Chartbook 306 Nodes, rebar and private equity- How Intel, the weak link in the chip strategy of Bidenomics, is resorting to financial engineering to raise billions for fabs.

Amidst the market focus on AI, Nvidia and the fab 7, and the political cycle which is directing attention towards VP-picks and rallies, I worry that a big story of last week may get swept under the rug: the catastrophic news out of Intel.

Last week Intel, announced 15,000 job cuts, and suspended a dividend that has been in place since 1992. As Bloomberg reported, Wall Street is “losing patience”. “Investors are pulling the kill switch.”

The stock has plunged to levels not seen in a decade.

Why does this matter?

Not because the world is short of the kind of chips that intel is struggling to make. On the contrary, we are just slowly exiting a cyclical glut. If Intel does manage to establish itself as a chip designer and a significant maker of chips (fab operator) that will offer more choice to buyers. But this is not why Intel really matters.

Why Intel matters is geopolitics and the new political economy of industrial policy.

In a world of geoeconomics, decoupling, derisking and disentangling from China, Intel is claiming the role as a national champion. As Susannah Glickman explains in this excellent piece for Phenomenal World Intel has since the late 1960s been at heart of the state-business nexus that defines chip manufacturing and the political economy of high-tech everywhere around the world.

In the last few years under the sign of the new industrial policy, Intel has attracted giant subsidies both from the US, via the CHIPS act, and in Germany. All told, the subsidies committed to Intel around the world, at least on paper, run to more than $20 billion, for one, private company, not in lguarantees, but in hard cash.

Back in 2023 when the industrial policy hype was at its max, I was a sceptic. I did a bunch of TV and other interviews in Germany questioning the logic of Berlin’s public subsidy for Intel. What I was worried about was:

