Chartbook 283 Trump, trade, capital controls and the future of the dollar: the Lighthizer-Pettis connection

The dollar system as it currently stands is a lopsided thing. It almost provokes the question:

“How can a system persist in which more than half the world’s reserves and 80 percent of currency transactions are denominated in the currency of an economy that accounts for only 15 percent of world economic activity at Purchasing Power Parity? Surely, this story can only end with the “fall of the dollar”. America’s financial hegemony will recede like that of the British Pound Sterling, following the exhaustion of World Wars and the end of Empire.”

In a previous newsletter I coined the phrase Fin-Fi (Finance-Fiction) for this kind of teleological thinking about the dollar’s trajectory. I don’t use the term “fiction” to imply that the idea of the end of dollar hegemony is fanciful. I want merely to emphasize that we are dealing with visions of the future that are necessarily speculative and are governed by narrative logics.

We have a sense that proper stories have beginnings, middles and ends. We know how the dollar system started. We have been at its heights. Surely, therefore, there must be an ending. Fin-fictions of the rise and fall of the dollar, satisfy this narrative logic. Whether they actually fit the economics or politics is another matter.

If we look a the dollar right now, there are two lines of fin-fiction in play.

One focuses on the dollar’s global role, the use of financial sanctions in geopolitical rivalries and the risks that might arise to the dollar’s centrality, if America overuses its sanctions power. This encourages a focus on alternative payments systems, commodity backed systems and alternative currency combinations touted by the BRICS.

I’ve always been a skeptic. It seems implausible to suggest that such political creations can unhinge a currency network anchored in trillions of dollars of private balance sheets.

What I think is more serious are the tensions unleashed not by exceptional and discretionary sanctions, but by the ordinary operation of the dollar system - interest rate movements, currency shifts, the ebb and flow of capital. Compared to sanctions, this is where the real money is.

This is the subject of my most recent column in the FT.

I’ve been worrying about the ordinary operation of the dollar system for some time on Chartbook.

Chartbook 211 Bucking the buck

Chartbook 212 on the new petrodollar

Chartbook 213 Could a plunging Japanese Yen upset the US Treasury market?

Much of this, you might say, is simply the uneven and combined development of the world economy. Interest rates go up. Currencies and commodities go up and down. Nothing to see here. Nothing that would shake the system. Certainly nothing of geopolitical import.

But the dividing line between economics and politics is not set in stone. It is not a naturally given thing. Sanctions against Iran, for instance, are undeniably politically and geopolitically motivated. But what about pressure on EM currencies as a result of a shift in market expectations towards Fed policy?

What gets politicized and how, is a matter of the pressures that the system generates, the motives of different actors, the narratives they spin and the intellectual frames they adopt. The stories that we tell - whether in books, articles, newspaper op-eds, newsletters and twitter threads - are not innocent.

In a recent working paper for IFRI, Brad Setser gives a typically illuminating account of Sino-US financial relations. His writing is cool in tone and empirically rich. And at the same time it makes a crucial point. He shows how blurred the boundary can be between the political and the ordinary economic realm and how substantial reallocations of truly large amounts of money can happen, whilst modifying but not breaking the dollar system.

From the late 1990s China unilaterally established a competitive exchange rate peg against the dollar backed by capital controls. This was the frame - once commonly referred to as Bretton Woods 2.0 - within which it accumulated giant trade surpluses and large dollar reserves. In the 2000s, Russia emerged as a huge exporter of energy. It too ran rade surpluses backed by a tight fiscal policy. In 2008, as geopolitical relations soured, Moscow invited Beijing to join them in a bear raid on US Treasuries, offloading their dollar assets with a view to exploiting America’s financial embarrassment and demonstrating their financial clout.

