Spurred on by my friend Grey Anderson of Verso and inspired by a visit to Dalian, Beijing and Shanghai, I’ve been thinking a lot recently about the problem of power in the 21st century and US hegemony. This is the first of a series of notes on the topic.

Being the first, this is the most basic, clarifying some elementary points about power.

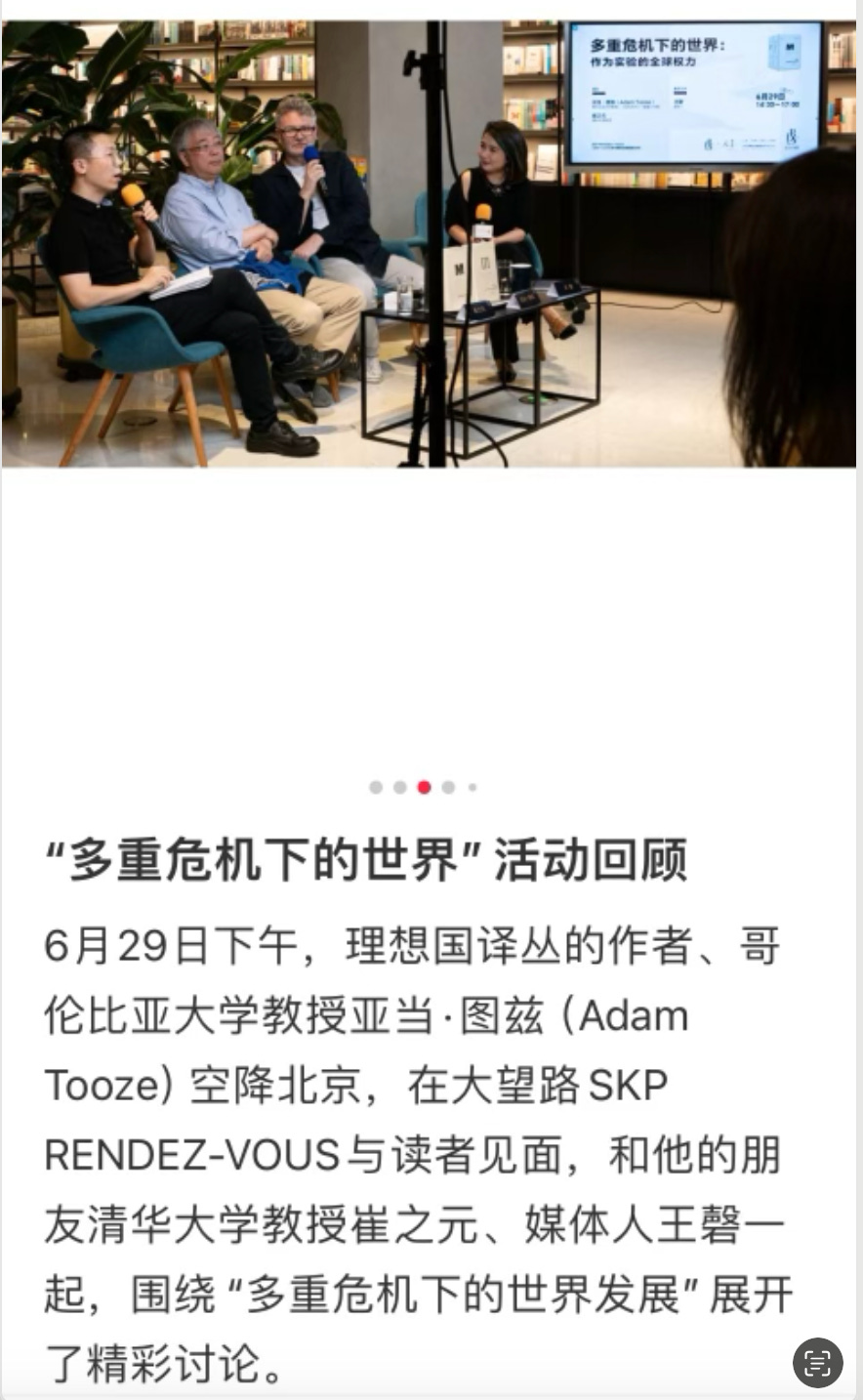

It came to me as part of an on-going conversation with Barnaby Raine about the themes of power and freedom and a discussion in Beijing with Cui Zhiyuan moderated by Wang Qing, hosted by Imaginist, the publisher of Crashed and Deluge in Chinese translation.

