Chartbook 284 The beginning of a new era: How the "global" energy transition is happening in China (Carbon Notes 13)

In May 2024 the clean energy think tank Ember published a worldwide Review of electricity generation that announced a profoundly important historical turning point.

Electrification is key to the new energy system that is being built around the world. Electricity generation is one process we do know how to decarbonize. With concerted action, net neutrality is within reach in electric power generation for OECD countries by the 2030s and for the whole world by 2045. Furthermore, as Ember points out, electrification will replace “fossil fuel burning that currently takes place in car and bus engines, boilers, furnaces and other applications”.

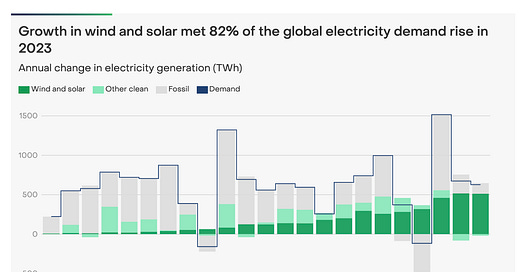

Green electrification is the key to the future. And in 2023, according to Ember’s report, almost the entirety of new power demand was covered by growth in renewables, above all solar. Though there was growth in demand for electricity around the world, fossil fuel generation barely increased. Growth in solar and wind alone were sufficient to cover 82 percent of new electricity demand.

This is not new in rich countries. In the OECD demand growth for electricity is not strong or is even negative and renewable investment has been ongoing for two decades. The sensation is that this is now happening at the global level where the growth in demand for electric power is relentless.

In 2024 Ember expects the trend to be even more pronounced. This year, for the first time there will be substantial growth in global demand for electricity, whilst fossil fuel generation will likely fall.

Demand growth in 2024 is expected to be higher than in 2023 (+968 TWh) but clean generation growth is forecast to be even greater (+1300 TWh), leading to a 2% fall in global fossil generation (-333 TWh).

The tipping point would already have arrived in 2023, according to Ember, if hydro power generation had not been badly affected by drought. The short fall in clean power capacity due to low water levels in reservoirs led several countries to resort to more coal-fired power generation.

The coverage of the Ember report is a triumph of data collection. It is remarkably comprehensive and up to date and covers generation rather than capacity installed.

Ember’s fifth annual Global Electricity Review provides the first comprehensive overview of changes in global electricity generation in 2023, based on reported data. It presents the trends underlying them, and the likely implications for energy sources and power sector emissions in the near future. With the report, Ember is also releasing the first comprehensive, free dataset of global electricity generation in 2023. The report analyses electricity data from 215 countries, including the latest 2023 data for 80 countries representing 92% of global electricity demand. The analysis also includes data for 13 geographic and economic groupings, such as Africa, Asia, the EU and the G7

This heroic collaging of data streams allows us to map the uneven and combined development of the energy transition around the world. As Ember reports

Already the rollout of clean generation, led by solar and wind, has helped to slow the growth in fossil fuels by almost two-thirds in the last ten years. As a result, half the world’s economies are already at least five years past a peak in electricity generation from fossil fuels. OECD countries are at the forefront of this, with power sector emissions collectively peaking in 2007 and falling 28% since then.

But the real action in the Ember report is not in OECD countries. There is an obfuscation involved in talking about “the global” when, in fact, there is one country that dominates the entire dynamic of the energy transition: China.