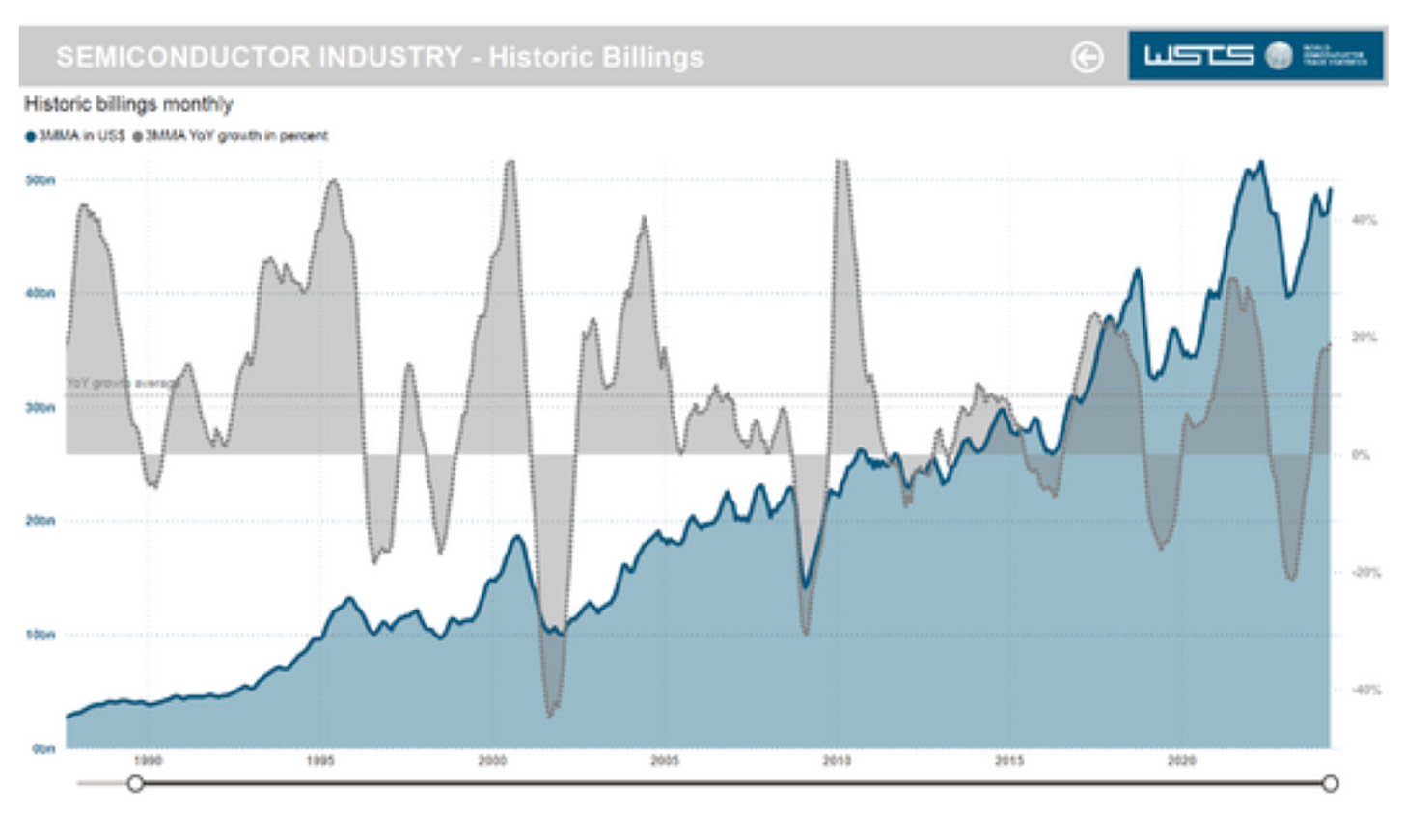

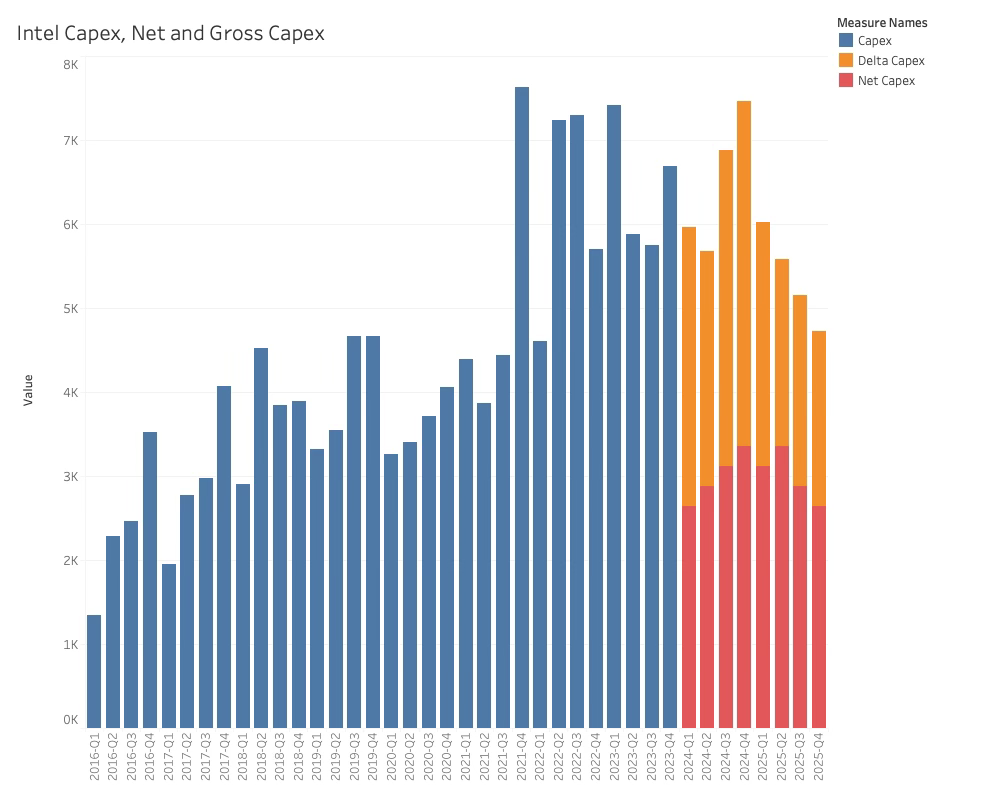

The staggering capital intensity of the industry. This is a sector where private companies will spend over $10 billion per quarter in capex.

