Chartbook 303: The climate stakes in the 2024 US election. Is recarbonization in America's future? How much difference might Trump-Vance make?

From the point of view of the climate crisis, how much is at stake in America’s election in November? How much difference does the choice between Trump and Harris make to the path of American emissions?

At a time like this, even the putting the question in these terms can seem frivolous. Do we really need to have this question quantified? A second Trump Presidency would clearly be a disaster for the climate cause, both in the USA and far beyond.

The Biden-Harris administration was the most successful administration in US history in passing climate legislation. It was, on certain issues at least, proactive in global climate talks as well. By contrast, Trump would try to rollback climate measures, empower fossil fuel interests and spout climate skepticism. When he remembers, he would presumably withdraw from the Paris accords again. This would empower anti climate action around the world. Trump at the Republican National Convention promised to boost oil production to “levels that nobody’s ever seen before”, making America so “energy dominant” that it “will supply the rest of the world”.

The answer with regard to emissions is, therefore, surely obvious. The impact on emissions will be terrible. Do we really need to know how much worse? Is asking this question really just a dig at the heroic legacy of Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), “the most significant climate legislation in the history of the world”, as the President claimed in his letter announcing his withdrawal from the race?

Though uncomfortable, if we want to position ourselves with any degree of precision in the current moment, this is the kind of resistance that we ought to push through.

Sure Trump 2.0 would be terrible. But how terrible? How do we figure that out?

It isn’t an easy question to answer because there is so little experience of serious climate legislation in the USA and because the IRA was passed by a wafer fin, capricious Senate majority as recently as the summer of 2022 and so it has had less than two years to show its effects. A full repeal (an unlikely scenario) would take effect before the IRA had really had the chance to do its job.

Furthermore, evaluating policy in real time involves guesses about the future. This is particularly true for climate policy where the critical questions are about 2030 and 2050. So this seemingly simple, technical question - how much difference would a Trump Presidency make in quantitative terms? - exposes the fact that our understanding of the world hinges on disciplined conjecture based on concepts and assumptions combined with forward projection of quantified past experience i.e. on models.

This is an unsettling, but important thing to acknowledge.

In those models, a large range of factors other than policy impact on the trajectory of CO2 emissions. Having a good or a bad President makes a difference, but it is only one factor in a complex mix. The price of oil, the price of renewable energy capacity and batteries, the cost of capital, the rate of overall economic growth, they all matter. Indeed, since Bidenomics is not the “big green state” that some dream of, but instead a set of tax incentives and credit facilities those market forces are, in any case, the primary drivers. It is through prices and costs that Bidenomics works.

The models thus serve to put politics in its place. Particularly, in a high-stakes election year, that is why the question can feel so irksome. At a moment when democracy is at stake even asking the question - how much does policy matter? - can seem foolish or worse. It invites the retort: “Don’t you understand! This is about more than battery prices.”

Suffice to say, the aim of the game here is the opposite. The aim is to understand how much politics matters, what its limits are and to gauge the other historical forces that are at work. This may help us to weigh the question - and in the case of the United State right now I take it to be an open question - how we might imagine a world in which democratic politics might actually matter more than it currently does.

Once you start considering the array of forces involved in deciding how much is invested and how much energy is consumed you are reminded that those forces are not distinct from the political process. It is not just that they will continue to act on investment choices regardless of who is in the White House or has the majorities in Congress. In a political economy like that in the USA, those forces actually shape policy - by framing the public debate, in drafting legislation, in forming majorities and in its implementation.

The political process is not exogenous to American society or the American economy. And national elections, voting, fund raising etc are only one way in which American society interacts with its political system. So the reason that America finally got climate legislation in 2022 in the form of the IRA, was not simply that “good President Biden” was in the White House, but that the overall balance of interests and opinion within the American socio-political system had shifted. This too was finely balanced. But in 2022 it was decisive and that “bloc” will likely outlast the Biden Presidency. In addition, in the USA policy is made at both national and state level. In huge states like California, with an economy larger than that of Italy, climate policy will continue regardless of who calls the shots in Washington.

