Chartbook 292 Less Green - the shifting political balance in Europe and Germany after the elections.

After the election results in India, South Africa and Mexico, now a large part of the European electorate has delivered a shock to the governing agenda of Europe as well.

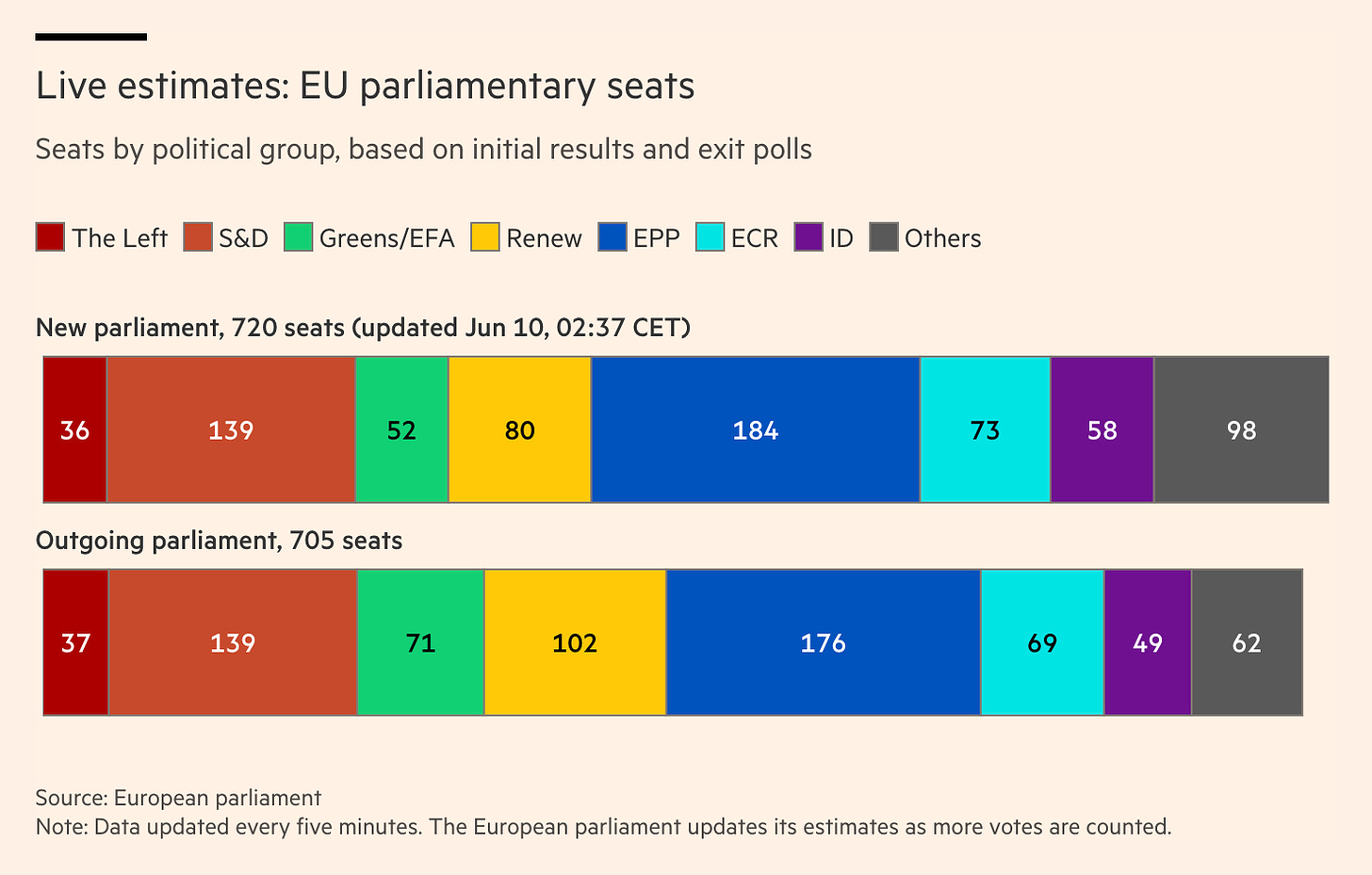

Looking at the Europe-wide result, you might think that talk of a “shock” is exaggerated. The overall balance in the parliament has not shifted much. At the European level, the social democrats and the left remain stable. The dominant EPP center-right grouping increased its haul of seats. Ursula von der Leyen has a good chance of being reconfirmed as Commission President.

Source: FT

But this image of continuity is deceptive. The elections have tilted the European political balance against the green agenda which has served as an important reference point for politics in Brussels for the last five years.

If the ECFR was correct back in January in claiming that two complexes of issues would dominate this election - migration-security versus green-climate - then the 2024 results show that the right-wing anti-migrant-security agenda has a stronger dynamic than the right-wing migration-security team. I phrase it this way because there isn’t much direct competition between the two sides. The far-right and the progressive-green parties do not compete for the same voters. But the balance between these two blocs matters, because they sway the course taken by centrist parties - Christian Democrats and Social Democrats.

Even if Ursula von der Leyen succeeds in her bid for a second term as Commission President, she will not be pursuing the full-throated green-forward policy that launched the Green Deal in 2019 and Next Gen EU in 2020. This does not mean that the EU will adopt a climate-skeptical position. But priorities will shift and difficult trade-offs will be avoided. There is a groundswell of opinion in Europe that is preoccupied with the cost of living, wants to keep its internal combustion-engined cars and sympathizes with farmers in their opposition to green regulation. That grouping will now have a much louder voice.

This is all the more likely given the results in Germany and France, the two largest states in the Union. Despite their differences over atomic power, the green agenda of the EU in the last five years was supported by both Germany and France. In 2019 Ursula von der Leyen was a Merkel nominee with French approval who cooperated with Dutch social democrats. In 2021 Germany elected a SPD-Green-FDP administration with a climate agenda. Macron’s reelection in 2022 bolstered the idea of a green coalition against populism. Faced with socio-economic “long COVID”, long-running concerns about migration, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and impact of energy price shock, that coalition has suffered a severe set back.

In France the right-wing victory was so dramatic that President Macron decided to call snap parliamentary elections. Let that sink in. European elections matter enough to fell a French government (i.e. a prime minister and their parliamentary majority, not the Presidency which Macron retains until 2027). That is in itself remarkable.