Source: Semiconductor Intelligence

In an industry operating on this scale and at this pace, is the public balance sheet big enough to play? I know that sounds like a crazy question, but the CHIPS act allocates .. drumroll … $39 billion in subsidies for creating or expanding U.S.-based semiconductor fabs and an additional $11 billion in research and development. And the money takes many, many months to disburse. In the world of semiconductors that is the spending of one player for one year. For Germany, hobbled by the debt brake, this is very deep water to be playing in.

The semiconductor industry, an ultra high-tech commodity sector with long lead times, is dominated by the vicious swings of a classic commodity cycle (think “hog cycle”). In 2023 policy-makers were harking back to the post-COVID chip shortage, whereas at that very moment we were heading into an industry wide downturn and glut. Again, the industry moves far faster than politics.

Source: WSTS

Furthermore, industrial policy makes most sense at an early stage where it can hope to exercise something like a formative influence, or in industries with many players and plenty of opportunity for benchmarking and competition. The global semi-conductor industry, by contrast, is a vast oligopoly in which the winning and losing hands were already distributed. Taxpayer-funded industrial policy has virtually no chance to creatively reshape the industry. Anyone wanting to play the chip game on a substantial scale has to get in bed with the big players. And amongst those, intel is the big loser.

Intel was once a world leader. It formed a combination with Microsoft and IBM in the 1980s which shaped the early stages of desktop IT. But in the 2000s it missed the boat on chips for cellphones. Then on the fab side it made fundamental missteps in manufacturing. And then it missed the boat on AI. So now it is playing catchup on all fronts. On chip design, as the Economist notes, Intel is miles behind:

This year it expects to sell $500m of its Gaudi ai chips. Nvidia sells $20bn of its ai chips each quarter. What is more, success in the market for ai chips is about more than the chips themselves. Nvidia sells networking gear that ties together hundreds or thousands of its processors. It also has cuda, a software platform, which allows customers to fine-tune the chips.

Finally, more superficially, Intel’s leadership are no doubt highly skilled engineers, but the current CEO is perhaps best described as “weird”. Back in 2022 in seeking to goad Congress into acting faster on the CHIPS act, he remarked about the EU: “This complex 27-member socialist union . . . is now ahead of the US by a solid six months.” Unless this was intended tongue in cheek, and that does not seem like Pat Gelsinger’s style, this is someone who does not understand that he does not understand the people he is dealing with.

Amidst the hoopla of securing the Intel commitment to Germany, I though a fragile coalition in Berlin was underestimating the risks of getting into bed with this firm. I thought the same was probably true for Bidenomics too Washington, but Washington, at least potentially, has resources to play in the big leagues. Intel is an American company. Added to which, Intel was promising to build the “silicon heartland” in Ohio and, you know, when it came to the heartland there was no arguing with the Bidenomics people.

Online in press releases from a few months back, Intel pitches a story of global expansion and its range of partners.

