Chartbook 299 "Shit life syndrome", Starmer's Labour Party & the UK election: democracy under conditions of deconvergence.

“Shit life syndrome”, as Sarah O’Connor informed us in her prize-winning FT report on the depressed English seaside resort of Blackpool (2017), is a folk diagnosis amongst doctors in the UK National Health Service that describes

mental or physical health problems …. the causes are a tangled mix of economic, social and emotional problems that they (the doctors) — with 10- to 15-minute slots per patient — feel powerless to fix. The relationship between economics and health is blurry, complex and politically fraught. But it is too important to ignore.

In the podcast last week, Cameron Abadi and I discussed the UK election.

Obviously, you can’t but be delighted to see the back of the tories. But Cam asked me two questions that set me thinking. Is Keir Starmer analogous to a centrist like Macron? Is Starmer a British version of Scholz? Clearly, the answer to both question is no. That seems to me to be significant. Not that British and European politics have ever been all that similar. Political traditions and electoral systems are different. But the degree of divergence in the current moment is telling.

Starmer’s Labour party and his government are defined by Britain’s peculiar national problems that are related to, but are increasingly distinct from and articulated in an idiom divergent from that of Britain’s European neighbors. Starmer’s government is, to that extent an expression of what in an earlier newsletter, I called Britain’s deconvergence. As much as they seek to overcome the malaise of “shit life syndrome”, they articulate an insular and “blocked” reaction to it.

To bring that story of economic divergence up to date, we can draw on a dossier on the UK’s miserable economic performance, compiled by the research department of Unicredit.

In terms of dollars per hour, the UK’s labour productivity has settled at the bottom of the G7, in uncomfortable proximity to Italy.

Chronic underinvestment is a key determinant of this miserable track record.

The result is a historically unprecedented stagnation of real weekly earnings for a large part of the British population.

Source: Unicredit

Brexit has no doubt contributed to this. But the deterioration started in 2008 under Labour, with the heavy blow suffered by the City of London. Tory policy made things worse. After the disastrous final years of Tory rule, it is little wonder that the OECD records that only slightly more than a quarter of the UK population showing any trust in their national government. This is below France or Italy.

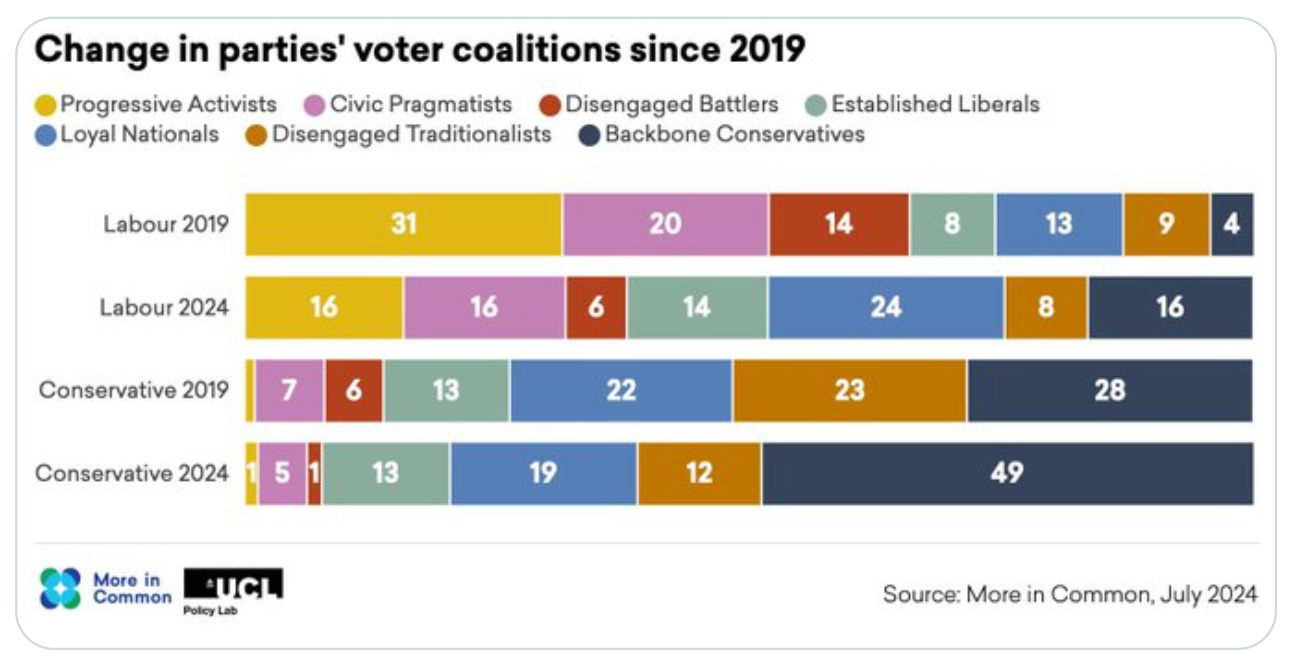

If there is one theme in the current election it is the resounding desire for change. This is one of the most clear cut results of the polling by More in Common and the UCL Policy Lab. Across every type of UK voter, whether progressive or conservative, there was a desire for a fresh start.