Macron may be gambling that he can shock French voters into rallying once again against the far right. Or he may hope that allowing the French far-right to take on some of the painful business of governing, is the best way to weaken them ahead of the Presidential election in 2027. The best explanation of his thinking that I have read is this thread by Georgina Wright. Either way, France, the #2 power in Europe, is now in political turmoil and the likelihood is that its national politics will shift decisively to the right.

In Germany there is no talk of immediate elections. The reaction to Macron’s snap decision was one of disbelief. It is hard to imagine anyone in Berlin uttering Macron’s lines:

“France needs a clear majority in serenity and harmony. To be French, at heart, is about choosing to write history, not being driven by it.”

But for all that, there is no escaping the devastating rebuke that the results in Germany have delivered to the governing coalition. For the SPD, which has had precious little to offer on Europe, the result was even worse than the shock defeat of 2019. Chancellor Scholz’s party fell from 15.8 to 13.9 percent. The Greens, whose dramatic 20 percent score in 2019 set the tone not just for Germany but for Brussels as a whole, plunged to 11.9 percent. The right-wing AfD, which is both euroskeptical and climate skeptical and whose leading EU candidate had to be sidelined after he made excuses for Hitler’s SS, increased its vote share from 11 to 15.9 percent, coming second overall. The CDU/CSU scored the same 30 percent that it achieved under Angela Merkel. The most striking thing is its failure to capitalize on Scholz’s weakness. Meanwhile, Sahra Wagenknecht’s personal party that broke away from Die Linke, scored 6.2 percent from a standing start, which confirms her current polling and puts her ahead of the FDP, which provides Germany’s Finance Minister.

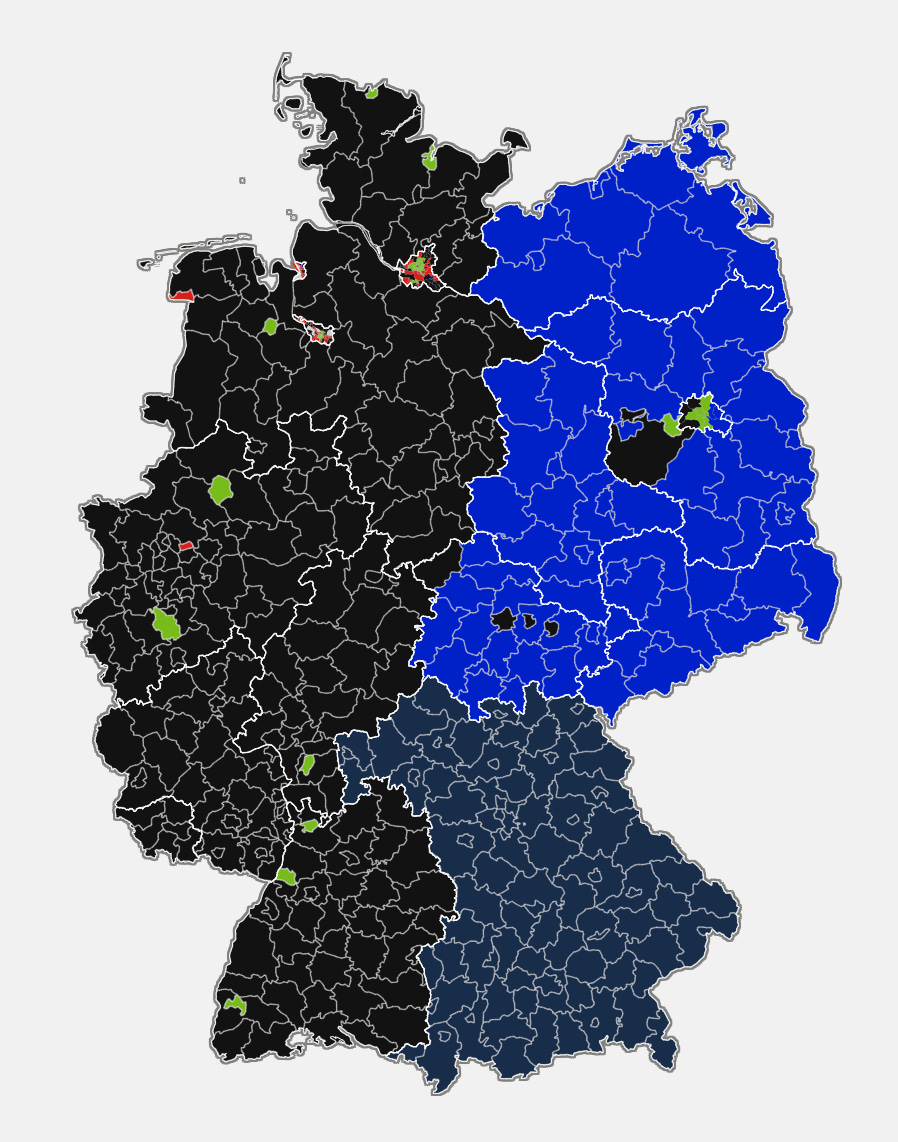

A map of the leading party in each region of Germany dramatizes the results. Black is the opposition CDU/CSU. It leads in most of the former West Germany. Blue is for the opposition far-right AfD. It leads in the East. Only in urban areas do the governing SPD or the Greens heads the polls. Bavaria is shaded blue-black because though the CSU there commands 39 percent support, the party in second place, unusually for a West German state, is the AfD. In Bavaria the CDU and AfD together have a solid absolute majority. Bavaria shares the distinction of a right-wing majority with Saxony, Sachsen Anhalt and Thuringia. In the rest of Germany though the right-wing parties are the strongest, they still fall short of 50 percent.

Source: This and other data below are from ARD

Across the former East Germany, the far-right AfD at around 30 percent is now the strongest force. On the left, Sahra Wagenknecht’s new party, formed by a breakaway from Die Linke, scored almost 13 percent in Saxony, 13.8 percent in Brandenburg and 15 percent in Thuringia, making it very difficult to assemble a coalition to block the AfD, without involving Wagenknecht.

These are the European elections, not a national vote. They are often an occasion for protest voting. But in the past this has tended to favor the Greens, who have the most pro-European electorate. Now, at the national level, the governing coalition of SPD, Greens and FDP are reduced to a mere 31 percent of the vote. This begs the question of legitimacy. In Bavaria the parties of the national government didn’t manage 25 percent. In Saxony SPD, Greens and FdP together barely scraped 15 percent, just ahead of Wagenknecht.

