Chartbook 293 "Nope!" or the political void at the heart of Europe's supposed safe haven - Germany after the European elections.

Meaningful and persuasive speech is essential to politics. It is what makes politics into a realm of human activity distinct from coercive violence or business transaction. Elections are the central events of democratic politics. So when a democratic leader is asked to comment on a devastating electoral defeat, as Olaf Scholz the German Chancellor was ask to do following his party’s humiliation in the European elections last Sunday, and his reaction is a truculent "Nö!” (Nope), he fails. He fails at a very fundamental level.

The European elections are not a side show. Two thirds of the German electorate turned out on June 9th. That is the same percentage of eligible voters that took part in the historic US Presidential election of 2020. That he should dismiss such a major political event as a journalistic inconvenience to which “no comment” is the appropriate answer, sums up Scholz’s fundamental failure as a democratic leader.

And let there be no mistake, the result was devastating for Scholz and for the government he leads. Right now the attention of the anglophone media is on Trump v. Biden, Macron v. Le Pen and Sunak versus himself. South Africa and Mexico get a look in. In the midst of all this democratic excitement, Germany is regarded as a safe haven. And there certainly is no risk to Germany’s government debt. If German politics continues to drift, its default setting is austerity. That may calm financial markets but given the risks ahead - add French political turmoil to Ukraine and Trump - and the void in Berlin should be deeply worrying.

Last weekend, the three parties of Olaf Scholz’s coalition garnered less than one third of the vote. Scholz’s own party, the storied Social Democrats, received less than 14 percent, their worst result in a nationwide election since the founding of the Federal Republic in 1949. The approval ratings for the Scholz-led coalition are the worst ever recorded for a German government. Three quarters of the population are dissatisfied. And this collapse in support is all the more consequential for being nationwide.

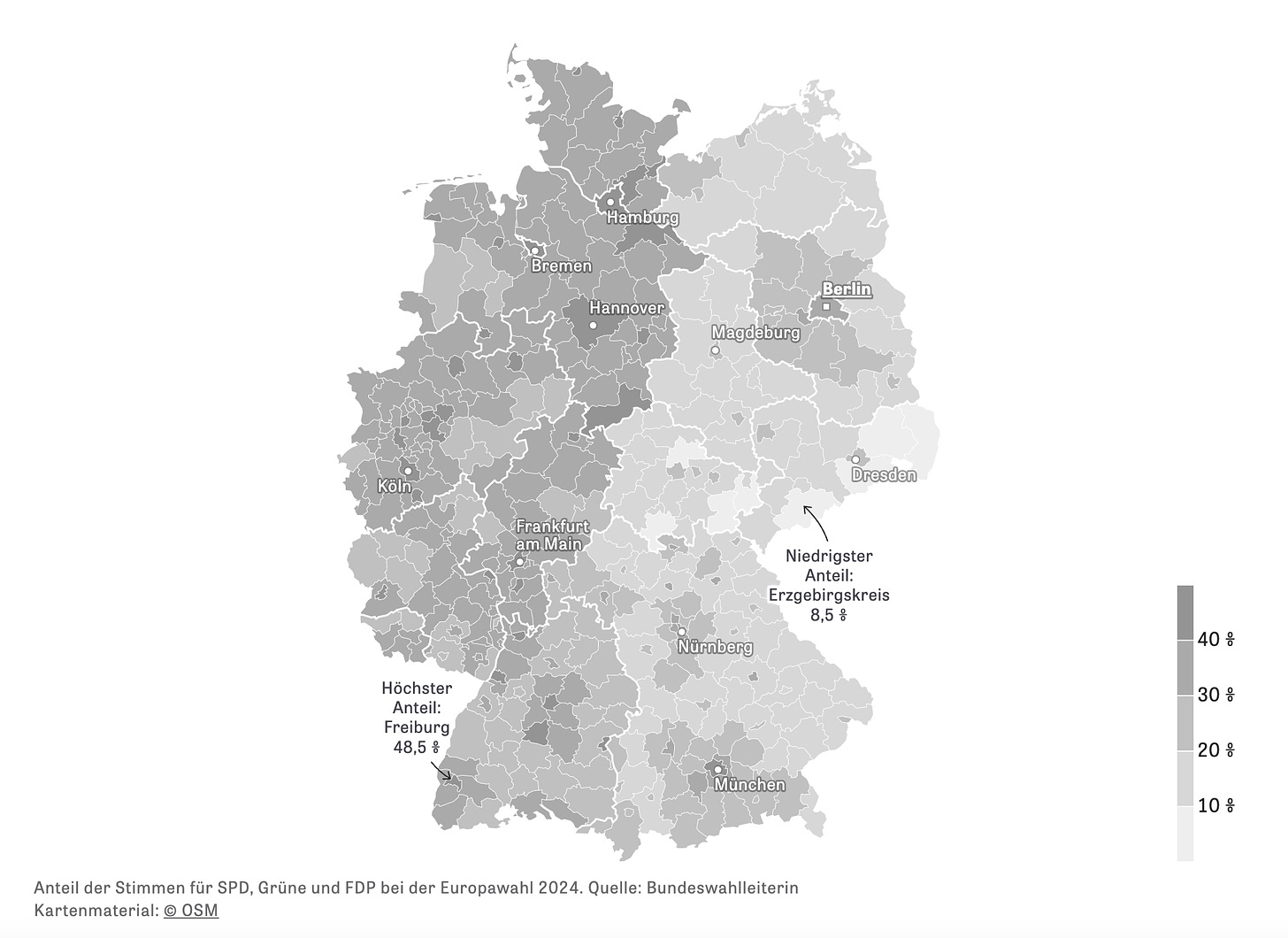

When Die Zeit, a liberal newspaper that is no enemy of the government, went looking for local districts - Germany has 400 of them - where the coalition scored a majority, they came up empty handed. To make the point they published a blank map of Germany. To avoid wasting space, I include instead a map showing the share of the vote that the coalition did achieve, the darker districts being those with larger shares.

