Chartbook 327 From "anti-core" to "felt inflation": Or how I calmed my populist demons & resolved my cognitive dissonance on inflation, and how the Fed could do more to help.

Time to admit it: On inflation I’ve been suffering from cognitive dissonance. I’ve lived with my dirty secret for too long. Time to come clean. All the more so because thanks to Bloomberg columnist John Authers, I am much closer to resolution. What we all need to focus on, is what Authers calls “anti-core” inflation.

I was “team transitory” from start to finish. Cards on the table. I needed to be. I was all in on the giant fiscal stimulus in 2021. The evidence for supply-side shocks was strong. So much so, it seemed to me, that it was tendentious to even talk about inflation for much of the period 2021-2023. The price shocks were too sector-specific, notably in Europe. Intellectually speaking I am still fascinated by how aggregate macroeconomic phenomena like “inflation” get constructed. On that basis I don’t think that inflation is really the right word for what happened in 2021-2023. In the US, the price movement was undeniably more generalized, but there was no unhinging of inflation expectations and it never became a self-sustaining process. Price-hikes and profiteering had their moment, but the Fed hikes helped to slow the overall credit-fueled expansion and the unwinding of supply chain problems did the rest.

Overall, I feel pretty good about the calls that “team transitory” made during that period and confident that the fiscal and monetary mix since 2021 has been a great success.

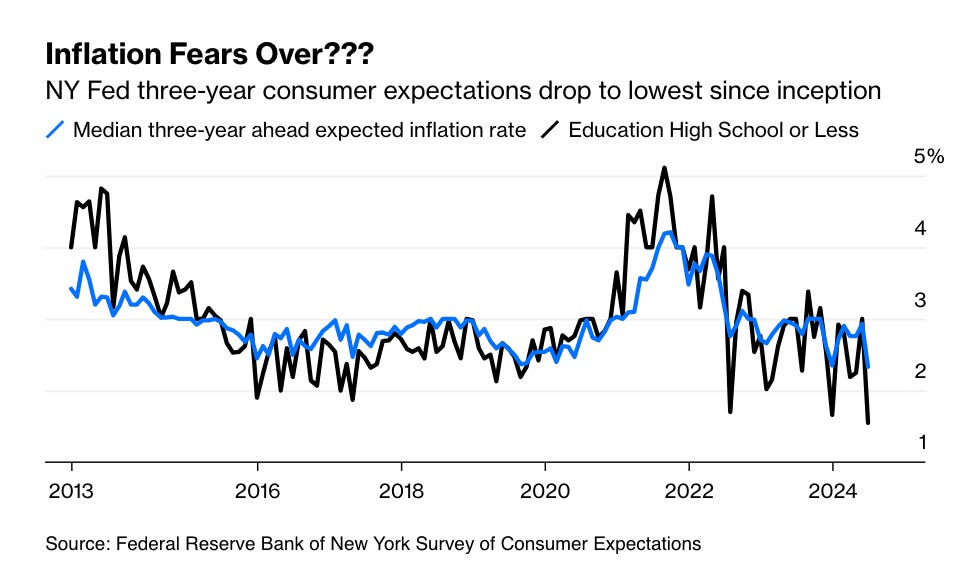

Now the inflation panic is well and truly over. Regular Americans, with few exceptions, have showed remarkable common sense about the future outlook. Amongst Americans with high school education or less, the three-year inflation outlook today is 2.5 percent. What more can you ask for?

Source: Bloomberg

So far so good, but this is also where my cognitive dissonance starts.

Because, yes, I actually do live in America and I have experienced what has happened on supermarket shelves. Several times I’ve been brought up short by jaw-dropping price hikes for everyday items - milk, fruit, veg, a cup of coffee, a loaf of bread, toothpaste etc. There’s been a price shock, all right. On the ground, in day to day life it feels far more serious than the data that dominate the macroeconomic policy discussion would suggest.

When pundits scratch their heads about why the American public is less enthused by the “state of the economy” than the macroeconomic data suggest they should be, I actually get it. If your budget is tight, it is not hard to understand why you are feeling pinched.

And yet the other half of me believes in the “goldilocks scenario” and the “soft landing” and knows that this recovery that we have been living through, is about as strong and fair as any that the United States economy and American society has experienced, ever, in recorded economic history.