Of course, the very smart people who made the Inflation Reduction Act knew all this. The legislation was not some sovereign gift from above, but endlessly worked and reworked to incorporate a huge coalition of interests. Four-fifths of the benefits of Bidenomics go to Republican congressional districts. Unless there is a political earthquake in November, even if the Democrats lose the White House and Congress, large parts of that coalition will remain intact and influential. To give one example reported by The Economist, “Dan Brouillette, who served as energy secretary under Mr Trump and now heads the Edison Electric Institute, an association for America’s private-sector power utilities, has vowed to defend the ira.”

So, after this long-winded preamble, what is the answer to our question? How much difference should we expect in the event of a Trump-Vance victory?

Since this involves modeling we have a range to choose from. The three analyses that have crossed my radar are:

“Hitting the brakes: how the energy transition could decelerate in the US." An issue brief by private energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, discussed in The Economist.

A typically comprehensive report by climate think tank Carbon Brief, which pulls together the results from several different energy modeling teams to work

The official analysis of the US Energy Information Agency, whose energy outlook for 2023 contains a scenario analysis that bears heavily on possible future beyond 2024.

The upshot, for those who are holding their breath, is that YES a Trump victory would be horrible for the trajectory of US emissions. It would not end decarbonization. But it would mean that emissions are substantially higher than currently forecast.

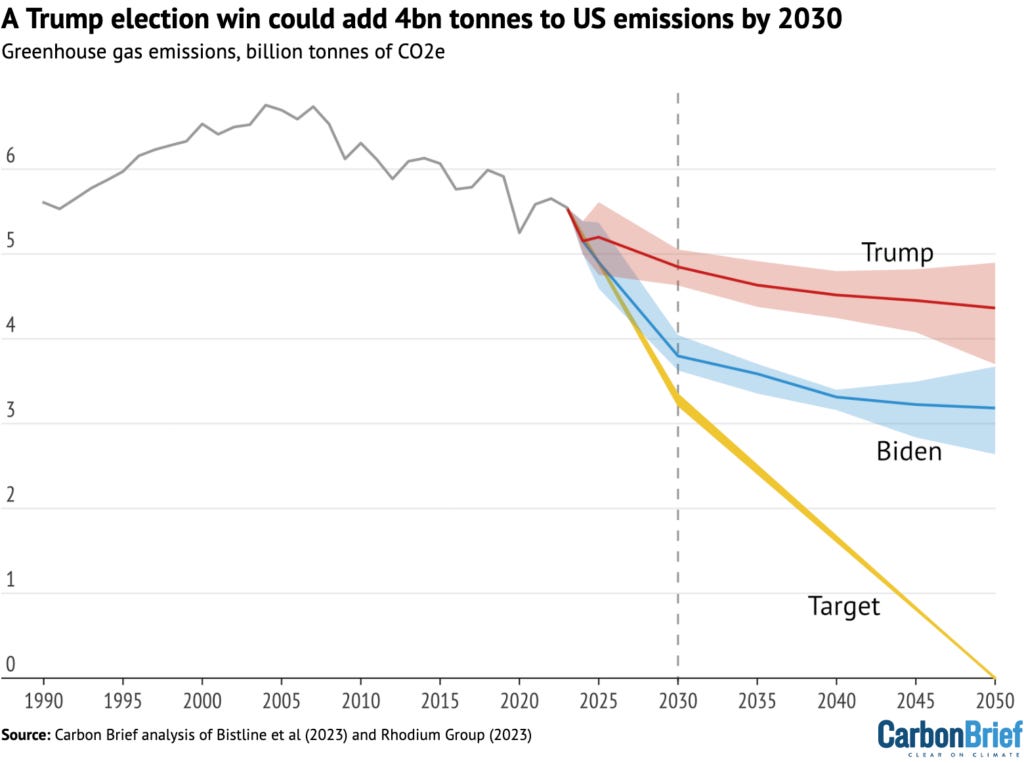

Carbon Brief puts the case in the most dramatic terms:

A victory for Donald Trump in November’s presidential election could lead to an additional 4bn tonnes of US emissions by 2030 compared with Joe Biden’s plans, … This extra 4bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) by 2030 would cause global climate damages worth more than $900bn, based on the latest US government valuations.