Unsurprisingly, the coalition scores best in West Germany and came closest to a majority in Freiburg, the most solidly green of University towns. But, even in Freiburg the coalition fell short. Across large parts of the East, Scholz’s coalition hovers around the 10 percent mark, hugely outscored by the AfD and sometimes trailing behind Sahra Wagenknecht’s upstart one-woman party. Let me repeat: In parts of the East all three established parties of the German government struggle to beat a maverick party that is six months old.

We have become used to Scholz’s efforts to hide his lack of answers behind a nervous silence. But a major national election, in which he featured heavily in advertising and in which is party suffers a historic loss, is not a matter on which an elected leader can simply be silent. When the German Chancellor responds to this electoral disaster as though it were no more than an irritation, it is he, not the populists, who delegitimizes democracy.

What might be motivating this failure? Apart from Scholz’s personal limitations, two possible answers come to mind.

The first answer is that the Scholz camp believe that we have seen this movie before. In the past Scholz has proved his critics wrong. In 2019 he rose to the top of the SPD after a devastating electoral defeat in the European election - up to that point the SPD’s worst performance on record. Following a sterling performance as Finance Minister during the COVID crisis, Scholz brought the SPD back in the German elections of 2021 to win against a lack luster post-Merkel CDU. If in 2025 the CDU runs with the unappealing Friedrich Merz as their candidate, Scholz and his team may fancy their chances of pulling off another upset victory.

Going further back in time - German politics has a long memory - in 2003 Scholz was a loyal member of the team around Chancellor Gerhard Schröder when he forced through historic changes to Germany’s benefit and labour market system - the now-notorious Agenda 2010. If you talk to people in Scholz’s circle they remind you of how twenty years ago the left were up in arms about Agenda 2010. The formation of Die Linke, from which Sahra Wagenknecht’s party has now emerged, goes back to the break within the SPD at that moment. As Scholz loyalists remind you, Schroeder’s Agenda subsequently went on to become, in their words, a “pillar of Germany’s successful economic recovery”. They suggest that Olaf Scholz’s current government may also, in due course, be given the credit it deserves for pushing through the uncoupling from Russian gas, intensified efforts around decarbonization, Zeitenwende, citizenship reform etc.

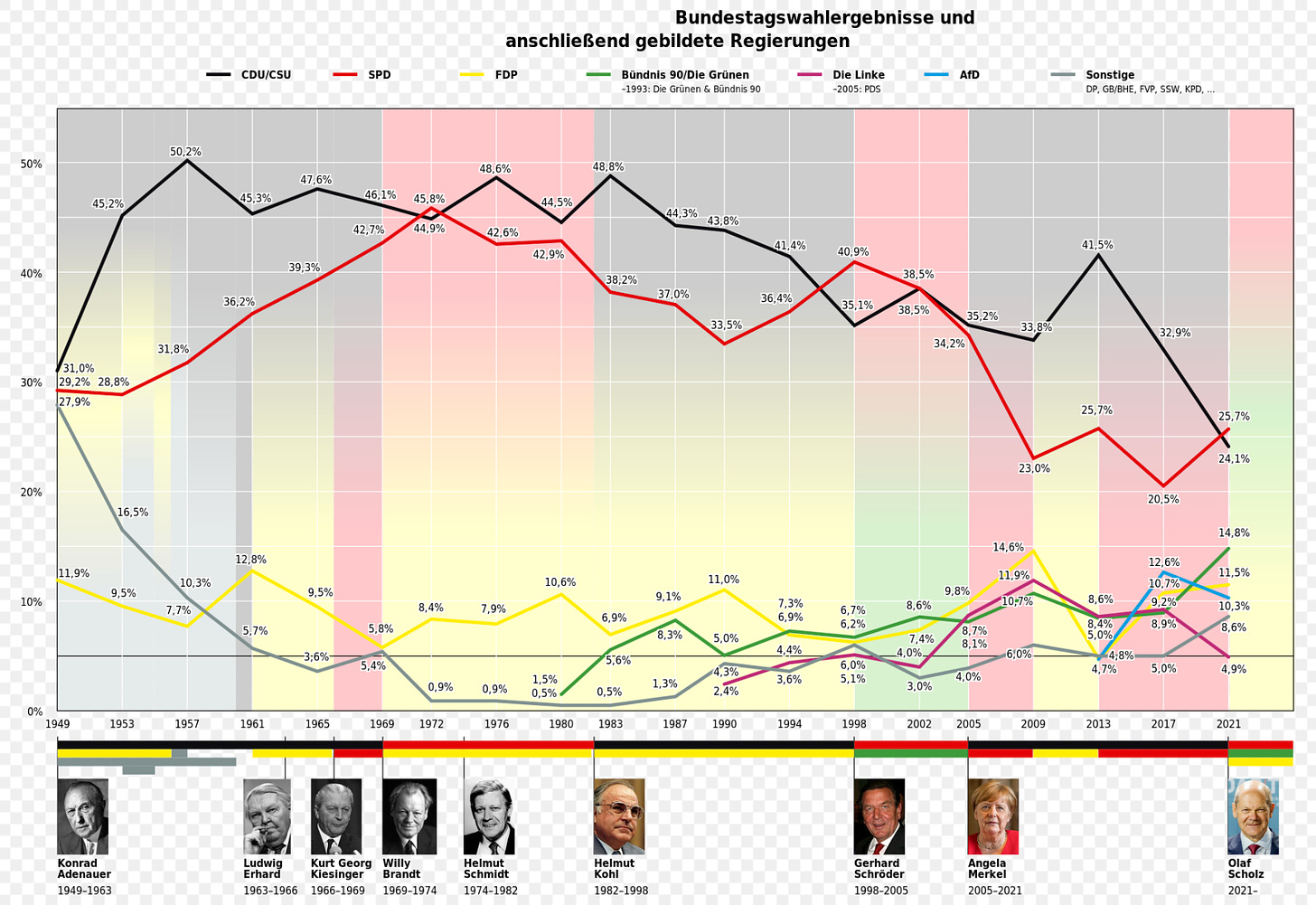

Historical analogies only take us so far. Rather than predicting another Scholz-miracle in 2024, the historical narrative may also suggest that apart from the blip in 2021 he is presiding over the latest chapter of half a century of the SPD’s decline.

