Look around the world and ask yourself the following questions:

Q: The war in Ukraine hangs in the balance. Who ought to be most concerned? Europe. If Putin wins, whose strategic model will be most disrupted?

A: Germany.

Q: The American election hangs in the balance. Who ought to be most concerned? Europe (see above). And if Trump wins, who, in Europe, will be most disconcerted?

A: Germany.

Q: The future of the green energy transition is in the balance. Whose industrial base is most in the crosshairs of Chinese competition? Europe. If Chinese EV sweep the board, who, in Europe, will be the biggest loser?

A: Germany.

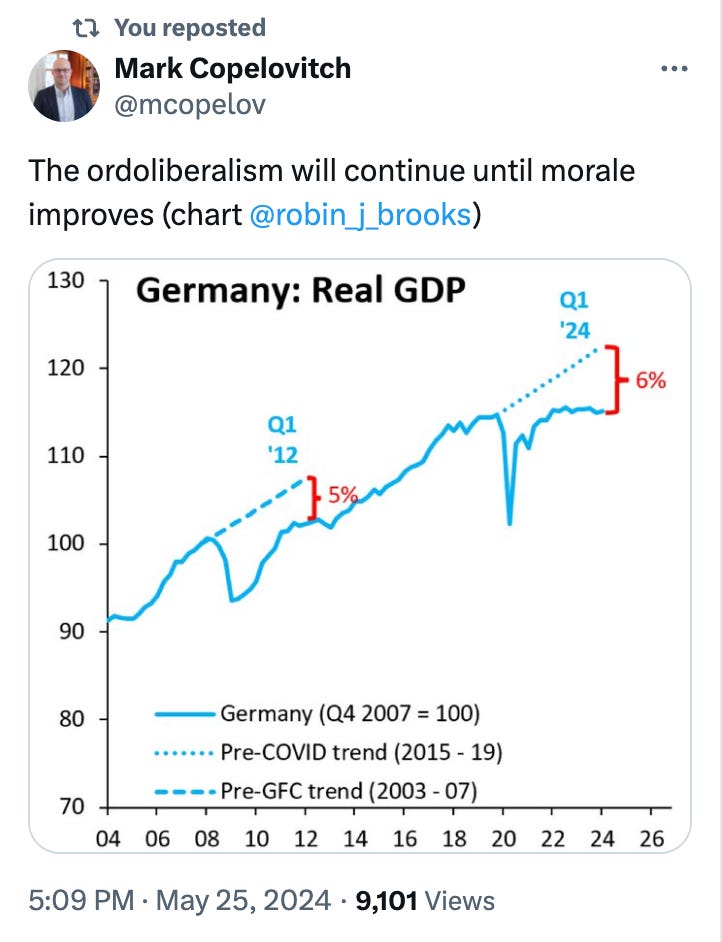

Q: The European economy look as though it may be sliding towards stagnation and lags far behind in key areas of innovation. Who has suffered particularly grievously from the triple shock of COVID, Putin’s war and the gear shift in Chinese growth?

A: Germany.

Q: The European elections hang in the balance. If on June 9th the right-wing are declared the winners, all of liberal Europe will be embarrassed. But, where will that embarrassment be most painful?

A: Germany. (Not even Europe’s other right-wing parties want to be associated with the AfD, whose lead candidate likes to make excuses for Hitler’s SS.)

