds for believing that industrial policy can play an important role in promoting development. Second, there certainly are examples where industrial policy has played this role. Third, for every such example there are others where industrial policy has been a failure and may even have impeded development. Fourth, the difference between these second and third cases rests in the politics of policy. Industrial policy has been successful when those with political power who have implemented the policy have either themselves directly wished for industrialization to succeed, or been forced to act in this way by the incentives generated by political institutions. These arguments imply that we need to stop thinking of normative industry policy and instead begin to develop a satisfactory positive approach if we are ever to help poor countries to industrialize.

Clearly, AJR’s work over the last quarter century fits well with the new tone and self-conception of economics in policy-making in Washington today. Though highly competent in technical terms, they are not debating the finer points of monetary economics or time series econometrics. They are interested in the interface between economics, politics, law and institutions.

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that leading economic advisors in the Biden administration see them as kindred spirits. After all, the prevailing tone around the White House in recent years has been described by Allison Schrager at Bloomberg as Yale Law School economics.

The figure for whom this quip was coined was Jake Sullivan, who has had a huge influence in setting the economic agenda of the administration. But as Greg Rosalksy at Planet Money argues, the point has wider application.

The head of President Biden’s CEA, Jared Bernstein, studied music and social work. He has no degree in economics. Some of Kamala Harris’ top economic advisers — from Brian Deese to Mike Pyle to Deanne Millison — are all lawyers. And on issues from free trade to immigration to tax policy to rent and price controls, both the Trump and Harris campaigns are throwing bedrock economic ideas in the trash can and embracing heterodox, populist ideas that might get you laughed at in economics courses. …. Even though the acolytes of the Yale Law School of Economics can be found on both sides of the political aisle, Schrager points out, they share a worldview. They are skeptical of free trade. They bash big business. They see the decline of manufacturing not as a natural evolution of the economy but as a policy catastrophe that needs fixing. They support industrial policy, or a more muscular role for the government in shaping industry with policies like tariffs and subsidies. They think a lot about dividing up the economic pie, Schrager says, and less about growing it. In all this, Schrager says, the Yale Law School of Economics rejects important ideas that have long dominated mainstream economics. …. The rise of the Yale Law School of Economics seems to say more about the political winds of our times and the declining popularity of economists and their ideas than anything. Free-market policies — sometimes called “neoliberalism” — are unpopular on both sides of the political aisle right now. Many blame it for widening inequality, the loss of manufacturing jobs and a host of related social ills. “I don't think a lot of economists would call themselves neoliberal, but a lot of ideas in economics do seem consistent with it,” Schrager says.

All this also means, that folks that I once described as gatekeepers - blue-blooded economists like Larry Summers, for instance - have lost influence. Not that AJR are outsiders. But their arguments are capacious enough to embrace a variety of disciplines, to address big question and yet also avoid being excessively technically prescriptive. Their writing is policy relevant without intruding on the discretion of the actual policymakers.

An open-mindedness about industrial policy and markets, helps to locate AJR in the current political space. But then, I thought of the question that Cam asked on the podcast about China, and then it really clicked. Though Boushey and Bernstein point to more technical essays, in the current moment, it is actually’s AJR’s macrohistorical narrative that is most in keeping with the mood in Washington.

If there is a red thread running through the Biden administration it is a return to a neoconservative framing of the relationship between the US and China. The President personally is enamored of the democracy v. autocracy framing. The more technical side of policy-making wagers that Western models of innovation and research will out perform their Chinese counterparts. The link between the two levels is the presumption that “free societies” produce more first-class patents and top-class STEM researchers. This is precisely what Acemoglu’s “rights revolution” promises.

The historical narrative developed by Acemoglu and Robinson in books like Why Nations Fail, is very much in tune with this kind of thinking. Encompassing inclusive institutions brought about by political revolutions replace extractive elitist institutions and thus set the incentives for investment and private accumulation. You might think, therefore, that China’s extraordinary growth under CCP rule would present an obstacle for their story. China’s growth is, after all, the greatest economic success of all time. As Mihir Sharma points out on Bloomberg, the entire problematic that has made AJR famous - why are some countries rich and others not - was framed in the late 1990s before China’s growth really took off. Now it seems that we have an answer to the question of development and it does not conform to their liberal script.

