Chartbook 307 To live or not to live with polycrisis: The USA, Mexico and the need for a regional policy in Central America and the Caribbean.

The attack line from the Republicans is predictable: Kamala Harris was Biden’s border tsar. The crisis on the border with Mexico shows that she failed. So too is the response from the Democrats: No, the vice-president never was in charge of the border. Her role was to address the root causes of migration from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. No one can blame her for failing. It was mission impossible. The striking thing about this retort is not that it is unreasonable, but that it sets such a low bar. Whereas for the Republicans the desperation in Central America is reason to seal the border even more firmly, for the Democrats the deep-seated nature of those problems is an excuse. Apparently, no one expects Harris or anyone else to succeed in addressing the poverty and insecurity in the region. Shrugging its shoulders, the US settles down to live with polycrisis on its doorstep.

A visit to Mexico City and the Harris candidacy prompted me to think about how the US political class relates to the polycrises on its doorstep. What troubles me most is not the lack of simple answers, or quick fixes, but the indifference, a state of mind fed by resignation. I wrote an op-ed for the FT about it.

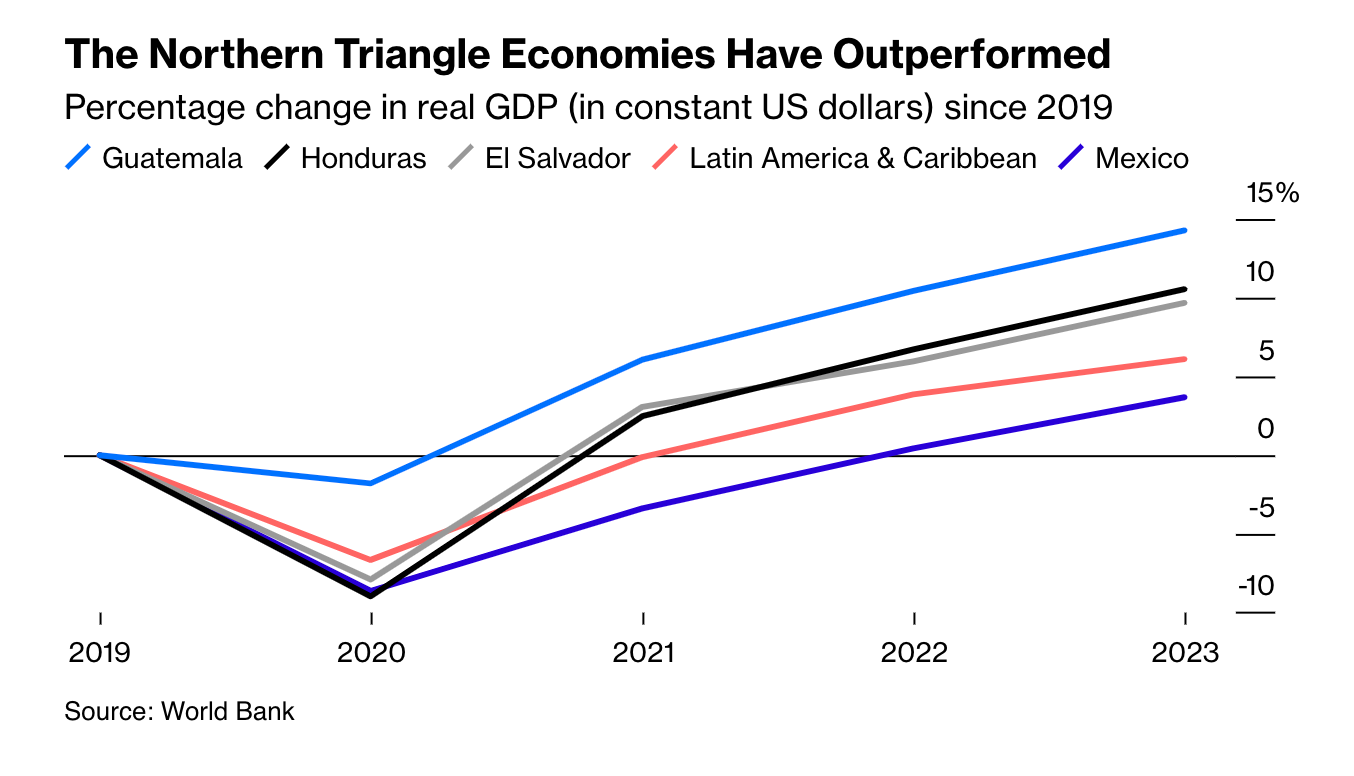

Of course, the story is not all bleak. As Justin Fox points out in a Bloomberg column that appeared today, there has actually been (some) economic growth in the Northern triangle (El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala).