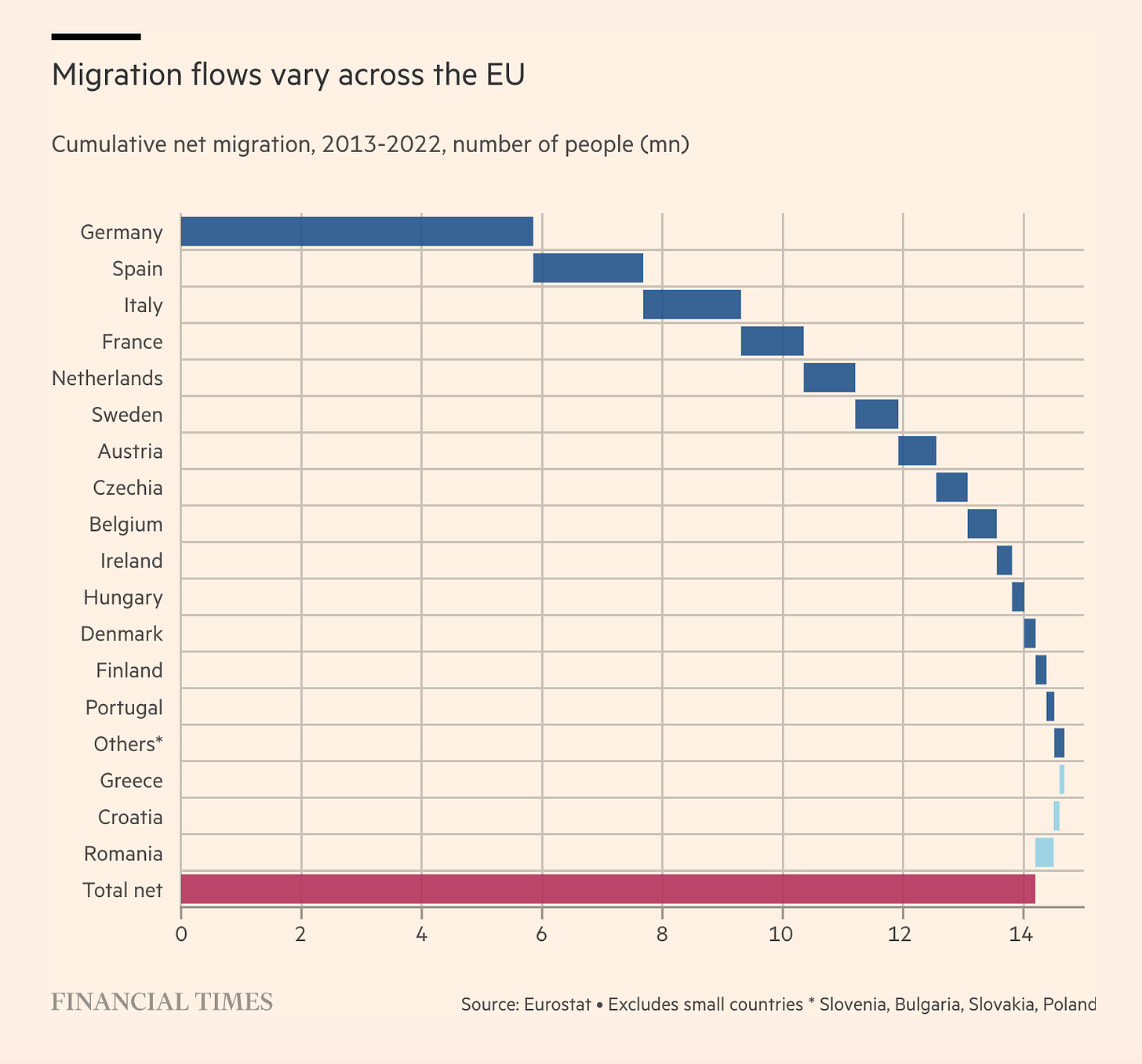

Q: Europe’s demography hangs in the balance. Migration is the central issue driving the far-right. It poses deep questions about how Europe can make work a multi-cultural, multi-faith democracy that acknowledges both its own deep, layered and traumatic history and its deep connections to the Middle East and the Muslim world - which come with its own weight of historical baggage. Where is that history most dense and most fraught, where have the recent transformations due to migration been most dramatic?

A: Yeah. You guessed it! Germany.

Source: FT

You get the picture. This would be an easy pub quiz to win at!

Clearly, Europe in general, and Germany in particular, face huge challenges. Urgent challenges. Challenges which, in the worst case, could culminate, by the end of this year, in a new phase of Europe-centric polycrisis.

Given all the talk about the EU emerging as a more realistic, sovereign, geopolitical actor, you would expect a strategic response. And from corners of Europe’s ramified political system we are getting that response.