There is little mystery as to what is driving this collapse in support for the governing coalition.

Handling the Ukraine war, the surge in prices and the need to pass contentious green legislation would have required skilled and charismatic leadership. Chancellor Scholz of the SPD has failed to deliver this. The Greens shot themselves in the foot with the trench warfare over the law regulating domestic heating in 2023. The FDP has become a disruptive spoiler in the three-way coalition.

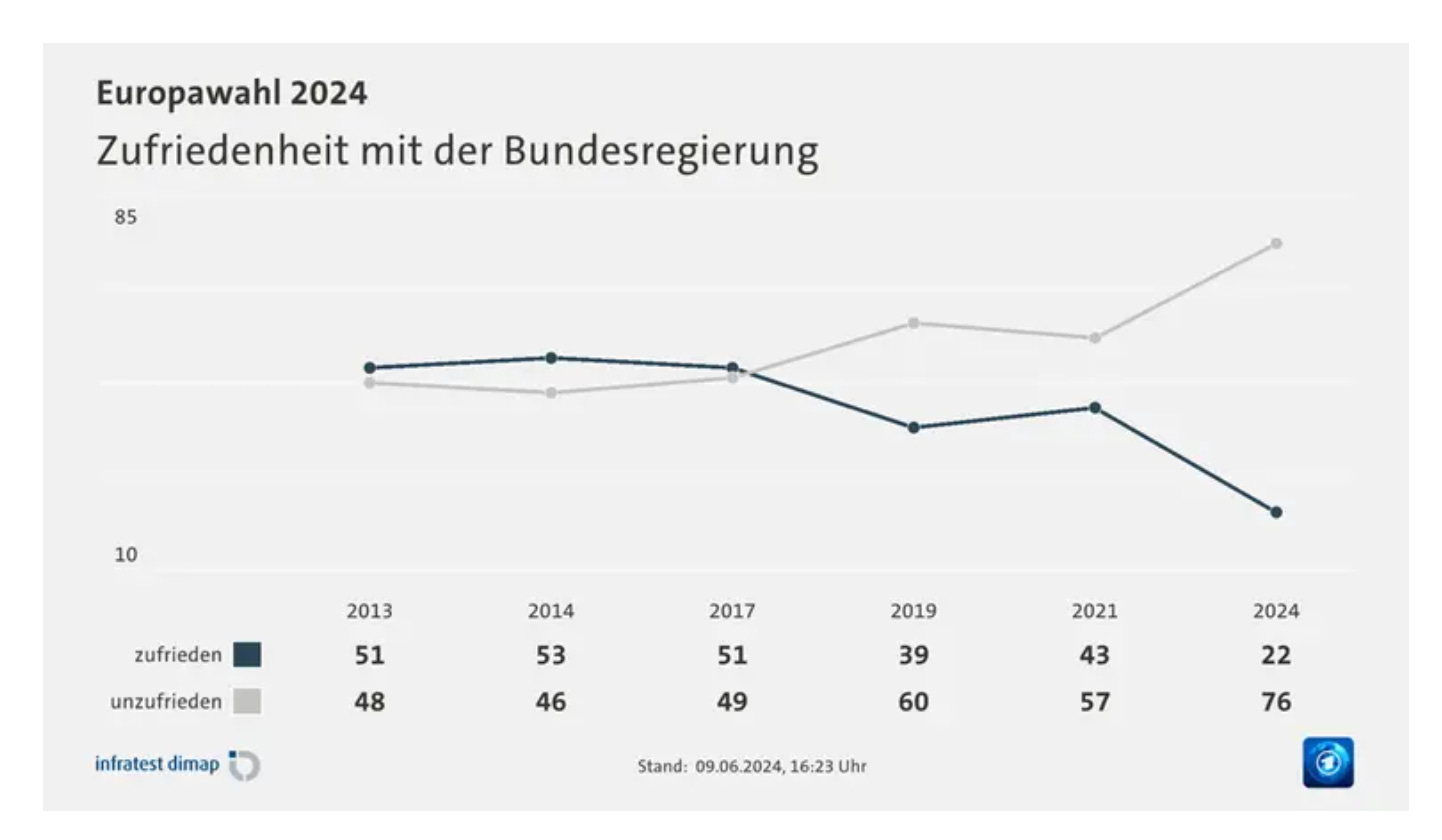

Overall satisfaction with the German government (Zufriedenheit mit der Bundesregierung) is at historic lows. If anyone knows of an earlier period when a German government had a satisfaction score of 22 percent, I would love to see the data. Even in the disaffected late 1990s, satisfaction levels were at 30 percent.

Without clear and effective communication or leadership, the agenda has been seized by concerns for security, economic pessimism and xenophobia. The chart below shows responses to the question: Which issues was most important for your decision in voting? The top line (dark blue) is Frieden i.e. peace. In 2019 climate/environment (Klima/Umwelt) topped peace. In 2024 climate had fallen into third place behind Zuwanderung i.e. migration (in grey).

2019 was an election held in good times, before COVID and the war. This allowed climate to come to the fore as the main issue. For many German voters the world today appears a much bleaker place. Climate remains a concern but it is no longer the dominating priority.

