Chartbook 316: Putting the unipolar epoch of climate politics in its place. Or, the mixed economies of the climate crisis (Carbon notes #14)

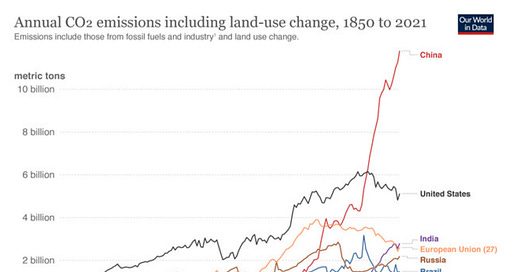

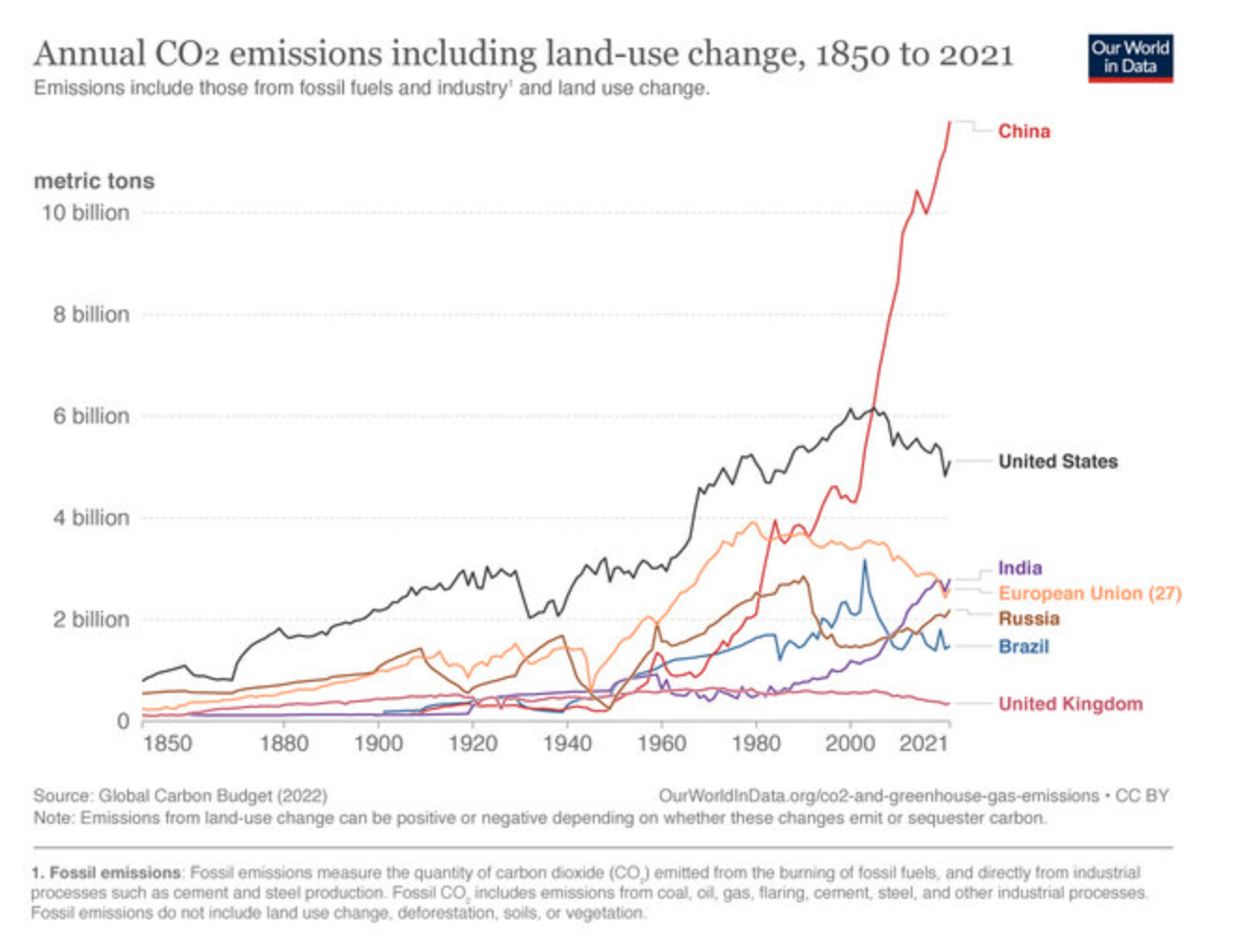

Right now one of the challenges for climate politics in the West is to come to terms with the fact that it is CCP-led China that dominates the global emission’s balance.