There is the Letta report on completing the single market.

There is Mario Draghi’s widely trailed report on competitiveness, which will apparently call for “radical change”.

There are, as has frequently been the case in recent years, sensible proposals from the Spanish government for joint European borrowing to fund investment.

There are conversations sparked by the European Council about a jointly funded defense initiative. There are rumors that von der Leyen is coming around to more common debt. Mario Draghi, the dark horse for the Commission Presidency should von der Leyen failsto form a majority, is an open advocate of fiscal union.

As one would expect there are a variety of initiatives from President Macron, notably on defense but also on common European investment, culminating in a second speech at the Sorbonne.

But where is Berlin? The answer to all those ominous question is one word: Germany. If Europe needs to act, no one needs it more than Germany. But where is the answer from Berlin to the mounting chorus of opinion calling for Europe to anticipate future stress with bold action?

That is the question I ask in my latest FT column.

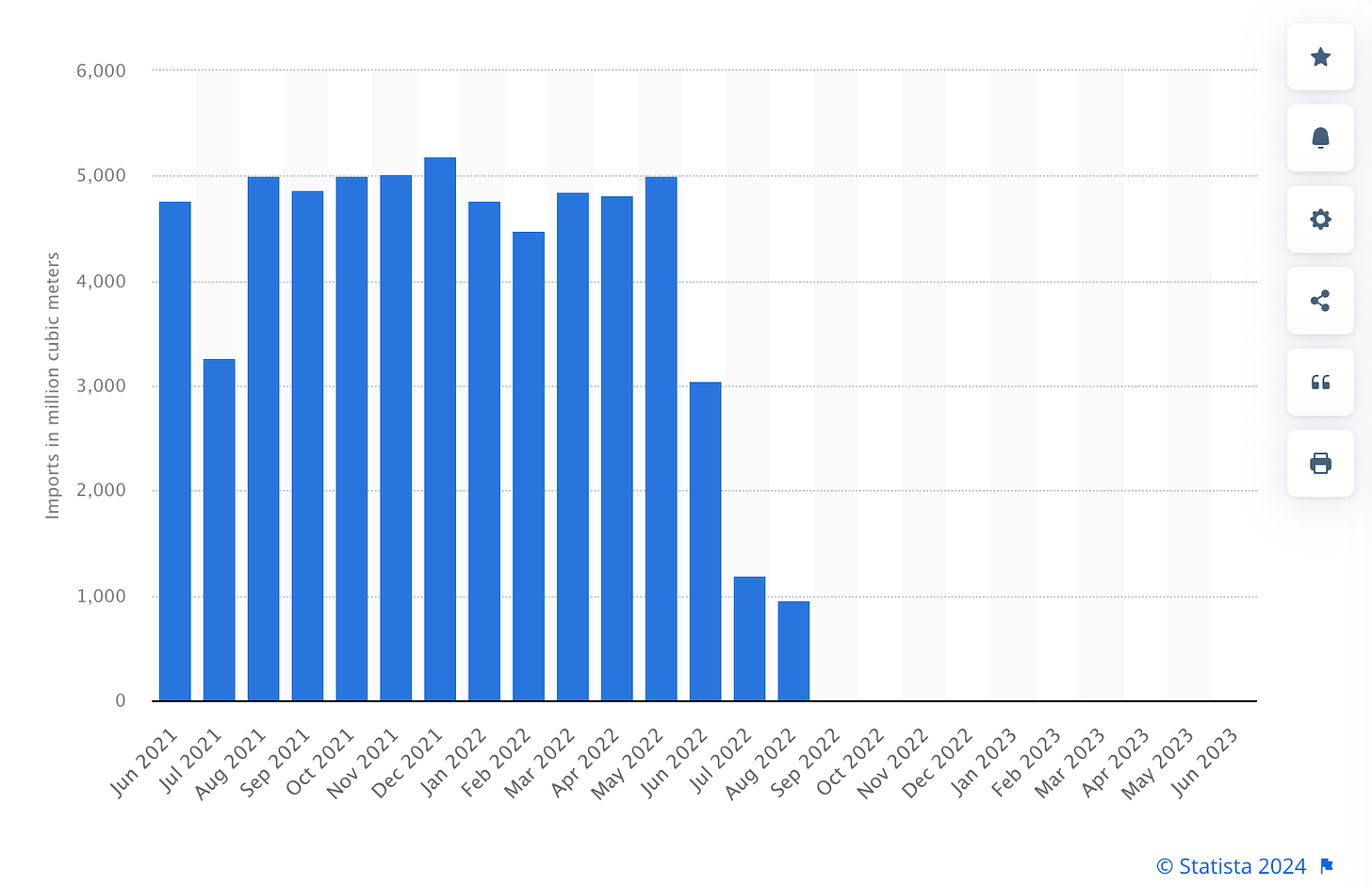

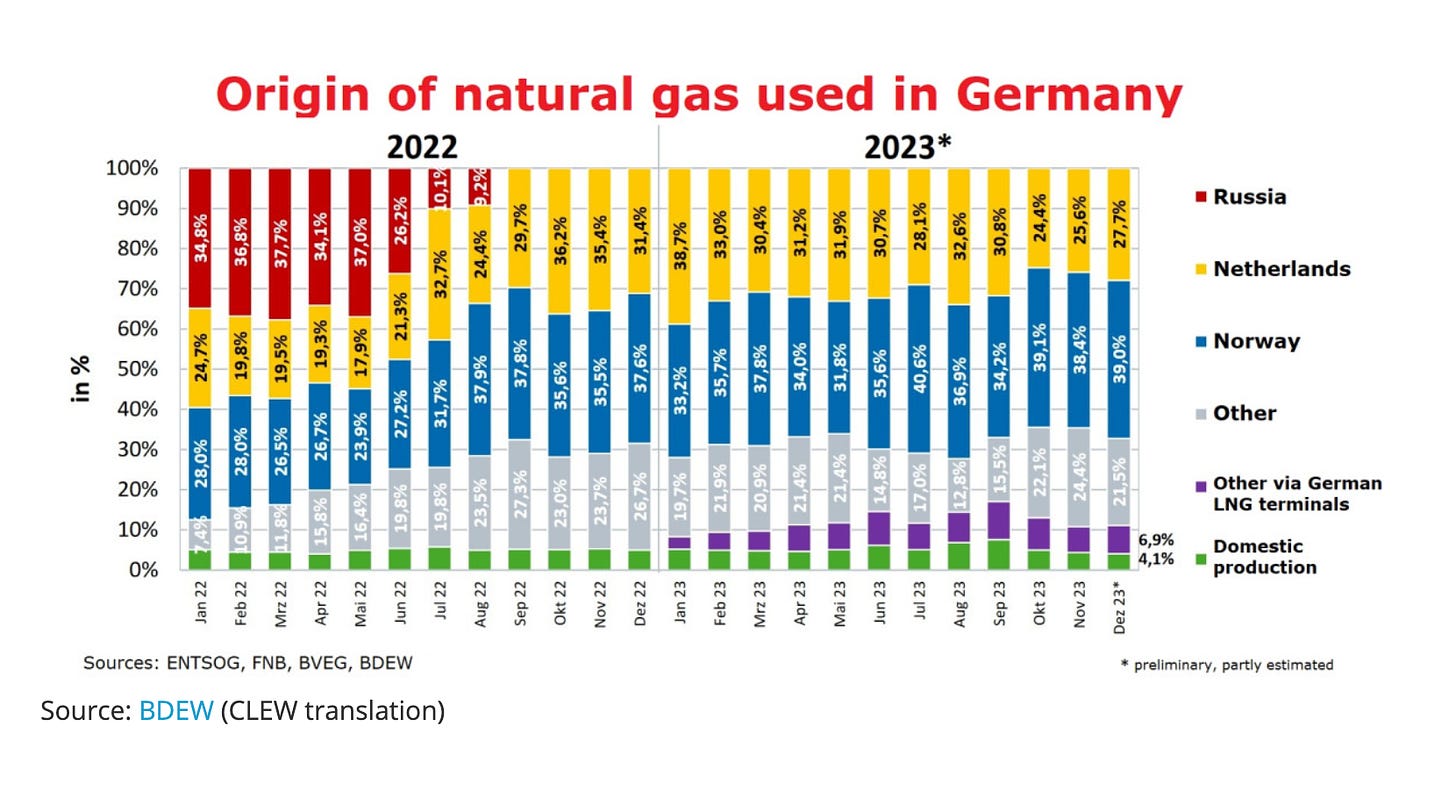

In fairness to the Scholz administration, it has had a rough ride since 2021. Priority number 1 was, of course, to survive the shock of the end of Russian gas deliveries.

Import volume of natural gas from Russia in Germany from June 2021 to June 2023(in million cubic meters)

Source: Statista

The Russian gas was made up for by purchases from world markets. This required a lot of scrambling, but one thing that Germany has, is purchasing power.

Source: Clean Energy Wire

Germany even managed to build a cluster of LNG terminals in record time - which Chancellor Scholz celebrated as “Deutschland Tempo”. They now account for just short of 7 percent of German gas imports.