So, what gives? I’ve been feeling torn. My inability to reconcile personal and macro narrative reached something of a crisis point in an Uber a few weeks ago, when discussing the economic situation with the highly sophisticated guy doing the driving. He had NPR on and they were reporting the inflation numbers. As we both guffawed with disbelief, I actually found myself saying: “Yeah, I don’t get it either. There is something wrong with the numbers. They aren’t capturing our reality, are they.”

I could feel the tug. Was I morphing from a sophisticated social constructivist on inflation, to being something closer to a “fakenews” guy? More seriously, what about the rest of the American public? What are citizens to make of such a jarring discrepancy between felt reality and the officially reported, technocratic version?

And then a few days back, I opened one of John Authers’ columns and found the answer: anti-core inflation.

As Authers explained it back in April on Bloomberg there really is a profound gap between the key measures of inflation which guide macroeconomic policy - headline and core inflation - and the prices that most of us use as our guide to “what things cost” in our everyday lives.

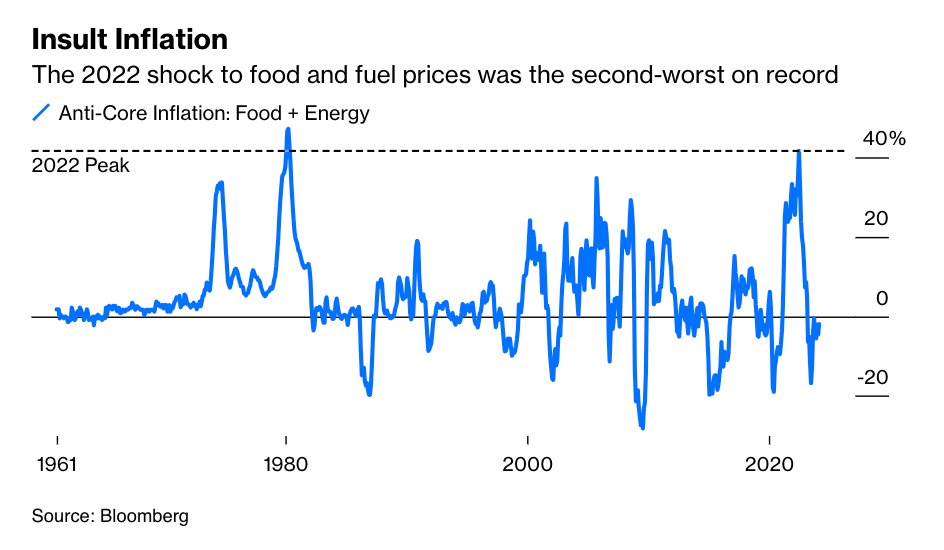

The crux of the issue for many consumers (explained to Authers by Jean Ergas of Tigress Financial Partners) isn’t headline or core inflation, but food and fuel. As these are exactly the categories excluded from the usual definition of the core, let’s call an index of combined food and fuel the “anti-core.” There’s a reason why central bankers find them useful to exclude, and it’s not because they don’t care; rather, food and fuel tend to be highly variable, and are in many ways beyond the reach of monetary policy. There’s also a reason why people outside central banks tend to care about them a lot. These are things that they have to buy, generally at least once a week, and any change hurts quickly. As Ergas puts it, inflation in these essentials is experienced by many as a further disenfranchisement, as adding insult to injury.

This seems spot on. The price increases for daily necessities have felt insulting.

As Authers continues, “The Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t regularly publish a measure for just food and energy. However, they have indexes for both categories stretching back to the late 1950s.” So, the Bloomberg team set to work and compiled their own anti-core index.

To do so, they focus on the bit of inflation that macroeconomics generally glosses over. Both food and energy have declined as a share of American budgets. But it seems fair to say that they still dominate our everyday perception of what things cost. If we combine them together on the basis not of their share in the overall index, but in terms of their weight relative to each other, this is what the latest release of the Authers anti-core index looks like.

Shazaam! Cognitive dissonance resolved:

If we focus only on food and energy, the price shock of 2021-2 was worse than that in 1973. It is second only to the Iran-crisis shock of 1979, the crisis that put paid to what little chance Jimmy Carter had of reelection in 1980.

Phew. No fake news. Just a familiar story of the way in which the construction of statistical series shapes our view of economic reality, both illuminating and obscuring.

I should have been reading Claudia Sahm more religiously, who highlighted the gap between Fed policy and food prices twelve months ago.