But whether it predicts the future or not, understanding this history is crucial to grasping the scale of the shift that is underway in German politics.

Back in the summer of 2019, following the European election debacle, I wrote a long piece for the London Review of Books on the history of the SPD. I did not then anticipate the impact of the COVID crisis on Scholz’s fortunes or the mishandling of Merkel’s succession. I underestimated the potential of the AfD. In other words I did not have a crystal ball. But the piece still seems valuable as a reminder of what is at stake in the crisis and the structural parameters within which German democracy has operated since becoming a six-party system.

Back in 2019, this is how I summarized the significance of the SPD to Germany’s history up to the early 2000s:

“The SPD is no ordinary political party. Since its founding in 1863, from Bismarck to the First World War, through the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich, the SPD has stood for a vision of a better, more democratic and socially just Germany. Its status as a national institution is such that both Merkel and the president of Germany attended its 150th anniversary celebrations in 2013. In its long and chequered history the SPD has faced repeated challenges … Most notoriously, during the Weimar Republic, divisions between social democrats and communists helped to open the door to Hitler. In the Cold War those conflicts were stifled. The West German Communist Party was outlawed in 1956, its assets impounded and its members pursued through the courts. Unlike in Italy or France, Germany’s social democrats had no rivals on the left. When Willy Brandt took office in 1969 as the first postwar SPD chancellor, he did so in coalition with the liberal, free-market FDP.”

“The coalition governments of Brandt and Helmut Schmidt changed the face of the Federal Republic. Under the slogan of Ostpolitik, they negotiated a new relationship with Eastern Europe. Amid the affluence created by the economic miracle, they delivered on the promise of the social democratic welfare state: pensions, education and training for all, the liberalisation of abortion regulations and divorce. The generation of activists that joined the party in the 1960s and 1970s shaped it down to the recent past. But, at least on one telling, it was also in the 1970s that the SPD as its founders conceived it began to die. The industrial economy plateaued, dissolving the closed worlds of industrial work that were the SPD’s main base. Progressive politics was increasingly a preoccupation of public sector workers, salaried white collar employees and new social movements. The challenge for the SPD was to integrate its disparate interests with what remained of its traditional base.”

“Divisions in the SPD, as much as pressure from the opposition, put paid to Schmidt’s government in 1982. The FDP swapped allegiance and the Christian Democrats’ Helmut Kohl began his 16-year stint as chancellor. It was the last hurrah of the Federal Republic’s original three-party system. Ominously for the SPD, a new constituency was emerging to challenge its monopoly on the left. The technocratic centrism of Schmidt’s government had alienated the ecological and anti-nuclear movements of the 1970s. Rather than struggling to make themselves heard in the SPD, the new left formed their own party: the Greens.”

“The Greens took the youth vote and the ’68ers from the SPD, but they also poached a growing share of college-educated voters from the FDP. That narrowed the margin of the centre-right CDU-FDP coalition and opened the possibility of a new progressive alliance. The first Red-Green coalition took office in Hesse in 1985. In shabby trainers, Joschka Fischer, once a street-fighter of the hard left, was sworn in as Hesse’s environment minister. By the end of the 1980s, with the pugnacious Oskar Lafontaine, the prime minister of Saarland, in the vanguard, a new breed of SPD-led ecosocialists was on the march.”

“Germany’s Red-Green future was deferred by the collapse of the Soviet Union. The fall of the Wall scrambled the political expectations of the 1980s. Kohl revelled in the opportunity to write himself into the history books, pushing through in short order both reunification and the Maastricht Treaty, but the Greens and the SPD were caught on the wrong side of an unexpected wave of national enthusiasm. The Greens were openly sceptical about unification, aligning themselves with the movement which hoped to uphold a democratised form of socialism in a reformed GDR. Lafontaine addressed the hundreds of thousands of Germans flooding over the border as though they were foreign asylum seekers, not fellow citizens. Voters in the former East were not forgiving.”

“The prospect of reunification at first horrified the CDU’s electoral strategists. They assumed that working-class post-communists in eastern Germany would vote solidly for the SPD. The reverse was the case. Kohl’s party rapidly built new fiefdoms there, but the SPD struggled to re-establish itself even in regions like Saxony that had once been social democratic heartlands. In 1997, of the SPD’s 776,000 members, barely 26,000 were in the former East. In the 2017 Bundestag elections, the SPD came fourth in every state in the east other than Brandenburg and Berlin. The western bias is even more pronounced in the case of the Greens. It is not by accident that the AfD has chosen to position itself as Germany’s only party of climate change denial. Bashing the Greens plays well in the mining regions of the east. In large parts of the former GDR in the 1990s, as unemployment surged towards 20 per cent, the main force on the left was neither the Greens nor the SPD, but the post-communist PDS (one of the strands out of which Die Linke was later made).”

“The historic shock of 1989 reset the political clock. But … it did not stop the broad-based social and cultural modernisation of West Germany begun in the 1960s and 1970s. In 1998, after an election campaign led by a Clinton-inspired marketing team, the baby boomers of the SPD came roaring back. Kohl’s exhausted government was defeated by the SPD, led by Gerhard Schröder, the flamboyant, bon vivant prime minister of Lower Saxony, who campaigned on a platform of ‘innovation’.”