Wang Qing is an international correspondent and one of China’s leading influencers and commentators, focusing on feminism, European and global affairs. She co-hosts an influential podcast and is the editor of the recently launched Chinese edition of Chartbook newsletter.

Cui Zhiyuan is a Professor at Tsinghua University. He is a leading member of China’s “New left”, an exponent of experimental governance, sometime collaborator of Charles Sabel, a prolific author and editor of Politics: The Central Texts, a selection from Roberto Mangabeira Unger’s Politics.

Ahead of our conversation in Beijing, Cui Zhiyuan and I were looking for the bridge between our lines of thinking and I think we found it in the idea of “global power as experiment”.

The train of thought as it has developed on my side goes as follows:

1. Michel Foucault made a famous distinction between a repressive and productive conceptions of power. Foucault’s metaphor points to regimes of sexual regulation, prison, school, barracks and factory as the sites at which modern subjectivities are produced.

Foucault’s notion of power forms a fruitful affinity with Marxism, which saw the site of production, as the key location for the generation and extraction of surplus value. The factory, not the market was the key to understanding both the accumulation of capital and the production of a new type of historical subject, the worker. Big h/t to Barnarby Raine on this.

2. But look out at the modern world, gaze in awe at the landscape of a modern mega city like Shanghai and what do you see?

You see the products of the factory in the literal and metaphorical sense, mass-produced people and things. You see the discipline of political power – party and state merged. But you also see something else, something not captured by either of these notions of power.

What kind of power built this forest of giant buildings, these mountains of steel and concrete?

What animates the millions moving through those myriad streets? What organizes the giant flows of money and resources necessary to sustain such huge concentrations of human activity?

I don’t believe that this can be reduced to the product of discipline or routine production of subjectivities or desires. In a modern megacity, in its towering buildings, giant developments, huge roadways and infrastructure, in the individuals that summon the energy to inhabit that space and in the state organizations that frames them all, you see something else. You see the effects of a kind of power that reshapes the material and social world through discreet, one-off acts of mobilization, interventions and experiments. Each one of those buildings in their higgledy piggledy accumulation is a monument to this kind of power.

3. Think of the difference between factory production and high-rise construction, or the difference between schooling and the life-long and haphazard business of self-fashioning. Think of the difference between making a disciplined army out of raw recruits and actually using that army in war.

Factory production involves routinized, endlessly repeated processes. Drilling an army is, likewise, a matter of inculcated routine. Constructing buildings and fighting a campaign involves quite different processes and energies. Of course, both may involve standardized components, but they are assembled and arranged, each one according to a specific design and vision. Each choice is distinct, idiosyncratic, particular. Each has irreversible consequences.

As Clausewitz preached in the wake of Napoleon’s devastating defeat of post-Frederician Prussia in 1806, anyone who confuses the mechanical drilling of an army with the historic wager of war, is destined to defeat.

4. For this third mode of power, following the lead of Charles Maier’s recent book, project-power might be a suitable label.

A project in this sense is the historically specific, intentional mobilization of multiple resources around a significant objective on whose success and failure important things depend.

Hierarchy and inequality have structural preconditions, but they are produced and reproduced through clashing, rivalrous and unequal projects. Structures of power and inequality are the result not simply of inherited, given structures, but of repeated success and failures in a churning melee of projects and counter-projects.

You can build a revolutionary party and discipline its member. You can organize a large labour movement, but if you want to change the world you have to size up your putative friends as well as your enemies, gauge your relative strength, and pick the moment to strike. That was a bitter lesson learned by the CCP in Shanghai in 1927.

At the level of individual biography you can inherit social and cultural capital, but for all but the tiniest über-elite, reproducing social hierarchy has an irreducible dimension of project. Privilege requires its own kind of performance. Exams have to be taken, interviews aced, meetings mastered, KPI’s met.

A poor country is, according to basic economic logic, a growth opportunity waiting to happen. Huge profits beckon. But, nevertheless, billions remain poor.

It is the success and failure of projects that make the difference.

5.In principle we can make the distinction between three forms of power - discipline, production and project - at any scale and across many domains.

One might, for instance, distinguish between the production of heterosexual desire, the rules of dating at a specific time and place and the logic of a dramatic declaration of love. They are all interrelated, but each involves a different logic of agency and power.

