Last night, up close, on the barriers on Broadway barring the approaches to Columbia campus, I witnessed riot police crush protestors, driving them out of the way, pinning them against walls. Somewhat further away, on Amsterdam through the haze of drizzle and flashing lights we glimpsed what looked to be disheveled young people being herded into police buses.

It has been a while since I have been on a rough demonstration. Returning to the experience after many years was shocking and deeply thought-provoking. For me, the juxtaposition of the the blunt force deployed against demonstrators and the the themes I am normally preoccupied with, brought home an essential point: the strange multiplicity of ways in which the state manifests its power, but also the ways in which those hierarchies of power intersect and reinforce each other.

My mind was supposed to be on a very different aspects of state power - the multi-billion dollar aid package for Ukraine and Israel and the question of who gets which missile systems.

The other big policy questions on the Chartbook agenda are:

The scale of incentive schemes like the Inflation Reduction Act or the Just Energy Transition Partnerships.

The lurching moves in currency and capital markets brought about by the interest rate policy of central banks.

Let there be no mistake about this, all these have their coercive aspects. The mute power of money and the lack of it are all too real.

But then, after all the debate and talk of the last few weeks, last night, there in front of us on the street was the state manifesting in a primitive battle for control of space. Burly officers, shoving, pushing, man-handling, crushing protestors, climbing into buildings - a building I taught in on Monday - using what looked like medieval siege machinery, bodily hauling students off to police vans and cells, pinning their wrists with plastic straps.

In the main, this force isn’t lethal. But what you realize up close is that non-lethality makes it all the more direct, personal and bodily. After all, the whole point of a gun is that it is a “stand-off” weapon. You don’t get to close quarters. Cinema captures this distancing effect in the geometries of armed stand-offs.

Tarantino: Reservoir Dogs

The lethal, distanced threat of the guns serves to hold everyone, frozen, concentrated in place. Often, as a result, very little happens. An armed stand off is a time to talk. This was true of the only armed confrontation I have ever witnessed up close, the armed siege of a pub in Cambridge, one Sunday morning. That morning nothing moved for several hours. There was a deathly silence apart from the police loud hailer.

The policing of crowds we witnessed last night, is something very different. It is an intensely physical, sweaty, muscular business. This is state power exercised in the manner of a wrestling match or rugby scrum. One might also say that it has something in common with the herding of large-animals, except the animals are people, citizens, indeed.

The exercise of non-lethal but physically coercive power has its own tactical logic. It has its own economy. There is an entire industry of non-lethal means of coercion, with a global market-size of over $10 billion.

On the part of the practitioners, it is well rehearsed. The police clearly prepare for action, in mind and in body. Within the New York Police Department there is an extraordinary argument going on right now, as to whether there should be mandatory testing for banned steroids. The largest police trade union has filed a suit against the police-commissioner and NY mayor Adams to shield the police against excessively intrusive testing. Whether the riot police at Columbia last night were regular steroid users, I have no idea. But they certainly looked and acted “pumped”.

Up close, the concentrated aggression of a riot squad is dramatic.

Everyone else in the confrontation on Broadway was talking. Protestors shout slogans and hold placards. By-standers remonstrate with the police. If you lived above 114th street and did not happen to be at home when the police swooped, you had to plead to be allowed to cross the line and return to your own home. Those on the police-side of the barriers were simply locked in. Anyone leaving their home was treated as a potential threat and liable to arrest.

The riot police enforcing this order stand silently, in ranks, several lines deep. It creates an impression that is a strange combination of menace and insecurity. Why do these empowered people, in uniform with all the force at their disposal, need to huddle up and refuse eye contact in the way that they do?

They stand stoney faced even when addressed directly. They don’t talk to regular folks. They refuse any response until ordered.

The crowds opposite them are reduced to watching for twitches in their faces, signs of stress, "tells" that the police are about to move. Those doing the chanting try to see, which slogans produce a reaction. The NYPD smirked in response to “Quit your jobs!”. They seemed a little more disconcerted when the protestors shifted to “I don’t see no riot here. Why are YOU in riot gear?”

That was all too evidently true. There was no riot last night at Columbia any more than there has been at any other point. The violence came from the police side and it came at the invitation and request of the University administration.

My colleague at the FT Edward Luce is right. It was the adults not the students that caused the real disorder. It is the University administration not the student protestors who have seriously disrupted the end of term and examinations.

