If there is predictable rhetorical flourish to accompany visions of American power, more often than not it is a reference to the Marshall Plan. Announced in the early summer of 1947, the Marshall Plan propelled the first concerted effort to coordinate and integrate West European reconstruction after World War II. The plan was big. Over the lifetime of the plan into the early 1950s, US spending came to around $13 billion, all told. Adjusted for inflation that would be $200 billion in today’s money. Scaled to GDP, a better measure of economic effort, the Marshall Plan is even more impressive. By the end of the program, the Marshall Plan came to roughly 5 percent of 1947 US GDP. A proportional effort today would exceed a trillion dollars. It would need to be even bigger if we allow for the fact that in the 1940s large parts of the USA were still, by modern standards, underdeveloped, lacking basic amenities like electrification or indoor toilets. At least notionally, our affluence today should free up a far larger “surplus”, making a 5 percent effort more manageable than in 1947.

The Marshall Plan was a unilateral act of far-sighted leadership by the USA. It was a characteristic product of New Deal thinking in the wake of the mobilization effort of World War II. It is widely credited with having launched postwar Western Europe on the road to an economic miracle. Not surprisingly, it has to come to be seen ever since as the ideal type of grand geoeconomic policy.

I will have more to say about the Marshall Plan as a historical event in future notes. What concerns me here are its echoes in policy discourse today.

If anything, the mystique of the Marshall Plan is even stronger amongst America’s allies than in the United States itself. As Alan Beattie archly points out in the FT,

Gordon Brown, the former UK prime minister, (has) called for at least five Marshall Plans within 15 years, respectively for aid in general (2001), aid specifically for Africa (2005), combating climate change (2007), expanding global financial regulation (2010) and, perhaps overstretching the concept a little, helping Syrian refugees (2016).

It should, therefore, come as no surprise in an American election season, to see Brian Deese - Director of the White House National Economic Council from 2021 to 2023 - calling for a Clean Energy Marshall Plan in the pages of Foreign Affairs.

As Deese himself notes, talk of a Marshall Plan is a cliché that is likely to induce eye rolling.

But the risk, in this case, is not so much that we roll our eyes, as that, out of habit and repetition, we pass over Deese’s appeal without noting just how symptomatic it is of the impasse that American grand strategy finds itself in today.

Since 2021 claims to leadership on a variety of global issues have come thick and fast from Deese and his colleagues around the Biden administration. One thing we have learned over recent years is just how readily American liberals still resort to talk of American global leadership. At least publicly, the Biden team devoutly believe that big global problems have American solutions.

And it is undeniable that there are domains of policy in which claims to American leadership are little more than a tautology.

If the dollar-based global financial system suffers a near-fatal heart attack - as in 2008 and 2020 – only Fed intervention can help.

If one of America’s associates or allies is drawn into a war or proxy conflict, then it is hardly surprising that it is America’s over-inflated military machine that comes into play. The Pentagon doesn’t have the budget that it does for the purpose simply of deterring threats to the continental United States. That could be done at a fraction of the cost. Global military powers do global military power.

Recently, the significant exception to that rule was the withdrawal from Afghanistan, a personal priority of Biden that turned into a debacle both on the ground and in terms of public opinion in the US.

At the current moment, dollars and bombs (in the extended sense), are the visible sinews of American power. In the background, there is data, intelligence and big tech. America also has a big lead in many areas of space technology.

All four dimensions - finance, bombs, data, space - really matter. But as a hegemonic project they are thread-bear. Much of the time the US does not even bother to offer complex legitimations for their deployment. The US deploys its power in defense of what Washington defines as the national interest, including the interests of foreign or commercial lobbies that are willingly granted outsized influence over decision-making, or allies, notably Israel, to which the US effectively delegates decision-making authority.

When, however, the Biden administration has attempted to formulate a project of power in more capacious terms, for instance around the idea of “democracy v. autocracy” or in defense of the “rules-based order”, it falls flat and lacks credibility.

