"The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.”

For many commentators, this is the phrase that sums up the current crisis of world politics and world power. In a truly surprising twist of the world spirit, lines from Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci have become one of the soundbites of the early 21st-century.

In #2 of the Notes on Hegemony I want to put this conceptualization of our current crisis in question. Gramsci’s notion of interregnum may have served him to illuminate his immediate context. But, it transmits to our era a philosophy of history that actually obscures how we got from his moment of writing to our present day. It thus stands in the way of thinking hard about the challenges and opportunities of our current moment.

The currency of Gramsci’s lines today today should give us pause. After all, if we take Antonio Gramsci seriously as a historical thinker, as we absolutely must, we should also acknowledge the huge gulf that separates him from the present. He was a Communist who paid with his life for his commitment to the cause of world revolution. His lines on interregnum, now the stock in trade of after dinner speeches and think tank meetings, were composed in November 1930 in a fascist jail. Gramsci was thirty-nine. He would die at 46, his fragile health irrevocably broken by harsh imprisonment.

With morbid symptoms Gramsci may have been referring to fascism. Alternatively, he may have been criticizing the turn to the ultraleft of the Italian Communist party under pressure from Moscow. His medical language evokes Lenin’s famous denunciation of left communism as an “infantile disorder”.

Wondering about the popularity of Gramsci’s lines today, I’ve come to think that it may have something to do with the way in which they combine drama - crisis, birth, death, interregnum - with an undertone of reassurance. If this is true, it is a deep historic irony. Gramsci derived his fortitude and belief from his Marxist understanding of world history. Today his words serve very different purposes.

What do I mean by reassurance?

First of all, Gramsci’s quote implies a definite direction of historical travel. We know what is old. We know what is new. We may currently be in crisis, but it is only a matter of time before “the new” will eventually be delivered.

A transition from old to new might imply significant change, which could open us up to thinking about radically different futures. That might be good news. But it might also be disturbing. Once again reassurance is provided by Gramsci’s definition of the crisis as interregnum. The present is an inter-regnum, because it a period between two orders. It may be messy now, but a new era is on the way.

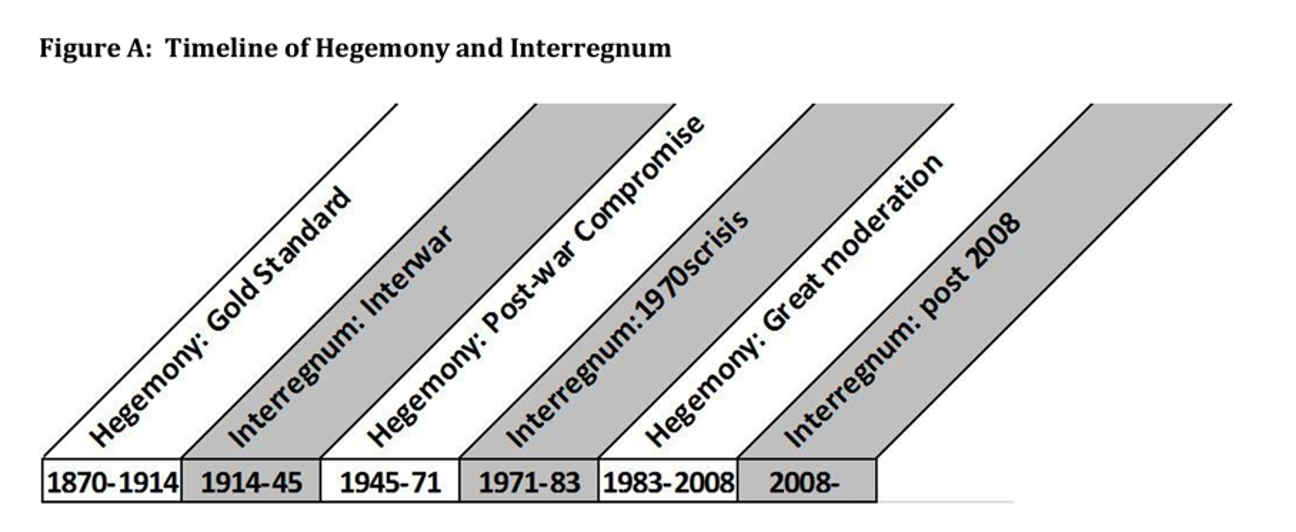

This kind of historical thinking is not confined to Gramsci. It is nicely illustrated, for example, in this conventional chronology of modern economic history.