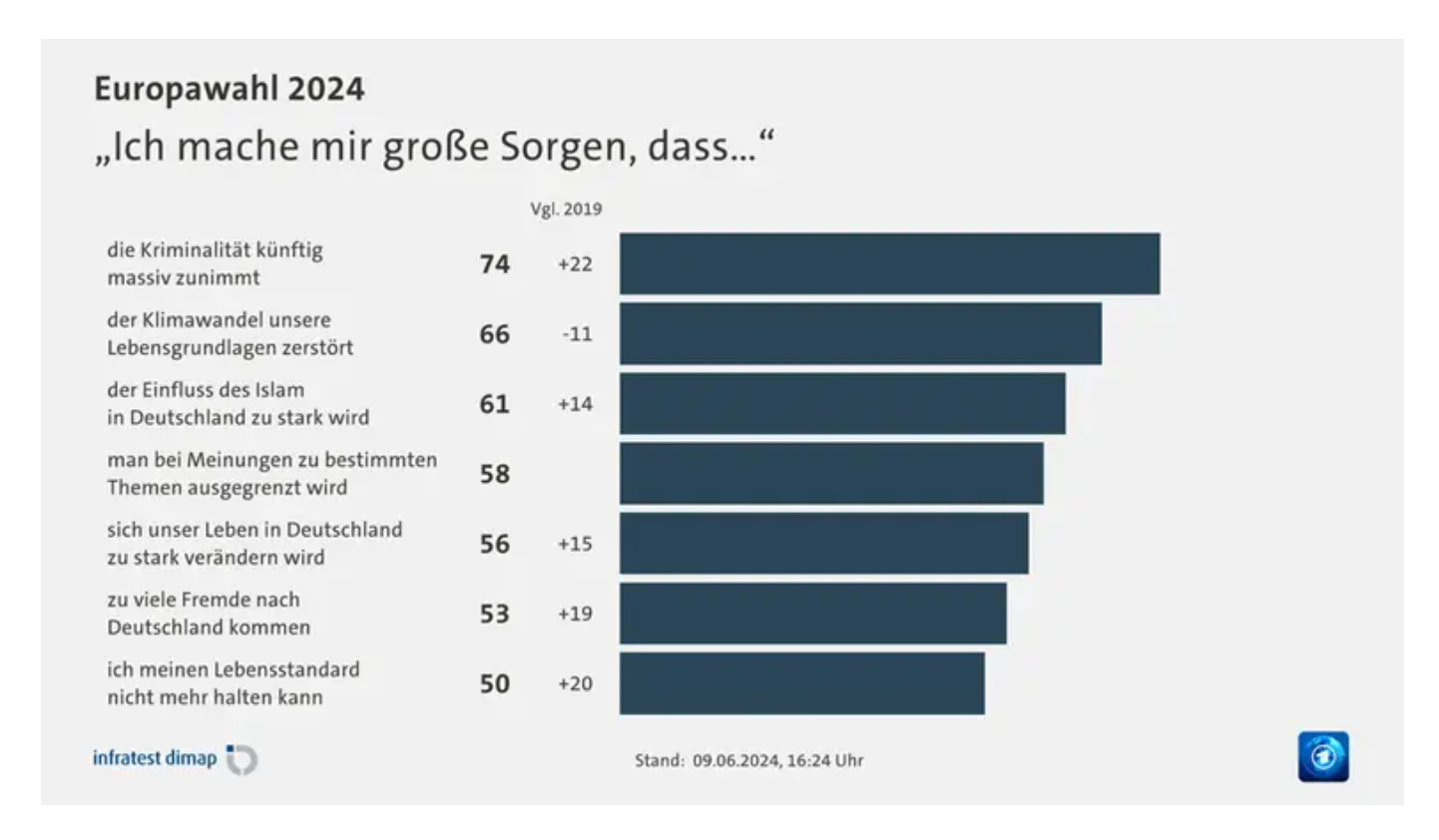

When Germans are asked what are their greatest worries (Sorgen), the leading answer with 74 percent, is a surge in crime (Kriminalitaet). This is up 22 points since 2019. Climate (Klimawandel) comes in second, but this is down 11 points relative to 2019. 61 percent mentioned the rising influence of Islam (Einfluss des Islams), up 14 points. Fear of changes to German life and “too many foreigners” also scored high. Concerns about being able to hold their standards of living (Lebensstandard) were expressed by 50 percent of voters, up 20 percent compared to the relatively complacent result in 2019.

