Chartbook 295 The War of the villages: the interwar agrarian crisis and World War II (Thanatocene mini-series #3)

Watching Sunday-night TV in China, World War II-era dramas were running on at least three channels. But the world of D-Day seems a long way away. The war commemorated here on endless repeat is a guerilla war - low-tech, relying on cunning, vision and dogged resilience.

The contrast to the war as remembered in the West put me in mind of a piece I wrote ten years ago for the volume in the Cambridge History of World War II, which I had the pleasure of co-editing with Michael Geyer. It tries to offer a global overview of the war in the countryside, taking in the experience of interconnected farming systems as far apart as North America, China and India. The full essay is too long to distribute by email. So the text below is an excerpt. The full PDF with footnotes is here.

Consider this an effort to bridge the multiple histories of a global war.

Five years on from VE day and VJ day the United Nation’s first estimates of global population showed 71 percent of the world’s population in 1950 as rural dwellers. The share in Asia and Africa was 83-85 percent, 49 percent in Europe and 36 percent even in North America. The Second World War was fought in an agrarian world. Of the major combatants only one, the United Kingdom, could be described as a fully urbanized society. Even in the United States, the industrial arsenal of democracy, in 1940 43 percent of the population lived in communities with fewer than 2500 residents. The proportion in Hitler’s Germany was similar.

There are arenas of conflict in World War II that seem very remote from this rural world. The strategic air war waged by Britain and America against the cities of Germany and Japan was in many respects the quintessential urban-industrial war. If they were not able to identify a legitimate urban target, the bomber crews were instructed to empty their payload over the countryside as though it were nothing but a blank void. From the point of view of 1940s strategic bombing, it might as well have been. But even the airwar was not completely urban. Airbases were, as far as possible, sited in rural areas. Buildings and trees were perilous for air crews during take-off and landing. The term airfield should be taken literally. It was only from 1939 onwards that most runways were paved. The air war had a staggering appetite for land. By 1945, the American Army Air Force had spent $ 3 billion converting 19.7 million acres of US territory, an area the size of the state of New Hampshire into airbases, bombing ranges and other facilities. Laid end to end the runways bulldozed out of the British countryside between 1939 and 1945 would have made a 10 meter wide road, 16,000 km long. As a factor in landscape transformation the land hunger of the air war was several times larger than the postwar motorway system, which in Britain currently extends to no more than 3500 km.

But the World War was not just sited in the landscape. Nor did it explode into an agrarian world from the outside, or strike it accidentally like a ruinous hailstorm. Many of the parties to the conflict emerged from a rural world. They were motivated by its problems. And their struggle in every arena of the war drew directly on the resources of the countryside, its people and its animals. As a result of this mobilization in many parts of the world the war unleashed more profound change in the social order of the agrarian world than in any other area of society.

I

To generalize about this vast slice of humanity is dangerous of course. Agrarian systems were minutely differentiated by region, climate and type of crop. Rural society was riven with social cleavages. The gap between the landlord, the middling peasant and the precarious landless labourer was vast. But between nations the differences in the early decades of the twentieth century were nowhere near as large as they were to become. In the 1940s only the agriculture of North America and Australasia had begun seriously to mechanize. And even in the US whereas there were in 1940 2 horses, mules or oxen for every farm, there was only one tractor for every four farms and one truck for every six. The basic equipment of agriculture was still common to farms across the world. The images of rural life in America captured in the photographs of Walker Evans in the 1930s would have been recognizable to many hundreds of millions of people across the world. Farming and farm incomes remained tied to the same somatic energy regime that had determined their development for millennia. And as we have come to appreciate, this was true also of most of the armies that fought the war. At the outbreak of the war, the US and British armies were exceptional precisely for the absence of horses from their ranks. When the Wehrmacht opened a new chapter in the history of modern warfare with devastating lightning victory over France in May 1940, the vast majority of its traction outside the cluster of motorized Panzer divisions was provided by half a million horses.

If, to set the stage for an agrarian history of World War II, we are forced to choose a single common denominator of global agriculture in the 1920s and 1930s, it would be that of a crisis of modernization. Across the world the common experience was one of disequilibrium between bulging populations, increasingly disappointing progress in productivity and a diminishing margin of new land, which could easily be brought into production. The most dramatic way in which these tensions manifested themselves were in the common risks to which societies around the world were exposed. Western European last suffered outright starvation in the 1840s. But as the twentieth century began, the memory of famine or near famine conditions was common across Eastern Europe. Absolute poverty and chronic malnutrition were an everyday reality amongst millions of rural dwellers in In Southern and Eastern Europe, as they were amongst rural populations across Asia. The fact that richer societies were by the late nineteenth able to escape the specter of outright famine, had less to do with the productivity of their agricultural systems, which was far outstripped by population growth, than with their ability to access international markets at times of stress. The blockade of World War I brought hunger back to the cities of central Europe.

Meanwhile, the countryside was stirred by dramatic cultural change. Most importantly, mass literacy had spread to most of rural Europe in East and West by the early twentieth century. Famously, as recently as 1914 many of the peasant conscripts in the armies of Imperial Russia, Austro-Hungary, and Italy had little idea of the nation that they were called upon to fight for. The experience of the First World War served as a nationalizing mechanism for all of the combatants, but outside Europe and North America even in the 1930s this process was far from complete. It was World War II that would turn hundreds of millions of peasants into Chinese, Indians, Pakistanis, Vietnamese and Malayans.