Once cast in terms of the sequence of regnum-interregnum-regnum our current disorder becomes merely a passing moment. Given this sequence, who could doubt that a new white bar lies ahead of us. In this graphic, the grey phase of interregnum that began in 2008 already has a right-hand demarcation, even if no date is, as yet, attached to the endpoint.

A further point of certainty amidst Gramsci’s interregnum, is that we can confidently distinguish what is morbid from what is healthy. This again implies a superior vantage point, something that one might think would be in jeopardy in a true moment of crisis.

The obvious question is: what is the basis for Gramsci’s judgement? This troubling question is especially pressing if Gramsci was, in fact, applying the label morbid not to fascism but to those he disagreed with in the ranks of the international communist movement. Was this a medico-technical diagnosis? Or, was his judgement, like Lenin’s, a political act, an act of polemic, stigmatizing disagreement? In which case the naturalized conception of crisis is, in fact, disguising a political clash.

Finally, and most fundamentally, Gramsci’s diagnosis locates the current crisis within history imagined as a natural cycle of life, of birth and death.

What will happen to “the old”? - It must die.

And how will we arrive at the “the new”? - It will be born.

These seemingly obvious turn of phrase, especially the latter one, pose a puzzling question: If we can imagine death as an endogenous process of exhaustion, the same is not true of birth. Who or what will give birth to the new?

If something is born - rather than developing, mutating or being built from within - this implies a body that gives birth to it. If a historical period of confusion, uncertainty and latent crisis is imagined as the labour of a protracted birth, then the underlying reassurance lies in the assumption of a historical mother carrying “the new era” to term, a womb, a nurturing place where the new is gestating and from which it will, it must eventually emerge.

“The new” won’t be know until it is born. But this womb of history tacitly evoked by Gramsci’s lines is a transhistorical given.

For Gramsci this womb of history was presumably some version of the Marxist historical dialectic. What is its equivalent for those who invoke Gramsci today? We have no adequate answer.

This is what I mean by saying that Gramsci’s formula, for all its insistence on crisis, frustration, interregnum and morbidity, actually offers us comfort. The distant echoes of Gramsci’s marxisant philosophy of history serve to reassure us that:

there are clear normative standards (morbid v. healthy)

there is a clear and necessary direction of history (old v. new)

there is no threat of true novelty, because we are in a sequence of regnum-interregnum-regnum, which implies repetition not innovation.

and there is an overarching naturalized structure which governs the process, the womb from which the new will eventually be born.

We find this same logic in another influential formulation of the history of hegemony: Giovanni Arrighi’s conceptualization of hegemonic sequence.