At least rhetorically, the spokespeople of the US and Europe still talk of climate leadership, of hustling China into accelerated action and of setting an example for Beijing to follow. Some even fantasize about “green Marshall plans”. The reality is that both in terms of emissions and green energy investment, China is now the decisive force and there is little reason to believe that Beijing’s policy is conditioned to any serious extent on the erratic and inconsistent decision-making of the West.

China’s emissions overtook those of the US in 2006, slightly later on a consumption basis allowing for emissions exported to the West. Since 2012, under Xi Jinping’s rule, climate has been given an increasingly prominent role amongst the regime’s objectives.

The West faces the disorientating prospect that leadership on the climate issue will be taken by an authoritarian regime that sees itself as realizing “21st-century Marxism”, manifestly willing and able to override the interests of private capital, both large and small, wherever it sees fit. Western policy-makers also profess to believe that this Chinese regime is bent on global power, or at least on challenging what is left of US hegemony. Beijing certainly seems bent on revising the Cold War order in East Asia. Against this backdrop, Western capitals increasingly characterize China’s leadership on green energy as part of its geopolitical power play.

This is disorientating for the tradition of progressivism that discovered the climate crisis in the 1980s and by the 1990s had taken to defining “managing the climate crisis” as the acid test of governmental rationality for Western democracies. Though this often went unspoken, this claim tended to be framed by the assumption that if only the US and Europe could get their act together, then they could actually “save the planet”. Historical agency on climate was the West’s responsibility, but also its privilege.

Now, in a new era of “Cold War”, it is China that is decisive on the climate issue. So the question is: What does it do to the historical legitimacy claims of democracy if it is the CCP regime that is actually delivering the goods on the global energy transition?

Beyond those preoccupied with governance in the West, China’s rise also poses puzzles for critical political economies of the climate crisis, especially those that insist on the centrality of “capitalism” to their interpretation. All too often, those approaches are rooted in the assumption that ultimately, it is American fossil fuel industries that hold the future to ransom. The image of fossil capitalism that is conjured up, is ExxonMobil.

That is anachronistic. For the last quarter century, it has not been Western capitalism and in particular it has not been publicly traded Western oil majors that have been the largest drivers of emissions growth. The Western oil majors do play an outsized and disastrous role in new oil and gas exploration. The US fracking boom is an event of global significance that changes the dynamics of the oil and gas markets. But the principal drivers of current emissions have been giant emerging market coal conglomerates and state-owned or semi-state-owned energy firms, emblematically in the oil and gas states of the Middle East. They feed off the extraordinary growth of global energy demand drive by CCP-led China.

These are highly distinctive developmental regimes, above all in China that are quite different from the developmental regime in the US, which has fostered the Texas oil patch, or the multinational operations of the European majors, BP, Shell and Total.

Given this proliferation of different “energy states” and political economies of energy extraction and use, it is a crude and unhelpful simplification to reduce the actually existing climate crisis to a flat world of “capitalism” pure and simple. We are far better off starting from the assumption of a “mixed economy of energy” driven by uneven and combined development centered on East Asia industrialization and urbanization.

It is tempting to say that this shift from West to East is unprecedented. But, in fact, that would be a mistake. One of the surprises, if you look back to the birth of modern global climate politics in the 1980s and early 1990s, is that then too the political economy of the crisis was understood as “mixed” and polycentric.