“For the first time, the Red-Green coalition headed by Schröder brought a complete change in governing parties. But how would it balance its commitments to social justice and modernisation? It delivered major changes to citizenship law, enabling dual citizenship for millions of Turkish-Germans. It continued and deepened Germany’s reckoning with its Nazi past, establishing new lieux de mémoire, such as the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in the centre of Berlin, and settling the forced labour compensation suit. Both were political high-wire acts, but at least the direction of travel was clear. The economic and financial legacies of reunification posed far more difficult choices. At its peak, in 2005, German unemployment exceeded five million, or 12 per cent of the workforce.”

“Lafontaine as finance minister wanted Germany to respond with a co-ordinated Keynesian programme of Europe-wide reflation. But he crashed out of the government within months of taking office. Schröder was only too pleased to replace his left-wing rival with Hans Eichel, a tough austerian determined to prioritise fiscal sustainability over work creation. … Schröder had already begun articulating a more stripped down vision of Germany’s capacious welfare state during his time as prime minister of Lower Saxony.* In 1999 he wrote a Third Way-style manifesto with Tony Blair. It was taken rather more seriously in Berlin than it was in London and provoked howls of indignation from SPD members. But though Schröder may have given it the green light, the decisive push for Agenda 2010, as Anke Hassel and Christof Schiller showed in Der Fall Hartz IV (2010), came from local government and the insurance and labour market agencies struggling to cope with crisis levels of unemployment.”

It was at this point that Olaf Scholz enters the story as the General Secretary of the Party who became famous as the Scholz-o-mat for his robotic repetition of Schroeder’s new party line. The impact on the SPD itself was traumatic:

“In reaction to the neoliberal turn of the Red-Green government, the German left split once again. Amid the protests of 2004-5, as SPD members returned their membership cards en masse, Lafontaine sensed his chance for a comeback. When Schröder called snap elections in 2005, Lafontaine placed himself at the head of the anti-Hartz IV mobilisation and arranged a shotgun wedding with the post-communists of the PDS. The result, in 2007, was Die Linke. With its solid base in the east and highly mobilised constituency in the west, the new party vaulted into the Bundestag and once again changed the coalition arithmetic. At the federal level, a progressive government now required a three-party coalition of the SPD, the Greens and Die Linke. That was not impossible. Both in 2005 and 2013 the majority was there for the taking. But the divisions over Agenda 2010, the legacies of the GDR and Die Linke’s ingrained hostility to Nato went too deep. The SPD and Die Linke could never come to terms.

The fissuring of the German left after Agenda 2010 opened the door to the CDU’s recovery of power. Though Die Linke and Merkel are radically different expressions of post-reunification politics, they condition each other. Despite her formidable reputation, Merkel is not a successful electoral campaigner. In 2005, at the height of the turmoil and indignation stirred up by Agenda 2010, she managed only to inch the SPD out, 35.2 to 34.2 per cent. Her brand of neoliberalism stirred anxiety among CDU voters as much as Schröder’s did on the left. Only once, in 2009, did she win a vote share large enough to enable a centre-right coalition with the FDP. For three of her four governments, Merkel has relied on a grand coalition with the SPD. The impact on the SPD has been deeply ambiguous. On the one hand, except for the interlude of 2009-13, the SPD has been in government in Berlin for 21 years continuously. On the other hand the loss of identity, already visible under Schröder, has been ever more pronounced.” (for more go back to the original LRB article)

Olaf Scholz’s leadership is the quintessential product of this historic attenuation of the SPD as a distinctive political force. And this is the second explanation for “Nope!”

The reason why Scholz does not want to answer questions about his party’s catastrophic electoral performance may be that the SPD has neither a program nor a distinctive and powerful social constituency for which to speak.

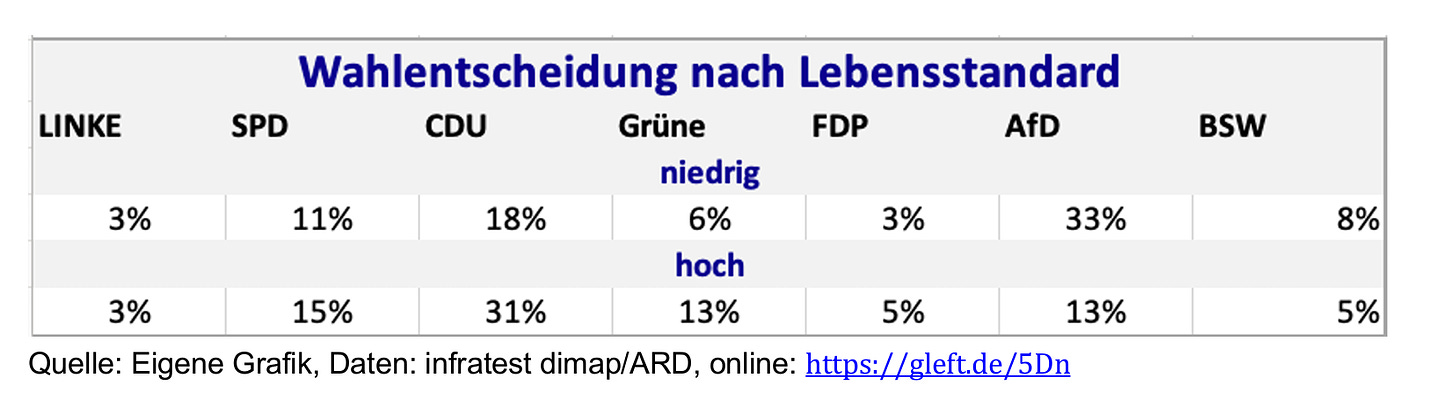

When challenged from the left, especially from the Green side, Scholz’s spokespeople will routinely evoke “ordinary Germans who struggle to pay bills” for whom they claim to speak. This would, of course, be the traditional working-class constituency long organized and mobilized by the Social Democrats. But how far can the SPD actually claim to speak for those Germans today?

One problem with this thesis is that it was the Schroeder-Scholz wing of the SPD that actually pushed through the Harz IV changes in 2004, which dramatically increased precarity and inequality in Germany.