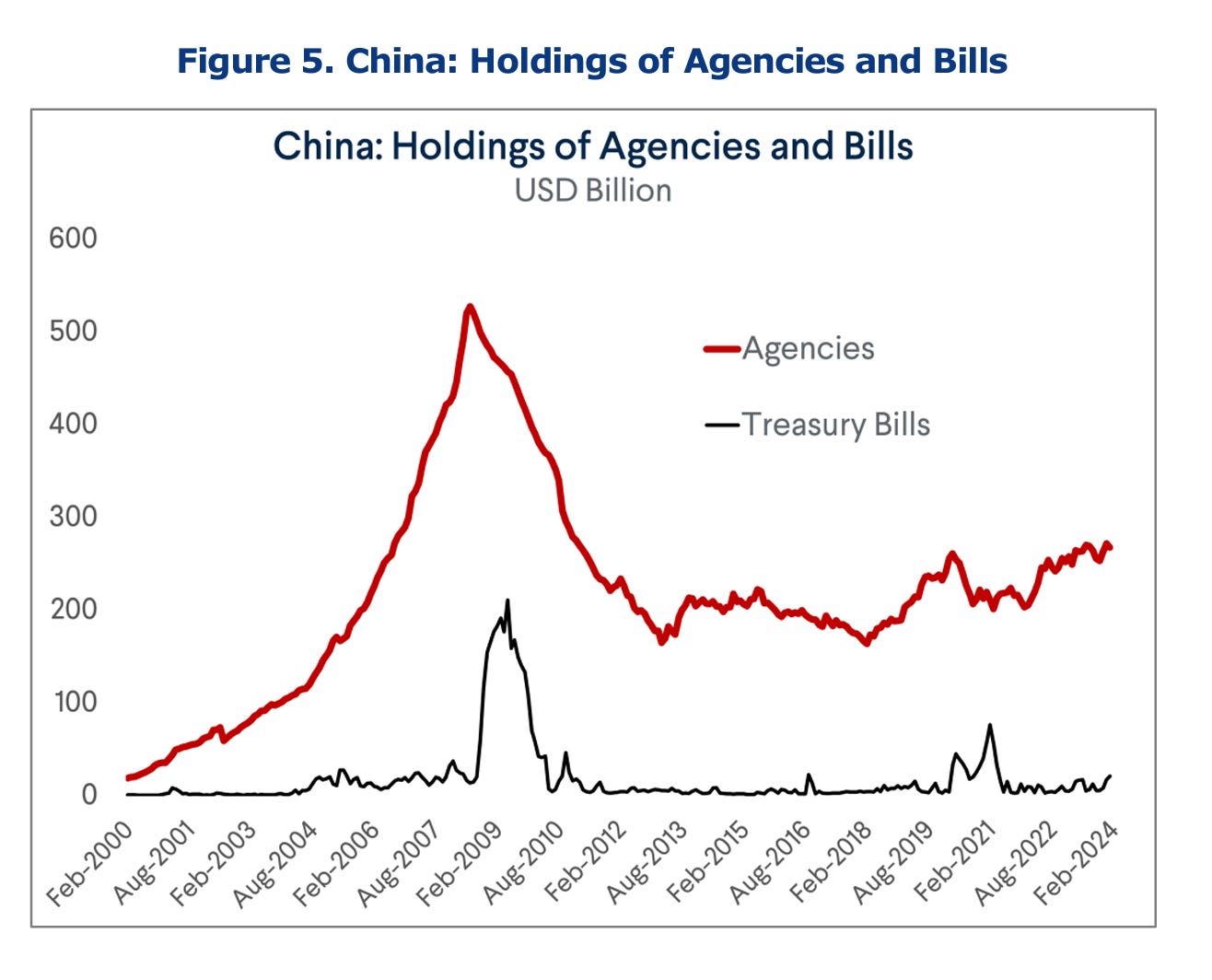

Russia did dispose of a large part of its most liquid dollar assets without causing even a ripple in a market that was at the time desperate for the security offered by US government debt. The Chinese politely declined. But, as Setser shows, they exercised considerable suasion over US policy-makers to ensure that their investments in government-backed mortgage agency bonds were protected.