For context, 4GtCO2e is equivalent to the combined annual emissions of the EU and Japan, or the combined annual total of the world’s 140 lowest-emitting countries.

Put another way, the extra 4GtCO2e from a second Trump term would negate – twice over – all of the savings from deploying wind, solar and other clean technologies around the world over the past five years.

If Trump secures a second term, the US would also very likely miss its global climate pledge by a wide margin, with emissions only falling to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030. The US’s current target under the Paris Agreement is to achieve a 50-52% reduction by 2030.

Carbon Brief’s analysis is based on an aggregation of modelling by various US research groups.

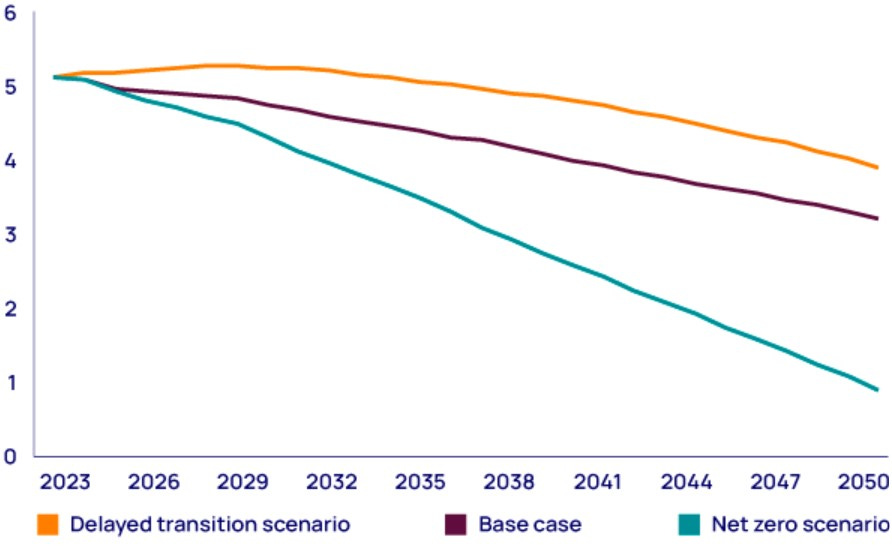

Wood MacKenzie do not disagree, but puts the contrast in rather less dramatic terms. The yellow line is the Trump trajectory. The maroon line is the trajectory if Biden’s policies are continued.

US net energy-related CO2 emissions by outlook, in billions of tonnes

The difference between the Trump and Biden-Harris paths is somewhat smaller in the Wood MacKenzie projection than in the estimate by Carbon Brief. Wood MacKenzie are less optimistic about Biden’s policies than the very bullish Carbon Brief estimates. But, if anything, Wood MacKenzie are even more pessimistic about the trajectory under Trump.

Wood MacKenzie break down the possibleTrump effect as follows:

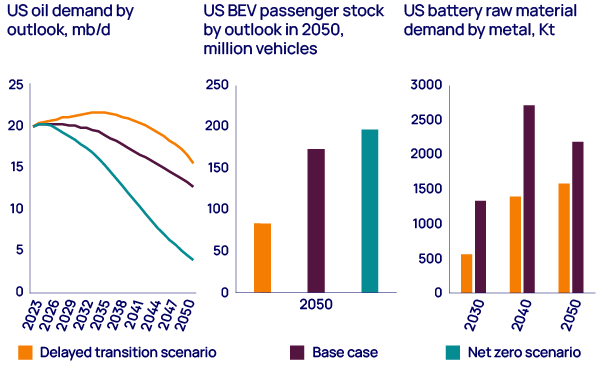

EV sales stumble: Rather than full EVs, American households continue to opt, as they currently are, for hybrids. “Weakening federal greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and fuel economy regulations continue this trend, and the total stock of EVs by 2050 would be 50% lower than in Wood Mackenzie’s base case.”