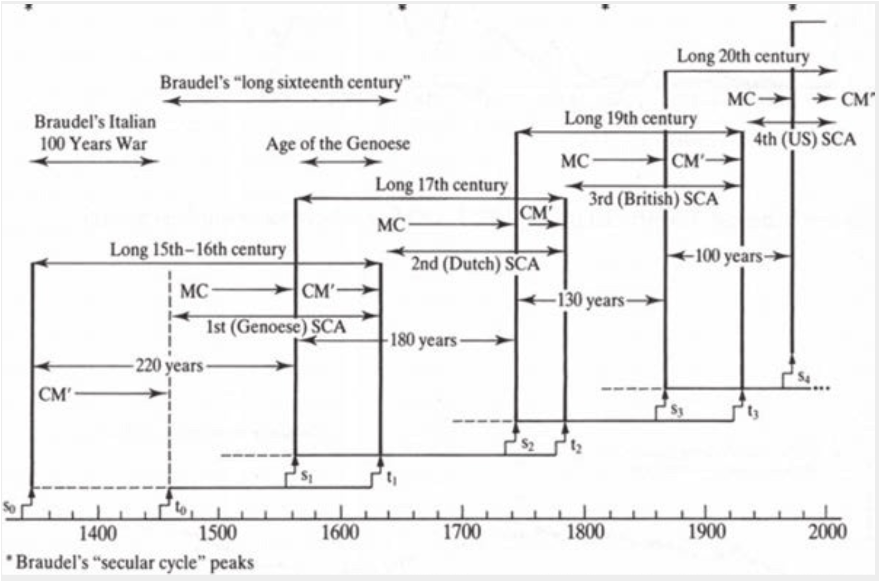

Arrighi’s complex historical narrative is summarized in this sequential diagram.

What is striking about this graph is the self-confidence with which it connects the medieval period and the 21st century in a single sequence. There is a general upward drift of the schematic. This presumably indicates economic growth. But there is no vertical axis specified. The basic message is not one of transformative development or growth, but of a repeating pattern.

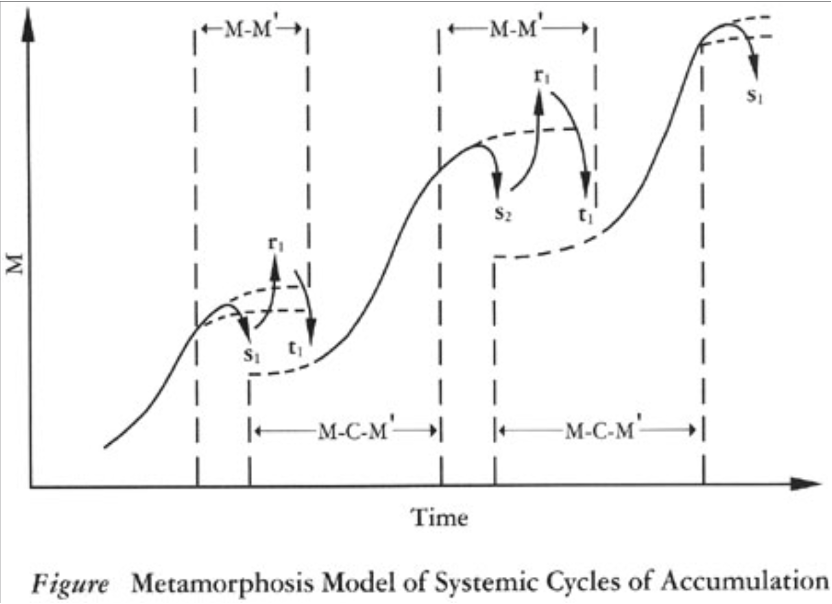

The underlying structure, Arrighi’s “womb-mechanism”, is spelled out analytically in a separate graph.

This sequence has a time dimension. But since it is imagined as repeating, over and over again, it has no specific historical referent. The sequence of historical eras - Genoa, Netherlands, Britain, USA - is born out of an underlying mechanism that functions transhistorically, as a logic of metamorphosis.

To label this “transhistorical” is an overstatement perhaps. But only just. What enables seven hundred years of history to be viewed as a single repeated sequence of regnum-interregnum-regnum, is a notion of capitalism that centers on markets and in particular finance. It is this assumption that allows a narrative to be unfolded that begins in the Middle Ages and continues down to the present, in which the emergence of capitalist agriculture, or the factory system, or the fossil fuel revolution, or the age of imperialism, world wars and state-managed capitalism make no significant difference. From the middle ages to the 21st century what we see over and over again is the sequence of accumulation by means of M-C-M’ giving way to a purely financial M-M’, which in turn is superseded by a new cycle of M-C-M’.