At a time when the rural world was experiencing acute population pressure, land hunger was a common predicament across Eurasia. Throughout the 19th century, as transport costs fell, migration and new colonization had provided an escape valve. The closing of the US to migration in the 1920s compounded fears of “overpopulation” across Central, Southern and Eastern Europe. In the “empty spaces” of Manchuria, Chinese, Japanese and Korean migrants jostled for space.

If population pressure could not be vented by migration, this raised the prospect that a solution would be found through more or less violent redistribution of land at home. In Europe by the late nineteenth century land hunger was so severe that it repeatedly flared into “land wars”, first in Ireland, then in Russia in 1905, and then across the latifundia of Romania in 1907. The Italian countryside was in uproar after World War I as was the territory of the Tsarist Empire after 1917. Lenin’s turn to the market-based New Economic Policy in the spring of 1921 confirmed the verdict of the Russian civil war. Russia could not be ruled against the peasants. The Communists endorsed the great peasant land grab of 1917 and suspended any hasty push towards the imposition of Soviet collectivization. Across much of Eastern Europe the stabilization of the 1920s was accompanied by large-scale land redistribution. In the 1930s the land question was once again to the fore in Spain, where the land hunger of the braceros fuelled the violence of the civil in Andalusia and Extremadura.

None of these pressures would have been so acute if economic growth outside agriculture had been rapid. But, instead, the decades after World War I saw slowing industrial growth. … Between 1910 and 1920 agrarian prices surged across the world to levels never seen before, only to collapse between 1920-1921 and then to plunge again in the depression that hit commodity markets in 1928. Gloomy prognosticators had long diagnosed a contradiction between world markets and the survival of the small-scale, family farm. In the 1930s that contradiction appeared to have become absolute.

Since the mid 19th century, despite protectionist pressures, the agricultural economy had been one of the main engines of globalization. In World War I the idea of government control of the countryside had been so alien that it took even the most vulnerable combatants until 1916 to impose effective centralized purchasing and rationing. After the war the shock of near starvation suffered by many of the combatants gave a new strategic importance not so much to farmers as to food as an object of government policy. But it was the depression of the 1930s that led the developed world – the United States, Europe and Japan – to terminate the experiment with a globally integrated market for agriculture. In the decade before the outbreak of World War II all the most sophisticated states in the world were engaged in systematically reshaping their agricultural sectors into national farm economies insulated from the world market. … Nazi Germany was the most comprehensive example of national protectionism, shutting its food market completely and minimizing imports of food, fertilizer and animal feed. In Germany, amidst Hitler’s “economic miracle” surreptitious rationing of the most import-dependent foodstuffs such as meat and milk began already in 1935.

… At the same time in the East, the Soviet Union demonstrated the radical consistency of a different model. In 1928, Stalin resumed the struggle for control of the Soviet countryside that had been suspended by Lenin in 1921. Between 1928 and 1933 to build “socialism in one country” and to lay the foundations for forced industrialization, two thirds of Russia’s 25 million independent land holdings and 83 percent of its farm land were collectivized. At a stroke the Soviet regime centralized control of land, livestock and the harvest. In the process millions of farmers died of starvation. Millions more were targeted for execution and deportation as “kulak” class enemies of the regime.

In the early 1930s the rural population of the Soviet Union came to perhaps 120 million souls. Another 140 million lived on the land across Western Europe. Japan’s farm population came to 32 million with many more living in rural villages. Large as these farm populations were, they were overshadowed by the even larger populations of Asia, above all of China and India. Here land was even scarcer than it was in Western and Eastern Europe. Opportunities for political mobilization were far less. But amongst the jute farmers of Bengal or the rice paddies of East Asia exposure to the vagaries of international markets was already considerable. Long treated as a quiescent mass, one of the great questions of the early twentieth century was whether the peasant masses, the “toilers of the East” as Communist propaganda liked to call them, would rise. If they rose up would they set their own course, or would they follow a leader? What would be the cause for which they fought? Would they fight for a new social order, for the nation, or for more parochial interests? Or, would they become the passive victims of a last round of imperialist land grabs, condeming them to exploitation, forced labour, land clearance and ethnic cleansing?

To construct a frame to encompass this variegated but interconnected agrarian history of World War II, four dimensions suggest themselves. First, the agrarian world was the source of the food, raw materials, human and animal labour power for all of the combatant countries and their populations, whether civilian or military. Second, given its essential role both as a productive resource and as the foundation of rural life, land was a key target of conquest. Third, the countryside was the stage on which much of the war was fought out. We should take the notion of the battlefield more literally than we sometimes do. Fourth, in many theaters the peasants who populated this battlefield, were not passive objects of conquest, nor were they merely bystanders or victims of collateral damage, in several major arenas in Europe and Asia, the peasants, as peasants were strategic actors in the war.

II

At one extreme of agrarian experience in World War II were the United States and the White Dominions of the British Empire – Canada, Australia and New Zealand. … Even though they were not directly in the firing line, the impact of World War II on these highly productive agrarian systems was dramatic. In the wake of the crisis of the 1930s, the war further concentrated and intensified the reach of national farm policy. Agro-corporatist networks took shape that would endure down to the end of the twentieth century.