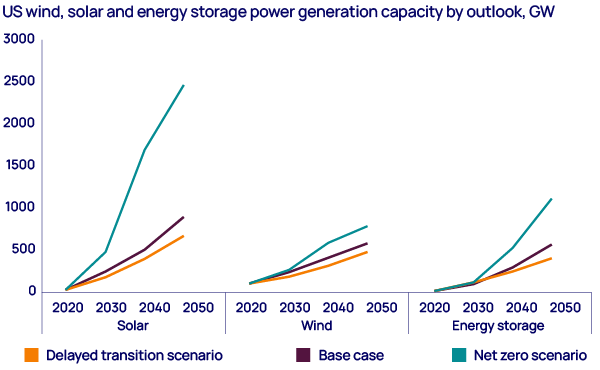

Zero carbon power supply faces strong headwinds: “With less financial support from the Department of Energy Loan Program Office, fewer grid improvements. … wind and solar and energy storage capacity would be about 500 gigawatts (GW) by 2050, 25% lower than the base case.”

Coal would remain in the mix for longer. :In the delayed energy transition scenario, the pace of electrification would ease in the near term. However, industrial, residential, electrolytic hydrogen and EV usage would still combine to increase power demand by 2.0 petawatt-hours (PWh), a 45% jump from 2030 to 2050. With less policy support for renewables and continued load growth, there would be no way out of using coal. As a result, by 2040, coal generation capacity would be four times higher than the base case, with 104 GW on the system.”

Low-carbon hydrogen could falter. “The lack of federal demand-side targets, reductions in federal funding and cost inflation would challenge the investment case for low-carbon hydrogen.” “The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Energy (DOE) and Treasury Department would promulgate new regulations that would favour fossil fuels. For example, the 45V production tax credit could favour blue hydrogen over green hydrogen.” “Near-term growth shifts to export markets in Europe and Asia”.

From the point of view of decarbonization these are all significant setbacks. But they serve to modify rather than to reverse a trend. What defeats Trump’s recarbonization agenda is not just the robustness of the Biden-era legislation, but the fact that decarbonization is being driven by so many other factors, above all the relative price of solar, wind, battery storage v. gas and oil.

As The Economist reports, green energy has momentum in the USA regardless of the election:

“Big commercial customers, such as the tech giants, which need ever growing amounts of power for their data centres, have made public commitments to cut their net emissions to zero. NextEra Energy, a Florida-based utility that is one of the world’s biggest developers of clean energy, is committed to investing roughly $100bn in solar, wind, batteries and transmission by 2027 regardless of who wins the White House.”

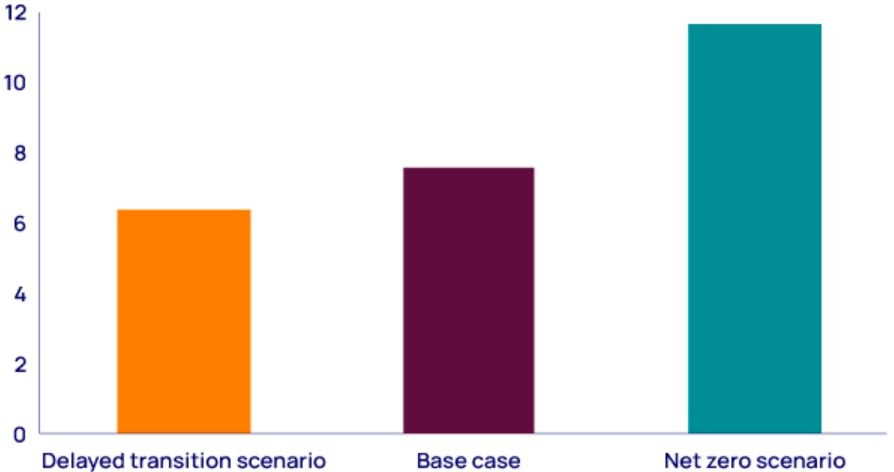

So, what is at stake in this election is the choice between more or less gradual decarbonization paths. I say that advisedly, because what all of the modeling also shows is that no policy on offer in the 2024 election puts the United States anywhere near a path to full decarbonization by 2050. The figures for investment summarize this in stark terms.