Source: Setser IFRI

Beijing subsequently dispersed China’s reserve holdings, so that China’s central government exposure to US Treasuries has declined significantly relative to the size of the Chinese economy.

In the middle of 2008, China’s visible holdings of US financial assets were 30% of its GDP. By the end of 2023, that number was under 10% of China’s GDP. Not all of China’s exposure to US financial markets – then or now – is visible, but the broad trend has been clear. China did diversify and holds more modest reserves relative to the size of its economy than it once did.

Brazil has nowhere the weight that China disposes of in world affairs. But Brazil’s loud advocacy of alternative, non-dollar monetary systems galls Washington. It has less to do with sanctions and more to do with a general mistrust of American power which goes back to the Cold War and the fact that Brazil has repeatedly found itself on the wrong end of monetary policy whiplash. This was true in the 1980s and 1990s. It was true in the 2010s in the era of QE. In recent months, following the reversion of market expectations about Fed policy, the Brazilian central bank, like other EM central banks, was forced to intervene repeatedly. Whether or not talk of a BRICS currency has much reality, it serves to vent Brazil’s dissatisfaction with the status quo and to underline its non-aligned stance within the G20.

Structural change amplifies these pressures, as can be seen from the impact of US energy exports on the dollar. Previously, there was a negative correlation. Now as energy prices go up, the dollar strengthens. The dollar is starting to behave, at times, like a petrocurrency. This matters for the working of the “dollar system” because the positive correlation between energy prices and the dollar compounds the pressure on financially fragile importers of oil, which face the double whammy of rising oil prices and a more expensive dollar.

But financially fragile oil importers are not likely to trigger changes in the global currency system. Not are the efforts to evade sanctions by authorities in Beijing or Moscow, or Brazil letting off steam. As I argue in the FT piece, by far and a way the most consequential stresses generated by the operation of the dollar system are within the US itself.

There is a track record of this.

In the first decades of dollar dominance in the 1920s and 1930s it was US domestic politics that set the terms of America’s interaction with the world economy, and they did so ruthlessly. America’s impact on the world economy was dysfunctional - lending whilst imposing massive tariffs, pursuing a deflationary monetary policy that imposed huge stresses on the rest of the gold standard.

In the course of the Great Depression and WWII, American interest groups shifted their stance on trade and currency issues and the Roosevelt administration managed to tame America’s political economy to the point that they were able to fashion the GATT and Bretton Woods systems. But Bretton Woods was never the stable regime as which it is sometimes imagined. It was, from the start, fragile and contested. Wall Street always hated the onerous limitations on capital movement and found ways to work around them. By the 1960s, Bretton Woods was already under pressure and kept afloat only by the use of swap lines. As the USA came under pressure to deflate, the days of Bretton Woods were clearly numbered. Between 1971 and 1973 Nixon broke the dollar’s peg to gold and then to the other major currencies, embarking on a sharp devaluation. Why? Because he did not want to pay the domestic political price of stabilizing the system. Famously, he did not “give a shit about the Lira”.

In the 1970s a new dollar system emerged, based in large part of floating rates and a new network of global banking based around Wall Street, the City of London and offshore eurodollars. Its foundational moment was another US domestic turning point: President Carter’s choice of hard-money Paul Volcker as Fed Chair and the interest rate shock of 1979. Volcker sent rates sky-high and set the terms for the regime of monetary policy that operated for decades to come. Inflation was quashed, and interest rates eased down, year by year, decade by decade, from the extreme highs they reached in the early 1980s.

The initial impact of Volcker’s shock was dramatic. The surge in the dollar delivered a devastating shock to US exporters and triggered Latin American debt crises. By 1985 the dollar had appreciated by roughly 50 percent against all its major trading partners. The first Reagan administration took no action on currencies. But faced with an upsurge in protectionist lobbying, in 1985 the second Reagan administration, with James Baker as Treasury Secretary, agreed with the G5 at the Plaza Accords to work systematically to depreciate the dollar.