Whereas in the 1930s the problem of underemployed and surplus labor had hung over the depression-ridden farm economy of North America, wartime mobilization sucked workers off the land. Altogether 6 million people drained out of the US rural economy between 1940 and 1945. The war had a particularly dramatic impact on the racialized sharecropping system of the South. Black labor left the cotton fields en masse to be replaced by new-fangled farm machinery. After slowing in the 1930s, the introduction of tractors accelerated to reach saturation levels by the early 1950s. US wheat- and corn-farming had long been pioneers of labor-saving technologies. But in cotton the 1940s marked a turning point with government agencies encouraging the larger plantations to adopt mechanization on an unprecedented scale. Meanwhile, for those wedded to the old labor-intensive methods there was the Emergency Farm Labor Supply Program initiated in August 1942. Also known as the Barcero program it would eventually draw hundreds of thousands of Mexicans as guestworkers to the US. It was not terminated until 1962. Alongside the Mexicans, from 1943 onwards many thousands of Italian and German POWs mainly from Rommel’s Afrika Corps found themselves hoeing cotton in the fields of Louisiana, Mississippi and Arkansas.

In Europe too, low labour productivity was the curse of the farm economy. As Hitler’s Germany reached full employment in 1936 it began to suffer from an acute shortage of affordable labour. At harvest time the Hitler Youth was drafted en masse. Mechanization was much discussed, but there was not enough foreign exchange to afford the petrol or the large pneumatic tires for modern tractors. The result was an impasse of strategic dimensions. Throughout World War II an agricultural economy that fell well short of supplying Germany’s basic needs tied down more than 11 million adult workers, more than were employed either in industry or the Wehrmacht. … the Third Reich’s notorious … forced labor programme had its origin in agriculture. … By 1944 POW and foreign labour made up 41 percent of the workforce in German agriculture, the highest share of any sector.

Of course it was not just labour that Germany conquered. After its extraordinary run of victories between 1939 and 1942, one thing was clear. In World War II, unlike in World War I, it would not be the Germans but the rest of Europe that would go short of food. As the Wehrmacht advanced there was much pillaging of livestock and grain stores. In Eastern Europe the Wehrmacht had instructions to feed itself from the land. The result behind the lines in the first year of the occupation was chaos and starvation. Having established themselves in control, the Germans then moved to a system of more sophisticated exploitation that relied on large-scale purchasing operations. For Western Europe farmers this created a booming market. Highly efficient Dutch and Danish producers found that the Third Reich was willing to pay premium prices for butter. Farm earnings soared. … Farm suppliers favored by the Germans got paid, but at the price of increasingly disorderly inflation. It was the city population of German-occupied Europe that was left struggling to cope with starvation rations and rocketing black market prices. Tellingly, when peace came, the authorities in Denmark and the Netherlands sought to restore the distributive balance through currency reforms and special taxes designed to claw back the huge profits made by farmers on their edible assets.

The basic constraint on the European farm economy in World War II as in World War I was the blockade. Along with oil and industrial raw materials this cut off the high energy and high protein feeds that European farmers had become used to sourcing from tropical suppliers. The effect was to reduce yields across Europe. Thought was given in Britain to a more direct attack on the Axis food supply. In 1942 Churchill considered plans to dust Germany’s fields with a new generation of herbicidal chemicals that had been developed by Imperial Chemical Industries. The idea was rejected only because the RAF at the time was struggling to assemble a bomber fleet large enough to target Germany’s cities, let alone its wheat fields. But the Anglo-America research effort continued at full speed and herbicidal chemicals were to have formed a major element in America’s air war plan for the final destruction of Japan in 1946, Operation Downfall. As it turned out it was the British who became the pioneers of large-scale herbicidal attacks on the countryside. During their comprehensive agrarian counter-insurgency campaign in Malaya between 1952 and 1960, the British made heavy use of the chemical what would soon become notorious as Agent Orange to clear security perimeters and destroy “bandit crops”.

For much of World War II, in large parts of Western Europe the countryside was a place of relative safety, a place of evacuation for children, a place where one could hide from totalitarian persecution or retreat into “inner emigration”. It was not until 1943 in Italy and then from June 1944 in France, Belgium and the Netherlands that the rural population once more witnessed the spectacle of modern war fought over the fields, hedgerows and dykes of the classic battlefields of Europe. The final campaigns of the war saw a vast escalation of firepower … As a result, when fighting bogged down for weeks on end, as it did around Monte Cassino or in Normandy, the destruction was vast. Most damaging of all was the defensive measures of last resort – inundation. In 1943 the Germans flooded the Pontine Marshes to form a defensive belt South of Rome, unleashing a devastating return of Malaria. … But even without such desperate measures, the rural landscape could present a serious obstacle to modern, fast moving warfare. For tank warfare the undulating, empty desert or the steppe was the ideal terrain. By contrast, the dense hedgerows of Normandy, the famous bocage, provided the defenders with ready-made fortifications on which to base a static defense. In the end, thousands of tanks had to be fitted with improvised hedge cutting equipment to bulldoze their way through the French field system.

The image of an American-made Sherman tank with its steel bocage cutters smashing through the legacy of hundreds of years of French peasant labour is a fitting one to characterize the experience of West European farming either side of World War II. Technological “catch-up” was one of the defining concepts of postwar economic growth. … In West Germany where there had been 30,000 tractors before the war, by 1955 there were 462,000.

III

…. The European search for Lebensraum, of course had a long history. But by the late nineteenth century the main axis of imperialist competition had shifted. If World War I was an imperialist war, it was about more abstract concepts such as spheres of interest, or control of industrial raw materials and markets, not farmland. The revival of large-scale, state-organized programmes of conquest, land occupation and agrarian colonization, was one of the striking and apparently anachronistic feature of the 1930s. The three most aggressive powers - Imperial Japan, Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany – were unprecedentedly explicit and unabashed about the way in which they linked war and imperial conquest to the resolution of problems of the domestic social order.