But, the structural problems and the misery of many millions of people in the region go deep and will not be remedied by a few percentage points in GDP growth.

The range of factors impacting the most struggling societies and people in Central America, the Caribbean and Latin America cannot be reduced to a single cause. But here are a few:

Inequality and poverty are deeply entrenched. The Inter-American Development Bank teamed up with a range of academic and think tank partners to produce a collection of studies of inequality in the wider region. Its results confirm that:

Latin America and the Caribbean is the world's most unequal region. The 10% highest earners make on average 12 times more than the poorest 10%. This compares to a ratio of 4 on average for developed countries in OECD. In addition, one in five citizens of Latin America and the Caribbean is poor.

In Colombia, Chile and Uruguay, around one percent of the population controls between 37 and 40 percent of total wealth, while the poorest half of the population controls only one tenth of the wealth. The level is much higher than the 20% to 30% range western Europe and Scandinavia. It is in fact close to the United States (42%).

Between 1990 and 2014 the region saw its inequality reduced. Progress since has stalled.

The region is home to countries with extremely high-income inequality such as Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Panama and Honduras. But it also includes Bolivia, Dominican Republic, El Salvador and Uruguay, where income gaps are on a par with the United States.

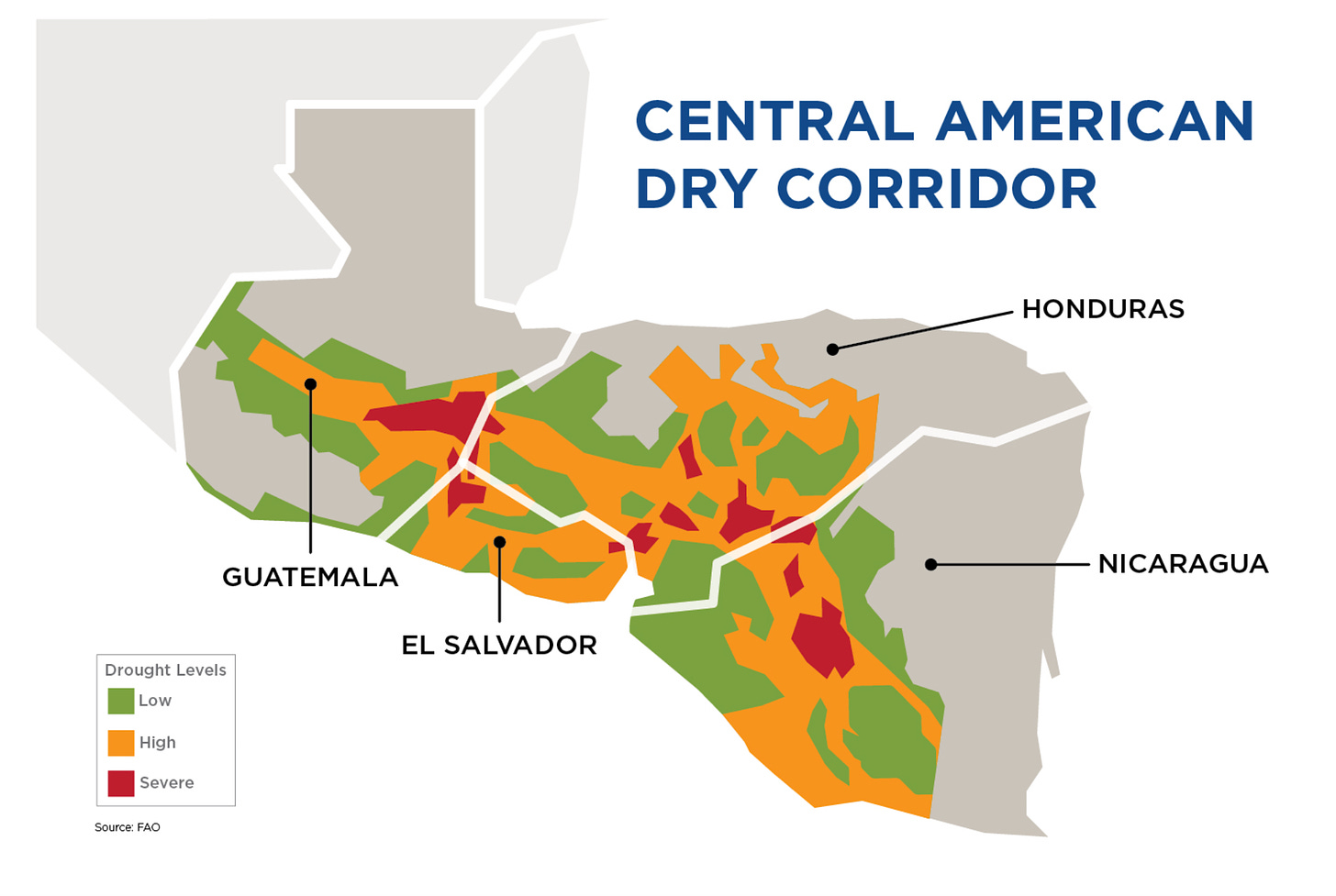

The study confirmed that regional and urban-rural differences are crucial to inequality in the region. In particular, it emphasized the huge gulf within the countryside between the richest and poorest farmers. A contributing driver of those inequalities in Central America is the climate crisis that is making itself felt in dire conditions in the so-called Dry Corridor. The Corridor is home to 10 million people. 73 percent of them live in poverty. At least 500,000 are in conditions of very serious food insecurity.

Source: CRS

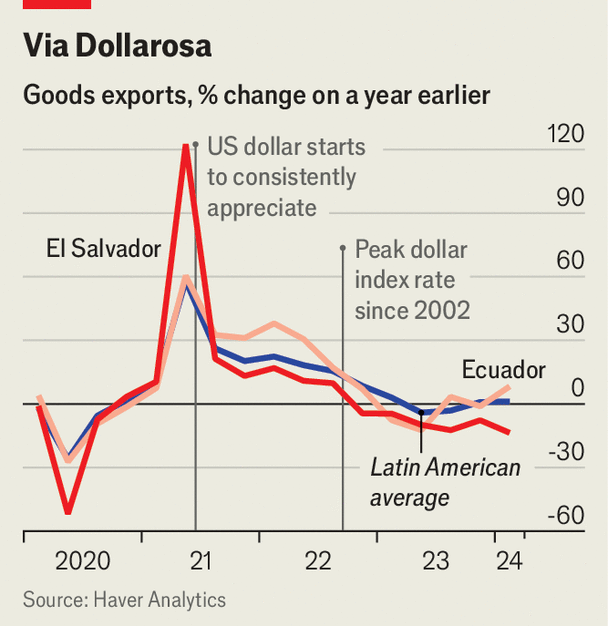

Macroeconomic stability has been a problem for many countries in the wider region. Dollarization provides stability of a kind to Ecuador, Panama and El Salvador, but at a price that gets heavier as the dollar is on an upswing.

There are some other factors, too. Ecuador has suffered a destabilising wave of gang violence. Following protests, Panama’s government closed a big copper mine, which has shaved perhaps 1% off its gdp. And unpredictable policymaking in El Salvador under its authoritarian president, Nayib Bukele, has shaken investment. The strong dollar adds to all these difficulties. Adopting the dollar means renouncing an independent monetary policy and forgoing the option of responding to external shocks by devaluing the currency. Central banks still exist in Ecuador and El Salvador, but they do not control the money supply or set interest rates. Instead, economies have to find other ways in which to be flexible and competitive. But in Latin America that is rarely the case. Dollarisation encourages greater economic integration with the rest of the world because it cuts the transaction costs involved in trade. But if goods and services are uncompetitive, it is tougher to make the most of potential opportunities. A recent study published in Applied Economics, a peer-reviewed journal, found that adopting the dollar had failed to create any major positive trade effects for Latin America. … These difficulties should give pause to Javier Milei, Argentina’s president, who campaigned on adopting the dollar and shutting down the central bank.

Source: Economist.