Each of these moments, moments that decided the development of the dollar system involved not inevitability but a situation of constrained choice, on the part of key decision makers in the United States. In the 1970s the future of the entire system was at times seen to hang in the balance. Other countries, notably West Germany, demanded action from Washington. But it was internal US politics that were decisive and they secured the continuation of a system oriented from 1970s onwards around internationalization and increasingly extensive use of easily available dollars.

In general, there is little doubt, that the world economy in general has benefited from a “weaker”, more freely available dollar. More liquidity and lower rates ease the flow of commerce and credit. The question is, how far can this go?

In the 1990s and 2000s, as America’s twin deficits - in the budget and on the trade account - became an entrenched feature of the world economy, there was a recurring fear that the US might be visited by a nightmarish, EM-style currency and debt crisis. Foreign holders of US assets would lose patience with America’s endless borrowing. They would panic and run for the exit, crushing the dollar and sending US interest rates sky-high.

Something like this is what Russia was trying to provoke in 2008. It has never happened. The dollar remains a safe haven currency. Even at times of stress in the US financial system, the dollar tends to strengthen. Even when issued in unprecedented quantities, US Treasuries remain the most indispensable, highly liquid “safe asset”.

As the Fed has hiked interest rates to deal with the price shock of 2021-2023, the anxiety in the current moment is not about a dollar collapse so much as about dollar dominance. This is causing stress around the world. But it is also causing tension in the United States, at least in one political camp.

Donald Trump is an inveterate advocate of a competitive, cheap dollar. This goes hand in hand with his preference for low interest rates and his crude mercantilist approach to foreign trade. Imports are “bad”. They are money “lost” to the US economy. Domestic manufacture is good. Exports are good too. A trade surplus means you are “winning”.

Robert Lighthizer, thought to be one of Trump’s closest economic advisors, is a famous hawk on trade, with a pedigree stretching back to the 1980s. In April this year, Politico ran a story highlighting Lighthizer’s advocacy of all means necessary to redress America’s trade imbalance in manufacturing, including, supposedly, a forced devaluation of the dollar.

“Currency revaluation is likely to be a priority for some members of a potential second Trump administration, mainly because of the viewpoint that [an overvalued dollar] contributes to the trade deficit,” said one former Trump administration official, adding that Lighthizer and his team are the primary advocates for the approach.

Alan Beattie in the FT, citing excellent economic arguments, dismissed this as bad economics and unlikely to work.

Then, a few days later, came the rumors circulated to the Wall Street Journal about plans within the Trump camp to subordinate the Fed to the White House. Making Trump part of the decision making process on interest rates is the key idea. If it were to come to pass that would certainly weaken the dollar. Whether a Trump administration could get the Congressional majorities necessary is an open question. Their efforts to plant radical Trump appointees on the Fed board did not succeed the first time around. But even an attempt to curb Fed independence in 2025 would shake the institution in a way we have not seen in more than half a century.

On May 13, in the next turn of the rumor mill, Lighthizer in the pages of the WSJ has declared himself against any subversion of the Fed’s independence and against efforts to lever down the dollar as in 1985.

“The global situation is very different than in 1985.” Lighthizer commented: “No policy adviser that I know of is working on a plan to weaken the dollar.” … “It’s a great accomplishment that America eventually got to an independent Federal Reserve system. The last thing I’d suggest is to do anything to change it.”

But, Lighthizer is more determined than ever that something must be done about America’s trade deficits. What he aims for is a system of balanced trade. Exports should be matched by imports. Anything else perpetuates fundamental structural disharmony. As Lighthizer has come to realize, trade imbalances are not just a matter of industrial “competitiveness”. They are the result of far wider systemic imbalances.