In the US, we are expanding our existing operations in Arizona, New Mexico, and Oregon, and investing in two new leading-edge chip factories in Ohio. We have submitted all four of our major project proposals in Arizona, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oregon to the US Department of Commerce’s CHIPS Program Office. These projects are estimated to represent over $100 billion of US manufacturing and research investments over the next f ive years. In the EU and Israel, we have announced a series of investments spanning our existing operations in Ireland and Israel, as well as a planned investment of more than $33 billion in Germany to build a leading-edge wafer fabrication mega-site. We have also announced our plans to invest up to $4.6 billion in an assembly and test facility in Poland, and the start of high-volume manufacturing using Intel 4 technology and extreme ultraviolet (EUV) technology in Ireland. … Intel teams across the globe are installing new tools, delivering new clean rooms, and completing construction of new buildings. To give an idea of the sheer scale of operations, in 2023, about 145,000 tons of steel—roughly the weight of 20,743 African elephants—was used in our construction and expansion projects, Our construction teams also poured over 2 million cubic yards of concrete—enough to build the Empire State Building 32 times over.

Source: Intel

But, all this talk about factories and machinery and steel and concrete, cannot hide the fact that twelve months on from the German announcement and two years on from the CHIPS act, in terms of actually mass-producing ultra high-end chips that are competitive at the global level and able to generate profit, Intel is way behind its competitors and the gap will not close anytime soon.

CEO Gelsinger tells a story to analysts of building two world-class companies: the Fab side and the product-development side. The product designer will be able to choose not just intel production facilities, but fabs anywhere in the world. The fabs will make not just intel chips, but will be open for business from all comers, which makes them particularly attractive from a US strategy point of view.

But as one Timothy Prickett Morgan remarks, this may be a good patter but, “that is a lot calmer than the situation really is. This is going to be hard to watch over the next couple of years, and even harder to do.”.

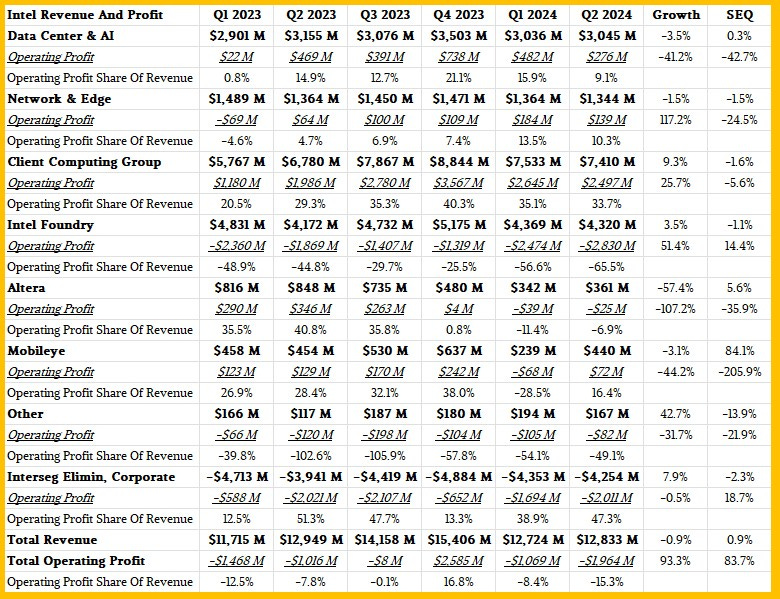

The results that caused the stock value to crash tell the story.

In the second quarter, Intel had $12.83 billion in revenues, down nine-tenths of a point, and posted an operating loss of $1.96 billion, almost twice that from the year ago period and from the first quarter of 2021. Because it has subsidiaries and so many intersegment eliminations, we are only getting an operating income from Intel these days, not a net income. Intel exited the quarter with $11.3 billion in cash and just a tad under $18 billion in short term investments. Which is enough capital for maybe one and a half fabs these days. In other words, not much if you are trying to be the world’s second largest foundry and compete against TSMC.

As Richard Waters of the FT asked back in April, after the previous set of terrible results:

has Washington just committed to pouring tens of billions of dollars into a flailing has-been in a vain attempt to claw back a lead in global chip manufacturing? The enormity of the bet that the US is making was laid bare this week, as Intel revealed just how big a hole the manufacturing side of its business is in. Had it not been for a change to its depreciation policies, the company would have reported a staggering loss of $11.2bn from manufacturing last year on sales of $18.9bn. Even after extending the life of some of its manufacturing equipment from five to eight years, it was still left with nearly $7bn of red ink.