AJR do not simply dismiss the Chinese growth experience. As Acemoglu acknowledges:

China has posed a “bit of a challenge” to that argument, as Beijing has been “pouring investment” into the innovative fields of artificial intelligence and electric vehicles.

As Jeffrey Sachs pointed out in a review. It is very known that

… authoritarian political institutions, such as China's, can sometimes speed, rather than impede, technological inflows. China has proved itself highly effective at building large and complex infrastructure (such as ports, railways, fiber-optic cables, and highways) that complements industrial capital, and this infrastructure has attracted foreign private-sector capital and technology. And just like inclusive governments, authoritarian regimes often innovate in the military sector, with benefits then spilling over into the civilian economy. In South Korea and Taiwan, for example, public investments in military technology have helped seed civilian technologies.

The CCP in short acts as a non-liberal but inclusive regime. Its anti-corruption drives confirm this ambition and the work necessary to maintain that claim.

AJR are too realistic simply to deny these facts. But their claim is that though such structures can work for a while, in due course, if growth is to continue, there must be a transition.

China owes the growth it has so far achieved to the reforms of the 1980s and 1990s. In AJR’s terms these were a move towards a rights-based inclusive order. The slow down in recent year is then attributed to the failure to continue that reform momentum.

“Our analysis,” says Acemoglu, “is that China is experiencing growth under extractive institutions — under the authoritarian grip of the Communist Party, which has been able to monopolize power and mobilize resources at a scale that has allowed for a burst of economic growth starting from a very low base,” but it’s not sustainable because it doesn’t foster the degree of “creative destruction” that is so vital for innovation and higher incomes. “Sustained economic growth requires innovation,” the authors write, “and innovation cannot be decoupled from creative destruction, which replaces the old with the new in the economic realm and also destabilizes established power relations in politics.” “Unless China makes the transition to an economy based on creative destruction, its growth will not last,” argues Acemoglu. But can you imagine a 20-year-old college dropout in China being allowed to start a company that challenges a whole sector of state-owned Chinese companies funded by state-owned banks? he asks.

As Acemoglu remarked: “… my perspective is generally that these authoritarian regimes, for a variety of reasons, are going to have a harder time in achieving long-term, sustainable innovation outcomes,” he said.

In China itself the award of the prize to AJR was taken up by several intrepid economists, to argue for further a rebalancing in favor of the private sector.

Chinese economists called for institutional reforms after three US-based scholars won the Nobel Prize in economics with their research into how institutions shape the economic success of nations. “I think the conclusion of their work tells us that institutions are the most critical [to a country’s economic development]. This also has big implications for China’s way forward,” said prominent Chinese economist Xiang Songzuo, who added that the scholars’ conclusions were applicable to the China model. “Only by moving towards further marketising our economy, emphasising on the protection of intellectual property, private companies, fair market competition and upholding the spirit of entrepreneurship, can our economy attain sustainable growth, and our people can have higher incomes.” .. Nie Huihua, a professor at Renmin University in Beijing, said the research had “important insights” for China’s reforms and sustainable development. Nie referred to Beijing’s draft of a widely watched law concerning the promotion of the private sector, which was released on Thursday. The 77-article law would mark a “systemic approach” to address the sector’s problems and challenges, while helping create a stable, fair, transparent and predictable business environment, according to the National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Justice.

But tinkering with 77-article proposals from the NDRC does not do justice to the historical vision of Acemoglu and Robinson.

AJR’s agenda was once tightly formulated and specified. In recent years it has become increasingly wide-ranging. Whereas their aim at first was to insist on the exogenous importance of political institutions in economic development, increasingly their thinking has circled around the development of political institutions themselves and the interaction between politics, culture and the economy. As Cam and I discuss on the podcast, some of their arguments about culture are, frankly, hair-raising. With regard to China the issue they take to be at stake is the influence of Confucianism on Chinese institutions and, specifically, the prospects for the “rights revolution” and thus for innovation and long-run growth.