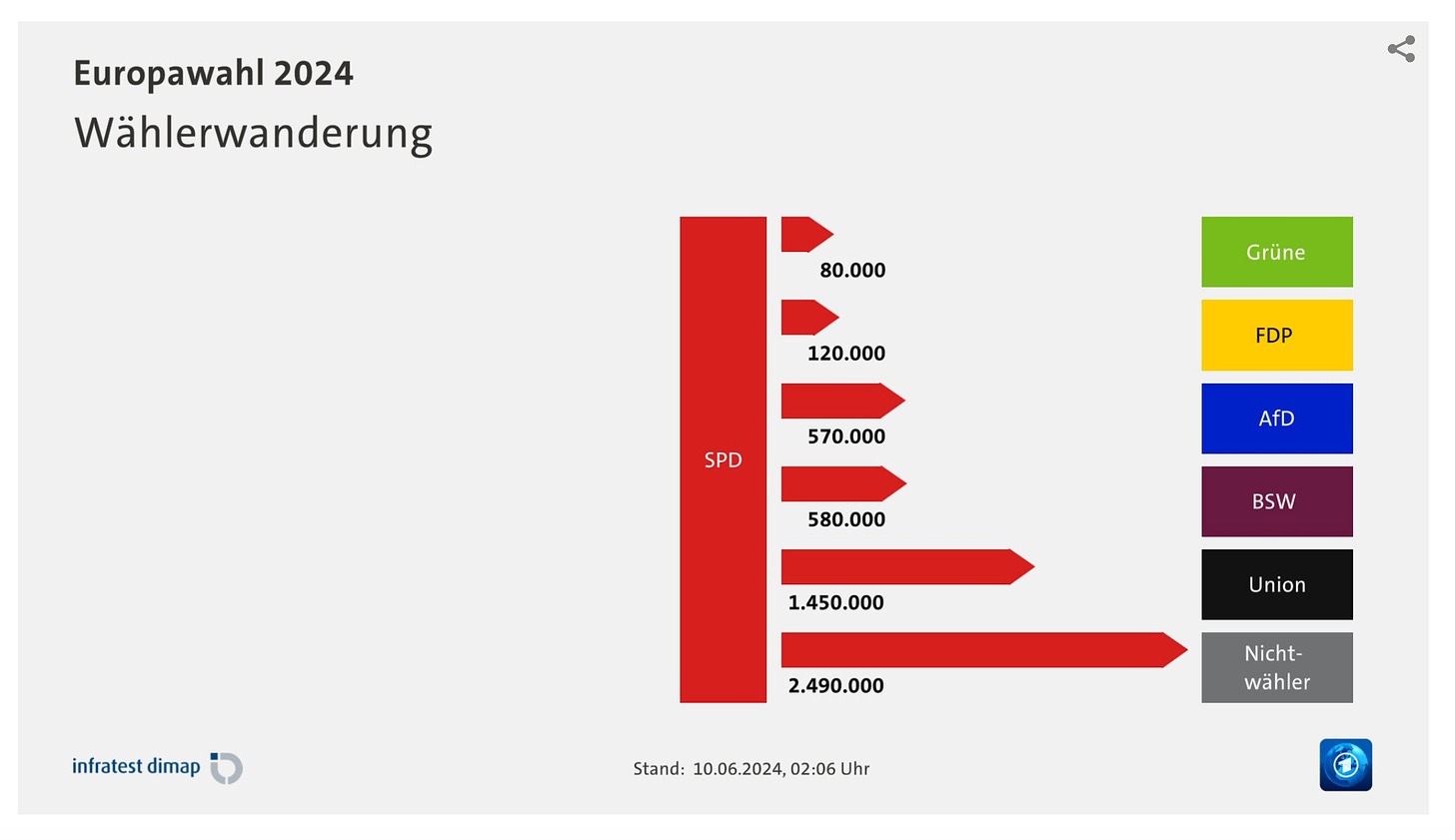

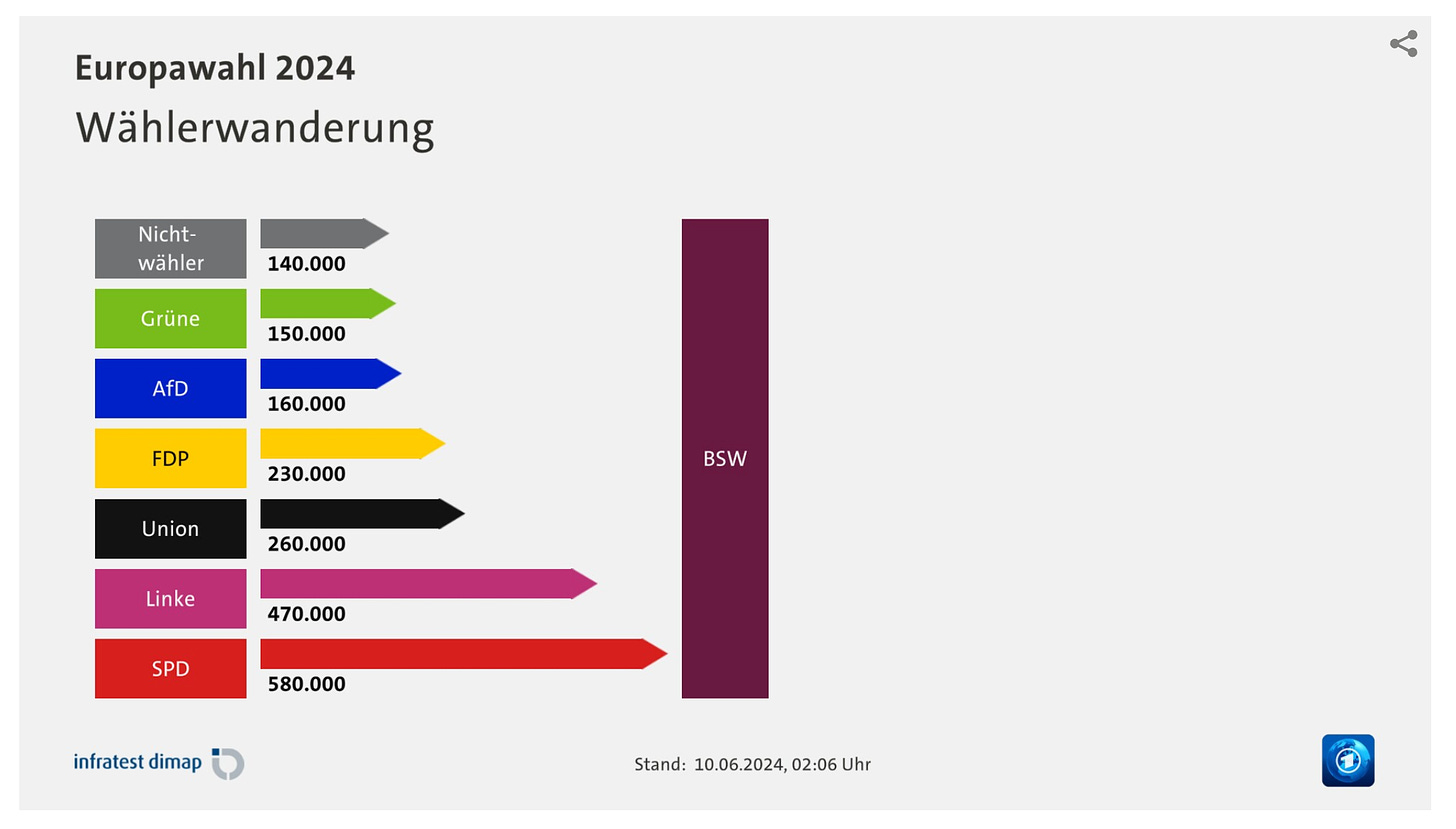

Many progressives voters, turned off by the botched coalition agenda, simply did not turn out to vote. As the graphic below shows, huge numbers of people who voted for Olaf Scholz and the SPD in the general election of 2021, when they scored 25.7 percent, did not turn out. Almost 1.5 million shifted to the CDU and a million shifted to Wagenknecht and the AfD.

Wählerwanderung = “voter migration”

The FDP gained votes within the coalition presumably for its insistence on retaining the internal combustion engine and freezing taxes. But relative to their excellent result in 2021, the liberals drained votes to the AfD, the CDU and abstentions.