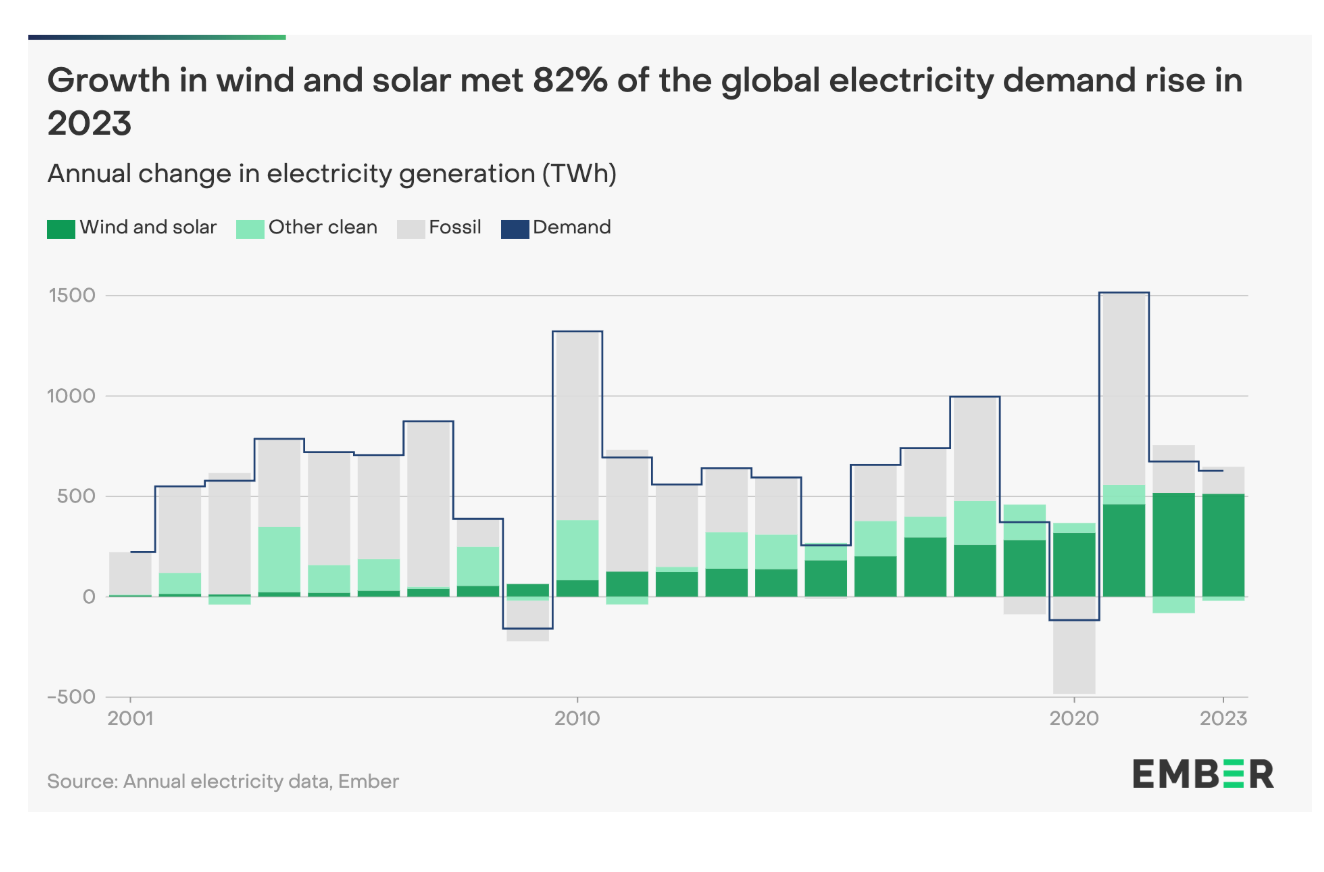

As Ember’s data show: “China remained the main engine of global electricity demand growth. China’s rapid growth (+606 TWh, +6.9%) was just 21 TWh lower than the net global increase. India’s growth (+99 TWh, +5.4%) was the next largest contributor.”

Until the 2010s China fed its voracious demand for new power with coal-fired power stations. The energy transition in the advanced economies was never going to be sufficient to offset this. Of course, the renewable energy transition in the West was also painfully slow. But even if the USA and the EU had taken more drastic action, China’s growth was simply too large and too dirty. The fact that we are now reaching a turning point in the balance between fossil and clean power generation is due to a turning point in China: a huge surge in renewable energy investment.