And even at the banal level of polling it is not obvious how the Chancellor’s party can still claim to speak for hard-up Germans. Certainly it is true that within the traffic light coalition of SPD (Red), Greens and FDP (Yellow), the SPD is the most demotic. But that is not saying much. Germans who feel well off are twice as likely to vote Green or FDP than those feeling that they are doing badly. But the SPD too scores 36 percent better amongst Germans who judge themselves to be living well as opposed to those who feel hard-up. The parties whose support tilts the other way are in the opposition: Wagenknecht’s group and the AfD. Support for the AfD is two and a half times larger amongst Germans who judged themselves to be hard up than amongst those who consider themselves well off.

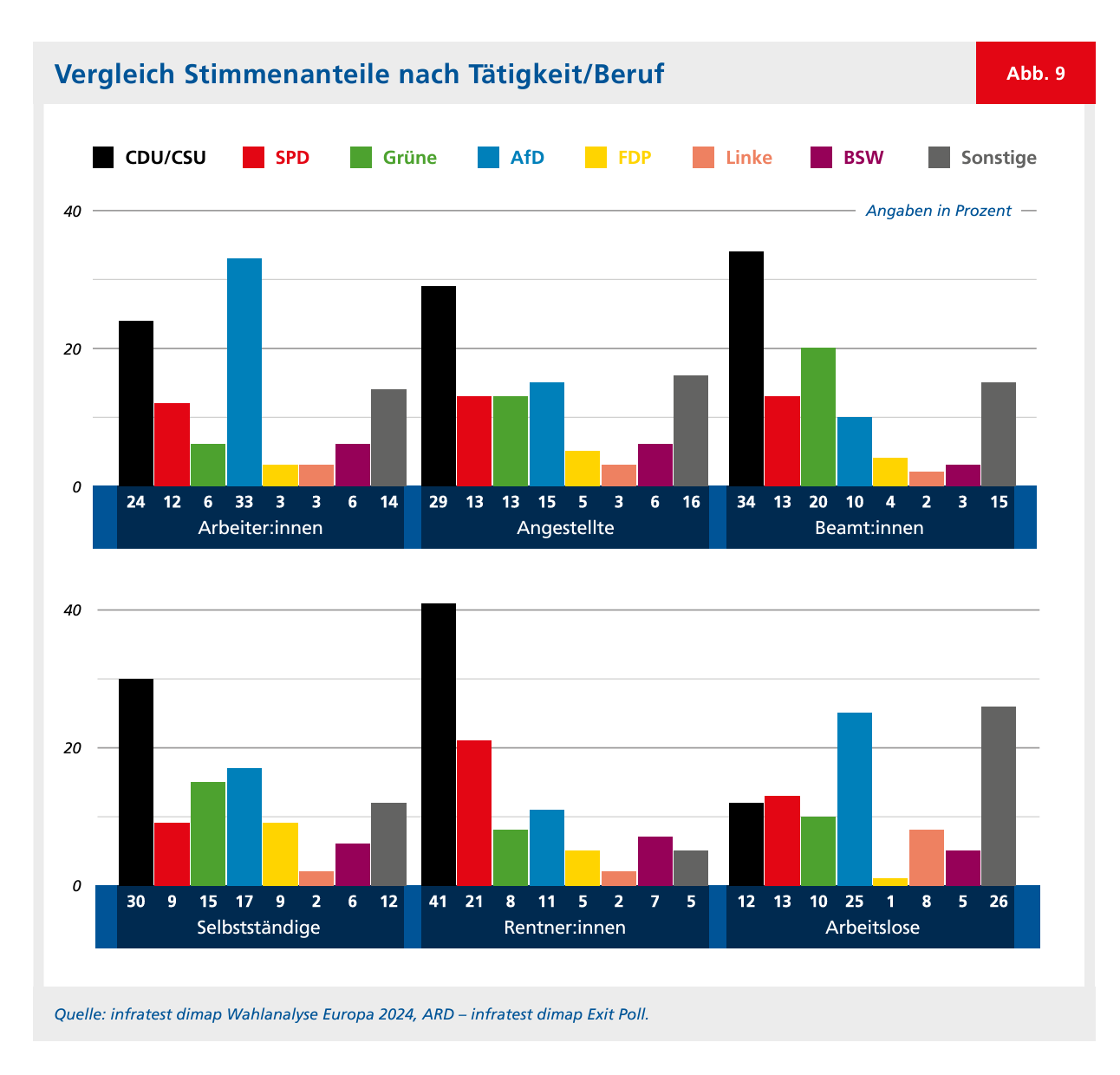

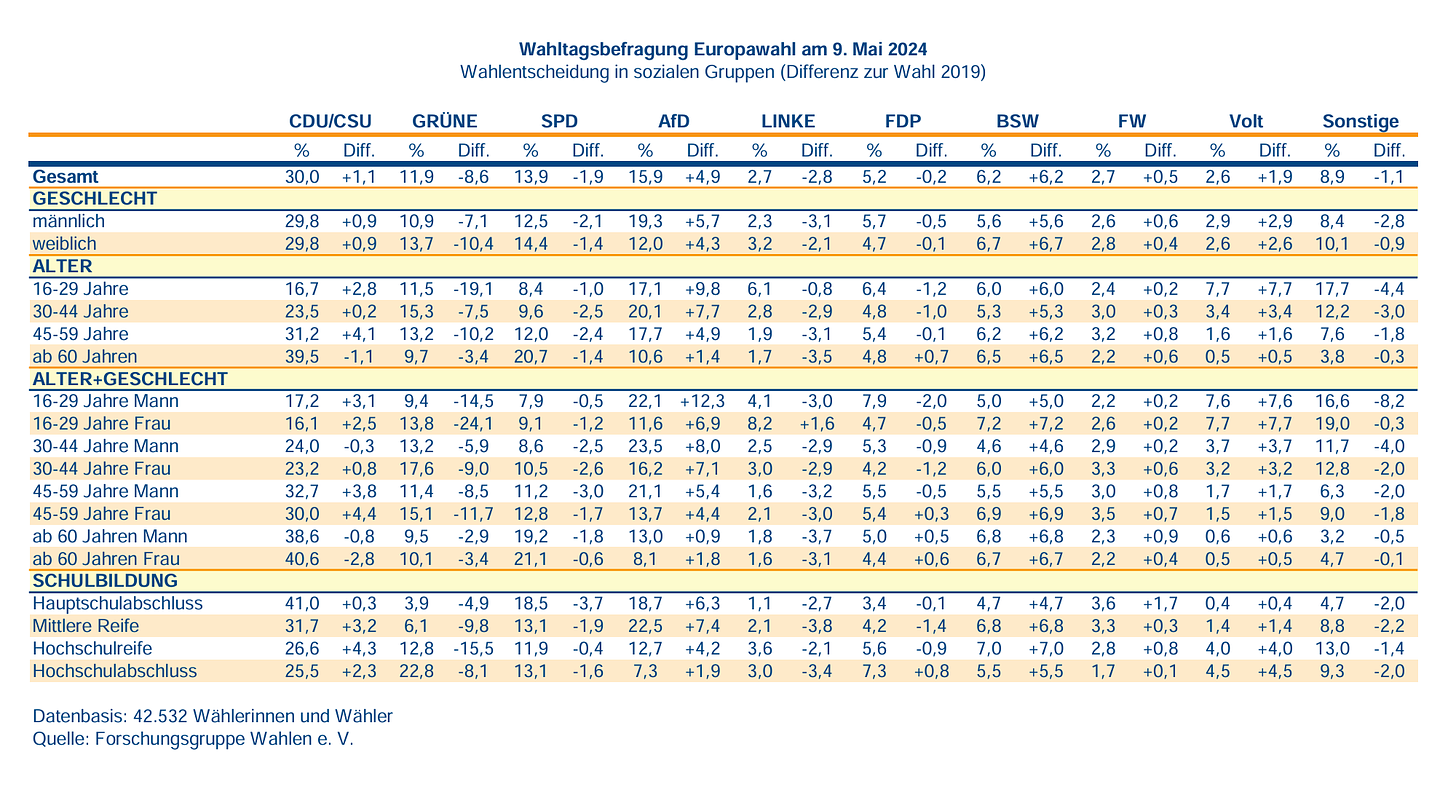

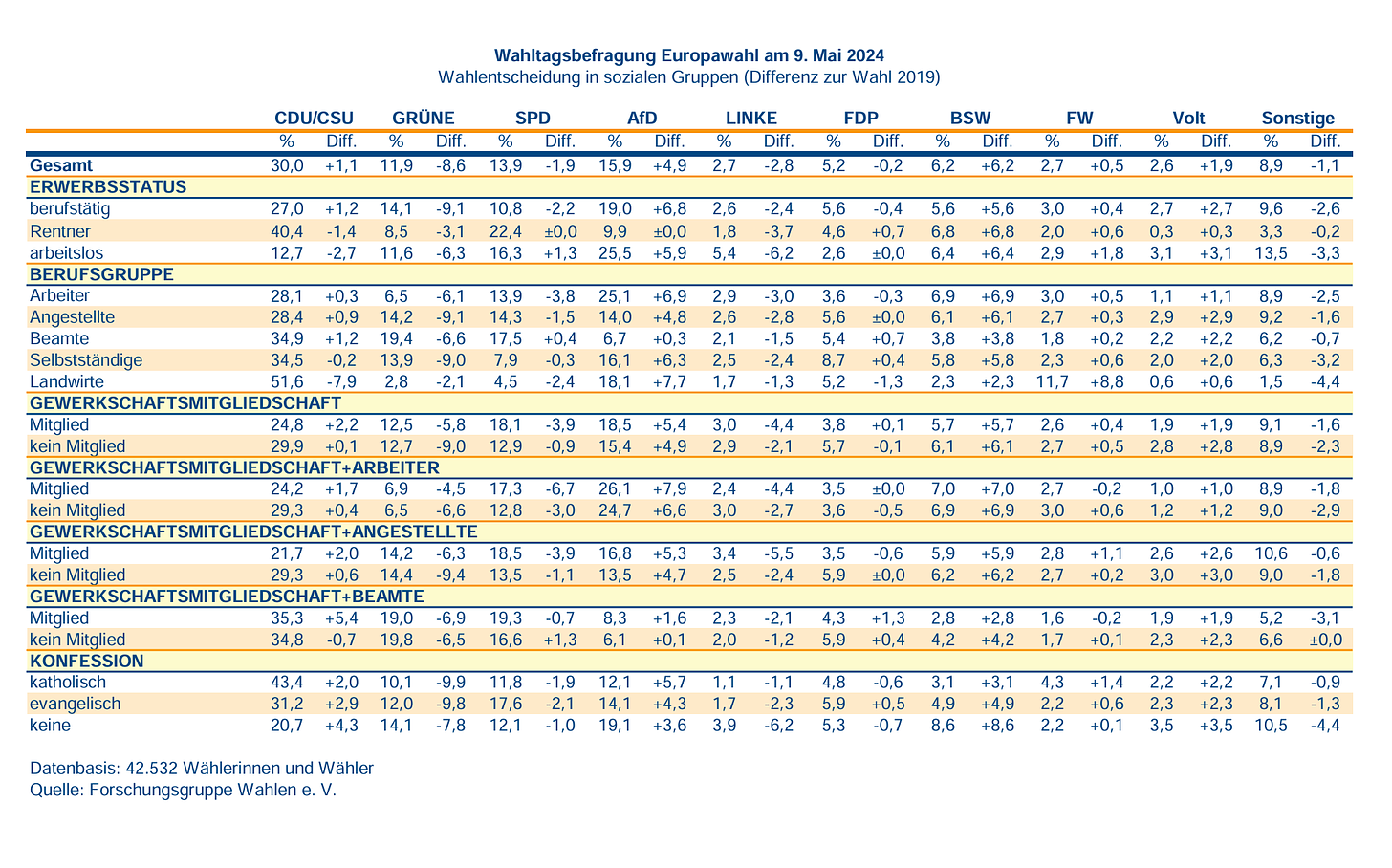

The same result emerges if we classify voters not by standard of living but by social position. The AfD is overwhelmingly the most popular party amongst the dwindling group of Germans who are either classified as “workers” (Arbeiter) or choose to identify themselves that way. The AfD also outscores the SPD two to one amongst the unemployed (Arbeitslos). Support for the SPD is stronger amongst civil servants (Beamte) and salaried employees (Angestellte). If the SPD has any distinct social constituency at all, it is left-wing pensioners (Renter). But pensions are hardly a core Scholz constituency either. The CDU outscores the SPD in that group by two to one.