Come the summer crunch and Intel has had to make tough decision. On top of slashing 15,000 jobs and halting dividend it has also committed to reducing its capital expenditure. As Claus Aasholm notes in the Semiconductor Business Intelligence Newsletter:

In the conference call, Intel revealed that the CapEx budget would be cut by 20% in 2024 to $26B in 2024 and $21.5B in 2025. The new budget was presented interestingly as a Gross and Net CapEx budget.

As Intel’s profitability started the dance around the zero line beginning in 2022, the company was unable to finance the CapEx budget of the IDM 2.0 strategy through retained earnings and had to find alternate ways of funding the plan. Banks would want a premium interest rate because of Intel's risky situation, and diluting the stock would make the comeback more difficult. It was time to get creative.

One option was to rake in the subsidies. Gelsinger has taken to various media platforms to sell his firm as a national champion and managed to tap a total of $20 billion under the Chips act in direct grants and loans. But since public money is no longer enough, Intel has “blended” it with an increasingly wide range of private finance. Earlier in the year, Intel was rumored to be “in discussions with … private capital groups — KKR and Stonepeak — over talks to finance its new semiconductor plant in Ireland before entering exclusive talks with Apollo”. In the end it settled for a deal with Apollo in Ireland.

Brookfield Asset Management are investing in its Arizona fabs. This is how the FT summarized the deals that are badged as the Semiconductor Co-Investment Program:

In 2022, it sold a stake of up to 49 per cent in a chipmaking plant it is building in Arizona to Canada’s Brookfield Infrastructure Partners for $15bn in order to finance the $30bn project. Apollo has emerged as a large lender for investment-grade rated loans that are more complex than corporate bonds sold to the broader debt markets. Last year, Apollo structured large investment-grade rated loans to companies including Air France/KLM and German property developer Vonovia, and has signalled it is rapidly expanding its capacity for similar arrangements. This month, Apollo told its shareholders it expected to originate over $200bn in debt annually in coming years, fuelled by lending to investment-grade rated companies such as Intel. Apollo has told shareholders that its lending will focus on the construction of new infrastructure such as digital communications networks, data centres, renewable energy facilities and semiconductors. Apollo’s lending is being supported by its insurance business, with more than $500bn in assets, which generally can own these debts to maturity. Ireland’s government, which relies heavily on corporation tax revenues from global tech and pharma companies, had no immediate comment on the talks. Intel has invested more than $34bn since 1989 to transform a former stud farm in Leixlip, Co Kildare, into a chip fabrication plant and expand operations in Ireland.

Given the reputation of a player like Apollo, one can only hope that intel’s corporate lawyers, who are in charge of what they are calling a “smart capital” strategy, are more competitive in relative terms than its chip designers. Intel is still an A-rated company. It could therefore,

“ … sell bonds or stock to fund the capital buildout. Instead, the 51/49 joint venture (with Apollo) targets a cost of capital owed to the Apollo group that lies between Intel’s debt and equity charges. … Apollo and its co-investors have created a highly structured investment where its returns should achieve at least the high single digits with little risk of falling short. For Intel, it minimises its near-term cash obligations at a time when its profitability has been challenged. … An $11bn commitment might pale in size with the market value of Nvidia. But only a handful of companies like Apollo and Brookfield are able to benefit from deals such as the Intel joint ventures where multibillion-dollar cheques are merely table stakes. While the masters of the universe will probably do just fine thanks to the fine-print details they have negotiated, Intel shareholders should ask if growing chip manufacturing and production can be done efficiently enough to generate a positive return on their common equity. Intel has shown the ability to be creative in financial engineering. But its shares today are down slightly from when the original Brookfield deal was announced in 2022.”