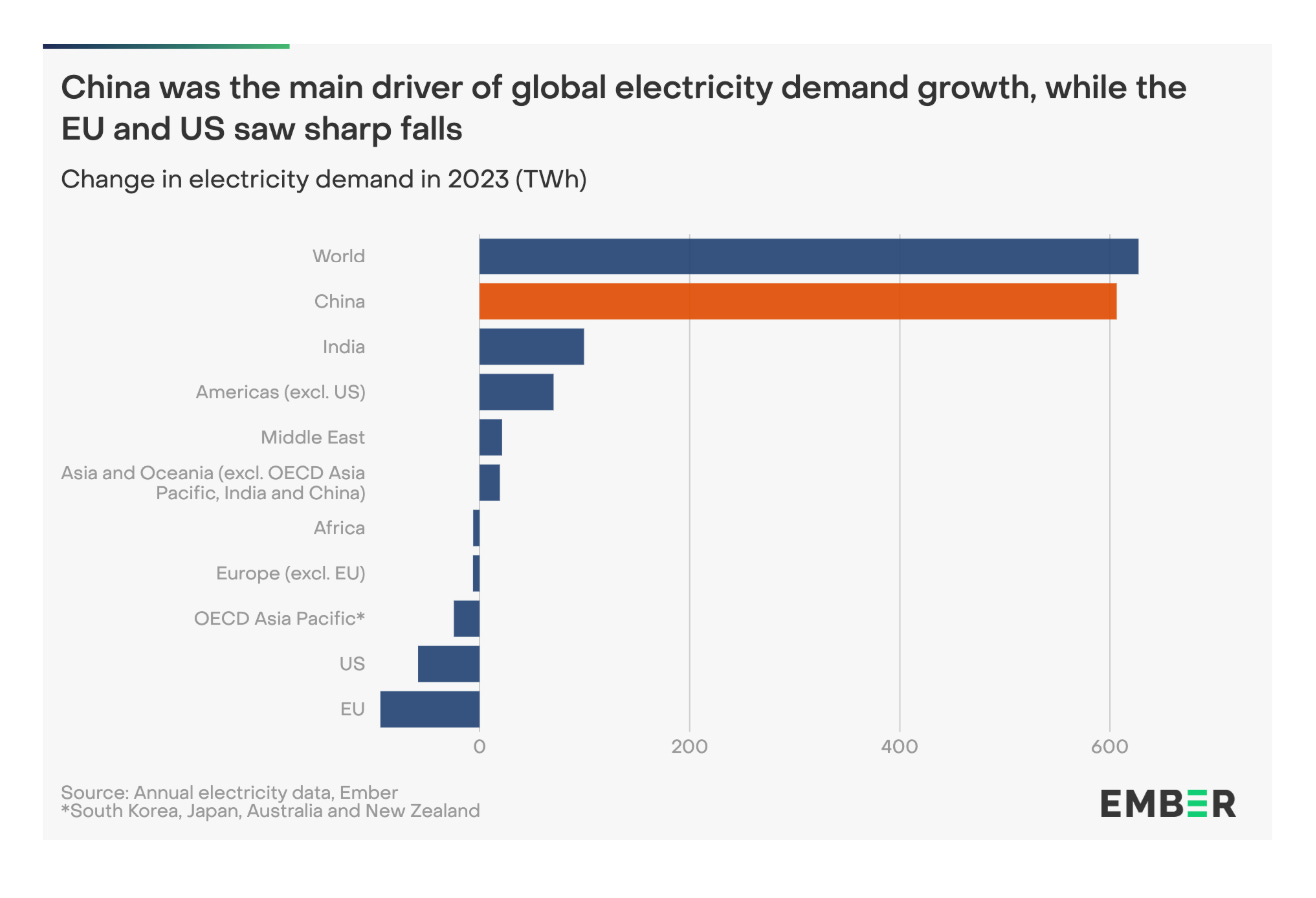

In 2023 China alone accounted for more than half of the new global additions in wind and solar.

And this is a pattern which goes back several years. As Ember reports, China’s energy dynamics dominate all the global trends.

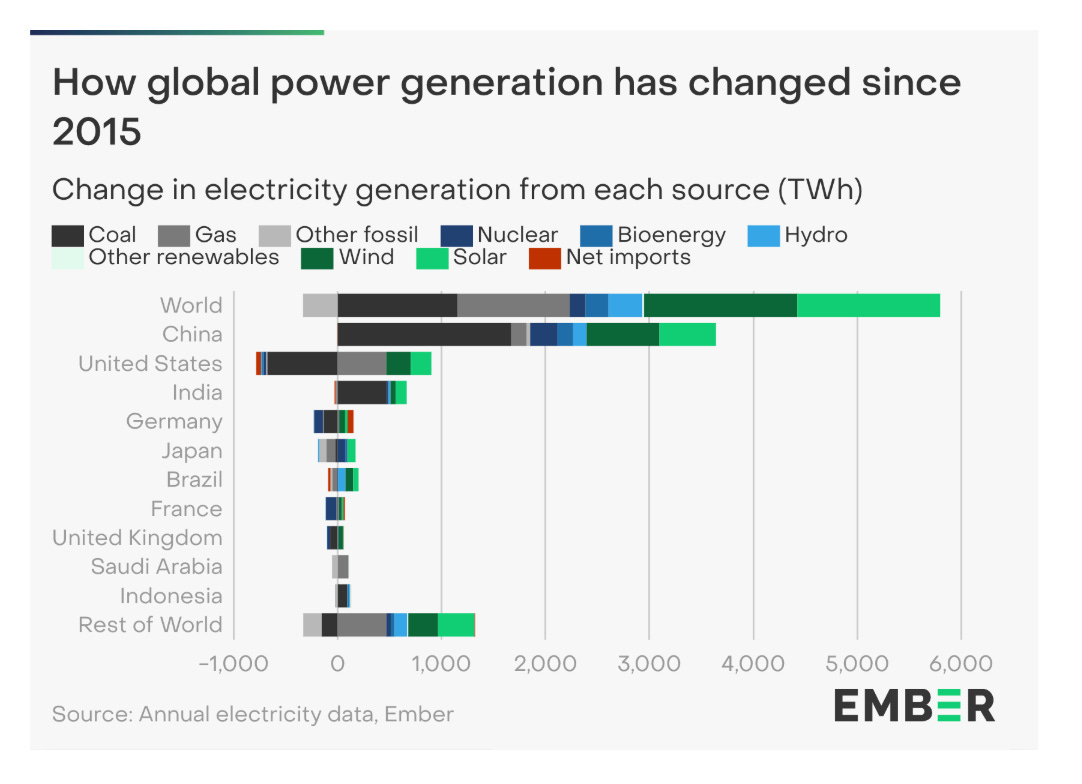

China’s growth in coal generation (+1,670 TWh) since 2015 amounted to more than the overall global increase, as coal generation fell significantly in the US and other countries in that period.

In effect, China in the three decades between 1990 and 2020 enacted a planetary scale industrial revolution in one country with such intensity that it entirely dominated global energy growth.

Now, since 2015 it has also embarked on the most gigantic green energy push, dwarfing anything seen in the rest of the world.

China also contributed nearly half (47%, 700TWh) of the global growth in wind and 40% (545 TWh) of the increase in solar generation from 2015 to 2023.