Economists still disagree with Lighthizer on deficits, which they see as the natural outcome when a high-saving country like China trades with a high-consuming country like the U.S. Lighthizer agrees that deficits reflect savings differentials, but not that they are natural. Rather, they result from other countries’ policies that suppress consumption and subsidize exports. An example: Germany’s early-2000s labor reforms which, along with the adoption of the euro, suppressed German wages and rewarded exporters.

If this sounds familiar. It should be. The WSJ attributes this shift in Lighthizer’s thinking to the influence of Michael Pettis, who with Matt Klein authored Trade Wars are Class Wars.

Yes, you read that right. The connection between Lighthizer’s brand of nationalist economic policy and the “Hobsonian” Pettis-Klein position has been made. Pettis this morning retweeted the WSJ article with an endorsement for Lighthizer’s position.

Whereas Lighthizer favors draconian tariffs to slash US imports and restore trade balance, Pettis favors an indirect approach that is even more far-reaching:

a “market access charge” on any country investing the proceeds of its trade surplus into U.S. assets such as Treasury bills. “Tariffs across the board punish everyone equally,” Pettis said in an interview. “Imposing a capital tax hits only countries with excess savings.” This amounts to reimposing capital controls, which the U.S. had largely abandoned by the 1980s.

Pettis elaborated his argument at much greater length in February in a full-length statement at Carnegie which argued for controls to be imposed on the American capital account.

To put it in a slightly more technical way, if the United States doesn’t control its capital account, it cannot control the gap between U.S. investment and U.S. savings, which in turn means it can control neither its trade account nor its overall savings rates. If the rest of the world wants to implement industrial policies that suppress domestic demand and force up their savings relative to their investment, and if they are freely able to export those excess savings to the United States by buying U.S. assets, the U.S. trade account and the U.S. savings rates must adjust to those inflows. This suggests that a more direct and focused alternative to tariffs is capital controls. If the United States were to tax capital inflows, or otherwise restrict capital inflows from surplus economies, then there would be no need for the U.S. trade account and its domestic savings rates to adjust to net foreign inflows. There would also be no need for import tariffs.

He then goes on to ask, how such a policy of capital restrictions would affect the global use of the U.S. dollar?

The U.S. dollar is the most widely used global currency mainly because of the depth, liquidity, and flexibility of U.S. financial markets along with the country’s relatively strong protection of foreign investment. This is another way of saying that it is the U.S. role as absorber of last resort of global excess savings (“consumer of last resort”) that accounts for the overwhelming domination of the U.S. dollar in global trade and capital flows.12 Restricting net capital inflows would reduce the global use of the dollar and move the world to one in which no currency plays the role that the U.S. dollar currently plays. But while this would benefit American farmers, workers, the middle class, and domestic producers, it would hurt three very powerful U.S. constituencies. The first is Wall Street, whose global dominance is underpinned by the global dominance of the U.S. dollar in trade and capital flows. The second is the foreign affairs establishment, who can use the dominance of the U.S. dollar to impose sanctions on countries that oppose U.S. geopolitical interests. And the third consists of large corporations that benefit from the easy transfer of investment out of the United States. This means that Washington must balance the long-term interests of the U.S. economy overall against the shorter-term interests of three very powerful constituencies.

Before we dismiss the idea of capital controls as completely outlandish, it is worth remarking that China, the world’s second largest economy, operates with a tight system.