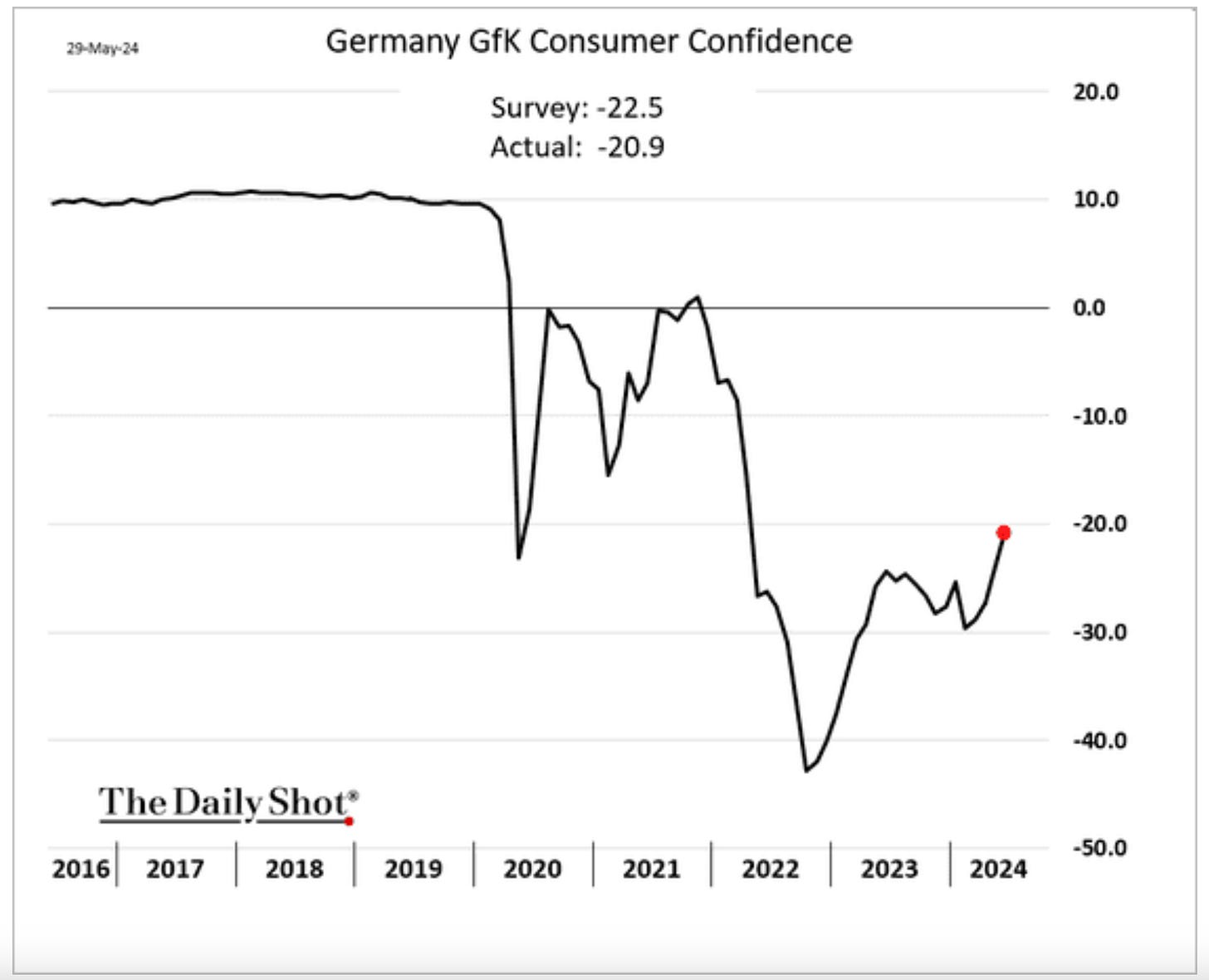

In 2020 the German general public suffered a dramatic blow to their previously deeply entrenched complacency, a blow from which they still have not recovered.

But modern history offers not let up.

Olaf Scholz’s administration clearly has a general sense of the scale of the polycrisis conjuncture. The Chancellor even invoked the term in a recent speech in Berlin. But the context he was discussing it in was global. On the world stage it is easy for Berlin to conduct itself as a cooperative player, hosting “Global Solution Summits”. But closer to home, in Europe, where Germany is not just helpful and cooperative but a decisive force, what is the Scholz agenda?

Here is the uncut version of my FT column.

“Our Europe is mortal. It can die.” So said President Emanuel Macron of France in a recent speech to the Sorbonne. Given the trouble on Europe’s horizon, you can see his point.

The war in Ukraine has swung to Russia. Europe’s economy limps behind the US. The immigration question looms on the southern border. The far right is surging. To avoid falling off a cliff in 2026, Europe’s much hailed Green Deal needs refunding.

If Trump wins in November, he will pull the United States out of the Paris climate accords and put the future of NATO in question.

Of course, recognizing your mortality is not the same as facing an immediate death sentence. But, by the end of 2024, it is easy to conjure truly dark scenarios. In light of this, you might expect that Europe’s capitals, led by Paris and Berlin, would be scrambling for a grand bargain on common defense, investment and green spending.

Instead, what emerged from three days of Franco-German summitry this week was a limp joint statement. Anyone looking for inspiration will be disappointed. The two leaders evoked sovereignty but delivered none of its substance. Their main buzzwords -competitiveness and capital markets union – are well-worn boilerplate of EU communiques. The emphasis on competitiveness is a reflex of the daunting geoeconomic environment. Promising capital markets union sidesteps the question of common European borrowing.

Paris is not to blame for this impasse. As he struggles to avoid the label of lame duck, Macron has been spurred, once again, into bold thinking. He has called for a doubling of the EU budget and a big investment push. He has a strong ally in Spain. In the Council there have been calls for defense spending to be funded by common borrrowing.

Despite the risks on the horizon, none of this finds any echo in Berlin. Nothing new there. Berlin has long been a drag on Macron’s European ambition. But, Germany is finding new ways to disappoint.

In the past, Germany dragged its feet in Europe because it felt strong and thought that time was on its side. This was always wrong-headed. Germany too paid a price for the disastrous mishandling of the eurozone crisis. Today, complacency is even more out of place.