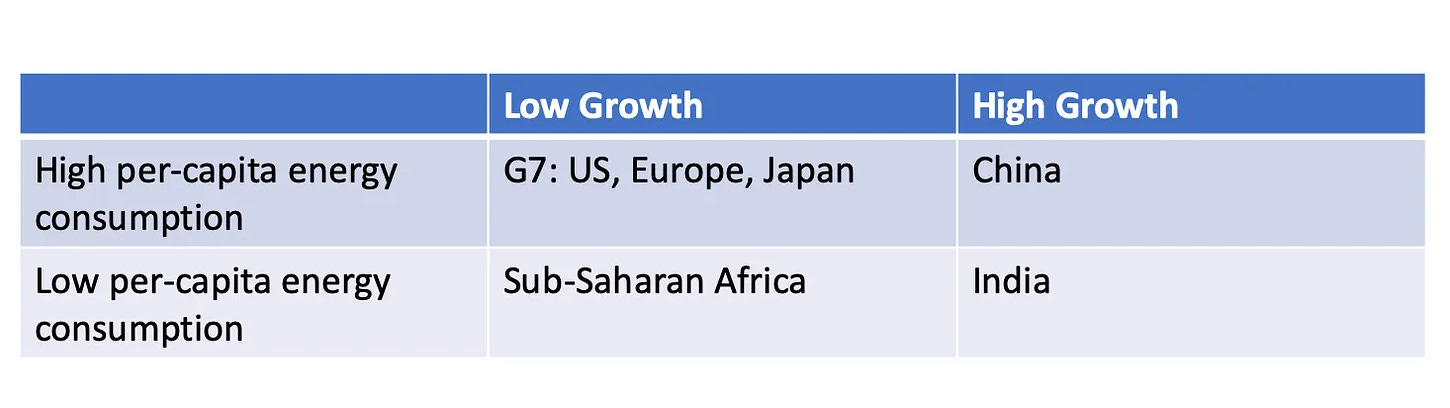

These are the numbers behind the four quadrant view of the global energy transition I’ve been pushing for a while:

The four boxes in this chart describe different energy transitions, but in quantitative terms they are very unequal. The increasing demand for power in India and EM (bottom right) is offset by the gradual fall in the advanced economies (top left). Africa’s demographic development (bottom left) is dramatic but has little or no immediate impact on the global CO2 balance. The result is, that the entire “global” drama is actually being played out in China.

And, as Ember points out, the drama of green electrification is only just beginning. It is one thing to replace dirty power generation for existing uses with solar and wind. It is another to build out the entire electricity system to meet the new demands for electricity in data-processing, transport, domestic and industrial uses.