This matters because in Britain’s first past the post system, unless there is the kind of Popular Front arrangement we saw in France, it is up to voters to organize themselves to kick the incumbent party out. This is what they did in magnificent style and that is what explains the startling ability of the Labour party to achieve a huge parliamentary majority with such a modest share of the vote. Starmer’s reshaping of the party may have enabled that, allowing some tactical switching. But the key thing is the coherence of the anti-Tory vote and the divisions within the conservative ranks.

The huge majority makes the situation of Starmer’s government quite different from that of Scholz’s three-party coalition, let alone France’s complicated situation. But the differences go deeper than that.

Quite unlike Scholz’s SPD, which is a party of social democratic pensioners, the anti-Tory vote in the UK is of young and middle-aged people. Imagine the SPD, Greens and parts of the liberal FDP merged together.

Source: YouGov

Like in France, education tends to bias towards Labour, Green and Liberal voting. But there is far less class bias in the Labour coalition, as measured by employment or other sociological markers, than in its French analogues. What we did not see in the UK in the 2024 election was the kind of inversion of class alignment that we have seen in France and Germany, with working-class voters opting strongly for right-wing and far-right parties. Though his coalition is far broader than that and though industrial workers make up a small fraction of the UK population, Starmer’s own emphasis has been on the fact that his father was a skilled manual worker.

In a dramatic and welcome reverse of Tory practice, Starmer’s cabinet may come from a variety of class backgrounds but its members were overwhelmingly educated in state schools.

The More in Common/UCL data allow us to dig deeper into the Starmerite coalition and to reveal more about where it sits in the UK’s increasingly distinctive political culture. One of the striking features of Starmer’s leadership, very much in contrast to Corbyn or for that matter Scholz in Germany, is his relentless insistence on patriotism. And, in its own terms, it seems to have worked. Starmer’s vision of “Little Britain” has attracted the voters he asked for.

In the 2024 election, the data from More in Common/UCL identify “Loyal Nationalists” as the largest single group of Labour voters. This group is defined as follows:

“ Loyal Nationals: A group that is anxious about the threats facing Britain and facing themselves. They are proud, patriotic, tribal, protective, threatened, aggrieved, and frustrated about the gap between the haves and the have-nots.”

How will Starmer and his party govern? What matters to the UK electorate at this point? A progressive realist foreign policy? Climate? Europe? Economic growth? Technological dynamism? None of those. What matters are bringing down National Health Service waiting times, reducing the cost of living and restricting immigration.

It is an inward-turned, nationally focused set of preoccupations that precisely reflects the beating that British society and key public institutions have suffered in the last 15 years. Unlike the “reform” coalition that once voted in droves for Macron, or Scholz’s elderly devotees of Germany’s social market economy, British voters want something akin to a restoration: Govern with a modicum of decency and make life less shit for Brits.

There are constituencies in the UK with other concerns, as is visible in any British city, where Palestinian flags signal that Israel’s on-going massacre in Gaza is a major issue for millions of people. But rather than responding to that remarkable mass movement, Starmerites have wielded alignment with Israel as a weapon against the Corbyn-era left-wing of the party. Excluded by Labour, independent candidates, includingCorbyn himself, ran and won in several constituencies. Across the country, in constituencies with a large Muslim population there was a pronounced fall in the Labour vote.

To the Starmerites, whether or not their personal politics are Zionist, this is a price worth paying to endear themselves to the “patriotic center” that is allergic to slurs of anti-semitism and would like to see further, presumptively Muslim, immigration restricted. The party leadership know that in most constituencies their progressive voters have nowhere else to go.

The same logic applies to the European issue. At the time of the referendum, there was overwhelming support amongst Labour’s core constituency of younger, better educated, working people for Remain. But reopening the Brexit question has been ruled out by the Starmerite leadership.

Labour will offer more decent and competent government than the Tories. That shouldn’t be hard. But the key message of the campaign - before we even get to Labour’s self-imposed limits on its economic policy, which Cam and I discuss extensively on the podcast - was to center the new government on a core set of national preoccupations and to set those within an unshakeably small “c” conservative and patriotic frame. Though the Tories themselves have been crushed and Starmer et al deserve credit for delivering that result, and though the new government may hopefully do something to alleviate “shit life” for the majority, their particular articulation of Britain’s current crisis has a perverse effect. Rather than overturning the Tory redefinition of Britain and its future, Starmer’s reframing of the Labour Party underlines the parameters of British politics set by a narrow, nationalist majority in the Brexit referendum eight years ago. And his resounding tactical victory, narrow and heterogenous though its electoral base may be, will tend to reinforce that essentially conservative message.