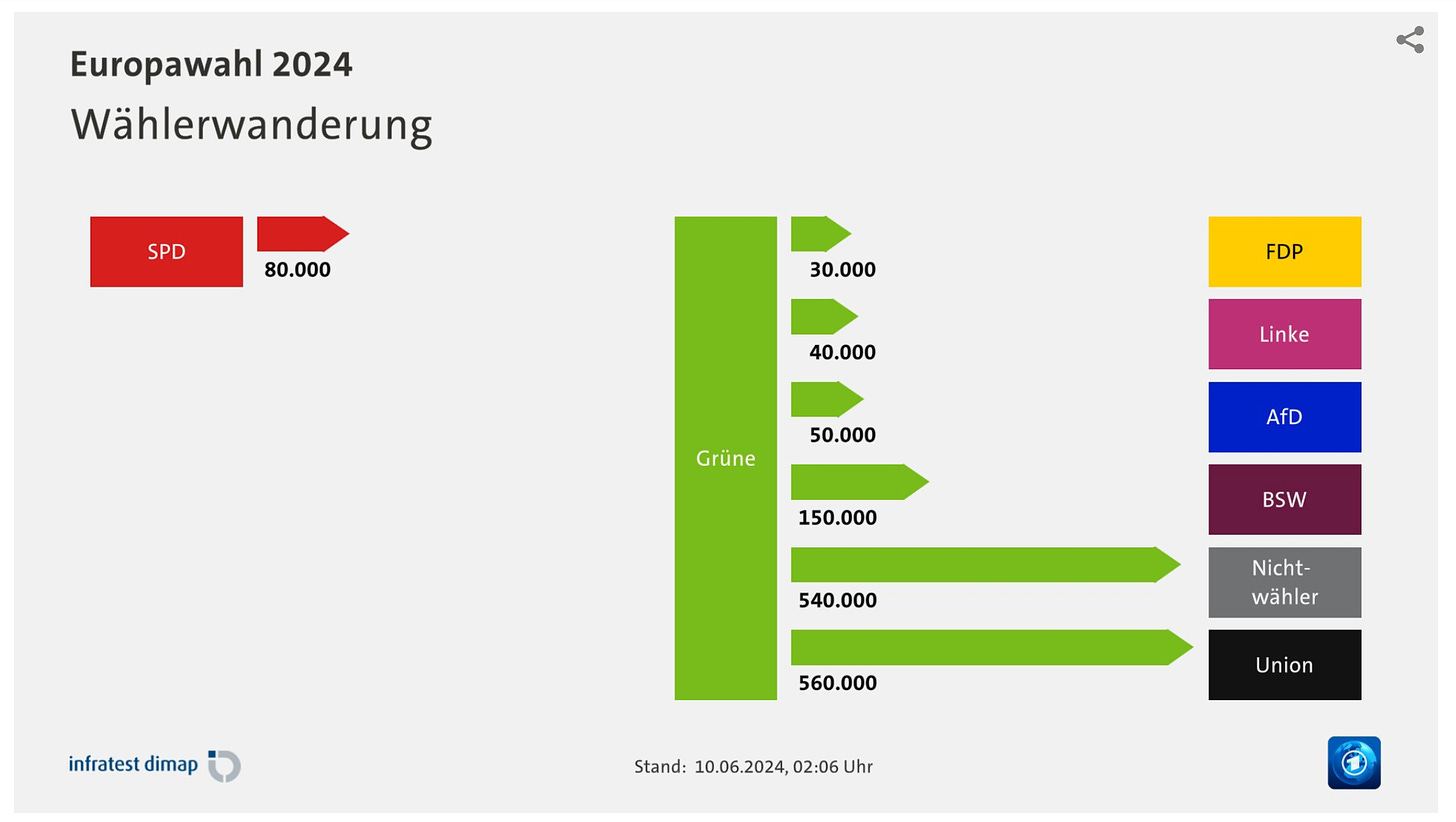

Relative to 2021, when, to their disappointment, they scored only 14.7 percent of the national vote, the Greens lost heavily to abstention and to the CDU.