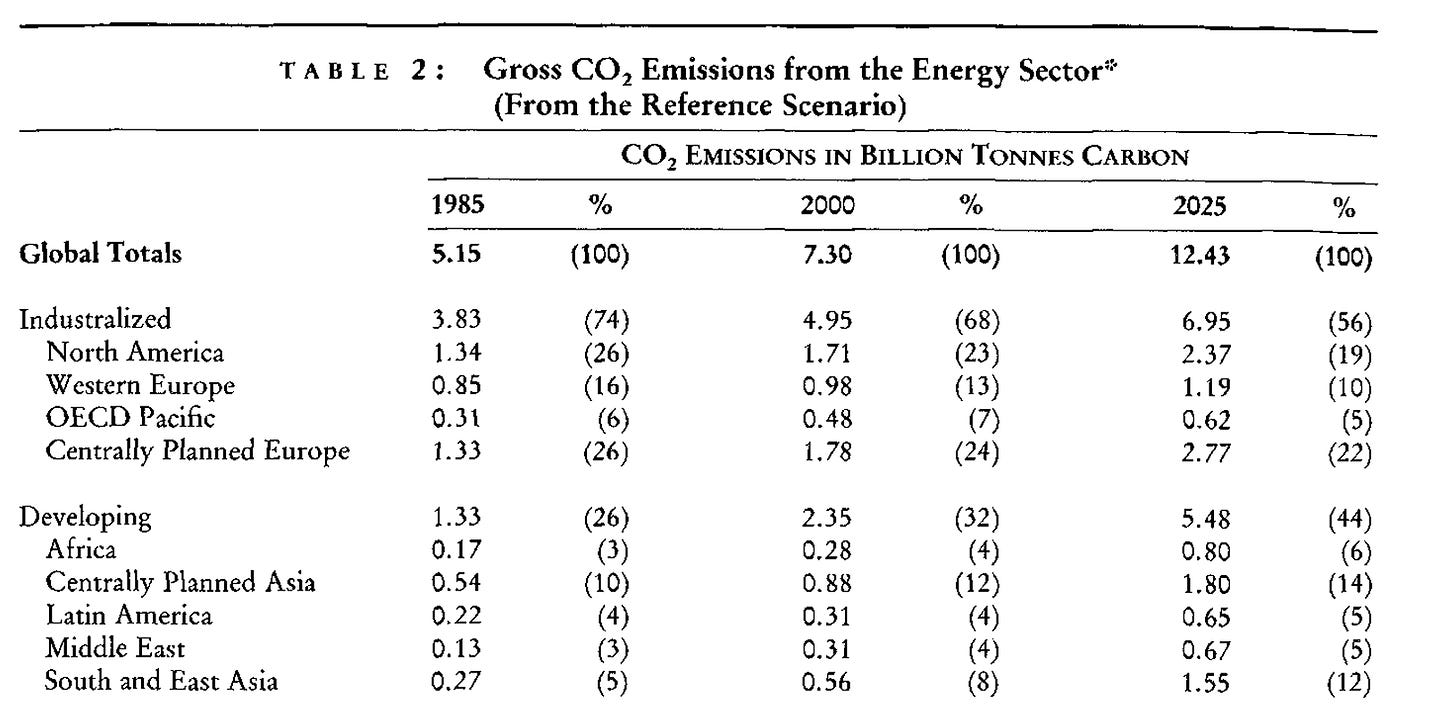

This comes out very clearly, if we examine the economic scenarios that underpinned the first wave of analysis commissioned by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change between 1990 and 1992.