But now, cognitive dissonance is replaced by puzzlement, bordering on impatience and even indignation. I mean how on earth did the entire discussion not start here?

I understand, of course, why monetary policy has to direct itself towards the prices that can be seen as within the scope of macro policy.

As Matteo Luciani and Riccardo Trezzi report in an interesting note on core inflation numbers:

A consumer price index excluding food and energy was first reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) in the CPI Detailed Report for December 1975. Starting in 1978, this exclusion index was routinely included in the CPI Detailed Report; subsequently, a similar exclusion measure was computed for the price index for personal consumption expenditures in the national accounts. The rationale behind an exclusion index is quite simple, and involves excluding a fixed list of items that are judged to be relatively more volatile and more subject to idiosyncratic shocks on average.3 Indeed, when it was first introduced, this index was not motivated in terms of the estimated statistical properties of food and energy prices; rather, its use reflected the 1970s' experience of high commodity price volatility and represented an attempt to reduce the variance of measured consumer price inflation while maintaining its average over longer periods.

The intellectual rationale for core inflation numbers is clear enough. And macroeconomics is all very well. But policy has a political context and public perception matters. It should interest all policy makers including economic policy makers, particularly in a democracy. So something like the anti-core index should also feature on their dashboard. What is more, the public ought to be able to look over the Fed’s shoulder and watch that dial.

Looking back at this personal episode, I realize that a far more general point is at stake here. If folks like me, who follow economic reality in a nearly obsessive way, cannot reconcile personal experience with “data-reality”. If someone like myself listens to NPR in the back of a cab and feels the populist demons tugging at me and begins to wonder about whether it is all “fakenews”, it is kinda funny, but it also raises a more serious point. What are the vast majority of folks to make of the situation, who don’t take a professional interest? How are they to process the jarring discrepancy? Are we not positively inviting disillusionment and cynicism. How can they not believe that policy elites are either out to mislead them, or are themselves out of touch?

So here is the suggestion. The Fed and other responsible agencies should face this problem head on. They should either adopt anti-core as an official indicator, or they should introduce a new measure akin to weather forecasting which differentiates between thermometer inflation and “felt inflation”.

The message should be this: “Hi citizens, as monetary policy makers, we think you will agree that it makes most sense for us to focus our interest policy on the prevailing trends in the economy. That is why we are focusing on core inflation. That excludes a bunch of highly volatile stuff. If you think of the Fed as being at the wheel of the nation’s economic school bus, you wouldn’t want us yanking the steering wheel around in response to every bump in the road. But we know those bumps are real and you are feeling them. We are not in denial. We buy groceries too. So we know that “felt inflation” right now diverges from what we are targeting. Our best guess concerning “felt inflation” or something we call anti-core is x percent. That hurts. Our policy should, in due course (long and variable lags), translate into the end of big price hikes. But it will take time and people are going to hurt. So, if you feel we should do something about the bumps, we collectively - not us the Fed, remember we are driving the school bus not managing roadworks - should be discussing how to fix the road and to ensure that those who are worst hit don’t suffer acute hardship. But, believe us, we are not in some alternate reality. We are in the soup with you, trying to make sense of this confusing situation as best we can.”

That, it seems to me, would be a better message for democratic economic policy to be delivering than simply: “Everything is under control. Trust us. Despite what youa re feeling, this is a good economy.”

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. In an exciting new initiative we have launched a Chinese edition of Chartbook. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates. I keep them as low as substack allows, to ensure that supporting Chartbook costs no more than a single cup of Starbucks per month. If you can swing it, your support would be much appreciated.

So the explanation here seems to be that central bank creates and reports a measure, the core inflation rate, based on whether it can manipulate that rate through it's available monetary tools, then claims victory when that core inflation rate is manipulated in the way it expects. Where is the extrinsic value of this measure here? If this inflation rate does not actually impact food and fuel and rent, the things that literally everyone else cares about. This seems recursive - the bank is setting its own goalposts only on what it can actually achieve then patting itself on the back for achieving the goal.

It has never made sense to me that they leave out food and fuel. That they left it out because those elements are volatile makes me think of the fact that scientists traditionally left women out of medical trials because it was too hard to calculate the variables. Garbage in, garbage out. Separately, what I find missing from such discussions is that businesses put less of that money toward worker salaries (corporate profits at all time highs, stock buybacks, etc., instead of wages). Maybe the higher price of eggs wouldn't pinch so much if the wages matched.