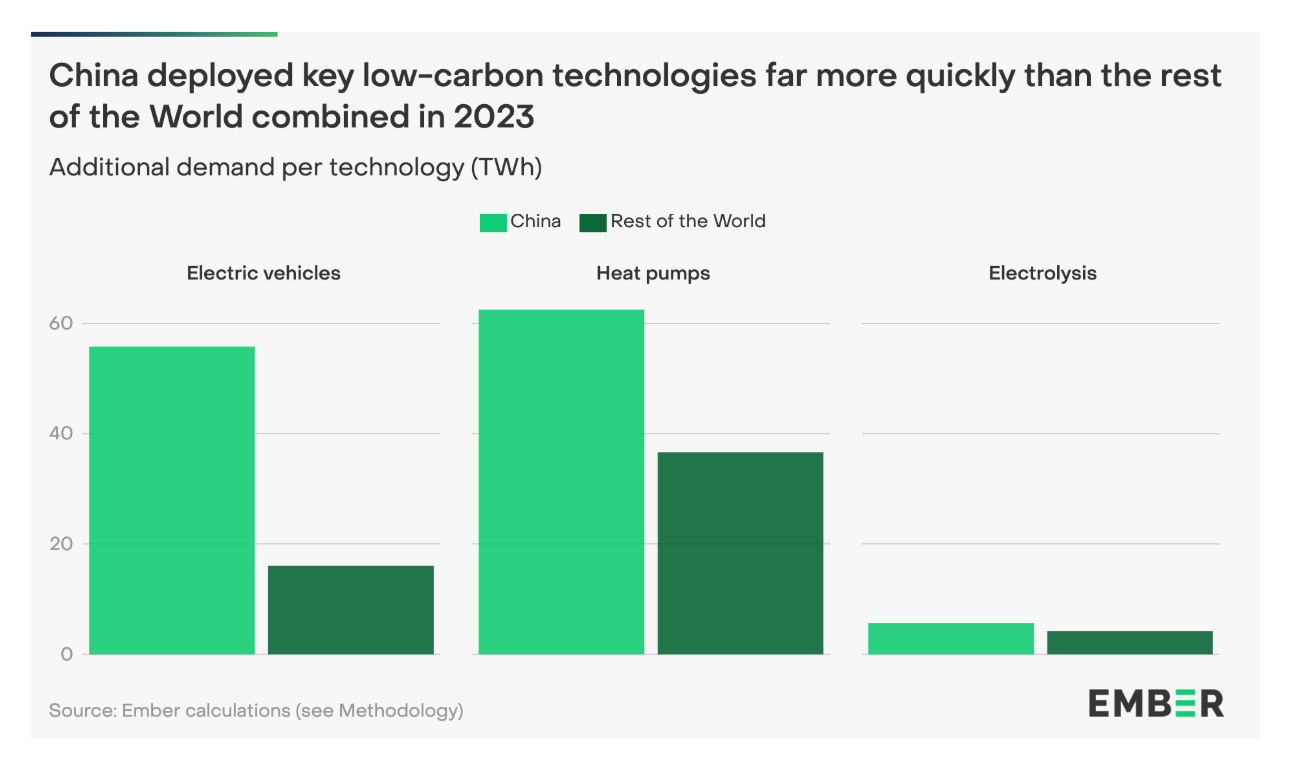

We can measure the scale of this transition, by the share of new electricity demand that is due to new types of power consumption e.g. for electric vehicles. Again, Ember’s data leave no doubt that China is far ahead of the rest of the world:

China is ahead of the curve in electrifying heating and transport and building electrolyser capacity. In 2023, China’s electricity demand from the charging and battery swapping service industry grew by 78% and added an estimated 56 TWh to China’s electricity demand – 3.5 times more than the rest of the world.

Yes you read that right. Measured in terms of power consumed China’s electrification of road transport is 3.5 times larger than that of the entire rest of the world. That is the EV revolution that the West is so worried about.

While China accounts for 60% of electric light-vehicle sales, this segment represents only an estimated 18 TWh of the 56 TWh demand increase, with the rest coming from electric vans, trucks, buses and twowheelers, which China dominates globally. It is also the largest heat pump market in the world with more installations per year than any other country. Electrolysers, used mostly in demonstration plants by chemical and petrochemical companies, have also grown faster in China than the rest of the world. As a result, China accounted for 50% of global electrolyser capacity in 2023.

But as Ember notes, this process of applying electricity to new uses, is only at the beginning.

Even in China, electrification is still in its infancy. Only a fifth of China’s electricity demand growth in 2023 (124 TWh of 606 TWh) was from the three electrification technologies, but this share will rise in time. These technologies added 1.4% to China’s electricity demand in 2023, up from 1.1% in 2022. Meanwhile in the rest of the world, electrification added 0.25% to electricity demand in 2022 and 0.28% in 2023. As China further accelerates the deployment of key electrification technologies and the world continues to catch up, the contribution of electrification will expand even further.