The parlous state of American democracy is no secret. America’s flouting of the fragile institutions of international law and order is obvious for all to see and makes any reference to a “rules-based order” seem hopelessly hypocritical.

And, yet the high-flown claims to leadership keep on coming and the high-point of US hegemony in the 1940s continues to be invoked. The result is a notable scrambling of politics and history. The Deese proposal for the United States to launch a Clean Energy Marshall Plan is a particularly egregious case in point.

In the name of the Marshall Plan, Deese proposes that Washington should claims leadership in a field – the industries of the clean energy transition – in which the US is demonstrably is not a leader, but lags far behind its main geopolitical rival. Deese does so, not simply by invoking the Marshall Plan, but by rewriting the Marshall Plan’s history so as to reduces it to a crude extension of US export-promotion and industrial policy. The tension between the fabled past and the thread-bare state of American power in the 2020s is, thus, resolved by flattening the history into the shrunken frame of the present.

The Marshall Plan was based on a vision of postwar European reconstruction, centered on promoting industrial and infrastructure investment and European integration, including the reintegration of Germany. That this would ultimately benefit America and the American economy was obvious. But only the crudest materialist interpretation of the Marshall Plan would reduce it to a glorified export promotion scheme. And yet that is exactly what Deese insists on. The Marshall Plan is so relevant to the US today, Deese asserts, not because of its high ideals, or its capacious vision, but because it offers a model of industrial export promotion gone right.

Here is his rendition:

Fundamentally, the Marshall Plan was an industrial strategy that deployed public dollars to advance U.S. manufacturing and industrial capabilities in service of reconstructing Europe. Washington spent $13 billion—equivalent to $200 billion today—over four years, mostly in the form of grants to discount the European purchase of goods and services. Because U.S. companies were at the center of the program, 70 percent of European expenditures of Marshall Plan funds were used to buy products made in the United States. Italy, for example, used Marshall Plan funds to buy American drilling technology, pipes, and other industrial equipment to rebuild its energy sector—including the equipment needed to restart Europe’s first commercial geothermal plant, powered by steam from lava beds in Tuscany. By 1950, that region had more than doubled its geothermal capacity and remained a major contributor to Italy’s total power demand.

In fact, the most urgent problem in 1947 was not the promotion of American industrial exports, but the “dollar shortage”. In their damaged postwar state, traumatized by the experience of war and crisis in the 1930s, European economies were locked in a system of tight exchange controls that overvalued their exchange rates relative to the dollar, encouraging imports and rendering exports uncompetitive. To manage the resulting dollar shortage, European countries resorted to rationing imports and became dependent on a series of bilateral aid and loan deals with the United States. By the spring of 1947 with the Cold War escalating, it became clear that this risked an escalating downward spiral, in which occupied Germany and France, where the Communist party was surging, might well become dangerous flashpoints. The aim of the Marshall Plan was to break this gridlock without imposing traumatic deflation as had happened after World War I. Rather than imposing immediate devaluation and austerity, the Marshall Plan provided dollars for imports and investment, not on the bilateral hub-and-spokes model that had prevailed since 1945, but on the basis of a common program of European recovery.

It hardly needs emphasizing that today the chief problem of the world economy is not a “dollar shortage”. Despite painful bouts of dollar strength, thanks to America’s deficits and generous credit policy, the world is awash with dollars.

If one were looking for a true Marshall Plan analogue in the current moment it is to be found in China not in the USA. China unlike the USA and like the economies in the 1940s operates exchange controls and is running a huge trade surplus. In the summer of 2024 there were calls from both inside and outside China, for a scheme that would provide financing for the export of Chinese new wave of manufactured goods. With funding provided, Chinese exports would entail a build up debt and would displace local production in particular industries, but would not sap global aggregate demand. Huang Yiping, dean of the National School of Development at Peking University proposed a credit scheme to finance exports to the global South. Beijing is also making moves to open its markets to exports from Africa. For Deese this competitive pressure is one more reason for Washington to move.