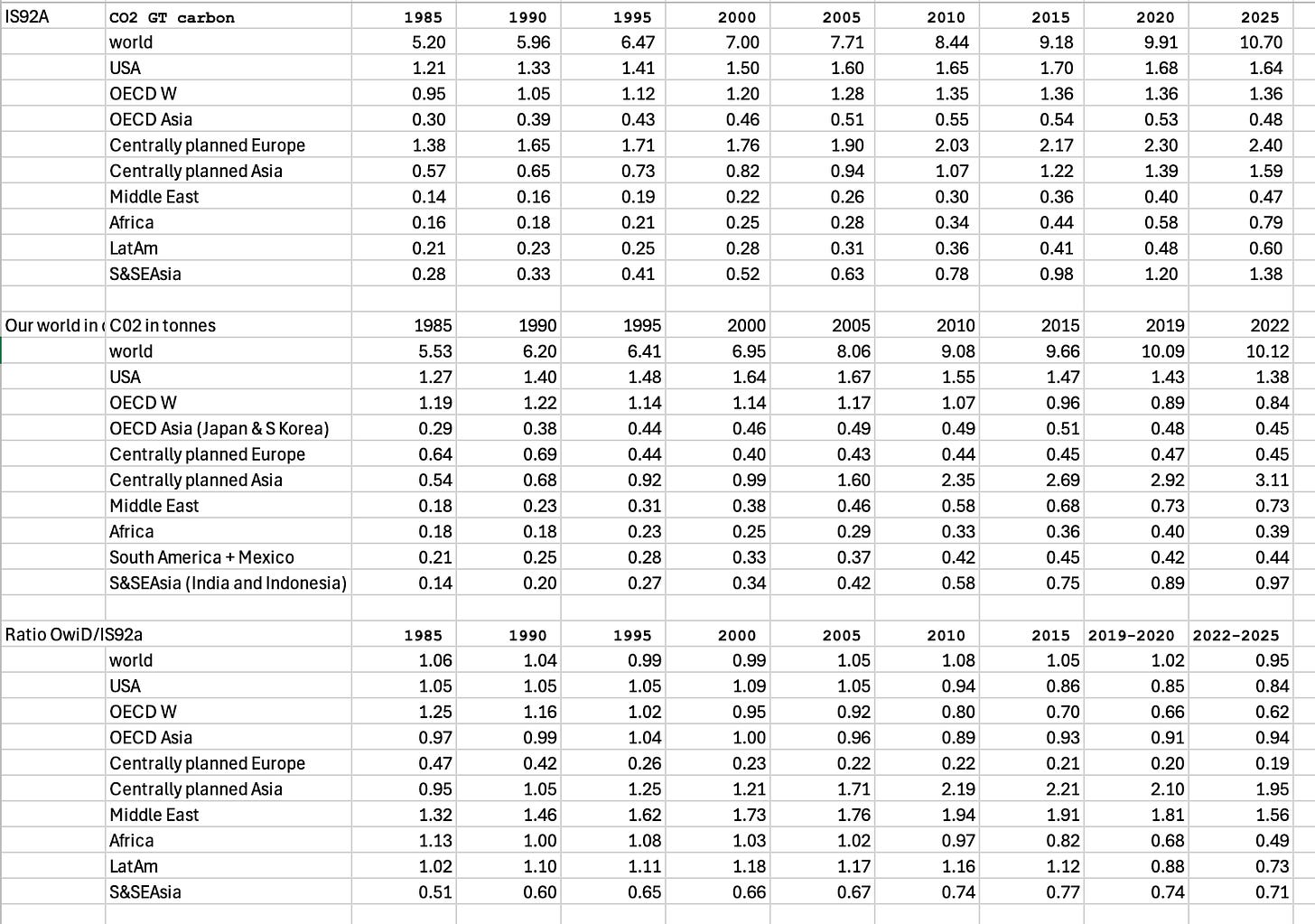

The scenarios drawn up by multinational teams of experts coordinated from research centers in the Netherlands and the US were based on projections from the previous decades of economic growth supplemented by guess-work about likely future trajectories. The central “reference scenario” for 1985 to 2025 first outlined in 1990 is shown below. If these figure look too low to you, this is because they are given in terms of pure carbon rather than CO2. To get from these numbers to CO2 numbers, you multiply by a factor of 3.67.