Abyssinia was Mussolini’s most violent and spectacular land grab, justified explicitly in terms of the need to secure living space. But the most sustained program of fascist colonization was directed at Libya. … In October 1938 Governor Italo Balbo personally commanded a fleet of 16 ships carrying 20,000 Italian peasants destined for Tripoli, where they were to form the avant-garde of a new settler generation. By the time Italy entered the war in 1940, these agriculturalists had doubled in number, making up 40 percent of the colonial Italian population. … There is a striking similarity between Balbo’s project in Libya and Japan’s program of settlement in Manchukuo in the 1930s. The coincidence of the Great Depression with the Japanese Army’s aggression in Manchuria after 1931 created a new fusion between external aggression and schemes for agrarian improvement. …. The aim was not to import food, but to export Japan’s surplus agrarian population. This culminated in the 1936 “Millions to Manchuria” program that proposed to move 1 million peasant households to Manchuria. Given the scarcity of good land in Japan, experts calculated that fully 31 percent of all existing family farms were non-viable. … By the early 1940s almost a third of a million Japanese had been lured to Manchuria by the promise of generous allocations of land. It was by far the largest settlement project realized by any of the axis powers.

Both the Italian colonization of Libya and Japan’s emplacement in Manchuria were extremely violent, “warlike” processes. The path for Balbo’s colonization was cleared by a violent pacification campaign against the Libyan Bedouin, which culminated in herding tens of thousands of men, women and children into desert concentration camp where they died along with their livestock. In Manchukuo the Japanese settlers found themselves occupying what amounted to a guerilla war zone. The land allocated to the incomers was extracted from existing Chinese colonists at gun-point. To the North the Japanese homesteaders were menaced by the Red Army. After the Kwantung Army’s shocking defeats in the border battles of 1939, the Japanese settlers found themselves designated as “human pillboxes” reinforcing the exposed northern flank. In both cases violence and settlement were integrally linked, but to the degree that both the Italian and Japanese projects originated as a strategic response to the crises of the early 1930s, they shared an oblique relationship to the new vectors of violence unleashed by Hitler’s aggression after 1939. The vast cost of his African ambitions left Mussolini struggling to keep up with the pace of the main arms race in Europe. Though Italo Balbo’s track record as a man of fascist violence was impeccable, his commitment to colonization in Libya made him one of the leading opponents of Mussolini’s decision to join Hitler’s war. Likewise, the strategic direction of Japan’s expansion into Manchuria was northwards against the Soviet Union. What soon became clear, however, was that on this axis of advance Japan would never find an answer to its basic dilemma of dependence on imported oil. By contrast, after 1940 the humiliation of Britain, France and the Netherlands at the hands of the Wehrmacht opened more promising to the South. Japan’s fateful decision in the summer of 1941 to push towards the oil of Dutch Indonesia, combined with the decision not to join the Germans in the attack on the Soviet Union and instead to launch the assault on Pearl Harbor, had the effect of reducing Japan’s settlement project in Manchuria to a regional sideshow in what was now a far-flung battle for hegemony in the Pacific and Indian Ocean. …

It would be wrong to suggest that by its comparatively late start on its career of open aggression Hitler’s regime escaped these basic strategic dilemmas. Like Italy and Japan, the Third Reich too struggled to reconcile its ambitions for Eurasian conquest and settlement with the demands of a global air and naval war against the Western powers. But what set Nazi Germany apart was the way in which the main thrust of its campaign of colonial settlement was aligned with what emerged as the most intense military theater of the war, the Eastern Front. This was not intended. When the Germans began planning for Eastern colonization in the form of the Generalplan Ost in 1940-1941, they assumed that this huge program of ethnic cleansing would be set in motion after the destruction of the Red Army. Continuing resistance by Soviet guerilla bands was welcomed as a source of renewal and hardening for future generations of German frontiersmen. By the autumn of 1941 it was clear that things were unlikely to go according to plan. But whereas in Manchuria and in Italy’s African empire the unpredictable flux of the war led away from the original axis of colonial settlement, on the Ostfront the effect was the reverse. The most savage fighting of the war, the programs of colonial conquest, the Judeocide and a draconian regime of extraction and ultra-violent counterinsurgency all intermingled in a nightmarish maelstrom.

In this struggle the agrarian expanse of Ukraine played a particularly pivotal role. It was regarded as the bread basket of the German empire that would extend from the Baltic to the Black Sea. It was one of the most dreadful killing fields of the Holocaust. Added to which Ukraine had been a key battleground in the Russian revolution and the subsequent civil war and famine of the early 1920s. And for some of the same reasons it was also the greatest arena for Stalin’s struggle with the peasantry. Not for nothing the experience of Ukraine has come to be seen as paradigmatic of the gigantic ethnic cleansing and agrarian restructuring programs that swept over the “Bloodlands” of Eastern Europe between 1928 and 1945. One of the striking features of such accounts is the passivity of the victim populations that they describe. But what is not often recognized are the peculiar conditions that created this effect in Ukraine. The flat, unforested expanses that made the Ukraine prime farmland, were particularly unpromising territory from which to mount any kind of resistance. Pursued by roving aerial reconnaissance and highly mobile armored columns, despite repeated efforts on the Soviet side, partisans could find no footing. …