To my mind such schematic analysis betrays what it sets out to analyse. Like Gramsci’s lines it combines a declaration of crisis with a reassurance of knowledge that denies the dissolving effect of the crisis.

Arrighi’s formulation reduces modern history to nothing more than a repeating timeless sequence. Models of this kind gesture to the confusion and terror of interregnum, all the while reducing that phase of disorder to something temporary, recurring and predictable. The model gestures to historical development - the upward step of phase after phase - but actually reduces radical change to repetition. After one hegemony what we look forward to, is simply another.

This line of thinking is not just simplistic. In the current moment it is dangerously so. To the drama of America’s evidently waning hegemony it adds the intensity of the follow-on question: who comes next? This question - far from necessary - is framed by the assumption of historical repetition - hegemon-interregnum-hegemony. In the current moment there can only be one possible answer: CCP-led China. That in turns eggs the flailing American elite on to a more intense rearguard action. But why assume that in the 21st century there will be a successor to America’s 20th century power?

Any serious examination of the foundations of modern power actually suggests that this kind of cyclical or sequential view of history is misplaced.

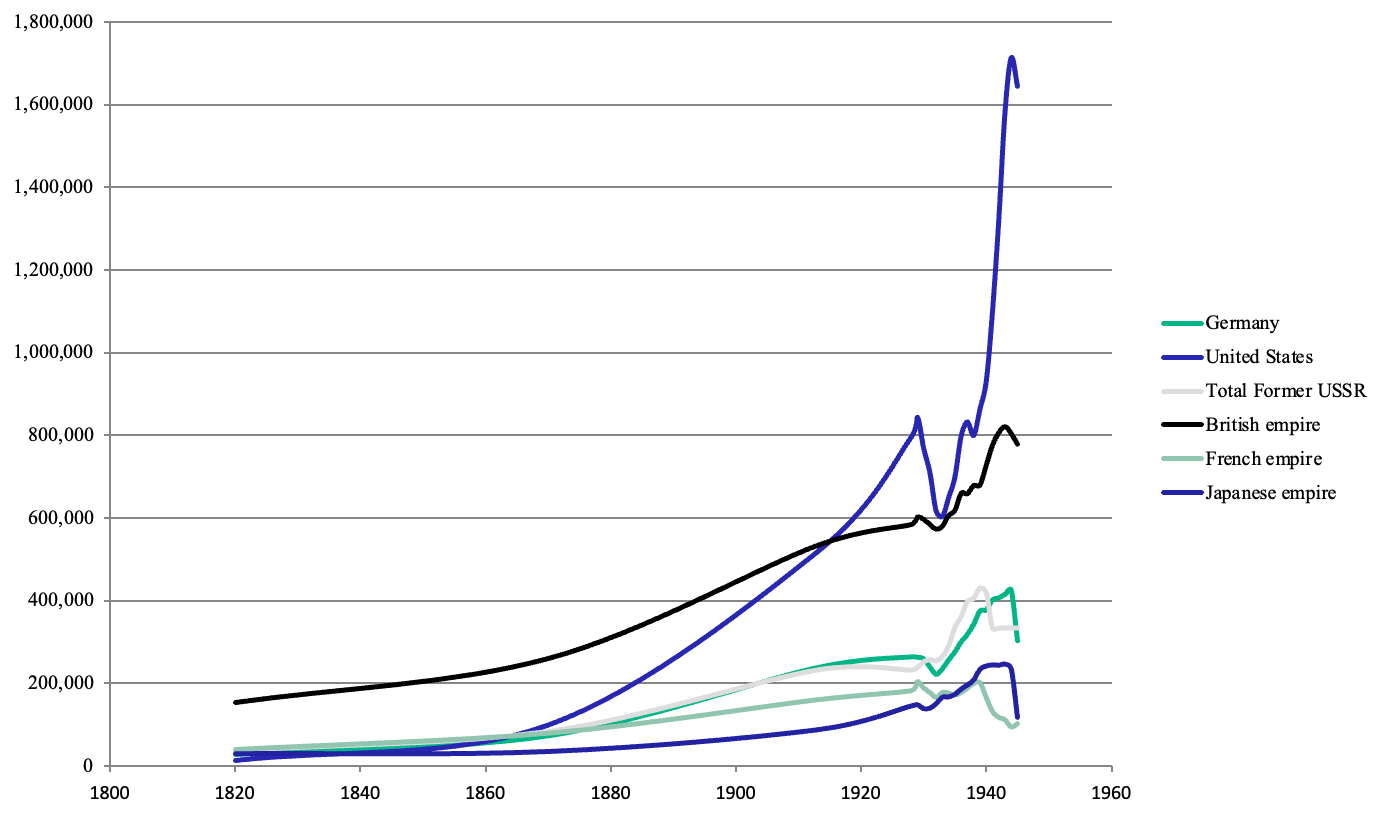

Take GDP as a proxy for power resources and think about the kind of intellectual gymnastics which are necessary to turn history as depicted by GDP below into the sequence described by Wallerstein and Arrighi’s formalism above.

Source: Maddison Project data

As for the long-run continuity, global GDP prior to the 19th century is so low that it can not be sensibly depicted on the same graph extending into the 20th century. This is also true for economic heft and destructive power. Of course, there were highly destructive wars, in the 17th century for instance, but their violence unfolded according to a very different logic from that in the 20th century.

And as for the pattern of change, what we see is not a neat sequence of substitutions in which one hegemon displaces another, but rather something more akin to “piling on”. This is history not as repetition, but in Mark Blyth’s wonderful phrase as a “one-way trip into the unknown”.