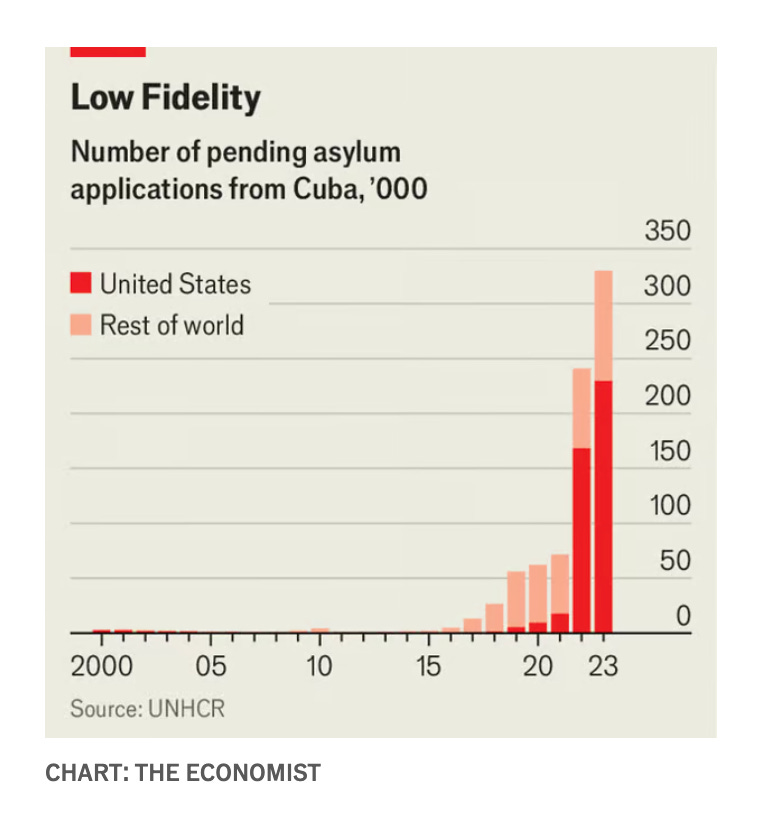

Then there is Cuba. Caught between the hammer and anvil of the entrenched regime and US sanctions, its population are suffering a dire economic and social crisis.

… the communist government is losing control of the country—which is not to say the regime is about to fall. .. The government is unable to provide even the basic canasta (basket) of goods for its people, let alone anything else. The result is growing inequality, unrest and emigration. In the two years to the end of 2023 a tenth of the population of 11.2m left.

Economist

Even more grievous than the situation in Cuba is the crisis in Haiti, where a new provisional government is struggling to regain control of the capital city at a minimal level. In June, the UN reported that “escalating gang violence and political instability have forced a record 578,074 internal displacements in 2024 including over 310,000 women and girls and 180,000 children, more than double the figure from 2022, making it the country with the largest number of displacements globally due to crime-related violence.”