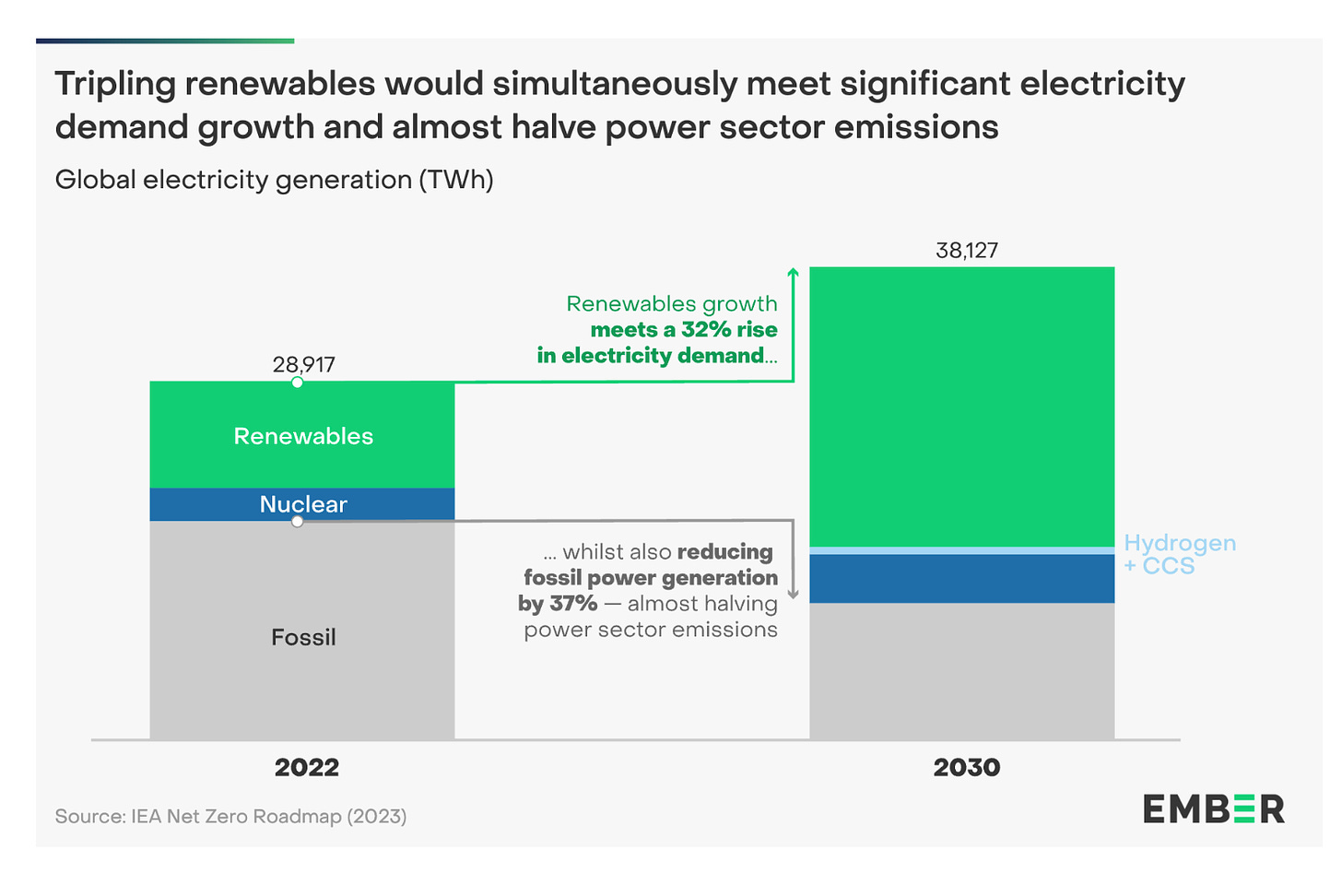

At COP28 in 2023 many countries around the world committed to tripling global renewable electricity capacity by 2030. This has the potential to almost halve power sector emissions by 2030, as coal-fired power generation will be replaced first. Furthermore, it will provide enough new electricity to replace drive forward the electrification of transport, home and industrial heating with a 32 percent increase in electricity demand.

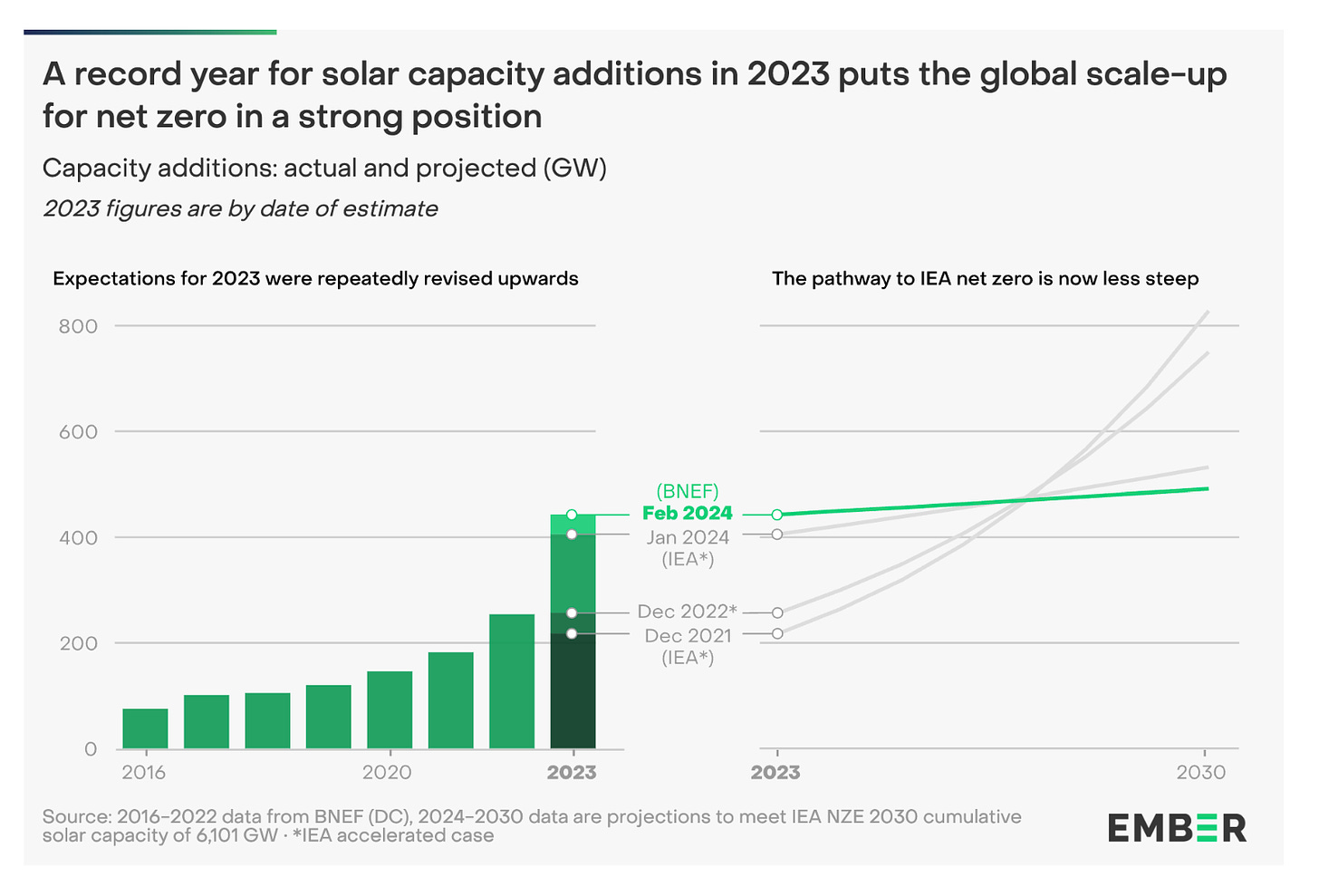

China’s huge surge in renewable energy, above all in solar power, actually puts us on track for the first time to meet these objectives. As Ember reports it has taken experts around the world by surprise:

Each year the IEA has upgraded predictions: from 2021 to 2022 to 2023 the IEA’s accelerated case scenario predicted that 2023 annual additions would be 218 GW, 257 GW, and 406 GW, respectively. With recent updates from China, the actual additions for 2023 are 444 GW according to BNEF. To put the scale of additions in 2023 into context, annual additions of solar capacity had not broken 200 GW per year until 2022, which itself was a record year.