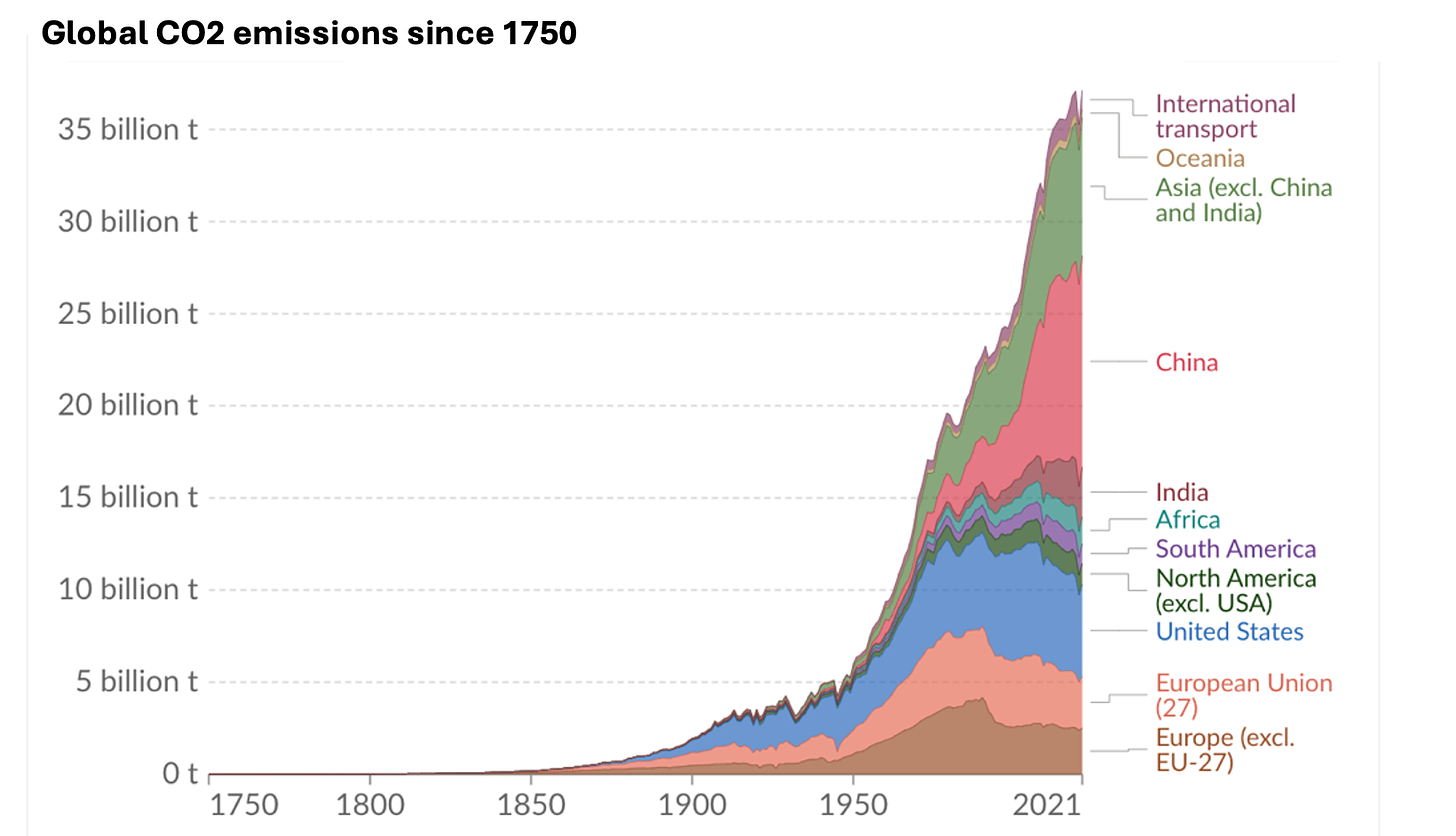

This idea comes more naturally when we talk about the ecological crises such as climate change. In that domain of world history, it is climate deniers who indulge in cyclical fantasies about global temperature. But global heating is a direct counterparts to this graph of GDP as we can see if we juxtapose it with the chart for CO2 emissions.

My basic proposition is that we should maintain the same awareness of radical change that thinking about the climate crisis has sharpened in us, also when we are thinking about the history of global power.

In that spirit I see the construction of global hegemony in the 20th century not as a repetition of something familiar, but as itself a venture into the unknown. To put it simply, I see global hegemony as a 20th-century problem.

If it helps, think of America’s 20th-century power as “oil power”. In many ways that is quite misleading. It suggests a simple sequence, starting with Britain’s coal empire, followed by American oil and China and its renewables. This too is a bad model. We know energy history does not work like that. But, at least the discrete sequence of coal, oil, renewables serves to put distance between us and Arrighi’s even less helpful formalism of the endlessly repeating logic of M-C-M’, M-M’, M-C-M’.

We will do even better to think of the problem of global hegemony as a historical ellipse. The problem was posed for the first time in the late 19th century, as the force of imperialist competition ruptured the bounds of the British Empire. In our current era of G20/G30 multipolarity, it is well and truly beyond its sell-by date.