Source: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

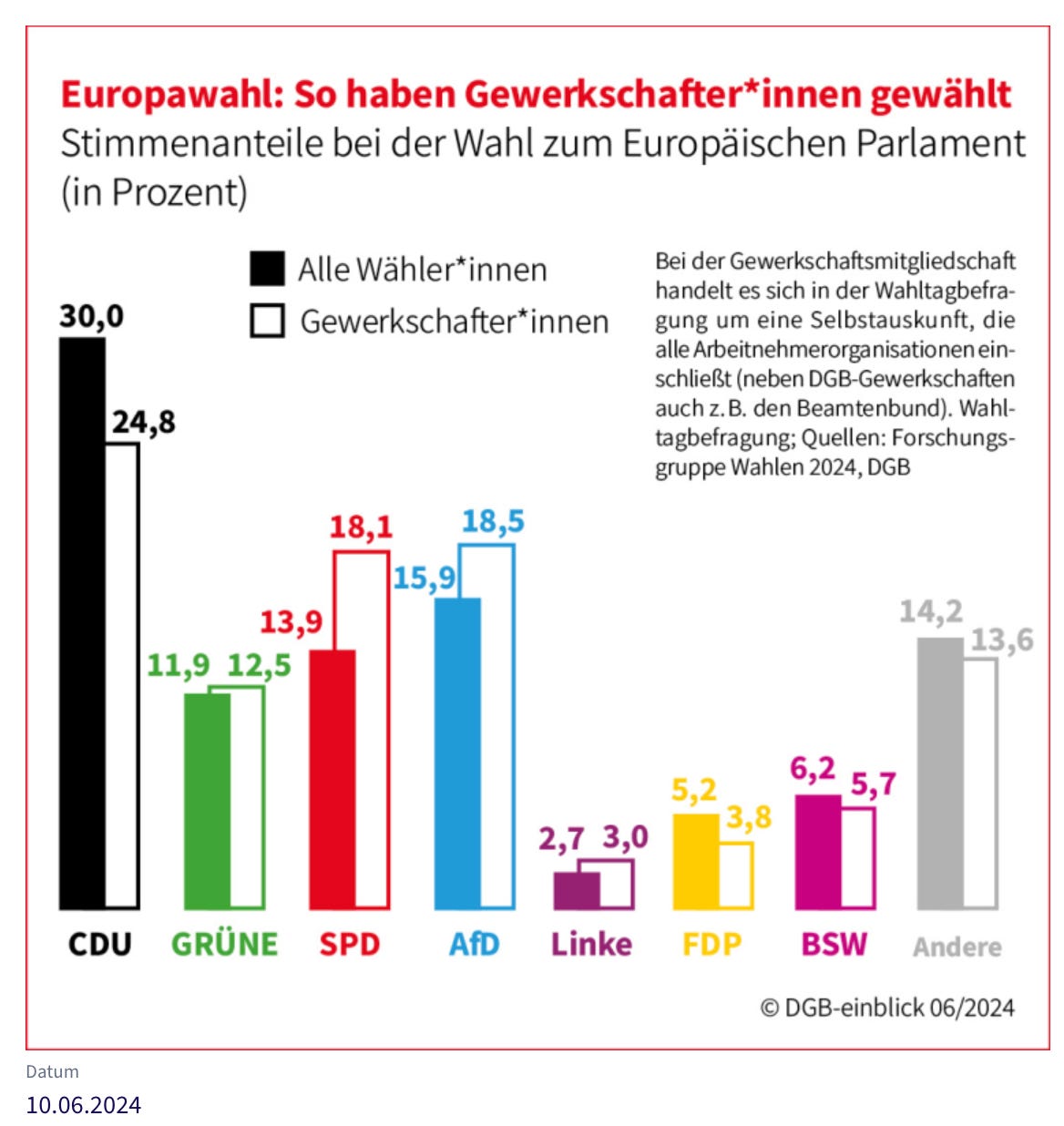

After the election the German trade-union movement published some encouraging data, which suggested that voter who are trade union members tend to vote rather less for the AfD than would be expected, allowing for social class, and rather more for the SPD. In the graphic below the solid bars are all voters and the bar behind is for unionized voters. 18.1 percent of unionized Germans voted for the SPD as opposed to 13.9 percent in the general electorate. 18.5 of unionized voters supported the AfD.

You might think that the fact that the a party suspected of sympathies for National Socialism outscores the SPD amongst trade unionist would be seen as a disaster, but in light of the results on Sunday it is actually comforting that the right-wing margin of victory is slim. If you dig deeper into the data on unionization rates and political attitudes the results are, however, less reassuring.

The most comprehensive data pack on the election published by any of the parties is that from the CDU’s Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. They compiled not just exit polls but large-scale polling done ahead of the vote that provide richer information on the electorate.

This contains more worrying news for the SPD. The weakness of the SPD amongst young people is dramatic. Amongst young German men, the AfD is by a large margin the most popular party, gaining almost three times more votes than the SPD. But, remarkably, even amongst young women the SPD trails the AfD.