…. In the swamps and forests of Belorussue, for all the appeal of their anti-Stalinist slogans amongst the remnant of the “kulak” population, the Germans faced persistent resistance. The first cadres of the partisans were recruited from dispersed elements of the Red Army, who themselves more often than not were conscripts from the countryside. Roaming the rear areas, they had little option but to join up. As outsiders, without village attachment their chances of survival behind German lines were slim. Best of all they could form a relationship with a farmwoman and seek to blend in. But in the Russian countryside there was little space for “opting out” of the war. After starving to death most of the Russian POWs they had taken during the Barbarossa offensive, in the spring of 1942 the Germans began drafting millions of Eastern men and women for factory work. The Red Army for its part issued a compulsory order requiring all male villagers of fighting age to join their local resistance center. The result, behind most of the frontline of Army Group Center and North, was a murderous three-year struggle. Anyone collaborating with the Germans faced terrifying reprisals by the partisans. The Soviet Commissars that emerged from the forest whenever the Wehrmacht withdrew were a constant reminder that Stalin’s regime was not dead. The Germans for their part punished resistance with mass executions and the destruction of thousands of villages. … Between January 1943 and January 1944 the fighting strength of the partisans surged from 103,000 to 181,000. Fittingly, in the summer of 1944 it was the partisans that ushered in the final collapse of Army Group Center. In preparation for the third anniversary of the German assault they mounted the largest guerilla operation of the war. 14,000 explosive charges severed the railway lines feeding the 3rd Panzer Army, the first German unit to face the devastating onslaught of Soviet offensive Bagration on 22 June 1944.

IV

Substantial though the partisan movement on the Eastern front may have been, it was never more than auxiliary to the Red Army. This contrasted with two arenas of the war in which the mobilized peasantry acted not as an auxiliary to the military campaign but as a decisive variable in their own right not just in the war, but in shaping the postwar order - Yugoslavia and China.

To a 21st century audience this juxtaposition of a now defunct Balkan state with the colossus of East Asia may seem peculiar. The two seem worlds apart. But in the history of early-twentieth century insurgencies the juxtaposition has an unexpected significance. … for a brief period after 1945, it was commonplace to mention the Yugoslav partisan leader Josip Broz Tito and Mao Zedong in a single breath. What they had in common was that both were leaders of autonomous agrarian resistance movements that turned victory in the war into a platform for social revolution. It was also this that made both of them into awkward allies for Stalin in the emerging global Cold War. As late as the early 1960s the American political scientist Chalmers Johnson would base his field-defining study of peasant nationalism on a close comparison of the Chinese and Yugoslav cases and he did so for pointed political and intellectual reasons. After 1949 much American analysis of China, in the spirit of the McCarthy era tended to explain Mao’s triumph in terms of “America's political and military failures, Soviet empire building and elite conspiracies”. By contrast, as Chalmers Johnson remarked, Tito’s movement in Yugoslavia was more easily recognized for what it was: the triumph of a communist led, peasant-based, patriotic resistance movement.

Neither in Yugoslavia nor in China was the communist party the obvious ally of the peasantry. In both the Chinese and Yugoslav communist parties there were loud voices who demanded slavish adherence to the maxims of Stalinist communism … It was the resistance struggle of the war that forged a new alliance between the communists and the peasants. … more conservative resistance forces discredited themselves by vacillating between opposition to the occupiers and ill-calculated efforts to suppress their Communist rivals. This opened the door for the Communist guerillas to claim for themselves the role of the undisputed champions of national resistance. Both the Yugoslav and Chinese Communist parties showed remarkable flexibility in abandoning radical policies of land redistribution and collectivization so as to avoid antagonizing the richer peasants, whose collaboration was crucial to sustaining a successful guerilla war. … In China there has been a substantial reevaluation of the significance of non-Communist nationalist resistance. But this has not called into question the fundamental significance of the peasant mobilization brought about by the war.

Though the rise of the Chinese Communist Party would prove to be of far vaster consequences, the proportional level of mobilization achieved by Tito and the Yugoslav partisans was truly spectacular. In 1945 both Mao and Tito commanded armies of 800,000 fighters, though Yugoslavia’s population was less than one thirtieth the size of China’s. …What gave the Yugoslav party a … chance was the spectacular brutality of the occupation. Faced with the scorched earth program of the Germans and the Croatian Ustasha, the Serb and Bosnian peasants were left with little option but to fight for their survival. Initially, the Serb peasantry did so by rallying around the Chetniks, who formulated their own version of peasant nationalism. But the Chetniks limited their appeal by throwing themselves into a nightmarish whirlwind of inter-ethnic conflict. The internationalism of the Communists immunized them against this temptation. Nevertheless, the Communists would have been in no position take advantage, if there had not been a decisive change in party line in the spring of 1942. At their new redoubt in Foca in eastern Bosnia the Party activists reluctantly agreed to abandon immediate revolution. The crucial issue, as Tito proclaimed, was the attitude of the peasantry and the “the peasant follows whoever is strongest”. … In February 1943 the Communist party announced that it respected the “inviolability of private property and the full possibility for self-initiative in industry, trade and agriculture”. Land confiscations were codified in 1944 under a law that limited expropriations to collaborators and ethnic Germans. By May 1945 the land fund disposed of 1.566 million hectares. To win over the Croatian peasantry the communist party there adopted a productivist agenda focusing on harvest assistance and protection for the harvest. “Not a kernel of grain to the occupier” was their creed. .. After 1945 the triumph of the Yugoslav peasant partisans culminated in a land reform that distributed 1.61 million hectares amongst 250,000 families. This secured for Tito the legitimacy he needed to assert himself against the overweening power of the Stalinist Soviet Union. In 1948 it was precisely for his failure to take action against the kulaks that Tito was expelled from the Cominform.