For all the emphasis in Intel’s media on steel and concrete, none of that old school engineering would have been possible without this exercise in financial engineering. As one glowing review puts it: “These deals, combined with the Chips Act funding and other subsidies, are a complete master stroke for which Intel and Pat Gelsinger have not received sufficient credit. In a situation where Intel lacked funding, and it would be expensive to borrow, the SCIP rabbit was pulled out of the hat: For an investment of approximately 1/3rd of the total needed for the two fabs, Intel got 51% ownership and 100% control.”

Certainly what is not working, so far, is the strategy of separating out the two wings of the business. Again Richard Waters is in cutting form:

… the thumbs down from the stock market is an ominous sign. Splitting out the financial performance of its manufacturing arm, as Intel has done, was meant to be an important milestone. It was supposed to give Wall Street confidence that its manufacturing and chip design businesses are now being run independently, increasing the pressure on each to perform. It was also meant to act as the catalyst for a stock price rebound. Chief financial officer David Zinsner suggested that, within a couple of years, the manufacturing business alone should be worth at least $200bn — more than the whole of Intel today. That the ploy hasn’t worked is down to one simple fact. As far as most investors are concerned, the two sides of Intel’s business are still joined at the hip, and their codependence will continue to dictate its fortunes. … Newer process nodes require ever-larger investment, which means ever-larger production volumes to make them economically viable. The US is backing Intel because it sees the company’s new foundry business — making chips on behalf of other companies, not just to Intel’s own designs — as an important national asset. But the long product cycles in the chip industry mean it will take years to bring in new customers, leaving Intel’s manufacturing business dependent on its own chip design arm as anchor customer. On this score, things are not going well. After completely missing the mobile revolution, Intel is now struggling to come up with the right products for the booming AI market. … For investors, the turnaround continues to stretch out further into the future, with little prospect of anything on the horizon to help the stock. For politicians in Washington, meanwhile, the costs of industry policy in the semiconductor industry should be starting to become clear. They were already facing the need to come up with more financial backing for Intel, just to keep pace with the subsidies the company’s rivals enjoy. If the company faces chronic low profitability and struggles to reach full capacity at its new plants, it will only add to the pressure. Backing Intel to become the US chip manufacturing champion may have been the right move from a national and economic security perspective, but future administrations in Washington will learn the full costs of that decision.

So what is the upshot? A once leading US tech company, that lost its competitive edge over a period of decades, is leveraging the need for national champions under the flag of Bidenomics and the profit-seeking of private capital, to mobilize a gigantic $100 billion investment drive, in the desperate hope that it can cross the yawning competitive and technological gap and emerge as a profitable competitor - not a Nvidia, but at least a viable player. Even that will be a gamble at long odds.

In the wake of the most recent set of bad news, the CEO, who is by all accounts a devout Christian, took to quoting scripture on twitter.

In the America of today, should we even be surprised?

You're right about Intel, but the Chips Act also funded projects in the US by other well run Chip manufacturers:

The companies that benefited from the CHIPS Act

Company Amount Factory locations

Intel $8.5 billion Arizona, New Mexico, Oregon, Ohio

TSMC $6.6 billion Arizona

Samsung $6.4 billion Texas

Micron $6.14 billion New York

Global Foundries $1.5 billion New York, Vermont

Microchip Technology $162 million Colorado, Oregon

Polar Semiconductor $120 million Minnesota

BAE Systems $35 million New Ham

So your general attack on Bidenomics is a little overblown. The Chips Act has helped create more high tech h Chip manufacturing in the US which even if by foreign companies is still a strategic and economic benefit to Americans.

I know squat about economics but I do appreciate your reports and make an effort to better understand how economies work, albeit at a below layperson's comprehension. I read this twice, and lacking further understanding, I too caught the whiff of criticizing bidenomics, the policies of which seem to be to be nothing but well intentioned. Have any Republicans presidents made such efforts to ramp up manufacturing of anything except fossil fuels in comparison to the intentional efforts as recent Democrats have? I would love a larger comparison/analysis. Thank you.