The drama and power dynamics of a couple’s romantic balcony moment can be made to disappear into statistics of marriage and fertility. They will then appear as merely a moment in a logic of discipline, a social structure, or a cultural trope. But that is the effect of a subsumption. It does not erase the particularity of a place, or an actual moment between two people, or its consequences for their biographies.

That kind of subsumption has even less force when we think about larger scale projects.

6. Classic instances of the exercise of project-power would include:

Large-scale construction projects – building cities, mega-towers, damns, tunnels etc

Launching a war and/or conducting military operations.

The calculations of revolutionary or counterrevolutionary politics.

Programs of large-scale economic development, whether public or private.

Constructing a network of international alliances.

7. The history of capitalist accumulation is a history of projects. That is what the skyscrapers of a megacity so vividly testify.

The history of state power and hegemony is a history of project-power.

Of course, the exercise of hegemony has involved both production and discipline. It is constrained and shaped by geopolitical givens. But US hegemony, the only version that has ever operated at a truly global scale, is best understood as a project.

This is true also for the British Empire the power that framed the growth of Shanghai as a center of multi-national imperialist emplacement for almost a century. It is not for nothing that John Darwin in his magisterial history coined the phrase “Empire project”.

As I will argue in a later post, the British Empire and 20th century US hegemony were both distinct and original projects.

8. The aim of these series of notes is to describe US hegemony as project. Not as a monolith, not as a natural sequel to earlier forms of global power, but as an original, precarious innovation, one that has had to be repeatedly renewed and reorganized.

It may fragmented and exhausting itself in the current moment but it is not doomed to extinction by a quasi-natural sequence of historic cycles. And whatever global power structure emerges in the future is unlikely to resemble the past.

I began to sketch this history in my books Deluge, Crashed and Shutdown.

In the LRB lecture I told a story of American power that involved a whole series of innovations in power.

This is also the way I would tell the story of the creation and survival of the dollar system.

9. As Foucault taught us, power and knowledge are intimately imbricated. Different kinds of power constitute different kinds of knowledge and visa versa. So this raises the question of what kind of knowledge is particular to project-power.

Project-power has more diverse applications than the tightly focused set of disciplinary practices involved in the production of “man” and the convergent forms of knowledge that emerged in the early 19th century centered on that same object.

Projects are works of engineering, developmental economics, military-science, psychology, political tactics and strategy.

If one had to generalize, one might say that the form of knowledge that is particular to project-power is historical knowledge. As discreet interventions located in time, interventions that make a difference, projects are necessarily located in histories.

Relationships or parenthood are projects that define our biographies.

Political engagement ties us meaningfully to collective history. It is the active counterpart to Hegel’s prayerful reading of the daily news.

A grand construction project and a military operation are necessarily located in histories – in the evolving history of a city, in the chronology of architectural styles, or the annals of military endeavor.

10. The relationship between project-power and history is reciprocal.

The modern Western sense of historicity was shaped in the early modern period by the beginning of self-conscious project-style action by European states.

The literary form of the novel was shaped in the 18th and 19th centuries around the adventures of the modern self, romantic and otherwise.

From the 19th century onwards, statistical time series have become the preeminent medium in which we narrate the ups and downs of “the economy”.

11. Following Latour et al, one could go one step further.

Modern scientific knowledge is not produced in the manner of factory-production. Nor is it reducible to “discipline”. Neither image adequately captures the creativity, originality and idiosyncrasy of discovery.

The basic building blocks of modern science advance are experiments.

Experiments organize resources, instruments and actors towards a decisive test. Though an experiment should be reproducible – like factory production - that is secondary consideration, like the ability to safety test a giant building. What is inscribed into the evolving narrative of the forward march of scientific knowledge is the first decisive experimental test, or, more precisely, the documents that report it.

Described this way, experiments have all the qualities of a project.

Viewed synchronically, modern technoscience can appear as a disciplined system. Viewed diachronically science is driven forward by the accumulation of interconnected knowledge projects.

12. This leads us to the dizzying conclusion that the project is the form of power and agency common to the generation of

scientific knowledge

capital accumulation

state power

and modern subjectivity.

13. This in turn allows a further series of cross-connections.

The giant complex of the modern technosciences might be thought of as a megacity of knowledge – a sprawling, uneven terrain of accumulated experimental results and investigative projects.

Conversely, if we can think of experiments as projects, we can think of large-scale projects of power – a national economic development project, or a military campaign – as experimental.