Of course, the distinctive 20th-century visions of global power had precursors. They had preconditions. Something had first to constitute our modern conception of globality. This happened through the global system of power, communication, transport and commerce created by the British Empire in the 19th century. This constituted for the first time what Michael Geyer and Charles Bright called the “global condition”. All too often this encourages thinking in terms of an Anglo-American sequence. But again this underestimates the power of accumulation and overlay. Compared to US power in its mid 20th-century pomp, the British empire was a thin mesh of networks. The British empire maintained its grip with extremely limited resources in large part as a result of the weakness of its rivals.

This weakness of British global power was exposed in the era classically diagnosed as imperialistic by Hobson, Luxembourg, Lenin, Bucharin and others. In many ways they were the first thinkers of globalism and we mistake them fundamentally if we equate them with timeless millenial views of empire so common in popular and in some academic history writing. Though we label this imperialism and it entailed a brutal round of colonial expansion and occupation, the basic logic of this era was defined by the development of a new cluster of nation states - Italy, Germany, Japan, USA in addition to Great Britain, France, Russia - each of which staked their claim to a “place in the sun”. The brutal logic of this era was most starkly on display in the collective efforts at imperialist coordination, above all in the Berlin conference of 1884-85 on African partition and the eight-nation coalition to subordinate China.