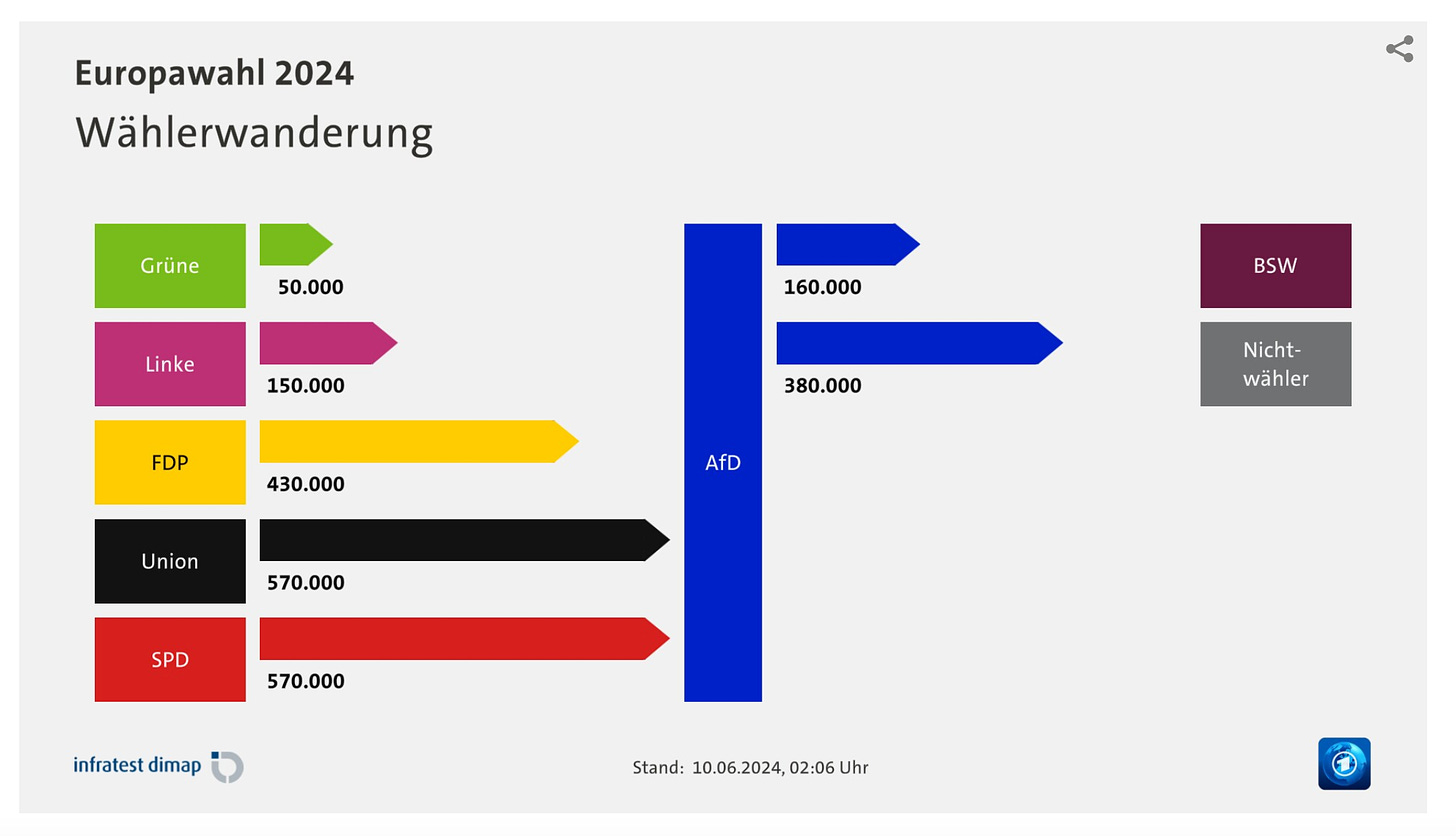

The AfD, the big winner of the election, continues to collect protest votes in equal measure from all three of the traditional parties of West Germany - the CDU, SPD and FDP. Given the underlying share of the votes, the losses for the FDP to the AfD between 2021 and 2024 are particularly striking.

To refer to the AfD vote as a protest vote is justified by the fact that when asked whether the current government should be sent a reprimand (Denkzettel), 87 percent of AfD voters agreed. 71 percent of Wagenknecht also said that they wanted to deliver a message to Berlin.

The new arrival on the scene, Sahra Wagenknecht’s party, is not the AfD killer that some imagined. She took more than twice as many votes from the mainstream right-wing CDU and FDP than from the AfD and three times as many votes from die Linke as from the AfD. Above all she attracted SPD voters.

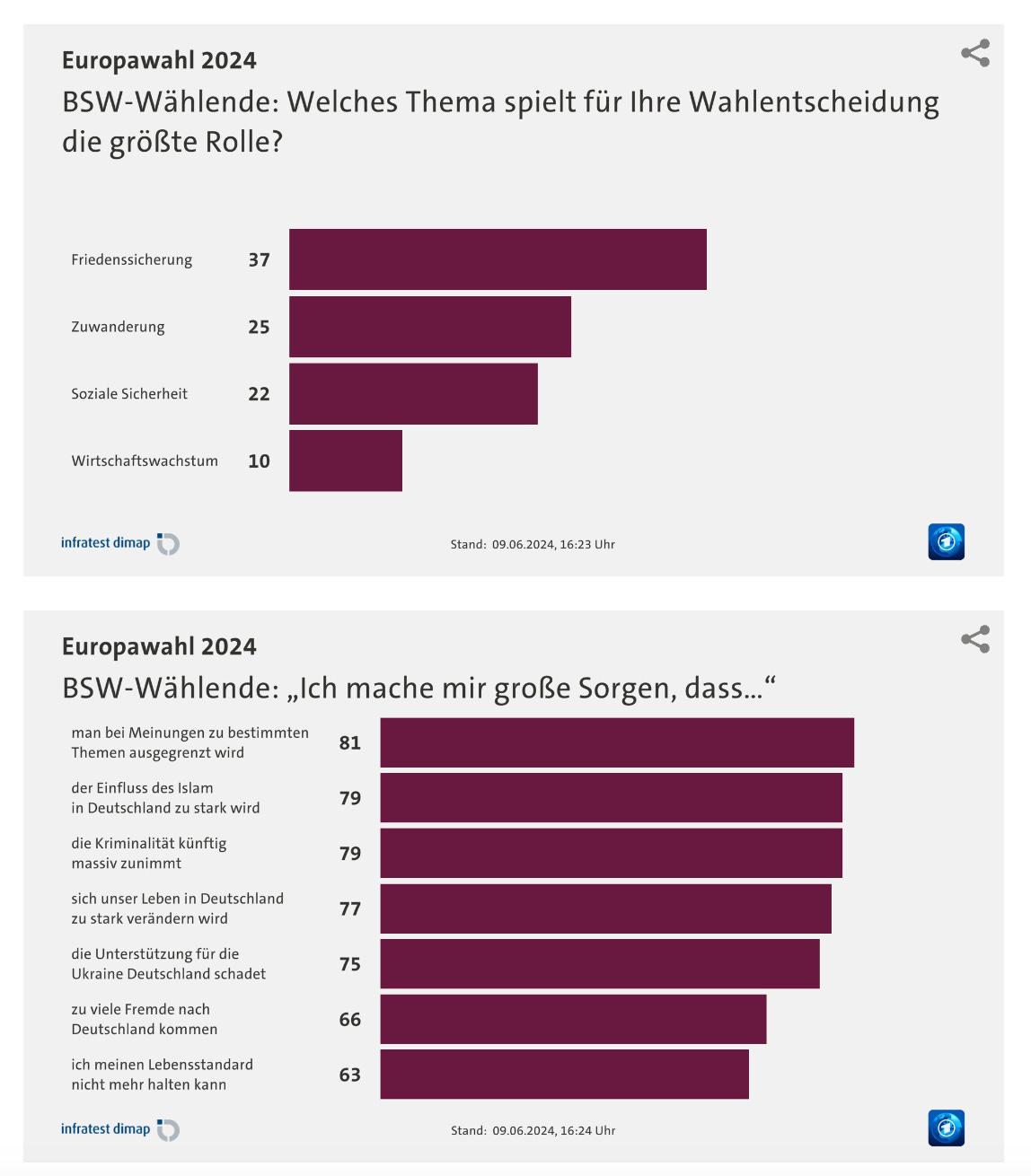

Along with delivering a protest to Berlin, Wagenknecht’s supporters are second only to the AfD in their worries about “too many foreigners”. Asked why they chose Wagenknecht the first answer was concerns about peace and the war in Ukraine. Migration came second. Asked about their worries, huge majorities of voters in Wagenknecht’s camp listed migration, Islam and criminality.

Wagenknecht, if not climate skeptical, rejects the EU’s Green Deal and favors continued gas imports by pipeline (from Russia). In TV talk show panels she likes to mock Germany’s politicians for sacrificing its advantage in the motor vehicle industry.