Table 1: 1990 IPCC CO2 emissions “reference” scenario

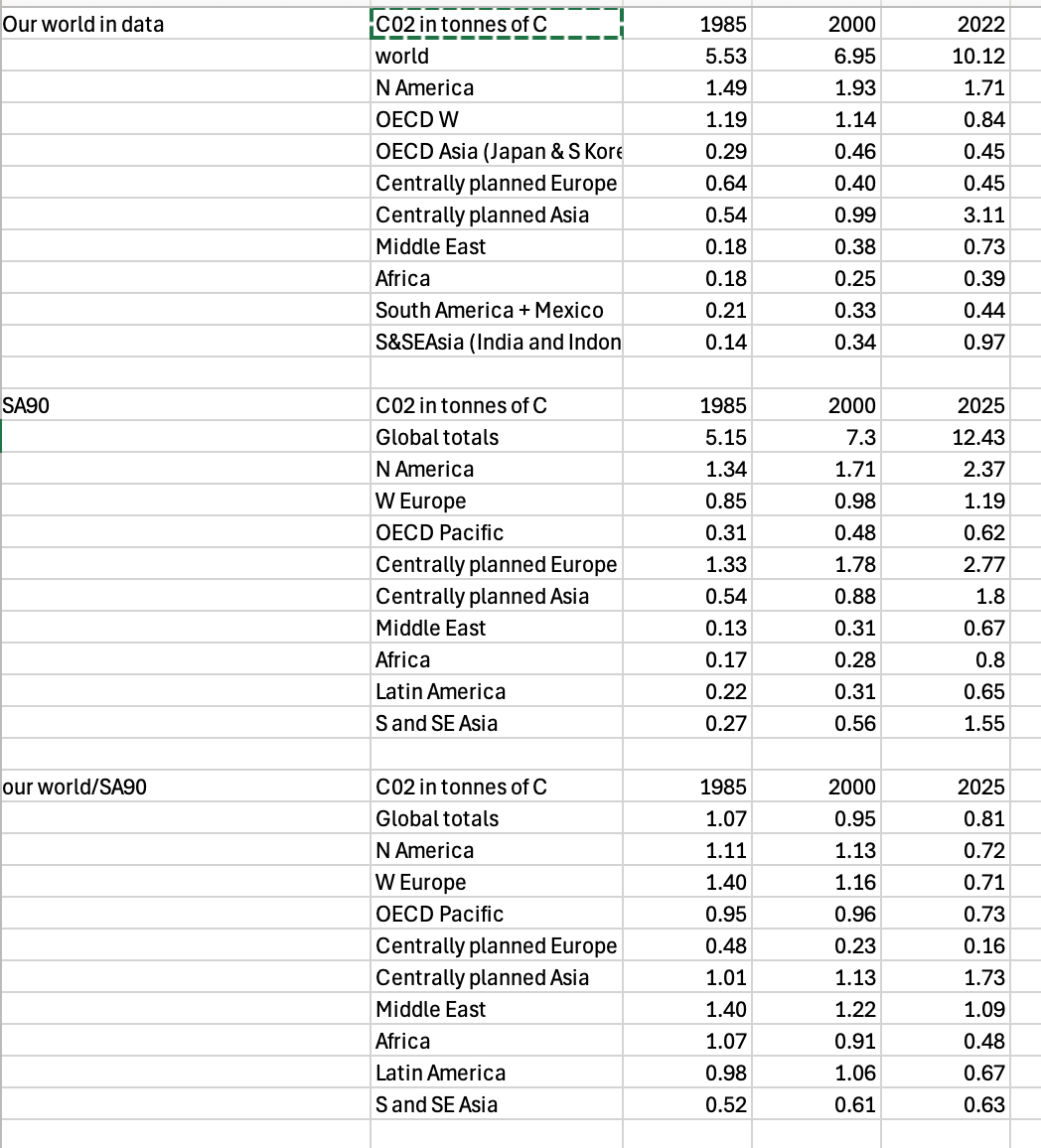

One striking thing about the top line - the global totals - is how close this central reference scenario, drawn up in 1989-1990, comes to the actual development of global emissions through 2000. In Table 2, I compare the IPCC reference scenario from 1990 with its forecasts out to 2025 to the actual record of emissions as documented in Our World In Data.

Table 2: Comparison of SA90 IPCC scenario of 1990 with real world outcome

As can be seen in Table 2, after 2000 the IPCC’s reference scenario tends to overshoot the actual course of emissions. Since this is a scenario that assumes “business as usual” i.e. the continuation of 1980s trends, the scenario’s overshoot is reassuring. Furthermore, please note that in the final column, I am comparing data for 2022 with those for 2025. So, given growth trends, we should expect the scenario to be some way ahead.

As we will see, the revised forecast issued two years later in 1992 was even more accurate.

What catches the eye in the 1990 scenario, is the classification of economies down the left-hand side. Two lines are reserved for the “centrally planned economies” of Europe and Asia. This reminds us that if a Cold War with China looms large today, global climate policy was born in the 1980s in the final stage of the confrontation with the Soviet Union. And like China today, the Soviet bloc was a large part of the emissions balance, on a par with “the West”.