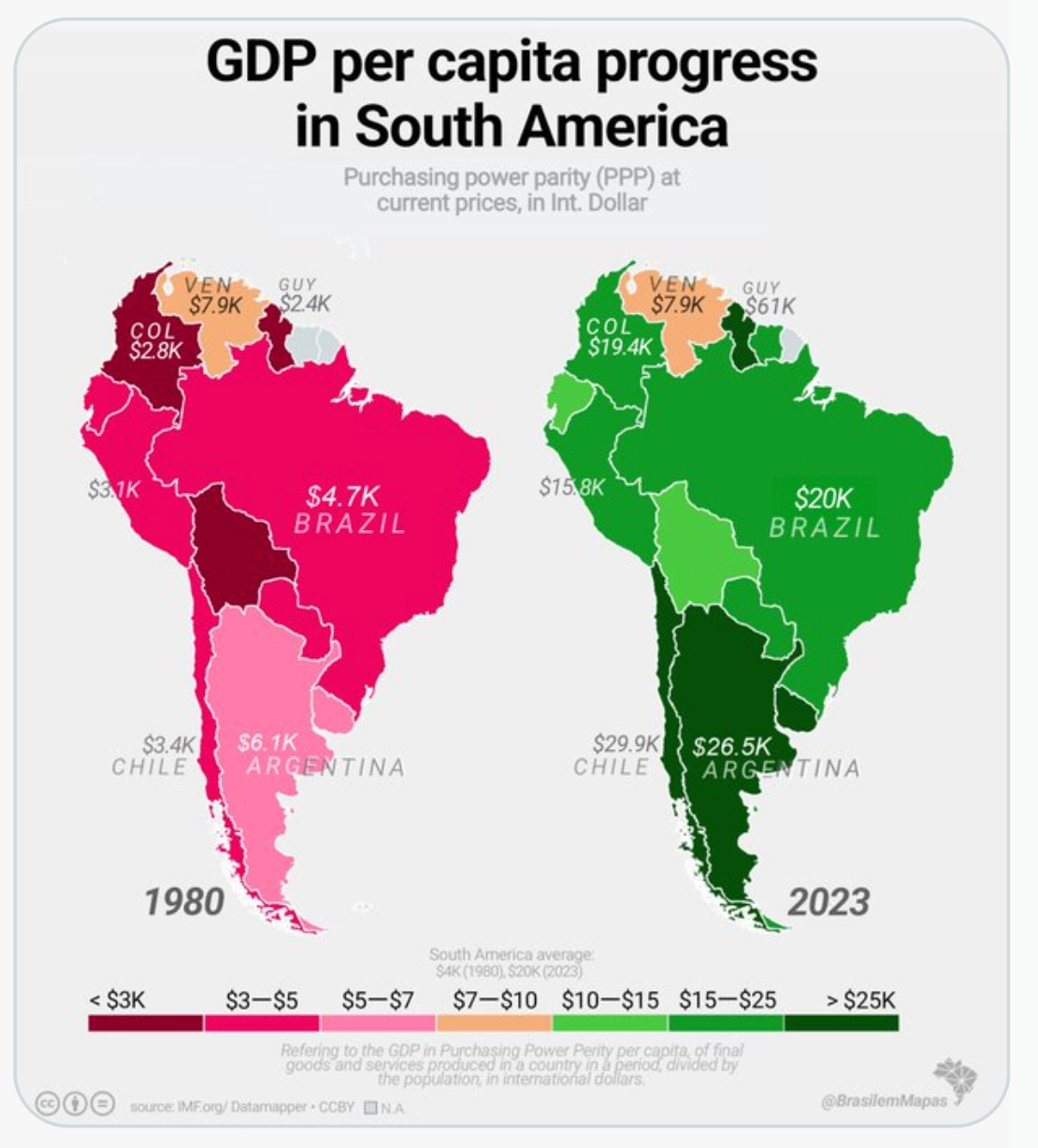

The largest crisis in the wider region in terms of scale, duration and spillover effects is in Venezuela. Long-run economic data put the current misery in perspective. In 1980 Venezuela was hands down the richest country in South America (in per capita gdp terms) and far ahead of Central America. Now its people join the desperate refugee and migration flows to Colombia and to the North.

What resources does the US muster to meet these multiple crises on its doorstep and in the wider region?

Figures for US assistance to the region compiled by the Congressional Research Service show how modest the effort is. These figures are in constant dollars. Imagine what this would look like as a share of GDP! Alternatively, compared these figures with the tens of billions of dollars raised to support Ukraine or Israel. The US assistance budget for Latin America and the Caribbean is an expression of indifference. Even leveraged with private funds it is entirely insufficient to meet the crises in the region.