US capital investment in the energy sector, cumulative, 2023-2050, in US$ trillion

Source: Wood Mackenzie. Total capital investment for the US includes upstream oil and gas, power generation, power grid and EV infrastructure, hydrogen and CCUS. US$11.8 trillion dollars in capital investment in US energy is required on a cumulative basis from 2023-2050 to reach our net zero scenario. Investment is 55% lower in our delayed transition scenario.

Over the horizon to 2050 Wood Mackenzie estimates that there would be a $1 trillion difference in (mainly clean) energy investment between a Trump-trajectory ($6.5 trillion) and a scenario in which IRA remains in place ($7.5 trillion) But that is a small fraction of what would be required to be on course for net zero (closer to $12 trillion).

In other words, the most progressive climate policy in American history has nudged the USA only a small step away from the path under a crude policy of climate denial. Bidenomics has taken us only a small step towards sanity.

Of course, 2050 is a long way off, so you might say that 2030 is the relevant date. On the prospects for 2030 the models differ. The models consulted by Carbon Brief are far more optimistic than the Wood MacKenzie model. But further out there is no fundamental difference. No policy so far implemented or discussed in the US gets us close. That matters because though 2050 is “far off” energy systems are long-lived assets.

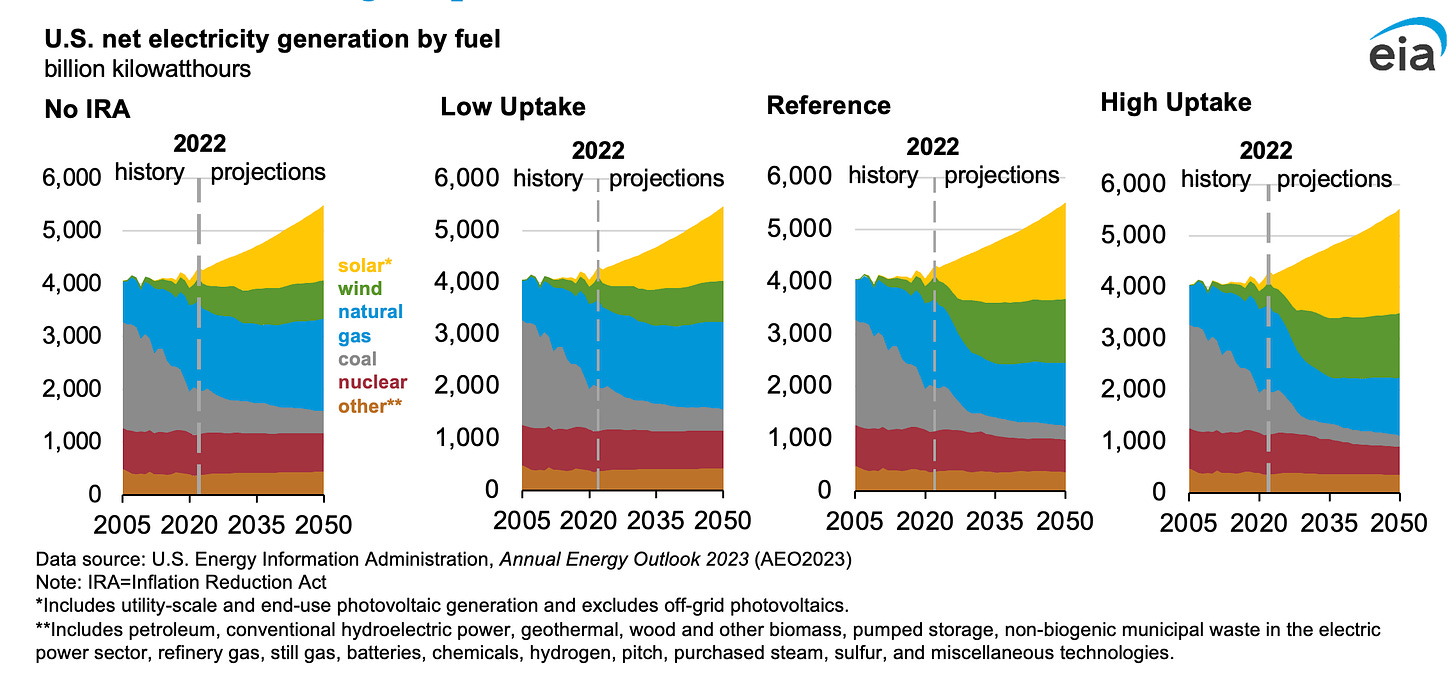

The EIA outlook offers an interesting array of scenarios for electricity generation, which is the bit of the economic system that is both critical for decarbonization - we have electrify everything - and, relatively speaking, easiest to decarbonize - wind, solar, batteries, hydro & nuclear are the solution.

Since as Wood MacKenzie points out