V

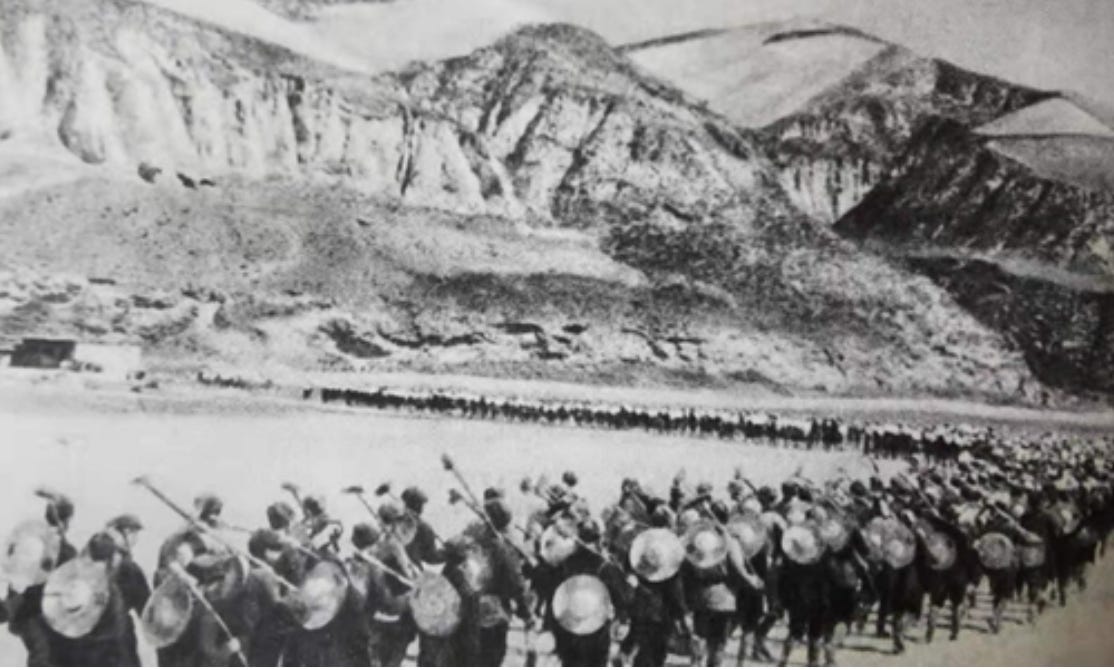

The founders of the Chinese Communist party did not come naturally to the task of peasant mobilization any more than did their Yugoslav counterparts. But by the mid 1920s, operating initially from the Guomindang’s main base in southern Guandong, driven by the orders of the Comintern and the circumstances on the ground they found themselves as organizers of a peasant revolution. It was as such that they survived Chiang Kai-shek’s onslaught in 1927, the nationalist attacks of the early 1930s and the Long March, to establish their new base in remote Northern China. In the face of violent hostility with local warlords, feuding with the nationalist forces and the counterinsurgency operations of the Japanese the CCP would by 1945 ultimately establish 19 distinct base areas spread across Northern and Central China. The largest of these base areas, notably Jinjiluyu with a population of 29 million and 7 million hectares of land, were as large as European countries. …

Economic historians may not be able to agree on whether or not the Chinese economy was improving in the interwar period. But it is undeniable that the Chinese peasantry was amongst the hardest pressed in the world. Population was so numerous and investment so minimal that even China’s famously intense farming techniques were not enough to secure a standard of living much above subsistence. The depredations of the warlords and the shocks of the recession of the early 1930s, on top of periodic droughts and flooding were enough to push millions over the edge into abject penury and debt slavery. Furthermore, amidst this general sea of rural poverty, the area where the Communists established their Northern home base in Yan’an was amongst the very poorest.

Secondly, China’s agrarian poverty was understood as a political issue. … Nationalism existed by the late nineteenth century both in the city and the countryside. But after 1937 Japan’s full-scale territorial invasion provoked an unprecedented widening of nationalist sentiment and activism. In particular, the Northern Chinese peasant population, who had hitherto been notable for their relative lack of interest in modern politics, found themselves facing an existential threat. … Over the following ten years, all of the political forces in China, the Communists, the Nationalist, the collaborationist governments and the satellites operating on behalf of the Japanese sought to respond to China’s triple predicament of poverty, internal disorder and external threat. The collaborationist regimes had their own vision of stabilization. And when they got the balance of repressive violence and hands-off administration right, the Japanese and their allies were able to establish effective zones of pacification anchored by the so-called “mutual guarantee system” or Pao Chia, under which village leaders took collective responsibility for excluding communist and other resistance elements. … In 1944 the rich agricultural region between Kiangsu, Anhwei and Shantung was designated as a model province for a New China. But the balance of coercion, cooperation and inducement necessary to preserve these model zones was delicate at the best of times. In Northern China the Japanese too often resorted to the scorched earth policies of the “Three Alls” – kill all, take all, burn all. …