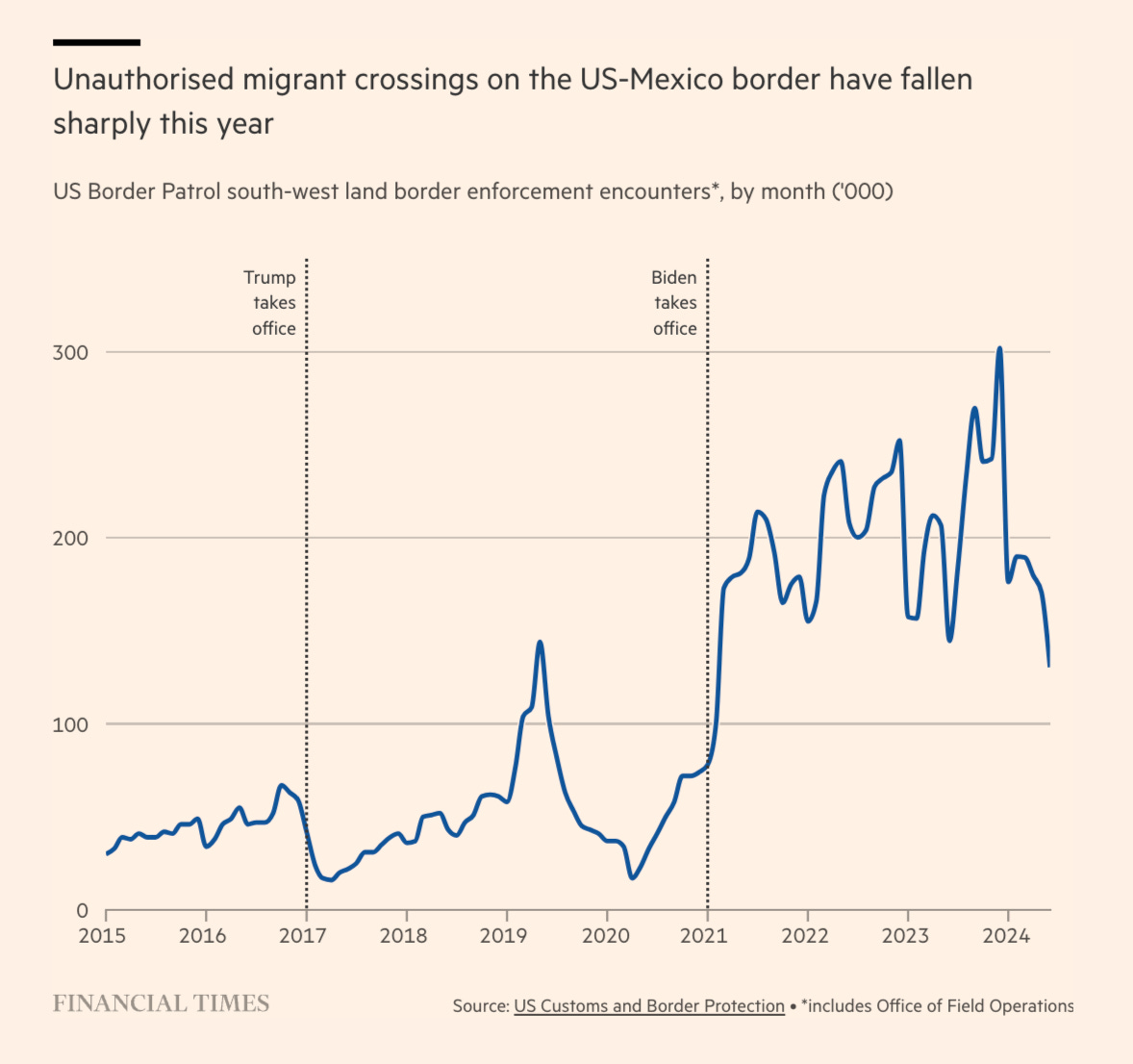

The central priority of US policy is to contain migration. As this fantastic FT report by Michael Stott and Christine Murray pells out, this is above all a matter of diplomacy with Mexico.

On December 21 (2023), the situation on the 2,000-mile US border with Mexico was critical. Every day that month, thousands of migrants were sneaking across the frontier, overwhelming border officials and forcing the closure of legal crossing points. Republicans were weaponising the crisis and President Joe Biden needed a quick solution. Biden called the one person who could help him quickly, Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, and demanded action, dispatching a team headed by Antony Blinken, secretary of state, to Mexico City. López Obrador’s government quickly restarted deporting and busing thousands of migrants from northern Mexico to the south, measures it had previously halted for lack of money. Unauthorised border crossings fell sharply in the following months from December’s record level of more than 300,000 and last week Biden was able to boast that they were now lower than when Donald Trump left office, although this claim has been disputed. The episode showed how heavily the administration has depended on López Obrador for help with stemming migration, an issue on which Republicans have constantly attacked Biden and vice-president Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic nominee. … (Biden’s ambassador) Salazar arrived in Mexico City with a clear objective. “His instruction from Biden was to get up close and friendly with Amlo,” another ambassador in Mexico says, referring to the Mexican leader by his initials. “The Americans were almost intimidated by Amlo.”

“López Obrador ran rings around us on trade, foreign policy, Venezuela, migration and counter-narcotics co-operation,” rues a former US state department official, who asked to remain anonymous given the sensitivity of the topic. If Mexico morphs into an illiberal democracy on its doorstep, there will be three winners: China, Russia and Cuba “While every nation prioritises its national interests, given that Mexico is our biggest trading partner and impacts the United States in so many ways, our failure to develop much beyond the transactional relationship we had under Trump is noteworthy.” Castañeda traces what he calls a US indifference to Mexico’s domestic politics back to the chaos in the 1920s following the Mexican revolution and “this sort of Faustian pact that the Americans wrote subconsciously with the Mexicans”. “As long as the place is stable, as long as core American interests are not threatened, meaning property and people, let the Mexicans govern themselves any goddamn way they want”.

As is too often ignored in the USA, the problems of the regions are not only theirs. Mexico is more than merely a border guard for the US. It is a huge regional player in its own right and as Brenda Estefan points out, this means that Mexico needs a policy for the region too.