But, as Brad Setser points out in an illuminating twitter thread, the relative standing of the US and Chinese current accounts – whether or not they have a trade surplus and thus “funds to lend” - is an irrelevance from the point of view of marshaling the dollars necessary for a “Marshall Plan”.

We are not in the 1940s. Other than on the Chinese exchanges, the dollar is borrowed and lent freely. There is huge demand for American financial assets. So, if America wants to fund a dollar credit scheme, it does not need to be “earning dollars” through exports. It can fund a substantial Marshall Plan 2.0 by selling debt and then recycling the proceeds. This would not be a net flow of funding from the US to the rest of the world, but a recycling of dollars within the dollar-system managed by the new Marshall Plan authority. Think of it as a sovereign private equity fund. On a gigantic scale, this is how America’s balance of payments operates anyway. Foreign inflows to the US invested in safe assets like US Treasuries, off-set the purchase of riskier and higher yielding foreign assets by US investors. On balance, the US does very well out these flows.

If the US set itself up on this model to underwrite purchases of affordable and efficient green energy technology thereby promoting green industrialization worldwide that would make perfect sense. If, as Deese suggests, it leverages the public component by crowding in larger private lending that would amplify the effect and be fully in line with the synthesis of public and private finance that Daniela Gabor calls the ”Wall Street Consensus”. If it actually delivered on the promise of scaling global aid from billions to trillions, it might generate large profits for its private backers, but that would be a price worth paying for a great leap forward in the global energy transition.

This would make sense. But this isn’t Deese’s idea at all. His truly bamboozling proposition is that what the world really needs is American clean energy technology!