The Nationalist forces did not vacate the ground without a struggle. … It was the KMT who from 1937 to 1944 took the risk and paid the price of confronting the Japanese with a modern-style military resistance. But they did so without the infrastructure of legitimacy and domestic support that a modern war effort would have required. The results for the Chinese countryside were drastic. Though the nationalist had nominally committed themselves in 1937 to rent reduction and land reform, the nationalist war effort raised the depredations of warlordism to a new pitch. Press-gangs roamed the countryside drafting young men, tax rates escalated, inflation ran out of control and further devastation followed as the frontline moved inland. Most spectacularly in Henan province on 8 June 1938 the retreating NRA blasted the dikes of the Yellow river unleashing a gigantic man-made flood that drowned at least 500,000 peasants and made perhaps as many as 5 million homeless. …

The wasteland left by the retreating nationalist and rampaging Japanese was the space occupied by the Communists. Though they would later proclaim themselves the heroes of the resistance, their main strategy was not actually war-fighting but the establishment of base areas, areas of pacification and state building …. The Communists never abandoned their radical vision for the transformation of China, but through bitter experience in the early 1930s they had learned the cost of pushing the collectivization line too hard too fast. After 1935, given the tenuousness of their grip anywhere outside Yan’an the Communists did not dare advocate a radical land reform, let alone Soviet style collective farms. Mao’s preferred mode of land reform involved not the annihilation of the rich peasants but the redistribution and leveling out of property within the village. The effect was to integrate the landless and to widen the base of the middle peasantry. In less consolidated bases the Communists stuck to the line agreed with the nationalists as the basis for the United Front of 1937, prioritizing rent and debt reduction, combined with progressive taxation and minimum wages. More aggressive steps that risked reopening the question of class antagonism were only approved for those base areas that were firmly under communist control. …

This flexible system of policy anchored on a small number of secure bases allowed the communists to survive repeated Japanese efforts to wipe them out. When in 1944 the Japanese lunged once more across central China in a desperate effort to open a land corridor to Burma, the result was to deal a further devastating blow to the nationalists, while opening the door to further communist expansion. By the time of the Japanese surrender in 1945 the Communists commanded a “liberated zone” consisting of one quarter of the territory of China and one third of its population. It was now poised to launch the transformation of the Chinese countryside. On 4 May 1946, the anniversary of the day of national humiliation in 1919, the Communist party was given a new watchword: “land to the tiller”. … By September 1948 even Mao had to intervene to bridle the enthusiasm of local level cadres. Ideological rectification, land redistribution and military mobilization were fused together. Within two years 1.6 million peasants were drawn into the Red Army raising its strength from 1.2 to 2.8 million men. Whereas in Western Europe the mechanized armies of the Allies were frustrated by an immobile countryside, in China the countryside itself mobilized against the Nationalists. As Fairbank and Goldman describe it: “in 1949 in the climactic battle of the Huai-Hai region north of Nanjing, the Nationalist armored corps, which had been held in reserve as a final arbiter of warfare, found itself encircled by tank traps dug by millions of peasants mobilized by party leaders like Deng Xiaoping.” But only once the Nationalists had been driven back to Taiwan would the full force of the Communist programme make itself felt across all of China, including the South where landlordism and nationalist sympathies were most deeply rooted. … By 1957 109 million peasant households, the largest nation of peasants in the world, once famed for their independence and resistance to central power had been integrated into a collectivized Communist system.

VI

The promise of collectivization was that it would enable Mao’s regime to triple China’s investment rate and break out of decades of economic stagnation. But after 1945 the Communists had no monopoly on land reform policy. The message that a new land settlement was the answer to the developmental impasse of the interwar period was driven home no less emphatically by the great capitalist success story of postwar Asia, Japan. Plans for the redistribution of 2 million hectares of land had already been prepared during the war by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture. …. In 1945 with the energetic backing both of the US occupation authorities and the reformist Japanese socialist party, land reform was put back on the agenda. By 1950 the government had acquired and transferred 1.742 million hectares, a third of Japan’s farm land. … In Japan, and then in Taiwan too, land reform was credited with stimulating investment and helping to raise growth rates to unprecedented levels.

Japan’s extraordinary growth and China’s revolutionary transformation threw into question the experience of the other great peasant population of Asia, in India. On the face of it, the political facts seemed straight forward enough. Following the war, the British retreat was forced by the mobilization of a mass movement of huge proportions enrolling millions of Indian peasants in the nationalist Indian National Congress and the Muslim League. Not surprisingly following independence in August 1947 land reform was announced as a matter of national priority in both India and Pakistan. In India responsibility was handed down to the state level to be decided on a decentralized basis. What ensued was what one authority has described as the most ambitious program of land legislation in history, a veritable avalanche of statutes. And there were real improvements in the conditions in India’s 600,000 villages. In particular, the abolition of the intermediary layer of zamindar tax farmers established more secure tenancy and a direct relation with the new Indian state for 20 million peasant households. However, as the enthusiasm of independence wore off, a more sober assessment set in. Despite copious land reform legislation, by the end of 1970 no more than 1.2 million acres had been distributed to landless farmers, a derisory one third of one percent of India’s agricultural land. … The mid-century crisis had brought independence to the sub-continent, but unlike in China or even in Japan, it had not brought about a radical transformation of society.