Having shattered all previous experience of renewable power rollout, China’s huge surge in solar now actually puts us within striking distance of achieving a net zero path, driven by green electric power.

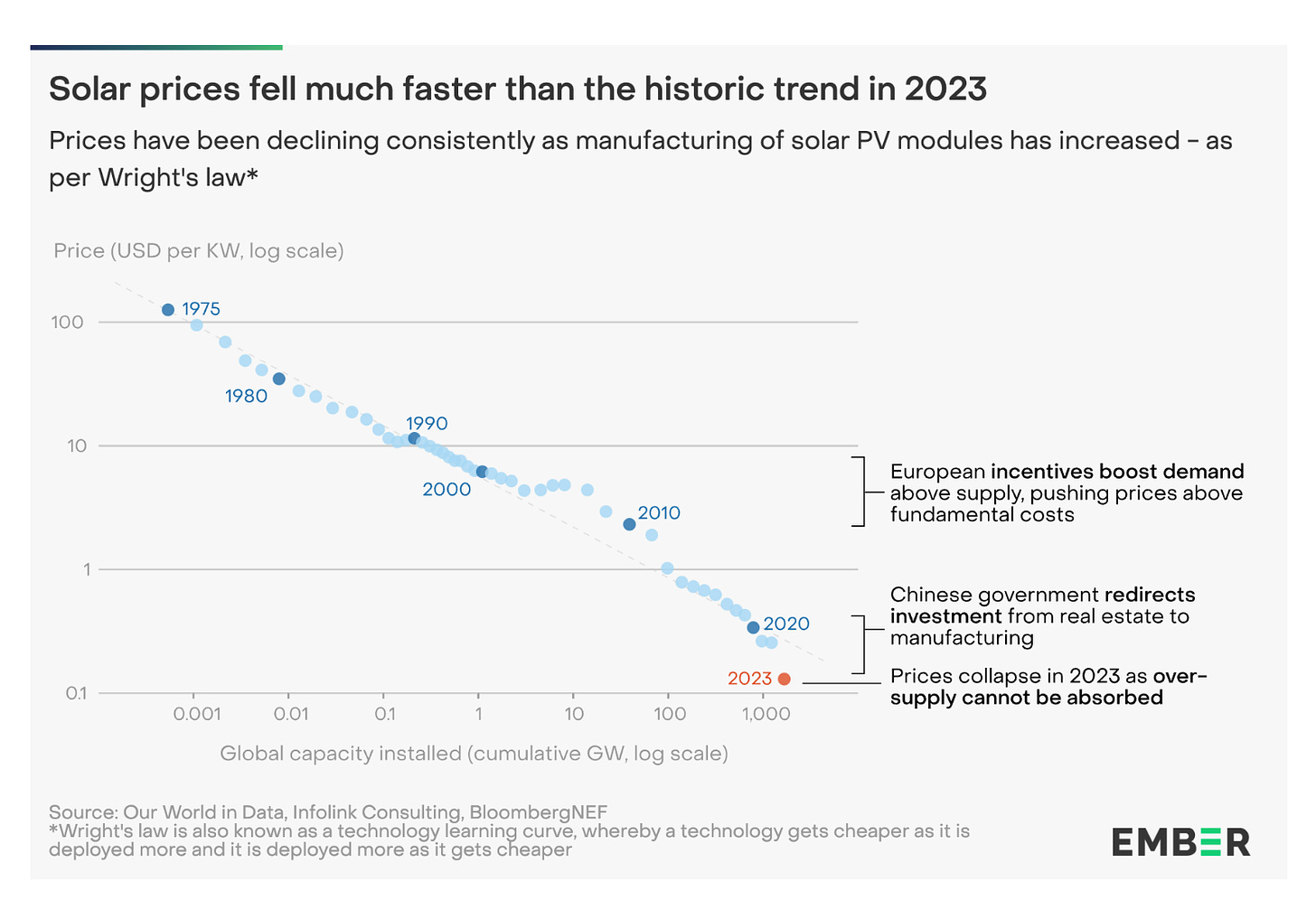

In 2023, the amount of solar manufactured in China outpaced global demand, with module spot prices collapsing by more than 50% in the second half of the year and pushing domestic installations higher and higher. Solar module prices are now significantly lower than would be expected based on Wright’s law of technology learning curves. As Chinese state lending has been increasingly redirected from the residential sector to manufacturing, the country now accounts for 80-85% of global solar module production.