It was this new configuration of multi-sided global competition between powerful nation states, starkly visible by 1900, that defined the 20th-century problem of hegemony.

The scale of this problem of order was altogether new.

Global capitalism had never operated on the scale that it was operating in the early 20th century.

Nor had imperialist competition rooted in powerful nation states ever taken on such intensity. There had never been a moment of apocalyptic continental violence like World War I. And the rest of the century would confirm that escalation. The arms race of the 1930s was of a different order to that before 1914. And the thermonuclear age and the threat of mutually assured destruction raised that threat to an even greater level. Future notes to follow on this.

You can read both those escalatory tendencies off the power curve above. Indeed, as I argued in Statistics and the German State, the construction of the national economy as an object of government, expressed in the form of national economic statistics and a concept like GNP, is an effect of this process. The modern state and the national economy are twins.

Added to which, the problem of problem of hegemony as a novel 20th-century problem is never merely a matter of great power politics or economic management. It was always deeply political. Governing elites had never before faced political, social, cultural and economic challenges in the form of democratic mass movements, as they did in the early 20th century. By the mid-century the colonies would be ungovernable.

World War I was a decisive turning point. But already in the early 1900s, revolutionaries could see the explosive potential in the situation. That is what made a Lenin’s conception of revolution different from a mid-19th century revolutionary like Karl Marx.

The realization that the world had fundamentally changed is also what made fascists different from 19th century reactionaries. They knew they had to be revolutionaries, of a sort. In the imperial sphere, likewise, fascist plans for territorial expansion were more self-consciously racialized and hyper-violent even than those of conventional colonialists in earlier eras.

Large-scale population displacement and clearance as a mode of ordering became common place.

Maintaining any semblance of the status quo under these conditions was a novel challenge. It required conservatives and liberals too to abandon their 19th century dogmas and to innovate in ideological terms. Hybrids like christian democracy, “new liberalism” and reformist social democracy were characteristic expressions of the moment.

The British elite were the first to realize the scale of the new problem of maintaining the status quo under these dramatically changed circumstances.

From the 1890s, the British Empire, facing a novel array of threats across the entire globe was scrambling to stabilize its position. In the Committee of Imperial Defence it actually built an organization to conduct fully global strategy. British naval planning encompassed the entire globe. New, convention-breaking alliances with Japan and with France and Russia promised safety. But in 1914 they also sucked the British Empire into a ruinous great power war centered not in the colonies or in great naval battles, but in continental Europe.

It is not for nothing that both Mussolini and Hitler idolized liberal wartime Prime Minister Lloyd George as the visionary politician of the moment. It was not simply his genius that made John Maynard Keynes the key thinker of liberal politics and economics of the new era. Britain bank-rolled the Entente’s war effort initially on a public-private basis, operating through JP Morgan on Wall Street, which prior to 1914 had still been a peripheral node in the global financial system. More on the novel architecture of this system in a future post.

But by 1916 it was clear that only the United States had the power to manage the new configuration of global forces. The weird architecture of global mobilization in the first phase of WWI could not be sustained without at least the approval of the government of the USA. This is the story of my book, Deluge.

The economy, as measured by novel statistics of national income, would be America’s trump card. But that in itself is not an obvious fact. It was an effect of particular circumstances. 1916 is a pivotal moment because with the inconclusive battles of materiel at Verdun and the Somme, following the “hunger winter” of 1915/1916, it became clear that purely military operations were at an impasse and this meant that war production and home front stability would take on a new and central role in determining the course of the war. War became a new kind of totalizing war. It was also an election year in the USA, arguably the first formal democratic event (as opposed to a revolution) to matter on a global scale. Certainly, it was the first US election that was watched with baited breath by political classes around the world.