A second Trump administration would likely slow down funding for a trio of initiatives: the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Program, Home Energy Rebate Programs and the Clean School Bus Program. However, electrification is a structural trend; industrial, residential, electrolytic hydrogen and EV usage would still combine to increase power demand by about 2 petawatt-hours (PWh), or 45%, over the period from 2030 to 2050.

On any scenario, with or without Trump, solar is the lowest cost technology to meet that increase in power demand. The question, on the current range of policies, is how much gas is displaced by wind power. Coal is declining in any case. Nuclear is not going to have a spectacular revival by 2050.

But, as this modeling too shows, none of the current policies under consideration get the United States to net zero. Though the rate of renewable investment has speeded up since 2020, as Wood MacKenzie’s scenarios spell out, a net zero path would see solar booming at Chinese rates, rather than those we see in the USA today.

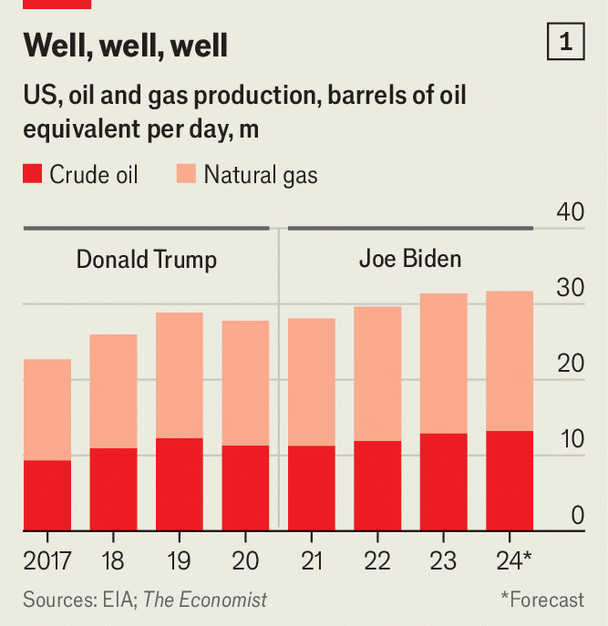

And electricity is the low hanging fruit with coal-fired generation as the easy victim. The real heart of the US fossil fuel complex, unlike in China, is not coal but hydrocarbons, i.e. oil and gas. On this score the record is stark. Far from decarbonizing, since the 2010s the USA under the Trump and Biden administrations has produced more oil than any country before, ever. The fracking boom has transformed not just the American but the global oil and gas equation. This has been driven by supportive policies, plus technological innovation and, for a long time, very cheap capital. The United States is also by a large margin the world’s largest natural gas producer, leading Russia the #2 by 40%.