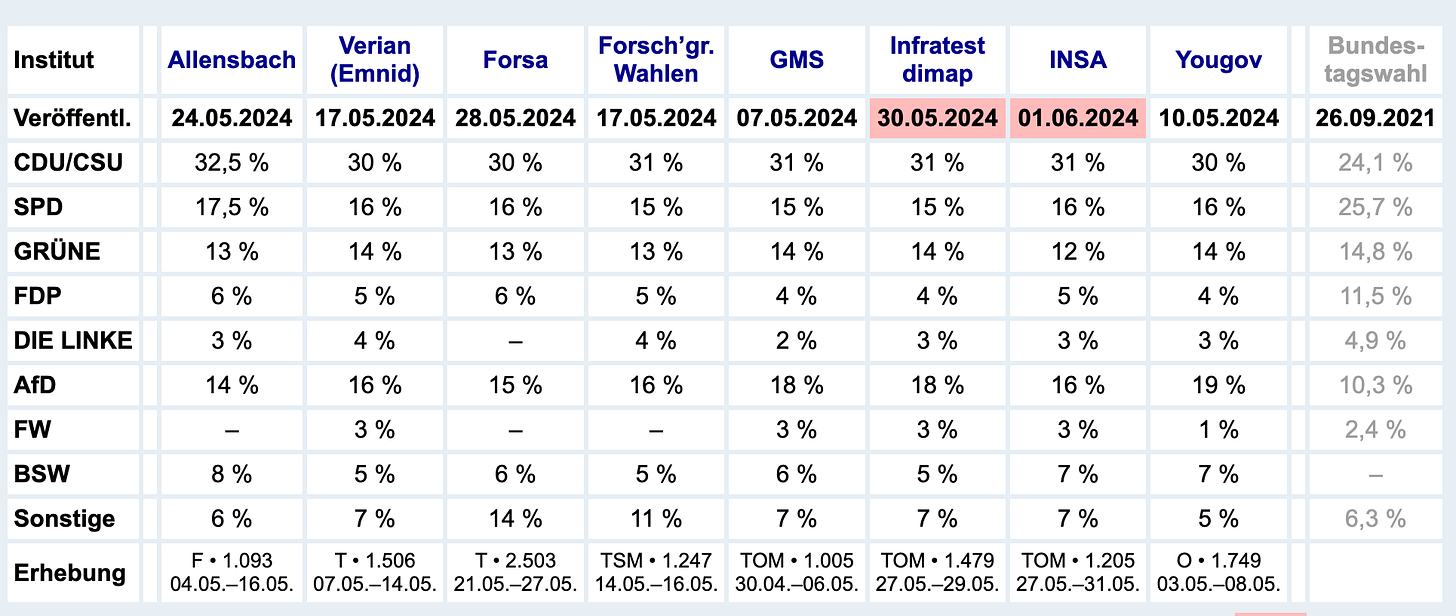

Unlike France, Germany is militarily defenseless and painfully dependent on the USA. If Trump is elected for a second term, no one will receive a less warm welcome in Washington than Olaf Scholz. Germany’s energy policy is in disarray. Germany’s fabled manufacturing sector faces an uncertain future. The right-wing AfD, which has surged in the polls, is so disagreeable that Europe’s other rightist want nothing to do with them.

If Germany’s government is stalling in the face of all this, it is not a sign of complacency, but of paralysis.

Back in August 2022, as Ukraine was poised to launch its dashing counteroffensive, Chancellor Scholz in his Prague speech, laid out a bold vision of European eastward expansion. Fast forward to 2024, as Ukraine struggles to hold the line, that prospect is receding into the distance. At home, the reform promise of Scholz’s government has not aged well. What secured the SPD’s surprising victory in 2021 was the promise of a “normal life” for their aging electorate. Given Germany’s standard of living that is a soothing prospect. But as has become clear, for things to stay the same much must change, and this is where Scholz falls down. At first, he left it to the Greens to dynamize his coalition. But a savage backlash on the energy transition and agriculture has turned the environmentalists into scapegoats of the nation. And the hostile fire has come not just from the tabloid Bild Zeitung, but from within the coalition from the “Autobahn liberals” of the FDP.

Allowing Christian Lindner to claim the finance ministry was a high-risk gamble. At first he showed flexibility, but increasingly he has dug in his heels on debt. On Europe the Minister and his team openly polemicize against any further common debt issuance.

This stonewalling might be understandable if it brought in the votes. But support for the FDP has crashed. In a general election, Germany’s Finance Minister, would likely be outscored by the one-woman party of left-wing maverick Sarah Wagenknecht.

Source: Wahlrecht.de

Lindner’s latest stunt is to pick a fight with the only truly popular politician in the government, Defense Minister Boris Pistorius. Lindner’s demand is that Pistorious should cut 6 billion Euros from Germany’s defense planning (Pistorius is trying to raise the budget). With Berlin in this state, it is little wonder that Europe is drifting.