The explanation for the absence of social revolution in South Asia that was most readily to hand was cultural. The American social scientist Barrington Moore argued that India’s conservative stability was due to caste and Hinduism. And it is undeniably true that the cultural conditions for revolution were very different across much of India than they were in China. Furthermore, since class differences often ran along religious lines the effect of the immiseration of the countryside in the 1930s was to exacerbate intercommunal tension and reinforce religious identities. … But to argue in reductive cultural terms that the mass of the Indian population was incapable of mounting resistance simply flies in the face of the evidence. Between 1919-1922, in the early 1930s and then again between 1937 and 1942, large masses of the population proved themselves capable of political mobilization and resistance to the British Raj. .. In the late 1960s peasant unrest resumed once again, this time against the post-colonial Indian state, with the neo-Marxist Naxalist movement spreading from West Bengal to dozens of provinces. Growing out of this revived radicalism, from the 1980s onwards historians associated with the so-called Subaltern School offered a new narrative of India’s trajectory to independence. What undercut the prospects of revolution was not religion or caste, they argued but the narrow class limits of nationalist politics. … neither the nationalist leadership of Congress nor the Muslim League ever had any interest in unleashing the full force of a peasant revolution.

Radically opposed though both these interpretations – culturalist and subaltern – are, what they have in common is that they downplay the effects of the historical conjuncture that concerns us most in this essay, namely the war. If we compare India with Yugoslavia and China, what is most striking is that in India the war had the effect of splintering the alliance between radical rural organizers, the nationalist movement and the peasantry on which a revolution driven by peasant nationalism depended. It was not that the war did not produce a political reaction in India. … But unlike in China, in India popular, anti-imperial nationalism was above all an anti-war movement. … the years after 1936 had seen an unprecedented mobilization of Indian peasants in the so-called kisan movement. … In 1939 they came out vigorously against the war. In Punjab and the Northern provinces, the British continued to recruit soldiers for the 2.5 million strong Indian Army. Peasant producers made handsome profits. But the majority of India was clearly in opposition to Churchill’s war.

But if the war mobilized and unified the anti-British forces, it could also tear them apart. In June 1941, Hitler’s invasion of Soviet Union changed the politics of India. By the end of 1941 the Indian Communists had been ordered by Moscow to throw their weight behind the Allied war effort. The left-wing activists who since the 1930s had championed the mobilization of the peasants found themselves in opposition to the mainstream of nationalist sentiment. ..With London failing to offer an acceptable path to independence and the defeat of the British Empire seemingly inevitable, on 8 August 1942 Gandhi declared that the time had come to “do or die”. … As the storm of protest unleashed in the Quit India campaign spread to the countryside, the British faced their most dramatic challenge since the mutiny in 1857. Police reports for August and September 1942 read as though they were coming from behind the German lines in the Soviet Union, or from the Japanese in Northern China. 208 police stations, 332 railway stations and 954 post offices were attacked. Thousands of telegraph lines were cut. … tens of thousands of rifles fell into the hands of Congress militants. In much of India the British lost control for weeks on end. In the Midnapur district of Bengal and in Satara in Maharshtra parallel administrations analogous to the Communist bases in Yugoslavia and Northern China emerged. In Bihar province Indian guerilla bands, known as azad dastas, self-consciously modelling themselves on the anti-Nazi partisan movement, sustained an insurgency that lasted until the end of the war.

The British reacted with massive force. 57 battalions were mobilized to repress the movement. At least 1285 protestors were killed. 3125 were wounded. But even this was not enough to quell the violence. By the middle of August the Viceroy was reduced to authorizing the RAF to strafe crowds of protestors. In total 91,836 people were arrested, 18,000 detained. India would fight its “people’s war” under the smothering repression of martial law. When the Viceroy made his usual procession to Calcutta in December 1942 he did so as if through hostile territory in an armored convoy with guards posted at every railway crossing en route. An army of 3 million men was stationed in Bengal and Bihar provinces. They saw to it that the more than 2 million victims of the Bengal famine in 1943 died largely in silence. But even a smothering blanket of press censorship could not hide the collapse of the Raj’s political legitimacy. There was no longer any doubt that once the war was over independence would come. But the disunity provoked by the war had disrupted the wide-ranging radical mobilization that up to the summer of 1941 had promised to tilt the balance within the nationalist movement decisively to the left. Quite unlike in Yugoslavia or China, in India it was the right-wing of the National Congress that emerged strengthened from the war. The Muslim League, for its part, had played a tactical game of wait and see. In the war’s aftermath the Raj was primed for communal partition, not social revolution.

VII

… The agrarian world that emerged from the crises of the 1930s and 1940s was partitioned, first into national systems by the great depression, then into ideological camps by the Cold War. In one world were the cosseted and protected agricultural systems of the rich industrialized nations, politically integrated, mechanized, with all surplus labour drained into the cities, insulated from world market pressures by impenetrable walls of protectionism. The second world of collectivized socialist agriculture was anchored in Europe on the coercive power of the Soviet state and in Asia on Mao’s China with its North Korean and North Vietnamese imitators. Finally, across the rest of postwar Asia the peasant came to stand both as the new symbol of the impoverished Third World and as a strategic actor in new arena of revolutionary and counter-insurgency warfare.’

Fascinating and informative.

It did strike as peculiar to deem industrialization in the USSR as "forced," which almost forces the unspoken conclusion that only industrialization for profit can be free, presumably because only that is natural.

The Bloodlands thesis associated with Timothy Snyder seems to entail causally equating Stalin/Communist assaults on the peasantry with German assaults, which personally I find quite dubious.

The Irish thesis that famines are an act of God---as modified with the modern exception for man-made famines caused solely by Communism by dogma and/or policy---is not addressed in this excerpt. The Bengal famine is mentioned but has no cause here and the Henan famine in 1942 isn't cited.

I don't think there is any reason to suppose a socialist revolution in india in 1940's and your implicit blaming of stalin/ USSR. It was always the liberal/ conservative strain which was strong and liberals barely won due to partition