In the world economy in the 1970s and 1980s, the Soviet bloc emerged as a large supplier of oil and gas. But, at home, the Comecon economies relied on coal-fired electrification, a model that China would first follow and then take to a new level. The result were huge emissions and regional pollution that spread acid rain across central Europe.

According to the IPCC analysis, by 1985 the Soviet bloc in Europe was more or less matching the CO2 emissions of North America. It was exceeding the USA. By 2025, the IPCC expected the emissions of the Soviet bloc to be well ahead of those of North America. In the future, as it was projected by the IPCC in 1989 and 1990, effective global climate action would depend on negotiation across the Cold War front line between the US and Soviet power blocs.

You might say that it was Cold War dynamics that upset the 1990s reference scenario. The IPCC analysts, like everyone else, failed to anticipate the full-scale collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the vast surge in Chinese emissions, especially from 2000 onwards. This is by far the largest difference between the future scenario and the actual outturn. But, if we ignore the Sino-Soviet split and aggregate the centrally planned European and Asian economies, then, as Table 1 shows, their combined share in the IPCC’s 1990 forecast for 2025 actually approximates to within a few percentage points, the combined share of global emissions attributable to China and Russia today.

Based on the experience of the 1970s and 1980s, the IPCC scenario was prescient in suggesting that the climate crisis would be driven by a “mixed” economy of western and non-western models of industrialism and urbanism. Where it erred was in assuming that the big driver of emissions would be a Moscow-led bloc rather than China. It should also be noted that the forecasters also overestimated future emissions growth in both the USA and Western Europe.

In 1991 the scenario planners were asked to revise their outlook in light of the first Iraq war and the fall of the Soviet Union. Ironically, the effect of that collapse was not to shift the basic balance in the forecast. The end of the Cold War in Europe put the United States in charge. But the forecasters now assumed that the economies of the former Comecon, relieved of the corset of the Soviet regime, would grow faster. Even if they abandoned or modified Soviet-era energy systems, their emissions would be highly significant. In the so-called IS92A scenario - the central business as usual scenario employed by the IPCC and others in the 1990s - emissions from the bloc labeled as “centrally planned Europe” are projected to outstrip those from the USA.

NB: In these tables the thing to track is the relative movement of the series for the “centrally planned European economies” not their absolute level. Matching post-1991 data to pre-1991 regional classifications for the Soviet space is a major headache and I am working at cleaning up these data. Right now the trajectory of the region is being proxied by the data for “Russia” in the database supplied by Our World in Data. If anyone knows a source that covers the transition in the post-Soviet in a more adequate way I would be much obliged. The crucial point is that Russia’s economic collapse and deindustrialization in the 1990s crushed emissions.

The point is that with historical perspective the current situation in which the climate problem is multipolar and China is the pivot seems less anomalous. At the moment when global climate politics was born, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the outlook was structurally similar. In 1992 the IPCC was still describing the climate crisis in terms of a “mixed economy”.

It was only in the course of the 1990s that the fossil-fuel-driven climate crisis was reframed in unipolar terms, as primarily a US-driven phenomenon that could be adequately summarized in political terms by reference to Republican “climate deniers” and ExxonMobil as the great satan of fossil fuel politics. North-South political dynamics from the Rio conference in 1992 onwards, the US refusal to ratify Kyoto and the “oil wars” of the Bush administrations, compounded this unipolar reading. The efflorescence of Marxisant writing on the climate crisis and long durée histories of the “capitalocene” have contributed to the intellectual charisma of this Western-centric reading. For political purposes, the imagery continues to serve useful political purposes today. But, both as history, when we approach the mixed economy of energy in the postwar “great acceleration” , and as an analysis of the climate crisis in the 21st century it is fundamentally misleading. It should be understood as an epochal political and intellectual accompaniment to the unipolar moment of the 1990s, an era which is now behind us. To the extent that that vision of the climate crisis continues to resonate, whether in affirmative and critical takes on Western “climate leadership”, it is a marker of our disorientation.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates.