Chartbook 323: Three theories of "swing states". Or the puzzle of why and how 150,000 American voters will decide all our futures.

America is a country of 330 million people and 161 million registered voters. Its policy affects the entire planet of 8 billion people, whether it be through foreign policy, trade, climate policy or tech. Its elections cost billions and are followed around the world. The USA likes to boast that it is the “world’s greatest” democracy. That claim implies that majorities matter i.e. the great mass of the population of 160 million voters decide who governs. And yet in the view of America’s leading political experts, that is far from being the case. As one of them put it to National Public Radio:

“For me, this presidential campaign is coming down to maybe 150,000 voters that are decisive,” Schultz said.

How can this be?

If we imagine the US as one giant constituency of 160 million voters and arrayed all the voters from right to left along an ideological spectrum one can imagine a hotly contested election in which the country split, 80,000,001 voters v. 79,999,999. In that case you might say that the struggle came down to a handful of undecided voters in the middle of the ideological spectrum who ultimately picked the winner.

If that were the case, it would be no scandal. On the contrary it would be the logic of democracy in action. But that is not the kind of political contest that is going on in the USA today. The “scandal” of the US election is not that it is a titanic struggle for tens of millions of votes that will ultimately be decided by a fine margin. The scandal is that tens of millions of votes barely attract any attention at all. Only a few places matter and those places are determined by no obvious, larger-scale logic. Furthermore, their votes are often influenced by highly idiosyncratic local conditions. It is a few thousand voters, often in out of the way, “backwater” places, that decide the future of the USA and with it, the future of the world.

How can this be?

The starting point is that the basic structure of the US political system is still defined by a constitution drafted in the late 18th century. The patchwork of states is defined by the legacy of US territorial expansion in its imperial phase in the 19th century, when it was aggressively incorporating most of the continent of North America. This has shaped a sprawling federal polity made up of very unevenly sized states. Those states send delegations to the electoral college, which actually elects the President, a device not uncommon in early constitutions. The composition of those state delegations is decided in the vast majority of cases on the basis of simple majorities, again a crude electoral mechanism shared with the United Kingdom, another “ancient constitution”. Whichever party has the largest number of votes in a state gets the delegates.

This, by itself, does not necessarily create the pattern we see today. If states were similar in their political make-up, all states would be swing states. The 18th century constitution provides the frame, but what creates the weird shape of US democracy today are further processes of differentiation, polarization and sorting, as Americans have increasingly migrated and congregated into communities that are relatively more uniform in political terms than the nation viewed as a whole. That tendency has been reinforced as politics have become more polarized and have begun to color more and more areas of life, meaning that we can now meaningfully talk of “red” and “blue” states with different politics corresponding to very different modes of life. On a question like abortion rights it is no exaggeration to talk of the USA as one country with two systems.

Put all these factors together and it means that in most parts of the USA the local outcome of the US Presidential election is a foregone conclusion. New York state, regardless of what happens in its many rural areas, will go for the Democratic party candidate. Push this logic to its final conclusion and one could imagine a situation in which the entire election was a foregone conclusion. The dirty secret of democracy - like that of capitalism - is that for all the celebration of competition and choice, in fact, the players in the system all dream of the day in which competition will cease and they will command a legal monopoly. Their nightmare is the opposite, that the other side establishes that lock-grip.

US politics today are fired by that fear - that the other side will establish a monopoly. But the actually existing state of affairs is very hard to call because the states that are solidly in both camps are not enough to give either side a clear majority.

That means that the final outcome is decided by a handful of battleground or swing states. Many states in the US have small electorates of a few million or so. And then, at the state level, the same logic repeats with sorting and the formation of solid Blue or Red constituencies, in big cities and small towns and rural areas, which means that in the end the entire election comes down, not tens of millions or millions, but a few hundred thousand voters in “battleground counties” dotted around the country. If the true number is 150,000 decisive voters, that is one tenth of one percent of the entire electorate.

The common language for these key locations is battleground or swing states/counties. If we wish to impose a sharp distinction on fuzzy political language, battleground states are places where the election is close. Swing states are states where the electoral result has swung from one party to the other, whether the margin of victory is large or small. In psychological terms you might say that whereas battleground states are undecided, swing states are characterized by mood swings.

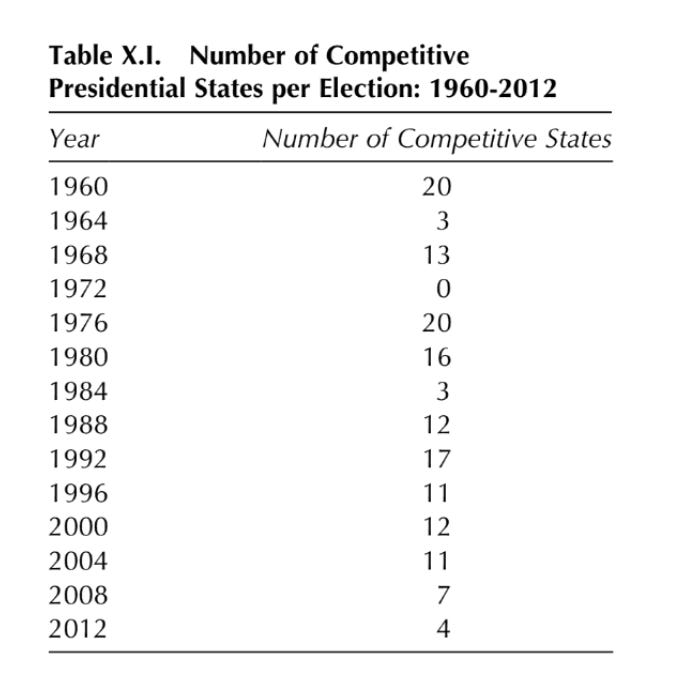

Since the 19th century it has been true that particular battleground states have been vital to the outcome of US Presidential elections. There has always been a focus on close races. The term “swing state”, by contrast, only came into widespread in the early 2000s, as America began to worry about polarization and sorting, and the phenomenon of switching sides became more and more unusual. Taken together the currency of both terms indexes the declining number of states where the outcome is not predictable in advance. By 2012, according to one enumeration, we were already down to 4 states.

In 2024 there are reckoned to be seven key states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

Taken together the swing states are a significant group of voters and a considerable economic power. As one report puts it: “For perspective, those seven states form a battleground economy with a population of 61 million people and a combined gross domestic product worth $4.4 trillion—a figure that rivals Germany’s output.”

But look more closely and you realize that a. they do not actually form a coherent whole and b. even with those states the election will be decided by far smaller and more concentrated groups of voters. American political science digs deep. So we also have enumerations of more and less hotly contested counties. Once again, due to sorting and sifting the number of these has been declining. Of course one should beware assuming that hotly contested counties are mainly in hotly-contested states. That may not follow at all. You can have hotly contested counties in states that are otherwise solidly red or blue. Those counties are worth watching because they may allow us to infer voter behavior elsewhere, even if in the state in question the influence on the final outcome is minimal.

Clearly, the counties that matter most are the battleground or swing counties (sometimes called pendulum) in the states that are actually “in play”. This is why you find a political scientists like Schultz telling NPR:

Even within swing states, not every voter is a swing voter. Schultz suggests that this year’s presidential contest could hinge not simply on swing states but swing counties. He estimates that 5% of the voters in five counties in five states could determine the outcome of this year’s contest. “For me, this presidential campaign is coming down to maybe 150,000 voters that are decisive,” Schultz said.

So the next obvious question is what actually makes a swing state a swing state? Why is the election in these parts of the USA so close and the outcome seemingly underdetermined?

As far as I can see there are three distinct interpretations.

One is that voters in swing states are different. Whereas voters in most states can be neatly sorted into red or blue, in swing states there are more purples. This might be explained by a distinct cultural influence e.g. the Mormon religion, which shapes a particular coloration of conservatism different from that in New Jersey or Mississippi.

Theory two is that the voters in swing states are just as clearly differentiated into red and blue as in other states, but they are thrown together by historical accident within the boundaries of a single state in such a way as to make for a fine balance. You might call this a theory of incomplete sorting. Perhaps they will eventually sort into one camp or the other. Or perhaps the sorting will remain deadlocked.

A third interpretation focuses less on the voters and more on the places. Lets call this the “states of change” theory. It sees swing states as places to which or in which things happen - structural economic changes for instance - that either divide the electorate in ways that make the outcome hard to call, making them battlegrounds, or shifts the electorate first one way and then the other, making them swing states.

These three logics of regional electoral competition in the USA are not mutually exclusive. They often overlap. Nor are they static. Ideologies and attitudes shift. Out of structural changes emerge new structures which then ossify. The self-sifting and sorting of the American population is continuous. Florida, to take one example, was once a key battleground state. It is now rarely mentioned because it is taken to be solidly Republican and the radicalism of the policies of Governor DeSantis may cause further sorting in that direction.

But even if they shade into each other, these three logics are distinct and for the by-stander and reader of political coverage of the election it is clarifying to see how they are invoked to explain the contests that really matter in the US election.

Before I go any further, I should add that I am writing this as much as anything as an exercise in self-help. Cam and I decided to discuss swing states on the pod and I realized that though anyone can list the seven states in question this year, I did not really know or understand why they were the way they were and what made them special.

I did the obvious thing. I trawled google scholar looking for academic political science on “swing states” and “battleground states”. The best I could find was an edited collection from 2015 on Presidential Swing-States, which claims that there was, at least at that point, little or no serious attention paid by political scientists to the topic. In other words, the idea of “swing states” and “battleground states” are folks concepts native to the political commentariat. There is a vast amount of highly sophisticated statistical work out there on electoral behavior. But when I looked for a general explanation of the phenomenon of the “swing state” I came up empty. In proposing my “three schools of thought”, I am engaged in a first-principles, back of the envelope exercise. I am more than happy to be schooled by those who know better.

For an example of theory #1, purple state commentary look no further than Rana Foroohar in the Financial Times. Under the headline: “What Swing States Want”, she writes:

States including Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are some of the most politically heterodox in the country — that’s why, of course, they are swing states. I was struck by some recent polling done by Blueprint, a left-leaning public opinion research initiative, that speaks to this point. As they put it, “swing state voters are ideologically eclectic: They hold conservative views on immigration and crime, but are pro-choice and favour government action to control corporate excesses, particularly on prices. They reward pragmatic populist positions rather than strict ideological consistency.” They also “favour politics that punish corporate bad actors but are sceptical of government over-reach and sweeping systemic change rhetoric”.

This essentializing analysis of “the swing-state voter” leads Foroohar to conclude that Kamala Harris may be onto something in her vague gesturing towards actions on price gouging and coming down hard on corporate malfeasance. “Swing state voters”, Foroohar, suggest like smaller deficits, less red-tape and tighter immigration control. “Sixty-nine per cent of swing state voters believe in deficit reduction, though they also seem to be tolerant of more government intervention in markets (only 23 per cent agree that “Soviet-style price controls will only make inflation worse”.)” From all of this Foroohar derives the conclusion that

Harris’s somewhat vague, yet pragmatic approach on the economic front isn’t such a bad thing. She needs to capture people with a lot of differing viewpoints right now, and while more joined-up systems thinking will be necessary for making good policy should she win, heterodoxy might serve her well now.

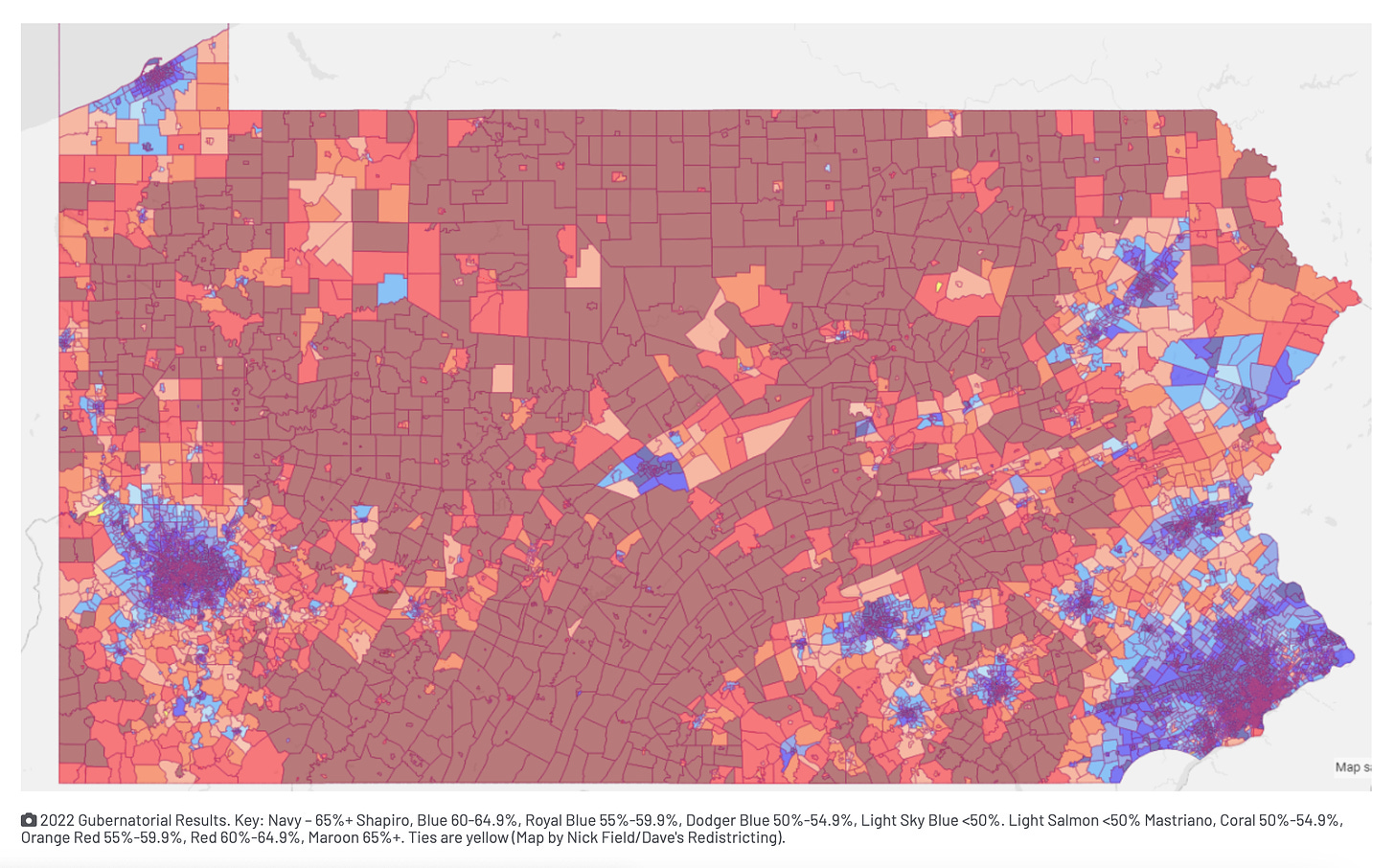

A rather different kind of analysis comes into play if we look closely at a key state like Pennsylvania. The map in that state is not purple so much as starkly polarized between a sea of Republican Red in the rural areas, and tightly concentrated patches of Democratic votes in and around the major cities.

This is the map of Democratic Governor Josh Shapiro’s landslide victory in the statewide Pennsylvania election of 2022.

His win was based on a solid base of voters in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and Harrisburg combined with strong appeals to the immediate suburbs which have been swinging hard towards to the Democrats since 2018. The question for the Democrats is not so much how to dilute their message so as to appeal to Republican areas, as to force up their vote in those territories that are already on their side.

Go into the more rural areas of Pennsylvania dotted with small towns and you find Lancaster county. As local experts comment:

Lancaster is historically one of the strongest Republican counties in the commonwealth: the list of post-war Democrats who’ve won Lancaster is incredibly small, confined to the landslide victories of President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964 and Gov. Bob Casey Sr. in 1990. Shapiro fell just 3,807 votes short of joining that list, performing extraordinarily well in an area where Democrats continue to be on an upward trend. As for the impetus behind this shift, I’ve theorized that perhaps Donald Trump-branded MAGA politics are a poor match for the local Amish community.

To further anatomize these fine, local balances, analysts often shift to the “states of change” perspective. This asks how ongoing social, economic and cultural changes differentially impact across the United States to create local political ecologies.

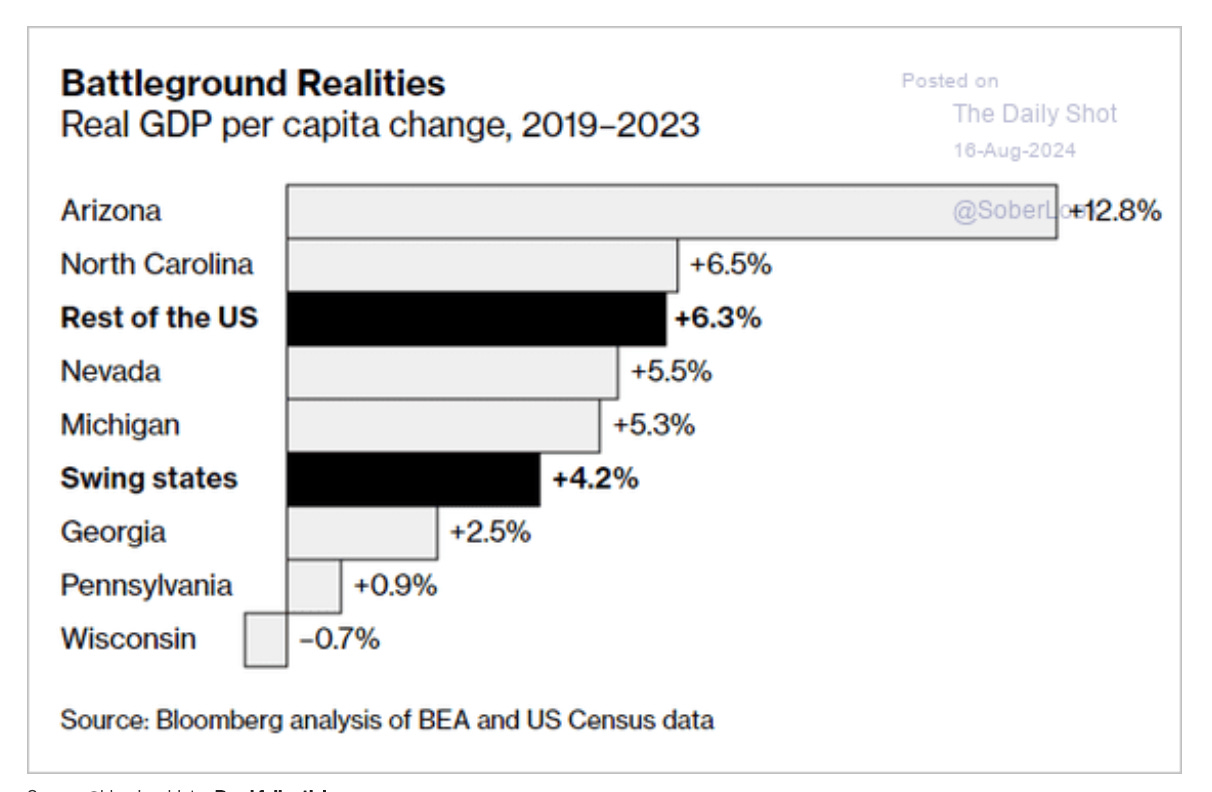

If you take real per capita economic growth over the most recent cycle, there does not seem to be anything that unifies the swing states. For sure, since 2019 five of them have seen growth somewhat below the national average. But Arizona has experienced a veritable boom, where Pennsylvania and Wisconsin have struggled. Rather than a common “swing state experience”, it is more the differences that meet the eye and those in turn reflect variation that we would expect to see across the regions of a huge country like the United States.

This leads some analysts to despair of finding any clear cut economic trends that would help us decipher the likely outcome in the swing states. They conclude that the swing states are pretty average in economic terms and so it will be non-economic factors such as personality or the culture wars, that will decide the issue.

Presidential candidates Kamala Harris and Donald J. Trump are both keenly focused on economic conditions in seven American swing states. But swing-state economics might not matter this year. That’s because job growth, inflation, wage gains, and other economic factors in those seven states—Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—roughly mirror national trends. That could make their economies less influential in deciding the Nov. 5 election. “The swing states are sort of in the middle on almost every measure,” says Julia Pollak, chief economist for ZipRecruiter. “They are somewhere between the red and the blue because their policies are more of a mix.”

Unemployment in the swing states is generally below the average. State-level inflation varies around the national average. And consumer-sentiment is likewise hard to distinguish from the national trends. These however are statewide assessments - talking about Pennsylvania as a whole, or Georgia - and if recent years have taught us anything, it is the need to focus on local circumstances down to the county level.

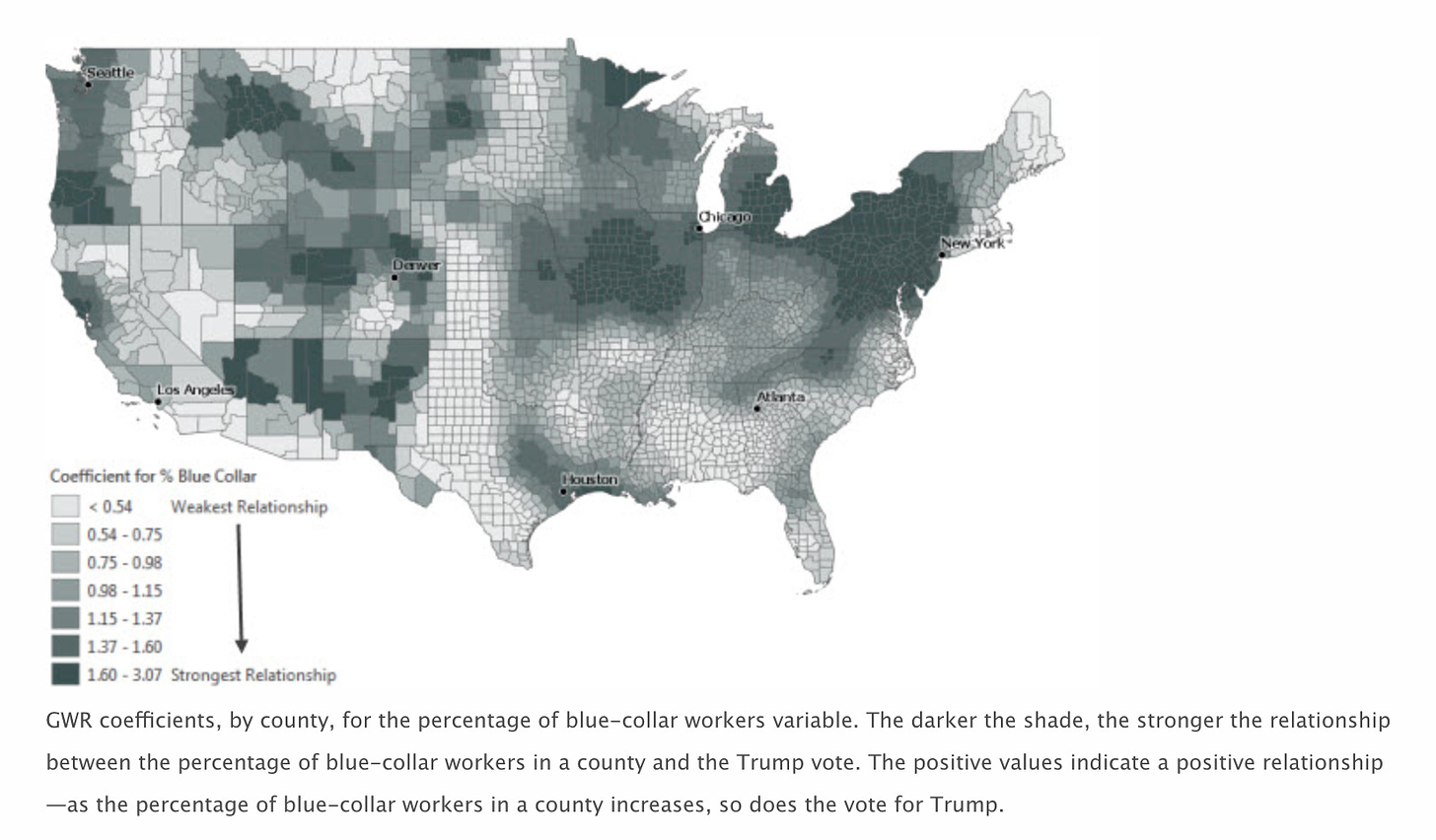

In 2016, Donald Trump’s breakthrough election, it was widely remarked that working-class, blue collar voters, haunted by fears of deindustrialization, globalization and the “China shock” defected from the Democrats led by Hillary Clinton to Donald Trump. That finding shaped an entire theory of economic politics in the Biden camp. It will be tested again in the upcoming election. Less remarked upon at the time and since, is that it was not only the case that working-class votes tended to go for Trump in 2016. The situation was even more damaging for Clinton and the Democrats because in the rustbelt states working-class voters were even more likely to go for Trump than they were at the national level. In other words, in the regional political context, his message hit home especially hard. Local class antagonism or concentrated campaigning may have created this effect.

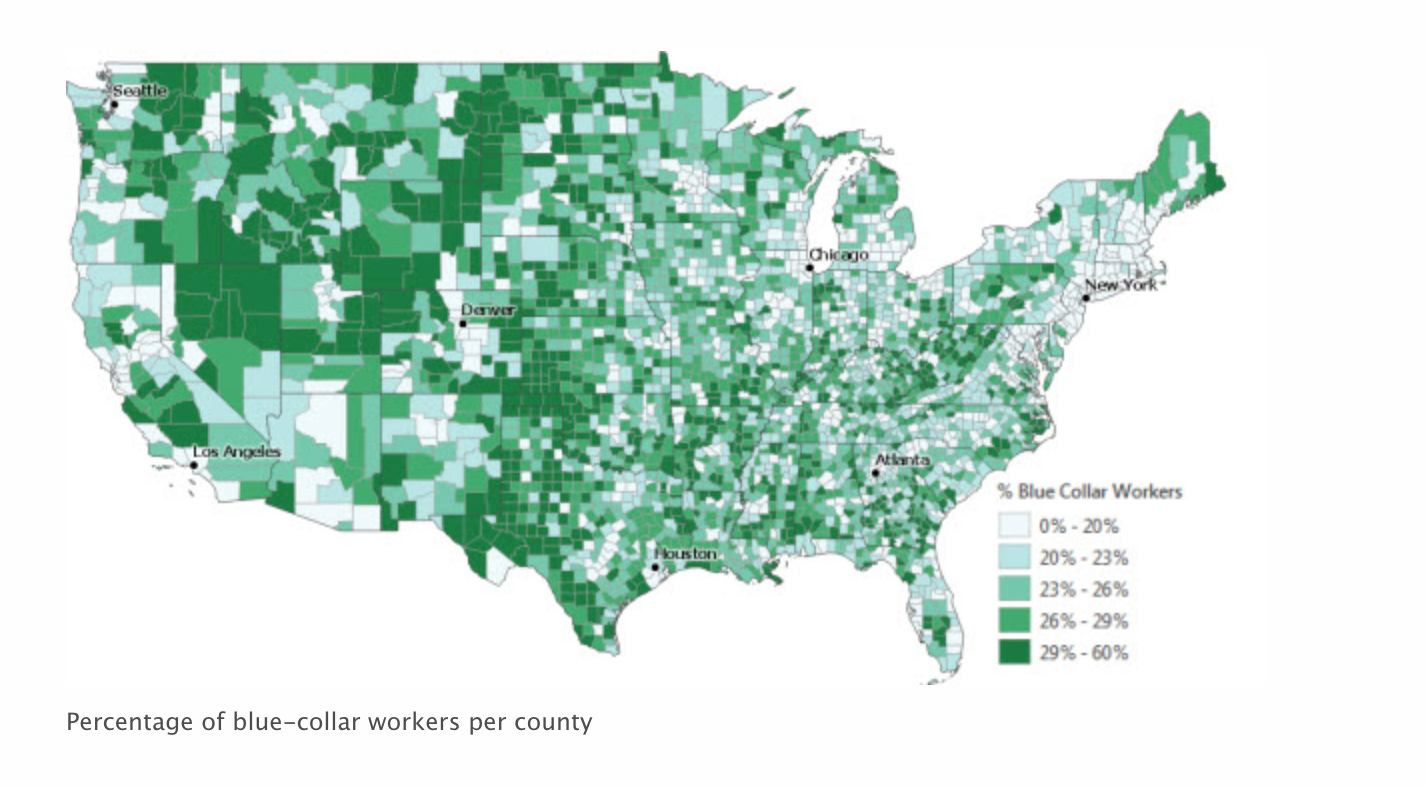

Source: ARCGIS

Not all counties with this high propensity of working-class voters to support Trump actually had large working-class constituencies. But in key counties in central Pennsylvania and West Virginia those two factors did come together. Not only did they have outsized correlations between blue-collar voters and Trump voting. They also had outsized shares of blue-collar voters.

It is the compounding and combination of such effects that creates distinctive regional patterns. And it is this which caused the Biden team to focus not just on industrial policy in general but on “place-based” strategies to help “lagging communities in the name of what’s been dubbed a “modern supply side economics” and “liberalism that builds.”:

Entire teams of Bloomberg reporters led amongst others by Shawn Donnan, Alexandre Tanzi and Elena Mejía, have been traveling the swing states in the hope of uncovering these local place-based dynamics that may well decide the election. As one report notes:

When you dive down to the county level, you find a disproportionate share of the population across swing states is living in counties that, based on the latest available data, had not recovered to their pre-pandemic real GDP per capita by the end of 2022. In Pennsylvania, 40% of the population lives in a county that fits that description. Across the US, the equivalent figure is closer to 20%. Even in faster-growing sunbelt swing states, the picture is complicated. Arizona has enjoyed strong real GDP per capita growth thanks to big investments in new semiconductor plants and population growth. But inflation and soaring housing costs have hit household budgets hard, much as they have in Nevada and North Carolina. Few states have benefited more than Georgia from a boom in electric-vehicle and battery plants under Biden, but it’s also seen its growth diluted by a swell of new residents.

Bidenomics promised to deliver new industrial jobs, but in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin, the so-called Blue Wall States, there are “fewer people working in factories than at their pre-pandemic peaks in 2019”. And the cost of living is hurting. As one North Carolina based entrepreneur remarked: “People don’t put GDP in their gas tank. They don’t buy GDP at the grocery store. And that’s where most of the angst is in the economy,” Vitner said. “Someone who is working in an EV plant in Greensboro, North Carolina, is just as frustrated with higher gas prices than if they were working in a furniture factory.”

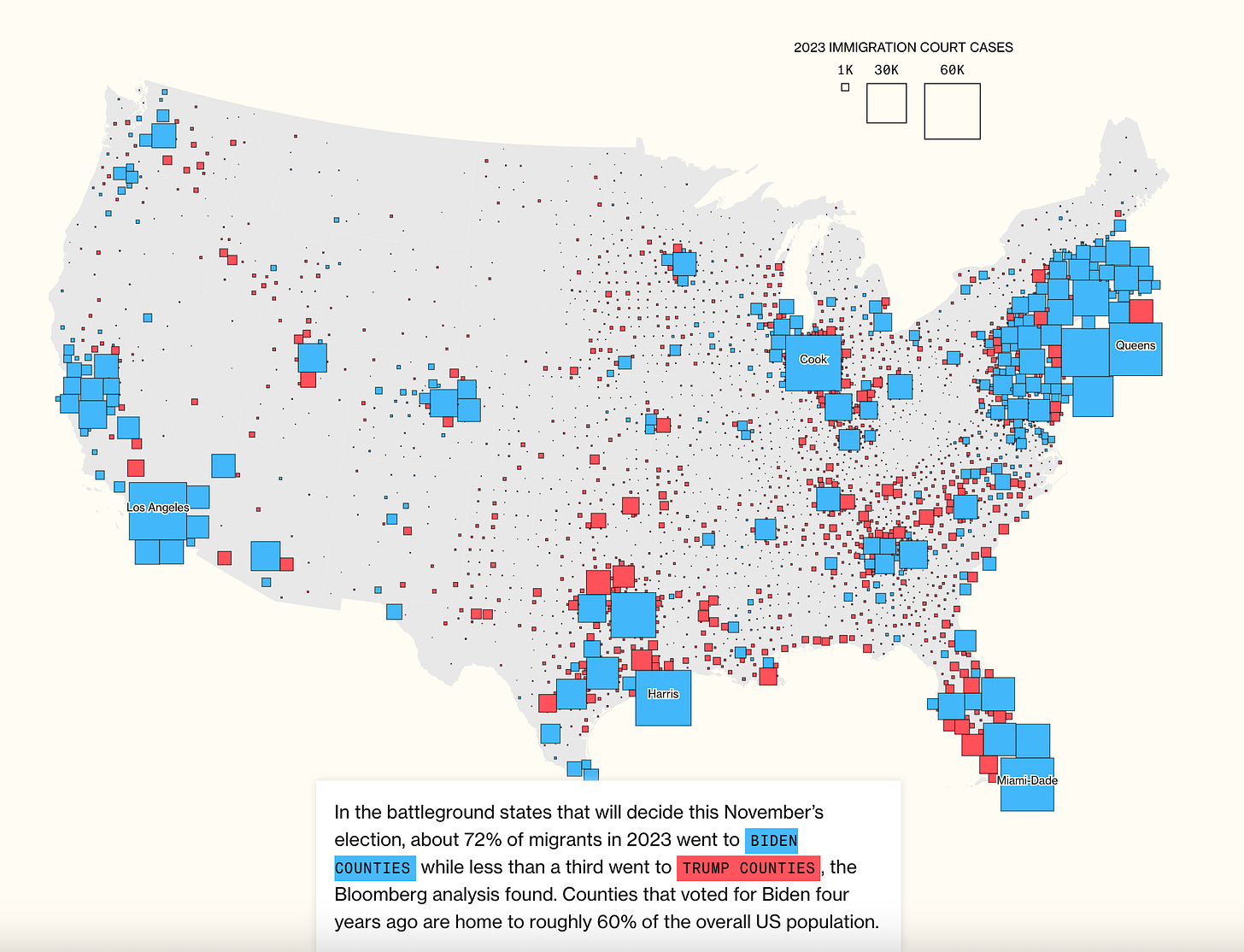

National talking points like migration are local in their impact, as was shockingly illustrated by the singling out of Springfield Ohio. Haitian migrants were attracted to that community because it was growing fast. And this is the national trend.

Migrants are attracted by growing communities, which tend to vote Democrat. Their presence scandalizes xenophobic and racist voters, appealed to by Republicans, voters who themselves tend to live in slow-growing or even declining communities, whose relative depression is reinforced by the lack of in-migration. And political advertising preys on this vicious circle. As Bloomberg reports:

As of last month, Republicans had spent over $150 million this year to fund immigration-focused ads that air in swing-state TV markets … Almost two-thirds of that money comes from the Trump campaign and two Trump-supporting super PACs .. And those groups have spent more money on immigration-focused ads than on any other issue, with almost half their spending in swing states going to Pennsylvania and Georgia. In Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, for example, 73% of their total spending went to ads with an immigration focus. One says “Pennsylvania is paying the price” after Biden “let all these people in.”

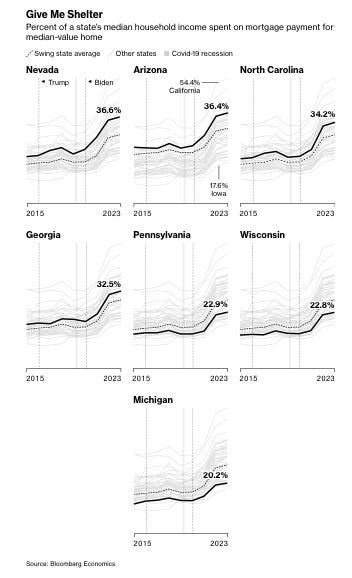

Apart from racism, the economic logic behind the anti-immigrant propaganda is to do with housing. The claim is that inward migration drives up housing costs. And this bites on a powerful reality in the swing states. As the Bloomberg team comments:

While Joe Biden had manufacturing and blue-collar jobs at the center of his economic agenda, Harris has centered hers on bringing down household costs and increasing access to homeownership.

This reflects the reality of swing state concerns:

Accepted wisdom used to be that the key to voters’ hearts and minds in these areas lay in promising to bring back manufacturing. … Today, however, housing affordability is likely to resonate more powerfully. Bloomberg Economics calculations show that in the sunbelt states of Arizona, Georgia, Nevada and North Carolina, the cost of mortgage payments on a median home has roughly doubled since 2016, to a third or more of median income. In the industrial states of Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, median households pay roughly a fifth of their income for mortgages on middle-of-the-road homes. Their costs have also doubled since 2016.

Does this kind of analysis do away with the anomaly that a comparatively tiny number of people will determine the outcome of an election that shapes the world? No it does not. Does micro-analysis like this suggest that voters in those key constituencies are moved by great global concerns, which may ultimately be decided by the incumbent in the White House? Certainly not. Democracy does not promise or deliver that. What it does deliver is a political process that at least at this moment, with weeks to go to the election, is intensely focused on messaging to a select group of “ordinary Americans” about what research, local expertise and best-guesses suggest are their most pressing day to day concerns. Everything is driven by seemingly simple but actually mysterious questions: What matters to these people? What will cause them to vote one way rather than another? One might wish for more debate. One wants to argue with people and persuade them with reasons. But that is not how this game is played. The question is which discursive button to press. As we await the outcome on November 5th (and the days that follow) we are all forced to care because so much hangs on it. It is not up-lifting. In many cases it is downright ugly. But beyond the high-flown language of the constitution and the legal niceties of rights and voting procedures, it is this question, in all its intensity and open-endedness and all its arbitrariness that defines actually existing democracy.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates.

Here's another way to think about it: it's a product of the nationalization of US politics. Each state's average swing in two-party vote share between elections used to be much higher and there used to be less correlation between states, because politics was more local. Hence the idea of a "swing state" was unnecessary because consequential swings could happen in nearly all states. Now US politics is both more national and more calcified, and the "swing states" that are left are the ones in which changes can still plausibly matter to the outcome.

I would like to add a comment on the electoral college from a completely different perspective, that of national security. I would be hard pressed to find a system increasingly more vulnerable to the evil machinations of foreign and domestic actors than the Electoral College system and the unique concept of swing states. It is ridiculously easy and cheap for these folks to focus exclusively on the swing states whereas a popular vote for the president would require vast resources of time and money to enable tampering with the election.

Interestingly, all statewide offices (governor, senators, attorneys general) are run as popular votes and nobody complains about them except where there is voter suppression.