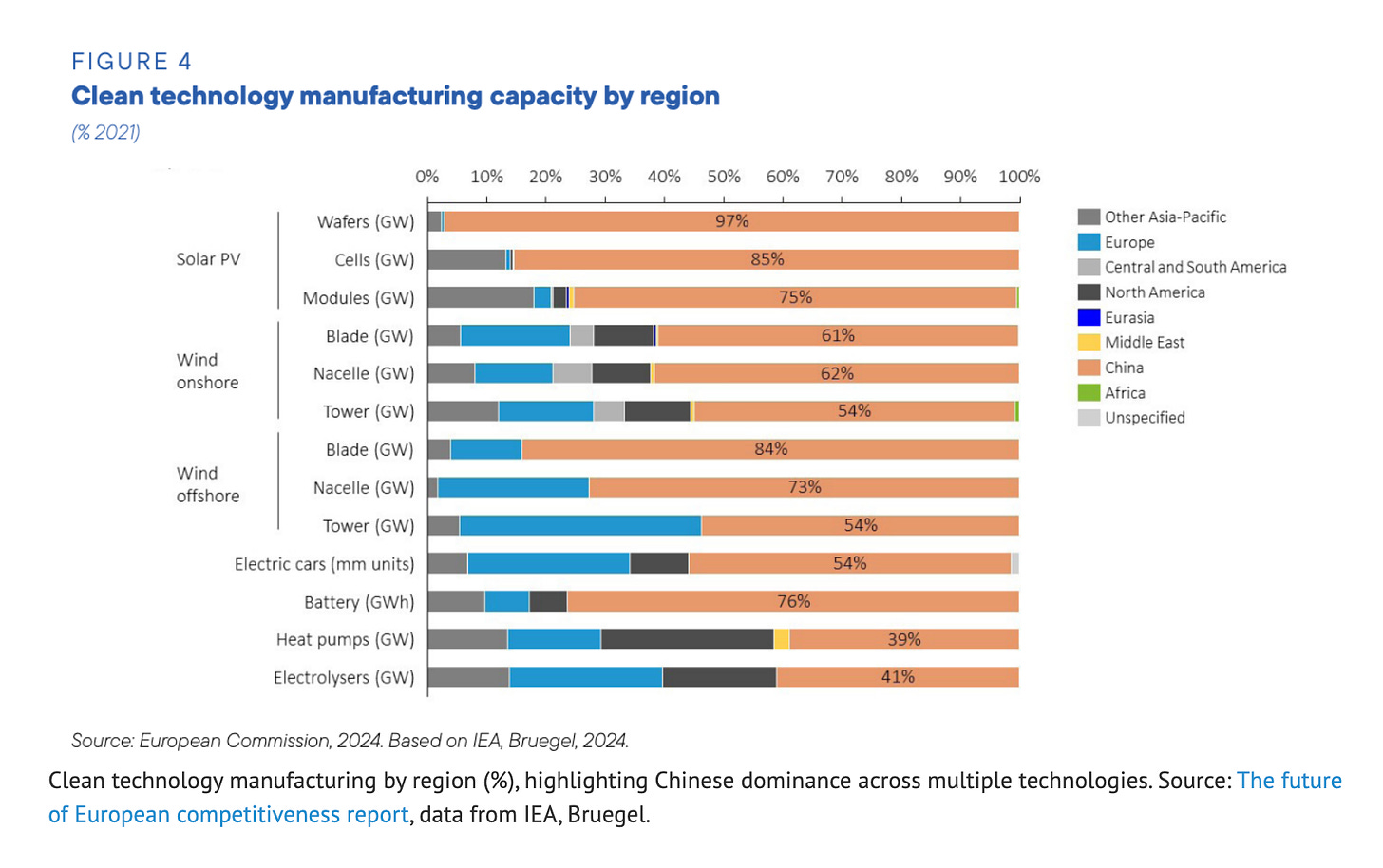

The obvious question is simply, what American clean energy technology?

Here is the breakdown in global production capacity in key clean energy technologies from the Draghi report on EU competitiveness.

As Deese gamely observers: “The good news is that most of the technologies necessary, from solar power to battery storage to wind turbines, are already commercially scalable.” Yup! this is true. But the problem from Washington’s point of view is that it is not the US that is leading that commercialization. But China. On a huge scale. Against US resistance.

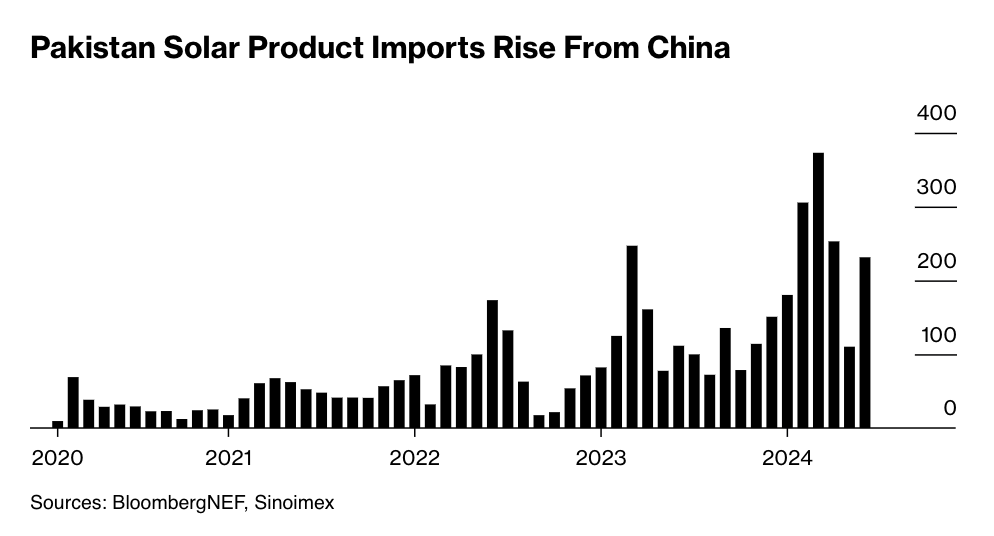

Take debt-ridden Pakistan, presumably a prime candidate for the clean energy Marshall Plan. It isn’t the US that is flooding the country with cheap solar panels. It is China. As Bloomberg reports:

Pakistan imported some 13 gigawatts of solar modules in the first six months of the year, making it the third-largest destination for Chinese exporters, according to a report by BNEF analyst Jenny Chase. Pakistan’s installed capacity to generate power is just 50 gigawatts.