On the whole, their approach is non-dogmatic. Confucianism, they insist, offers many possibilities for the development of political culture and institutions. But for Acemoglu and Robinson what this entails is greater militancy. A case in point came in 2022.

It was a year of rising tensions between the US and China. The US was tightening tech sanctions. By early 2023 there would be talk of war. A major turning point towards escalation came in August 2022 when the then speaker of the House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, decided to end her tenure in office by making a statement visit to Taiwan. Beijing reacted with indignation and aggressive military maneuvers. Many in the region and beyond were glued to their screens, terrified that this might escalate towards war.

Acemoglu and Robinson took a more sanguine view. In the days following Pelosi’s visit, they took to the pages of Project Syndicate not only to warn against defeatism but to castigate those who were alarmed at the escalation as stooges of the CCP.

By accepting that authoritarian China inevitably will seize democratic Taiwan, too many Western commentators end up toeing the Communist Party's line. Rather than seeing Taiwan's future in present-day China, one can also imagine China's future looking like present-day Taiwan. Some Western commentators believe that Pelosi acted recklessly by visiting the island. But they ignore how and why Taiwan also matters for the future of both democracy and China itself.

Personally, at the time, I don’t remember worrying about Confucianism and its impact on Chinese political culture. But apparently that red-herring/straw man was what on the minds of Acemoglu and Robinson.

A common belief among Western policymakers and many commentators nowadays is that China will remain non-democratic for the foreseeable future, owing to its deeply authoritarian political culture. According to this view, the West’s “individualism” stands in stark contrast to China’s Confucian heritage, which entails rigid hierarchies not just in families but in all social settings. The implication is that the Chinese people are more willing to take their place within a pre-defined order of authority, and less willing to participate in democratic politics. While Confucius did say that “commoners do not debate matters of government,” he also emphasized that “a state cannot stand if it has lost the confidence of the people.” Confucian thought recommends respect and obedience to leaders only if they are virtuous. It thus follows that if a leader is not virtuous, he or she can – and perhaps should – be replaced. This perfectly valid interpretation of Confucian values underpins Taiwanese democracy. By contrast, CPC propaganda holds that Confucian values are utterly incompatible with democracy, and that there is no viable alternative to one-party rule. This is patently false. Democracy is as feasible in China as it is in Taiwan. No matter how strident the CPC’s bluster becomes, it will not extinguish people’s desire to participate in politics, complain about injustices, or replace leaders who misbehave. Taiwan matters because it represents an alternative political path for China – one that has long sustained freedom and prosperity in the West.

After reading those words you realize that the kind words from the Council of Economic Advisors undersell the association between the Biden administration’s agenda and AJR view of history. What are at stake here are not only freedom and prosperity, but injustice and ultimately nothing less than human desire. Regime changed advocated in the name of philosophical anthropology. As Cam remarked on the show, it makes one miss Frances Fukuyama and Kojève. Instead, the interpretation of modern history offered to us by this year’s Nobel prize winners in economics is an unreconstructed 21st-century Whiggery, fully in keeping with today’s neoconservative turn in America’s policy. It is Nobel sendoff for the Biden era.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. In an exciting new initiative we have launched a Chinese edition of Chartbook. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates. I keep them as low as substack allows, to ensure that supporting Chartbook costs no more than a single cup of Starbucks per month. If you can swing it, your support would be much appreciated.

Adam: something about Fukuyama which you likely know but which I didn't realize until recently is that he saw his enormous Political Order project not primarily as an attack on neoconservative ideas about exporting democracy. In FF's mind his main targets were North, Acemoglu and their co-authors. He wanted to offer a less economistic version of the same general narrative, one in line with his end-of-history anthropology.

(See https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/9780691217932-007/html and https://blogs.the-american-interest.com/2012/03/26/acemoglu-and-robinson-on-why-nations-fail/. There's also something to this effect in his book of interviews: https://press.georgetown.edu/Book/After-the-End-of-History).

Adam Tooze chat is like having a personal intelligence centre for the price of a good cup of coffee every day. Excellent!