From 2012 to 2018, the administration of Enrique Peña Nieto, through the Mexican Agency for International Development Cooperation (AMEXCID), sought to enhance development in the Northern Triangle by allocating approximately $120.4 million in areas such as road construction and expansion, technical assistance for disaster risk management, national security, water quality monitoring, industrial innovation, and energy efficiency. However, migration from these three countries to Mexico increased by 148% in 2019 compared to 2011. During the same period, the migrant population from Guatemala rose by 59%; from El Salvador, by 136%; and from Honduras, by a staggering 304%. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, AMLO, criticized Peña Nieto’s approach and shifted focus to directly implementing development projects in these countries. In 2019, when former President Donald Trump threatened to impose a 25% tariff on all Mexican imports unless measures were taken to curb migrant flows heading north, AMLO announced plans to internationalize some of his flagship social programs, such as Sembrando Vida. This social assistance program aimed to reduce migration from and reducing poverty in the Northern Triangle by providing support to small-scale agricultural producers. However, the project has yet to yield significant results. According to a multidisciplinary 2023 report, Sembrando Vida’s ambitious goals are still far from being achieved. The report noted that opacity in the program’s implementation undermines efficient monitoring of how Mexican taxpayer money was spent in Central America and found that the funds are not sufficient to assist the number of people expected to benefit. … migration from target countries, like Honduras and El Salvador, hasn’t decreased. The Mexican government has allocated $150 million to Central America through this and other social programs, such as Jóvenes construyendo el futuro, a scholarship that funds youth internships, …However, in January Mexico’s Secretary of Foreign Affairs Alicia Bárcena said that AMEXCID achieved a “paradigm shift,” highlighting cooperation at the state level. “For the first time, social projects are being implemented directly with the target population,” she added. While intentions count, they require proper execution. In October 2023, AMLO convened the Palenque Migration Summit with heads of state from Latin American and Caribbean nations. It concluded with praiseworthy aspirations of ushering in a new era of cooperation and progress to address migration’s root causes. A post-summit joint communique outlined the creation of an action plan for regional development, intraregional trade promotion, and comprehensive migration policies that respect human rights. However, most of this agenda is on hold due, among other reasons, to the electoral context.