Optimists will insist that if it comes to the worst, Europe will once again find a way through. They may be right. But crisis-fighting at the EU-level – whether in 2012 or 2020 – depends on choices made in Berlin. On both occasions, Angela Merkel overrode the right-wing of her own party. Would Scholz risk political survival to strongarm his Finance Minister for the sake of Europe? It is far from certain. And if it comes to an election, what is the alternative? Friedrich Merz who, as head of the Christian Democrats is leading in the polls, prefers the role of the divisive polemicist to that of constructive opposition.

When, amidst the Eurozone crisis, Berlin was dubbed Europe’s reluctant hegemon that implied strategic choice. Today, faced with even greater perils, what prevails in Berlin is not deliberate restraint, so much as a vacuum of European policy.

In response to the op-ed my friend Shahin Vallée, who is as insightful and deeply informed on EU affairs as they come (check out his Substack Geoeconomics), remarked that he liked my critique of Berlin, but he thought I was too kind to Paris.

Clearly, Macron is a man fighting for his political legacy. His ratings are terrible. His party is likely to suffer humiliation in the European elections. France’s debt was downgraded by S&P and Macron is at odds with his powerful finance minister Bruno Le Maire. So how does Macron react? With a big speech. This is now a stereotype and it is no secret that it irritates Berlin.

But, be that as it may. France remains the number 2 economy in Europe. It is clearly an indispensable partner and one you don’t want to act without. The threats facing Europe are serious. Germany needs a way around the national impasse created by its constitutionally anchored debt brake. And if Macron is lame duck, Scholz is hardly in great shape either. He governs, one is tempted to say, as the Chancellor of a minority government.

In the expanded, complex and more multipolar Europe, the Franco-German engine of old, is not what it once was. As one Politico piece commented:

Move over, Paris and Berlin. A new cast of European leaders is looking to step up as power brokers on the European stage, and your time in the driving seat may be coming to an end.

But all of this makes it more necessary for Berlin to grit its teeth and get down to business with Paris. Their joint action was the core of Europe’s last great lurch forward, the NextGen EU program in the summer of 2020. If Macron’s appeals for grand bargains are over-dramatic then substitute your own more adequate version of an answer. Clearly, Macron’s French government is the weaker party here. So in their joint interest, Berlin should bend towards Paris. Instead, what we see from Berlin are provocations, over military deliveries to Ukraine, common defense projects (air and missile defense) and France’s commitment to nuclear power.

It is the inability of Germany’s coalition government to concert itself so as to be able to engage with France and to make the best of what weight they still command that is the worrying aspect of the current moment. The politics of the three-way coalition in Berlin may seem trivial. They often are. But, as is true elsewhere, they reflect deep divisions within Germany’s seemingly peaceful and reconciled society - a topic to which we will return. If the going gets rough for Europe in the coming months those divisions and the ability or inability of the Scholz coalition to bridge them, may become decisive for the EU as a whole. As is often the case, the prospects for a “grand bargain” my hang on politics that are far from grand.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to over one hundred thousand readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Your question has an easy answer. You are assuming that Germany is a subject. Yet nord stream has clearly shown it is an object. You can pretend otherwise only if you exclude the fact of nordstream from the model. But then it’s a critically incomplete model that will produce wrong results no matter what you ask.

And no, it’s not Ukrainians who did it, if you come back with that.

"Q: The war in Ukraine hangs in the balance. Who ought to be most concerned? Europe. If Putin wins, whose strategic model will be most disrupted?"

It has not been "in the balance" for almost 2 years. It has been pretty much one way slaughter all the time, even on the ocasions Russia chose to retreat. US is close to having fought this to the very last Ukrainian. Maybe 100k left, they started with 700k, called up over a million. Half a million is best guess of dead, half a million seriously wounded, half a million runaway. Maybe 50-70k Russian dead but 800k called up reservists or volunteers all with 3-6m minimum training.

This is denialism on a larger scale than Afghanistan.