Such exercises of project-power test the limits of what is known and what is possible.

I think of the problem of hegemony as it emerged from the crisis of imperialism at the turn of the 20th century, as a quintessential example of great power politics as experiment. More on this in later posts.

By definition the outcome of such ventures is not known in advance. Holders of power sometimes convince themselves otherwise. They imagine and may even announce that success is certain, that the “plan will be met”. But that is more often than not a recipe for disfunction, disappointment or self-deception.

This is where I converge with the line of thought developed by Cui Zhiyuan on experimental governance. And also with the account of plurilateralism (in the climate policy domain) to be found in Charles Sabel and David Victor’s Fixing the Climate.

14. The advance of power-projects at every level can be described in progressive terms as the advance of knowledge, productivity and control. The gains in terms of human survival, economic advance and empowerment, are real.

But every advance also opens up new forms of alienation, new forms of subjugation, new uncertainties and risks.

Tracking, monitoring and diagnosing the balance has spawned countless projects of its own – projects about projects. This is what the sociology of the 1980s and 1990s - Giddens, Beck et al - referred to as “second modernity”, or modernity in its reflexive mode.

Interestingly, Beck insisted on the need for any conversation about a global second modernity to be based on a dialogue between East Asia and the West.

15. Since the 1970s, and with ever greater urgency in recent decades, those meta-projects - the alarm mechanisms of second modernity - have been flashing red.

Far from entering an “end of history” in which the history-making force of project-power is displaced by the humming efficiency of an established and unquestionable machine endlessly reproducing its own unalterable truth, we face the reverse scenario: The culmination and interaction of projects of growth, political power and self-empowerment, on a scale never before seen, is generating a massive and escalating disequilibrium.

The taken for granted relationship between the most basic structures of nature and the forces of human agency is being overturned. It is a sublime spectacle: gigantic, exciting and terrifying.

16. Polycrisis is one of the names for the resulting, endogenously generated radical uncertainty.

Our condition is a generalization of that which Mark Blyth once so vividly described with regard to climate breakdown:

“a giant non-linear outcome generator with wicked convexities. In plain English, there is no mean, there is no average, there is no return to normal. It’s one way traffic into the unknown.”

In Shanghai this week it was hard to escape the force of that vision, as the summer heat surged to a “felt” 47 degrees centigrade (116 Fahrenheit). In the full glare of the sun it was higher than that. A city of over 26 million people was cooking.

Every plan, every project had to be organized around the number of minutes one could handle the heat. For some that is longer than for others.

Air conditioning and the electric power supply that keep it running, become essential to survival and maintaining any kind of productivity at all. Those forced to earn their living outside suffer, whilst they wait for the sun to go down and the temperatures to fall into the sweltering 30s.

17. What is our best bet for surviving this adventure into the unknown?

The only plausible answer: more projects!

This is the backdrop against which the question of the history and future of US hegemony, the green energy transition, the rise of China should be posed.

I love writing Chartbook. I am delighted that it goes out for free to tens of thousands of readers around the world. In an exciting new initiative we have launched a Chinese edition of Chartbook, on which more in a later note. What supports this activity are the generous donations of active subscribers. Click the button below to see the standard subscription rates. I keep them as low as substack allows, to ensure that supporting Chartbook costs no more than a single cup of Starbucks per month. If you can swing it, your support would be much appreciated.

Theorizing power on a world historical scale requires a deeper dive into the extant literature. It is good to start with Foucault & foray through Marx, Latour...but your glosses reveal a lack of having really contended with their intellectual projects (no pun intended).

Read Giovanni & Arrighi. Long 20th C, and Chaos & Governance in the Modern World System. Spend some time in Marxist geography lit.

...then your thinking/theorizing about power and hegemony might get really interesting.

I say this as a fan (with a PhD in this field).

Thanks, can't say I understood all of this, but it did make me think of the kind of economic dynamism for which the US is famous, and how we keep reinventing ourselves (and inventing new technologies and entirely new industries) at the moment when we're told that "America is in decline", "Our best days are over", etc. Think about the transition from the "malaise" 70's to the invention of the personal computer and software industries, and then the development of the internet (not an American invention).

Or one statistic that still boggles my mind: The US is now the world's largest producer of oil. A complete disaster for humanity and all the other species inhabiting our planet, but also a testament to what was once called "American ingenuity."