Clearly, Pettis and I are maneuvering around the same set of issues. On May 13th, the same day that the WSJ article appeared that links him to Lighthizer, Pettis reacted to my FT piece with one of his trademark threads:

1/8

Adam Tooze is of course right to worry that any major adjustment in the global role of the US dollar is likely to be disruptive for the global financial system, but I think he, like others, grants too much agency to US control of the dollar.2/8

It is true that Washington and the Fed can affect the short-term performance of the dollar, both directly and by implementing industrial and trade policies that change the US role in the global economy. Ultimately, however, the outsized role of the dollar, and the…3/8

concomitant role of the US economy as absorber of last resort of global excess savings – and, which is the same thing, as global consumer of last resort – has created decades of distortions that have caused major trade imbalances, surging debt, rising inequality, and a...4/8

long relative decline in the role of manufacturing in the US economy. None of these is sustainable. Rising debt and declining manufacturing will themselves eventually undermine the credibility of the dollar as a safe asset.5/8

Tooze recognizes this: “The economics of this lopsided situation are ambiguous. The dollar’s reserve status supports a US current account deficit that favours US importers and creates markets for the rest of the world, but also skews the US economy away from traded goods.”6/8

One way or another this system, and the US role, must and will adjust, and the adjustment will inevitably be disruptive. The question however shouldn’t be whether or not we can postpone adjustment for another decade or two, but rather what form that adjustment must take.7/8

Because a world in which the US dollar and the US economy continues to play its current roles in accommodating deep structural imbalances is unsustainable, a major shift is inevitable and we can’t simply call on Washington to prevent any change.8/8

The issue should be whether Washington directs this shift unilaterally, directs it in concert with major allies, or waits until unsustainable pressures force a much more disruptive adjustment. It’s not whether things will change but how they change.

What is striking to me about this Pettis response, and where we profoundly disagree, are the words “unsustainable”, “inevitable” and “force”.

In fact, whether or not to politicize the existing pattern of surpluses and deficits is a choice. Though the existing dollar system, skews the US economy against manufacturing, the scale of the “skew” induced by trade is debatable. The idea that inequality in the United States is largely the result of international trade, or reducible to the China shock, is shared by both political parties, but that does not make it empirically convincing. Trade wars may have elements of class war about them, but the domestic arena - in areas such as taxation, welfare, education, public investment - not trade policy, is where the class war is won and lost, and where most of the redistributive action happens.

One can agree with Pettis that America with capital account controls would be a different place. Indeed, it would have to be a very different place for such a policy to have any chance of being successfully implemented. It would hobble Wall Street, after all. But to suggest that this will end deaths of despair, redress massive American inequality and restore manufacturing jobs, is to engage not so much with inevitabilities, as in a bold leap of macroeconomic faith.

I don’t fault Pettis for making that leap. It is in the logic of his long-standing argument. But by invoking “unsustainability” and “inevitability” and “forced moves”, Pettis understates the political choice implied by throwing his intellectual weight behind Robert Lighthizer. As Lexiteers learned to their cost in the UK, tactical alliances with the right-wing in the name of economic sovereignty, come with high political risks.

Furthermore, the risks here are not merely tactical. There is a deep social conservatism embedded in the view that insist on the priority of manufacturing as essential to the restoration of social balance in America. This sidelines other visions for healing the wounds of American society and shaping its economic future - the Green New Deal vision centered around non-traded care work, for instance. If the US had a more adequate welfare state and a better education system, would we be obsessing over the “China shock” the way that we are?

I read Pettis’s proposals, the “inevitabilities” that he invokes in his response to my FT piece, and his dalliance with Lighthizer, as symptomatic of the argument I am making.

The real challenge to the dollar system comes from the tensions brewing in America’s own political economy and the way those are being politicized in a new discourse of national economic crisis, a crisis which demands “whatever it takes” and which is fostering new and strange political alliances.

How the political ferment plays out, remains to be seen. A Trump administration, with Lighthizer at the helm of economic policy that took the idea of capital controls seriously, whilst running huge fiscal deficits, would be a genuine historical surprise! The wider global fall out is hard even to begin calculating.

As I said in the FT piece: “First under Trump and then Biden, US policymakers have blended industrial policy, trade policy, green energy and geopolitics into a potent nationalist formula. Adding the currency system into the mix would make for a truly explosive cocktail.”

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.