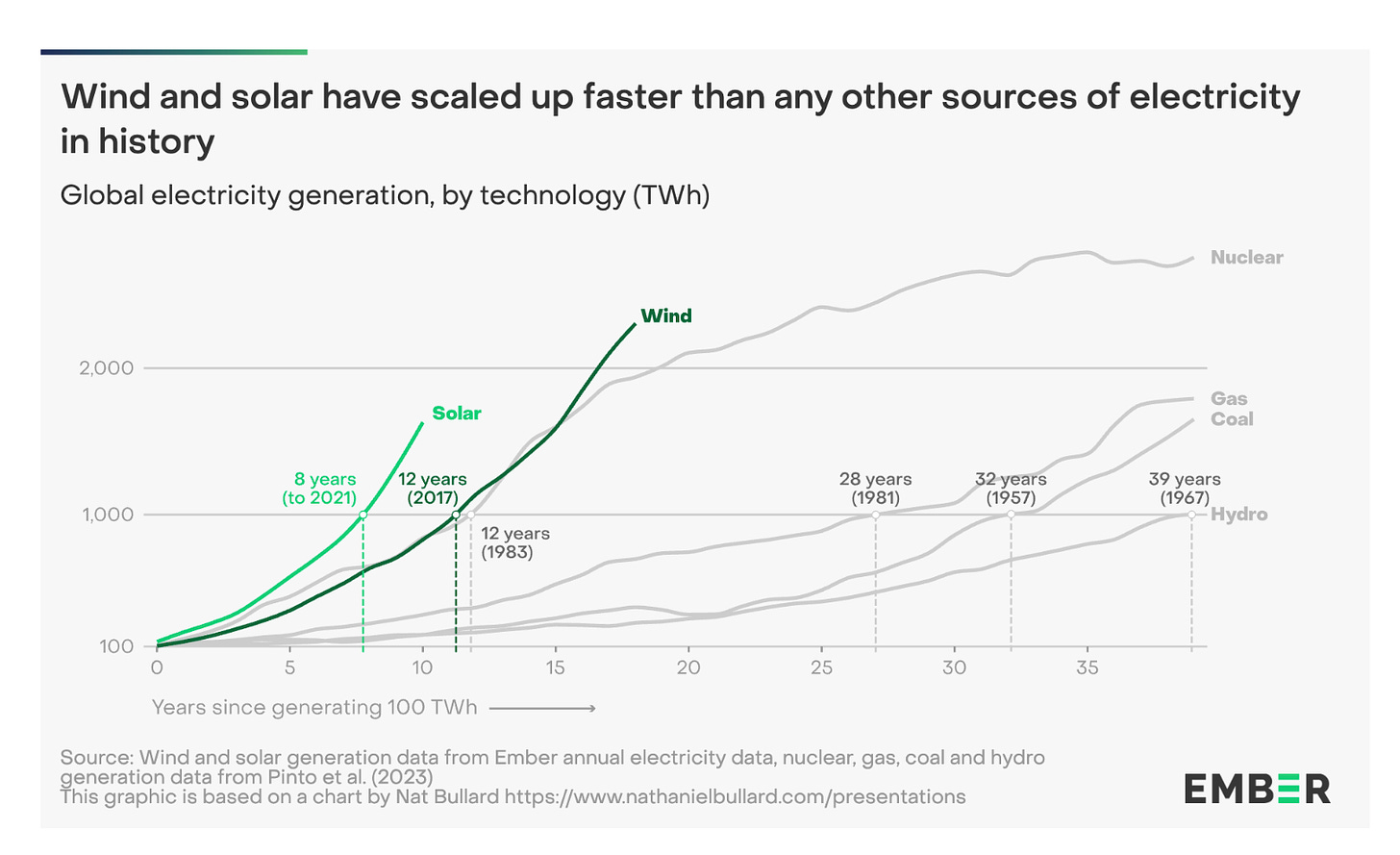

What we are witnessing is the most rapid take-up of a significant energy technology in history.

The response of Western politicians? Protectionism. Of course there are complex motives. They need to build coalitions to sustain the energy transition. They are worried about the CCP regime in China. They want to escape extreme dependence on imported sources of energy (though of course in the renewable space it is capital equipment not energy they are importing). But the more basic question is simply this. Are Western government and societies willing to prioritize the energy transition if it is not their drama, not their success story? Or, if the PV panels and the electric vehicles are from China, do other interests take priority?

In the European case one can see a compromise based on a balance between domestic and Chinese-sourced energy transition solutions. As Martin Sandbu has remarked there is at least the possibility of a grand bargain. In the case of the United States it seems increasingly clear that the energy transition as such is a second order concern and geopolitical confrontation and the struggle to form domestic coalitions, takes precedence. That is depressing. And it matters. But, as Ember’s data make clear, it is far from being a decisive obstacle. The global energy transition will go on anyway.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

I feel that the American protectionism is not just about protecting manufacturing of panels and vehicles. (It is.) The more subtle protectionist undercurrent is protecting Big Oil and the propaganda to the public of the high price of green energy. Thus, Europe is also caught in the trap.

What about the numbers that show China as the biggest user of coal? Doesn’t that offset the renuable good stuff?