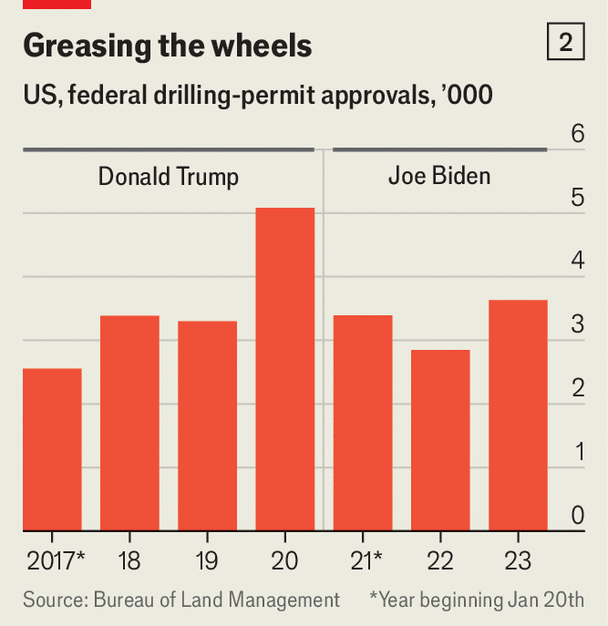

Despite the bias amongst oil interests towards the GOP and despite grumbling about regulation and licensing, the Biden administration did nothing to even broach the issue of the run down in oil and gas production that is essential if the US is ever to achieve net zero. The Biden administration has issued federal drilling permits at a rate no different than Trump in his first three years and has pushed US gas supplies as a strategic asset to the US-led coalition against Russia and China.

As one plain-speaking oil consultant admitted to the Economist, “no federal policy meaningfully restrains near-term production” of oil or natural gas in the USA, whether under the Biden administration or Trump. What we have seen to date is shadow-boxing. We dont know what the politics of an administration determined to curb oil and gas exploitation in the USA looks like. When oil prices have twitched upwards the Biden team has sought to massage them down again.

As Wood MacKenzie’s modeling shows, a Trump administration would favor a shift from internal combustion engine vehicles to hybrids rather than battery powered EVs, but whether on the IRA-continuity or the Trump path, demand for oil barely declines in the United States before the mid 2030s.

The message is clear. As far as climate policy is concerned why this election matters so much is not the defense of Bidenomics, though that matters. The election matters because the Democratic Party coalition is the only one in US politics that offers any prospects of continuing to push policy beyond its current limited scope. From that point of view what is telling, so far at least, is how little climate has featured in the election, other than in attacks from the Republican side. Though Harris is rumored to have greener instincts than Biden - back in 2019 she voiced some support for a ban on fracking - she has made no new commitments. The Democrats presumably think that in the aftermath of the price shock of 2021-2023 climate is not a winning issue and that large numbers of Americans continue to regard the energy transition as an expensive liberal fantasy that threatens their way of life, rather than as the promise of a much less bad world that is within the grasp of a rich country like the United States.

The Biden administration’s policies helped to accelerate global decarbonization trends in the USA and to loosen national constraints. It has neither shaped a new technological paradigm nor decisively shifted the balance of America’s political economy. If this is to happen it will be the work of years to come. Continuing to push that argument is what a Harris administration would give America the chance to do. We have a very, very long way to go.

Greenhouse gasses are not contained within the US border. I didn’t see anything in here that indicated global CO2 emission would grow based on increases in US fossil fuel production. Given the inelasticity of demand for oil and gas one could argue that greater US production which is generally cleaner would actually reduce net global emissions by displacing coal or tar sand production. US net zero in itself means nothing.

I imagine it's challenging to get vast swathes of the US electorate engaged in this issue over the very real economic pain that the Uniparty has inflicted upon them for 40 years now. Neoliberalism's chickens are coming home to roost ...