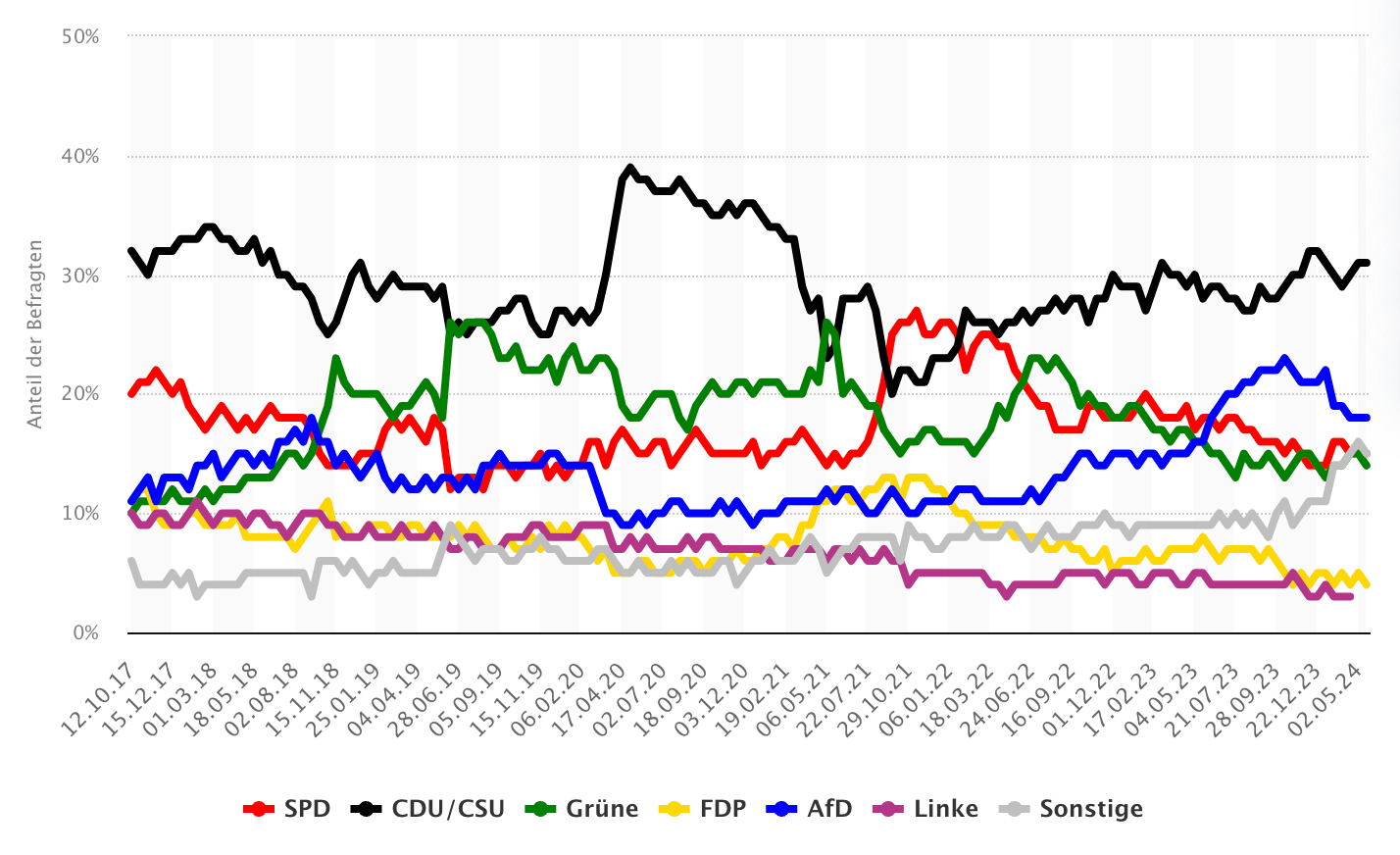

Where does this election leave Germany? To gain our bearings it is useful to consult the weekly polling conducted in the form of the “Sunday question”, the question being “How would you vote if a general election were held this Sunday?”.

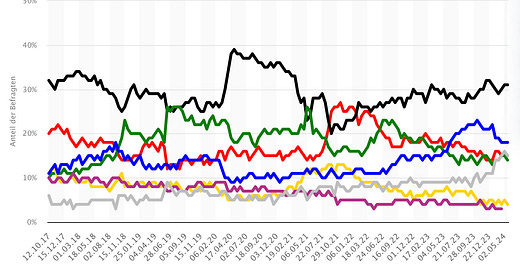

What this context reveals is that the 2024 European election result is more typical of the general balance of German public opinion than either the 2019 European election or the 2021 general election that put the current government in office. Over the last seven years the CDU/CSU, when under steady leadership, is a party that commands 30 percent of the vote. In 2021, the SPD was able to capitalize on the disastrous post-Merkel transition at the top of the CDU to boost Scholz into the Chancellory. Since then, the SPD has relapsed into a range of 15-20 percent. Over the period since 2017, Green support has followed an arc. From 2017 to 2019, the Greens, who then formed the main opposition to Merkel’s coalition government, rode the wave of climate concern and excitement about the possibilities of green modernization to what promised to be a new level, of 20 percent or more. That momentum survived the early phase of the war, but was then broken by the price spike and the botched legislative efforts of 2023. Meanwhile, the different political ecology of East Germany supports the extremist AfD and a revived left vote à la Wagenknecht.

With German elections due in 2025, the chances of another green-inspired progressive coalition look slim indeed. If the CDU sticks with its current leader Friedrich Merz, whose persona resembles that of an ill-tempered school master and is considered by German voters to be an even less suitable for the Chancellorship than Olaf Scholz, it is possible that the SPD might secure a surprise bump. Can the Greens claw their way back to the 15 percent they scored in 2021? Surely they can. But even if they do, the FDP is a lost cause and Wagenknecht is polling at 6 percent nationally. So anything resembling the constellation of 2021 is far out of reach. So long as the CDU commands around 30 percent of the vote, coalition formation will revolve around them and the business lobbies they still represent. One key question will be the CDU’s willingness to revise the debt brake that limits the scope for much needed public investment and spending on both climate and defense. A lot will depend on the balance of more or less modernizing and green-minded forces within the CDU. It is a thin thread to hang one’s hopes on.

Minor correction on the explanation of the coloring of the German election result map. The black-blue shadowing of Bavaria is not at all related to the AfD closing in second. Instead, it's the color always used for CSU election results.

Outstanding overview. Thank you.