It was out of the historically specific, financial and economic urgencies of World War I, that a new American-centered network of power emerged. This was something new, something architected and built to meet the urgency of the moment. There was no womb of hegemonic logic from which the US power was born to replace a dying British global order. It was not the inevitable sequence of monetary logic that ground through its inevitable development to make the dollar replace the pound sterling. It was war and war finance. The dollar in the 20th century would play a role quite different from sterling under the 19th century gold standard. Furthermore, America’s global power did not substitute for British power. It overlayed Britain’s own efforts, first in World War I, then in the interwar period and finally during World War II, to master the new hegemonic problem. In crucial areas, notably the oil fields of the Middle East, it was not until the late 1960s that the the US finally took over.

The strategists of American liberal internationalism around Woodrow Wilson struggled to build a new network of power and influence to place the USA atop a stabilized order. Whether morbid or not, it produced some strange configurations. Wilson, a committed son of the American South, steeped in conservative, Burkean liberalism, found himself feted by European socialists.

Wilson’s project was a first attempt. When that failed it was replaced in the 1920s by disarmament and dollar diplomacy. When that failed in the Great Depression what emerged from the wreckage was the US project of globalism of the 1940s, sustained by the New Deal order at home and the strange power bloc of progressive export-orientated business, Northern labour and the Jim Crow Solid South.

Each of these projects was a novel answer answer to the novel problem of how to tame imperialism and govern capitalism under democratic circumstances. They were experimental in the sense that this had never been done before.

When the US finally did manage to marshall its power for the consolidation of the Cold War bloc after 1945, it was a kind of power that no state had ever exercised before. It would be a unique high point and it would depend on a continuing, on-going scrambling effort at innovation. The most commonly cited example of successful American hegemony, the Marshall Plan was not Plan A for the postwar world, it was not even Plan C, it was Plan D. And it would have been unthinkable without the no less unprecedented form of state power represented by Stalin’s Soviet Union.

America’s age of hegemony was not an answer to an interregnum. It truly was new. It was thus not the latest iteration of some familiar form of power. It did not replace the British empire. The British empire was reinventing itself too in response to the new challenges of the early 20th century. It was overtaken by the US and nested itself under the wings of that power. It was not something born. It was built.

And if that is true for the early 20th century the question of how 21st century global power will be organized should be considered no less open. Certainly, our problem right now is not that the old is simply dying. Things are far from that simple. In certain crucial respects “the old” is hanging around and indeed seeking to mobilize new strength. At the same time the principal challenger may be “new” in the sense of unfamiliar. But the CCP-regime draws inspiration from a first successful century of ascent, evokes ancient Chinese history. And what its underlying drivers are, is a matter of contentious debate.

What is old and what is new, what morbid and what vigorous, what the underlying generative logic of history actually is, these are all questions that are at this moment up for debate. We are, therefore, experiencing a crisis of confidence and a period of uncertainty, that is far deeper than talk of an interregnum à la Gramsci implies. To be clear this does not necessarily mean more lethal or more tragic than the epoch that cut short Gramsci’s life. Our normality, however catastrophic, may be manageable. The environmental clock is ticking, but the majority of us are no longer poor. We live longer. Today, Gramsci’s life could probably have been saved. There are gigantic technological resources that democratic and progressive crisis-management could draw on. What we must let go of, is the false mantle of confidence and historical clarity that evoking the concepts of an earlier epoch entails. Abandoning talk of an interregnum may rob us of certainty. But rather than a council of despair this is simply a demand of realism. What that promises, is the chance to trade historic phantoms for new projects and the exploration of the actual possibilities of the present.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. In an exciting new initiative we have launched a Chinese edition of Chartbook, on which more in a later note. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates.

I keep them as low as substack allows, to ensure that backing Chartbook costs no more than a single cup of Starbucks per month. If you can swing it, your support would be much appreciated.