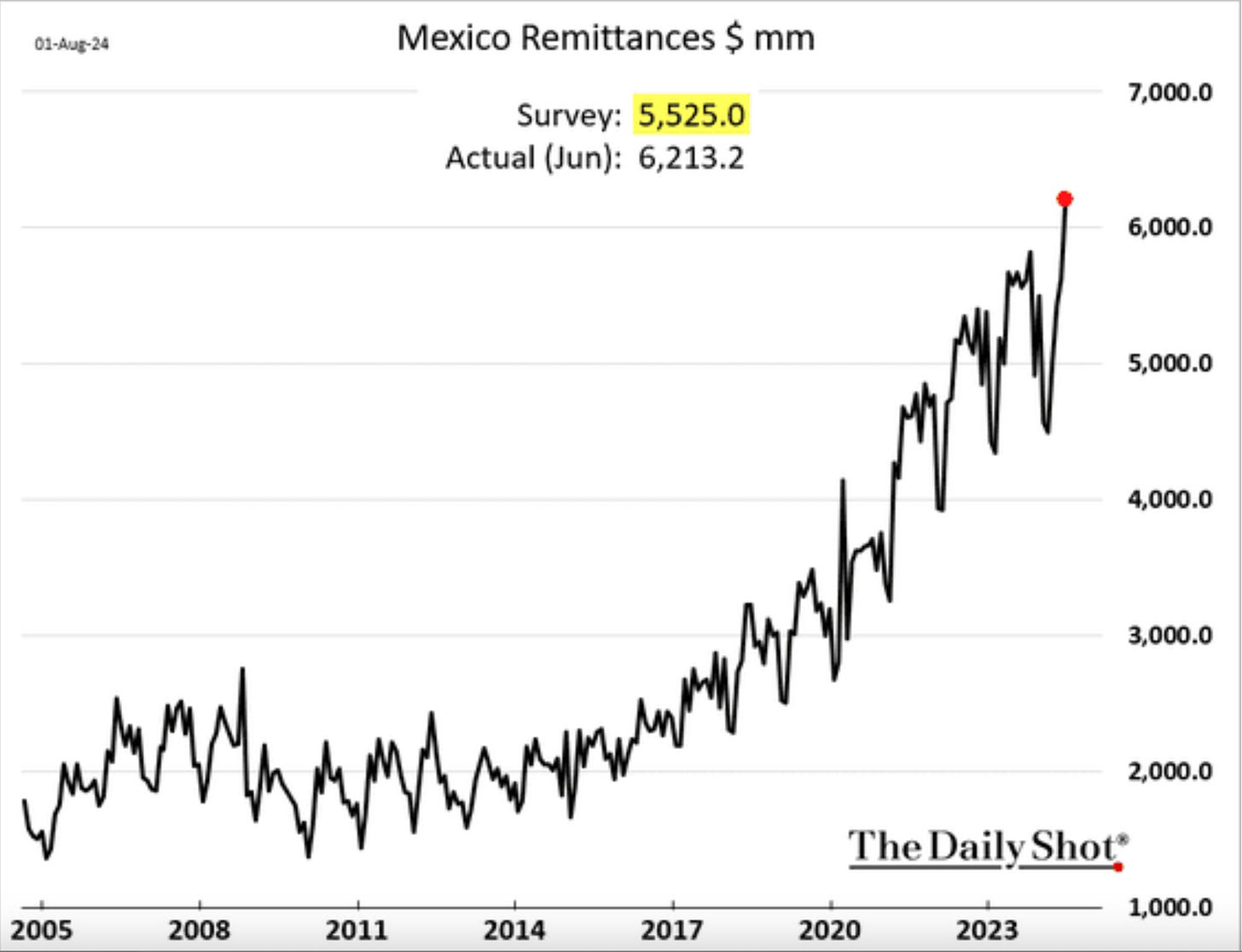

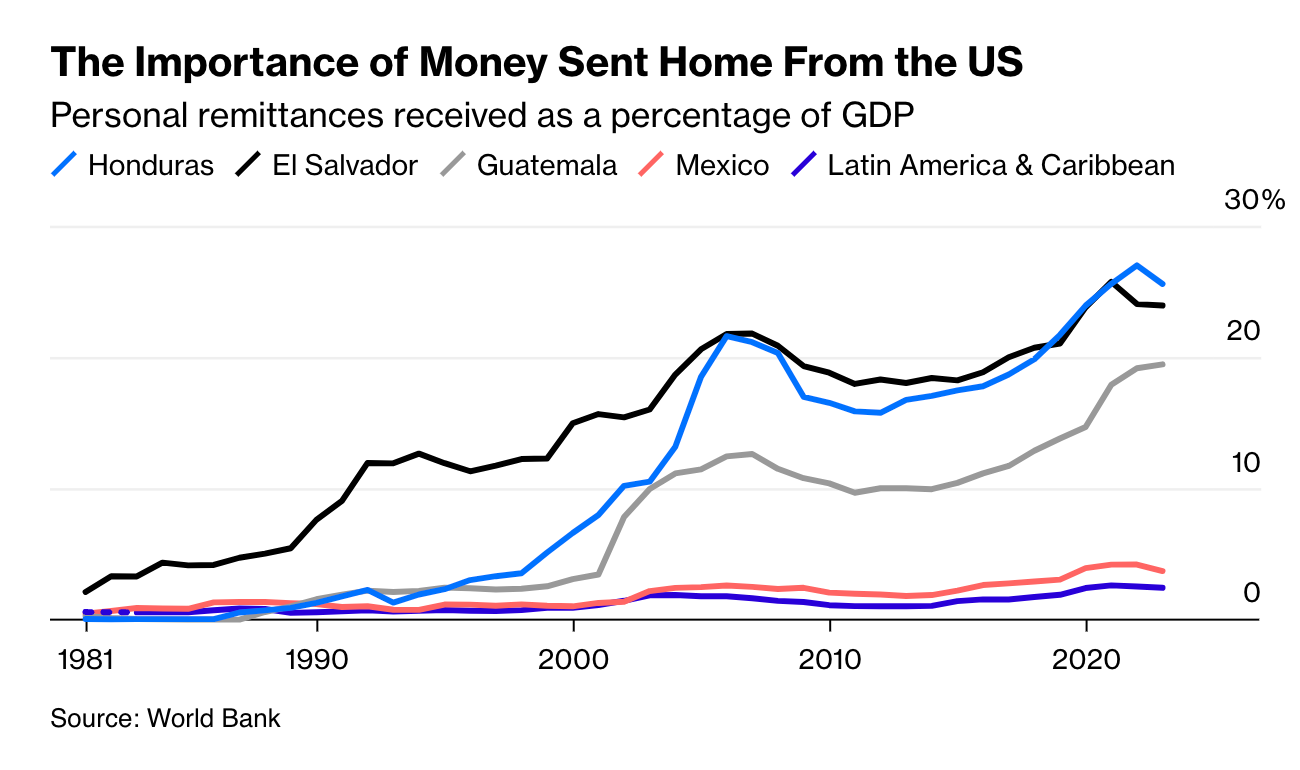

The best hope for something closer to an integrated solution, is that new administrations, headed by Harris and Claudia Scheinbaum might coordinate and jointly fund a regional approach. In the meantime what needs to be taken off the table, on the part of the US in particular, is the gothic rhetoric of panic and disaster. Unauthorized migration to the US is large, but to talk of a crisis is an inflammatory escalation. Right now, migration from Central America and Mexico is actually falling. It has been off-set by rising migration from other parts of the region and the world. Meanwhile, the foreign workforce both authorized and unauthorized are a large and productive part of the US economy. Unauthorized workers make up c. 5 percent of US labour force. And they generate remittances that in many cases transform the lives of their families and communities where they come from. The surge in remittance flows to Mexico is remarkable and surely, along with Mexican economic growth, at the root of the slowdown in Mexican migration.

Over the last decade, remittances from the US to Mexico have tripled.

Mexico has a large, G20 economy. As Justin Fox points out, remittance flows make an even bigger impact on the far smaller and more fragile economies of Central America.

What is needed is not more border controls and militarized policing, but a pooling of governmental resources amongst the stronger players in the region including USA, Mexico the richer Caribbean states and Colombia, not to oppose, but to facilitate, support and invest in the extraordinary human energy, grit and determination that is the counterpart to those remittance flows.

First time I’m reading comments on Mr T’s Substack and I’m shocked by the disrespectful and ignorant tone of so many of them considering the author’s academic, ambitious and serious attempt to tackle big and complex issues facing humanity right now. Guys - if you’ve got nothing constructive to say, say nothing!!

The structural problems of Central and Latin America are created or kept in place by the US. The siege socialism of Cuba or the comprador capitalism propped by the US everywhere else.