What are the technologies that Deese sees his Clean Energy Marshall Plan promoting? They are a strange list: geothermal, hydrogen, carbon capture, nuclear.

At this point the verbal slight of hand becomes evident. What Deese is promoting is indeed a “Clean Energy” Marshall Plan, not a Green energy Plan.

Though some of Deese’s preferred technologies may matter in the long-term, none of them is widely expected to play an important part in the energy transition in the near term. And the fact that the US is a serious player in hydrogen, geothermal and carbon capture is not by accident. What they all have in common is that they are the favored “clean technologies” of US fossil fuel industries and widely regarded with suspicion with those interested in a comprehensive green energy shift.

The fossil fuel interests that stand behind hydrogen and carbon capture, are the same fossil fuel interests that have been favored for decades by US federal policy and since the 2010s have unleashed the fracking revolution, which under the Biden administration has made the USA into the largest producer of oil the world has ever seen. Both the American Petroleum Institute and the Chamber of Commerce have announced that they will line up to defend Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act against Republican repeal, specifically with a view to retaining its hydrogen subsidies. The Deese proposal is fully in line with this fossil-inspired vision of “clean energy”.

These same fossil fuel interests, incidentally, were also favored by the Marshall Plan. Contrary to Deese’s lop-sided emphasis on the Marshall Plan as an industrial policy instrument, what the Europeans needed in the first instance in 1947 were dollars to fund purchases of food and commodities, followed at a later stage by manufactured imports. As a CRS report summarizes it:

The content of the dollar aid purchases changed over time as European needs changed. From a program supplying immediate food-related goods—food, feed, fertilizer, and fuel—it eventually provided mostly raw materials and production equipment. Between early 1948 and 1949, food-related assistance declined from roughly 50% of the total to only 27%. The proportion of raw material and machinery rose from 20% to roughly 50% in this same time period.24

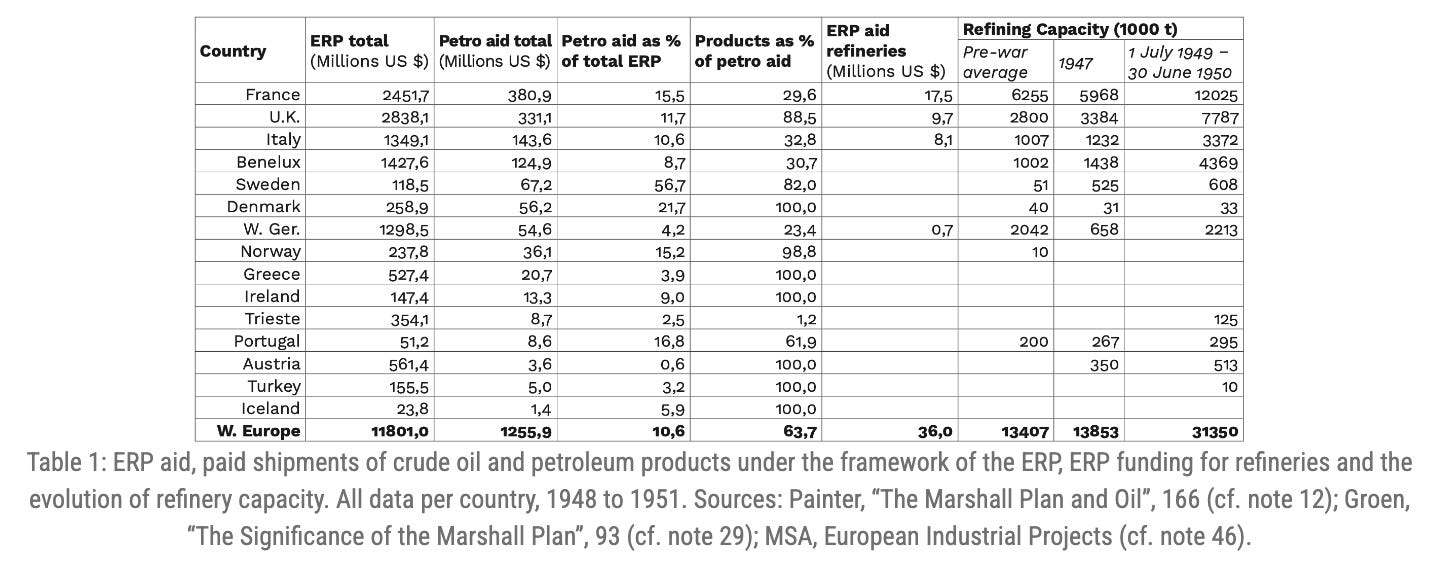

Amongst the commodities that Europe needed was oil. As Gross, Melsted and Chachereau show us in a recent paper, US aid after 1947 contributed materially to Europe’s growing oil imports and the expansion of refinery capacity.

Of course, such matters of fact are not going to stop the Marshall Plan myth being recycled for contemporary purposes.

But if such arguments aren’t about history, or the actually existing green energy transition, what purpose does Deese’s talk of a Clean Energy Marshall Plan serve? The word in the beltway and beyond is that this is really about power in Washington itself.

Deese’s proposal is not the only proposal of its kind to emerge over the summer. In recent weeks Jake Sullivan and Daleep Singh have let it be known that they are holding regular meetings and “brainstorming sessions” about setting up a Sovereign Wealth Fund.

Once again this kind of talk in Washington involves a surreal inversion of the logic of actual sovereign wealth funds. Actual sovereign wealth funds are mechanisms for chronic surplus countries to ring-fence their export revenue and to redeploy it within the dollar system, without producing excessive distortions in their home economies. It makes little sense to transfer such a model to the USA, which is the master of the dollar system, the issuer of the largest pool of safe assets and an economy, which runs a chronic trade deficit (Facts, which as Michael Pettis would point out, are directly related to one another).

But, once again, macroeconomic logic is not the point of Sovereign Wealth Fund talk. Of course the USA could fund a “sovereign wealth fund” in the same way as it could fund a “Marshall Plan”. It could simply borrow at relatively low rates and hope to make investments that made a better return. That is what financial professionals do, every minute of every day.

What makes these proposals something other than totally redundant, is to understand them as bids for autonomy within America’s deadlocked political system. What the masters of “economic statecraft” want, is freedom of action beyond the constraints of Congressionally mandated monitoring and regulations of various kinds. What they want to overcome is the all too evident incapacity of the US to deliver anything remotely like the original Marshall Plan, or deploy national assets in the way that Sovereign Wealth Funds do.

It is telling that in the Foreign Affairs article, where Deese’s proposal becomes truly fleshed out an animated is precisely on this score:

To be effective, the Clean Energy Finance Authority would need to be big yet nimble. Not only has the United States lagged other countries in offering public capital to lead the energy transition, but its financial support is also unnecessarily inflexible. Officials in foreign capitals joke that the United States shows up with a 100-page list of conditions, whereas China shows up with a blank check. The United States’ current financing authorities are constrained by byzantine rules that block U.S. investment that could advance its national interests. For example, the U.S. Development Finance Corporation, which invests in projects in lower- and middle-income countries, cannot invest in lithium processing projects in Chile because it is considered a high-income country, yet companies in the low-income Democratic Republic of the Congo often find it impossible to meet the DFC’s stringent labor standards. … Promising models for a Clean Energy Finance Authority also exist. Domestically, the Department of Energy’s Loan Program Office rapidly expanded its capabilities, approving 11 investment commitments to companies totaling $18 billion in the past two fiscal years (versus just two commitments in the three years before that). Internationally, the DFC expanded its climate lending from less than $500 million to nearly $4 billion over the last three years. … The most effective aspects of these examples should be harnessed together under the Clean Energy Finance Authority, which should have a versatile financial toolkit, including the ability to issue debt and equity. It should be able to deploy this capital in creative arrangements, such as by blending it with foreign capital and lowering risk premiums with insurance and guarantees. It should draw on, not re-create, the Department of Energy’s expertise in assessing the risks and benefits of emerging technologies, such as advanced nuclear energy, hydrogen power, and carbon capture and storage. The Clean Energy Finance Authority could be managed by the U.S. Treasury Department, in light of the latter’s experience in risk underwriting and financial diligence, and given the mandate to coordinate closely across agencies. With nimble, market-oriented financing capacities, the Clean Energy Finance Authority would be able to accelerate and initiate, not impede, financial transactions.

One pot of money, which the exponents of late-stage Bidenomics reportedly have their eye on, is the Treasury’s Exchange Stabilization Fund, which also has a deep history that goes back to the New Deal era. In the case of the ESF it was set up to manage the dollar exchange rate after it was unpegged from gold in 1933. Like the other pots of money the economic strategists would like to get their hands on, the ESF has the virtue of being at the Treasury’s ready disposal.

Seen from this angle, appeals to the myth of the Marshall Plan or ideas like a Sovereign Wealth Funds are rhetorical devices with which America’s economic statecrafters hope to clear a free path through political and administrative deadlock, to gain nimbleness and freedom of action, to do something … anything!

The sinews of America’s military, financial and technological power remain strong. If they are combined, as in targeted financial sanctions, they can in limited cases be highly effective. But when it comes to the bigger strategic picture the limits of America’s strategic room for maneuver are becoming painfully obvious. Talk of Marshall Plans should not be confused with actual strategies of global power, or coherent visions of global development. Such talk points, rather, to what is absent – a realistic vision of America’s role in a rapidly developing multipolar world and the political majority within the United States to back that vision with real resources and real power.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates.

> the fact that the US is a serious player in hydrogen, geothermal and carbon capture is not by accident. What they all have in common is that they are the favored “clean technologies” of US fossil fuel industries and widely regarded with suspicion with those interested in a comprehensive green energy shift

Adam, you go too far in claiming the mantle of "those interested in a comprehensive green energy shift" as disjoint from those trying to scale hydrogen, geothermal and carbon capture as real solutions. The existence of hydrogen and CDR greenwashing tactics by fossil fuel interests does not invalidate excellent work by Fervo / Eavor / Dandelion / Quaise etc or the many serious-albeit-yet-to-scale efforts on permanent capture and sequestration.

More broadly, you imply (not for the first time) that the cause of non-leadership by America is fecklessness on the part of Democratic leaders rather than the absence of social coherence and solidarity on the part of the American electorate.

The work before us is to scale solutions and create the solidarity that will help us pay for them, not to scold leaders stuck awkwardly trying to straddle the gap between where our political economy is and where it needs to be.

1) The post war European economies have by now been studied well enough to say that the effect of the Marshall plan was at best moderate.

St Louis FED: Marshall Plan May Not Have Been Key to Europe’s Reconstruction

July 01, 2021 https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2021/july/marshall-plan-not-key-to-europe-reconstruction

'Together this suggests that the Marshall Plan and IBRD lending played a smaller role in European reconstruction than what has been commonly believed. Instead, Europe was primarily responsible for rebuilding its own economy.

The figure below shows the amount of aid each country received from the Marshall Plan in 2019 dollars. The United Kingdom and France received the most at $33 billion and $28 billion, respectively. However, these amounts represent no more than 5% of the gross national product of each recipient nation.4'

Indeed another study i remember showed the UK in particular getting a shot n the arm while other European countries manifested a more muted response.

2) Fear of losing (some of) Europe to the communist parties no doubt fueled American politics but stating that economic hardship was/would be the only driver for European's favourable pov on the communists is only half the story. As the de facto slayer of the Nazi's the USSR was held in quete high esteem in broad circles. While in most occupied countries it had been the local communists who, along with Christians, put up most of the resistance - and who were executed for it.

3) The Marshall plan díd produce fantastic stories. This is a great article about the gigantic American donkeys that were send to Greece:

When the American People Sent 15,000 Animals to Revitalize the Greek Countryside

https://pappaspost.com/when-the-american-people-sent-15000-animals-to-revitalize-the-greek-countryside/