But it is when we get to data on unionized voters that the pre-election surveys are truly grim. If you compare the overall rate of support for the AfD amongst working-class people (33%) with the rate of support amongst unionized workers (18.5%) you might conclude that unionization helps to bring AfD support down. But this assumes that the two groups of people are the same, but for their union cards. That is a dangerous assumption to make. If we dig into the pre-election surveys and look at unionized voters who are also classified as workers, as opposed to unionized white-collar voters or civil servants, we see that though unionization is associated with increased support for the SPD, 18.1 v. 12.9%, the same is true on the right-wing. Amongst workers favoring the AfD, unionization is actually associated with increased support for the extreme right-wing party - 26.1 v. 24.7 percent. The lower level of support for the AfD across unionized workers thus, most likely reflects the fact that the unions now organize large numbers of salaried and civil servant members who vote for the AfD in much smaller numbers.

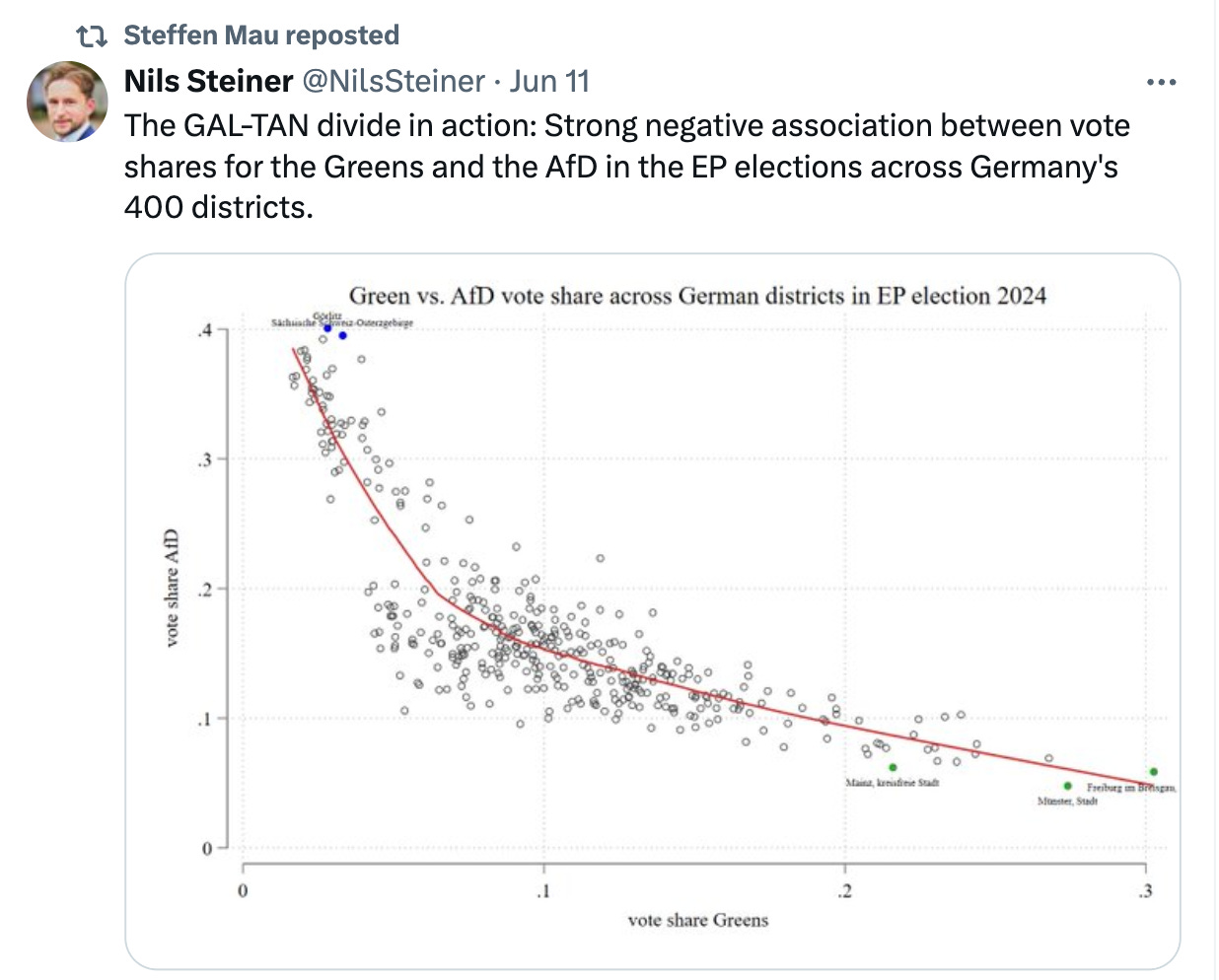

It would seem that the real opposition in German society and political preferences is not between the “old” labour movement and the AfD. The real juxtaposition is between the AfD and the Greens.

In the mass protests organized against the AfD in the run-up to the elections, it was figures associated with the Green party that often took the lead, though in the heartlands of the AfD in the East, they have virtually no presence.

Speaking to one of the leading figures in the German trade union movement this week, he was thinking the unthinkable. The party doesn’t mobilize votes. It has no special claim to represent working people. It doesn’t lead in opposition to the AfD. If the government’s agenda is going in any case to be set by the Greens, why not merge with them, as in the Netherlands?

Scholz and his team may still prove their critics wrong. They may do better than feared in 2024. But it is a bet at very long odds and that question hangs in the air as it has done at least since 2019: What is the SPD for?

Don't kid yourself. The elites in germany and elsewhere in europe consider democracy far too important to be left to the whims of the voters.

Apologies for generalising, but all the malaise in European democracies “makes sense” if we acknowledge that there is a high level of elite preselection that ends up offering candidates whose competence lies in securing preselection, not governing well.

This applies also (and especially) to the EU which in turn sees fit to intervene in national level politics. So the elites have a grip on power and elections no longer matter, only preselection matters.