When the violence came last night, it was sudden.

When the sign came to force the passage of one of their vehicles, the police first formed up, moving close to the barrier, face to face with the protestors. The protestors formed a soft chain, many reversed, turning their backs to the police ready for what was about to come, knowing they would need to retreat under massive physical pressure.

On an order from their commander, the police pushed. They pushed hard. Very hard. They move fast, as quickly as their bulk and equipment would allow, maximizing momentum. The officers use waist-high steel barriers as plows to drive the protestors back and to pin them in side streets and against walls. Then, after the vehicle was through and the shouting and chanting of the protestors rose to an extreme crescendo, they pulled back and rearranged themselves again, across Broadway behind their barriers. The shouting and staring resumed.

The scene was static. But I would not be honest if I did not say that my stomach churned watching it. The sheer force of the movement, the relentless and sudden drive of the steel barrier against human bodies, moved the air.

***

The recent scenes have been campus protests. But it would be naive to imagine that this kind of coercion is confined to symbolic political protests with no broader, economic meaning.

In fact, once you witness it up close, you come to realize that this kind of non-violent physical coercion - the threat of being out-muscled in the crudest sense - is at the heart of our daily lives including in every workplace. Those of us who teach on locked down campuses have recently felt this very intimately.

When we say that corporate security "escorts" a staff member "off the premises", the implicit threat is of a physical confrontation.

When I ask to enter campus, but am refused, I might imagine that I have enough bulk and speed to get past the first barrier. But that gesture would only result in a pointless and unseemly tussle. To even entertain the idea is absurd. But why? At one level it is a physical calculation: Because there are more of the guards, they are bigger and muscling people is their job. But far more important is the sociology: because the confrontation would erase all the other significant markers of distinction and rank and privilege which 99.999 percent confer privilege and authority on me. Except in this case they don’t. I can’t get onto campus. And, once you think about it, the same is true for many other situations too.

For the sake of order, we are constrained and accept that we are constrained, policed, not just abstractly but physically, guarded, bounded, out-muscled. Only the exceptionally privileged rich and over-mighty escape this mundane regulation. The broader that privilege the more oligarchical and disorder a society is. In extremis oligarchs travel with their own bodyguards and create their own order around themselves, if necessary with privatized violence.

This elementary physical constraint is both an inferior order of power - defined both in terms of race and class and in terms of those who are subject to it and exercise this power. And yet it is also ubiquitous and essential. Its subordinate place in the broader order is itself a threat. If you end up on the wrong end of it, if you end up being muscled, then you risk disqualification. You risk an arrest record and that in turn will devalue all your credentials, your social and cultural capital, invalidate your green card, prohibit naturalization etc.

From the micro to the macro. It is by these same techniques and according to this same logic, on a much larger scale, that major strikes are policed. Looking back, the miners strike in Britain of the 1980s, one of the largest moments of class struggle in the late 20th century, involved demonstration after demonstration, in which men hurled their bodies against each other.

In the Lockdown protests in China in 2022 workers and security guards clashed body against body.

Since this is not war, since, unlike in Gaza no guns have gone off, no bombs exploded, after the clashes are over, you tidy up. And apart from some broken furniture and a smashed window, order and normality are restored.

But if you have witnessed these scenes, especially close up, you struggle to unsee and “unfeel” what transpired in those confrontation, the thud of bodies, the rush, the charge. The way the corner of a building became a pen for herding people.

You realize that, in the last instance, this is what the ubiquitous uniformed staff, cameras, doors, key cards, gates that we all take for granted, are there for. They create check points, barricades, they set the stage for what we all know would be, if it ever came to it, very unequal physical encounters. Most of the time this does not need to be made explicit. If you are in my position and that of the vast majority of the readers of this newsletter, this apparatus is mainly there to preserve our privilege, protect our property, to create the playground that is the university campus, even this week.

But that force is there, a blunt, crude, simple force of body on body. It is there in reserve. And the normality which Universities will now do their best to restore, confirms one further point: Almost always, there is only one side that wins this particular type of encounter.

Of course, through struggles and negotiation different social groups and individuals can work for better, more just, more equal, more open, more transparent bargains. But after confrontation, the ordering force is restored and it perdures. Right now, the NYPD will police Columbia campus until after graduation.

The only way to change that would be to take up the most radical of demands. In a revolutionary situation that means to challenge military hierarchy and command chain.

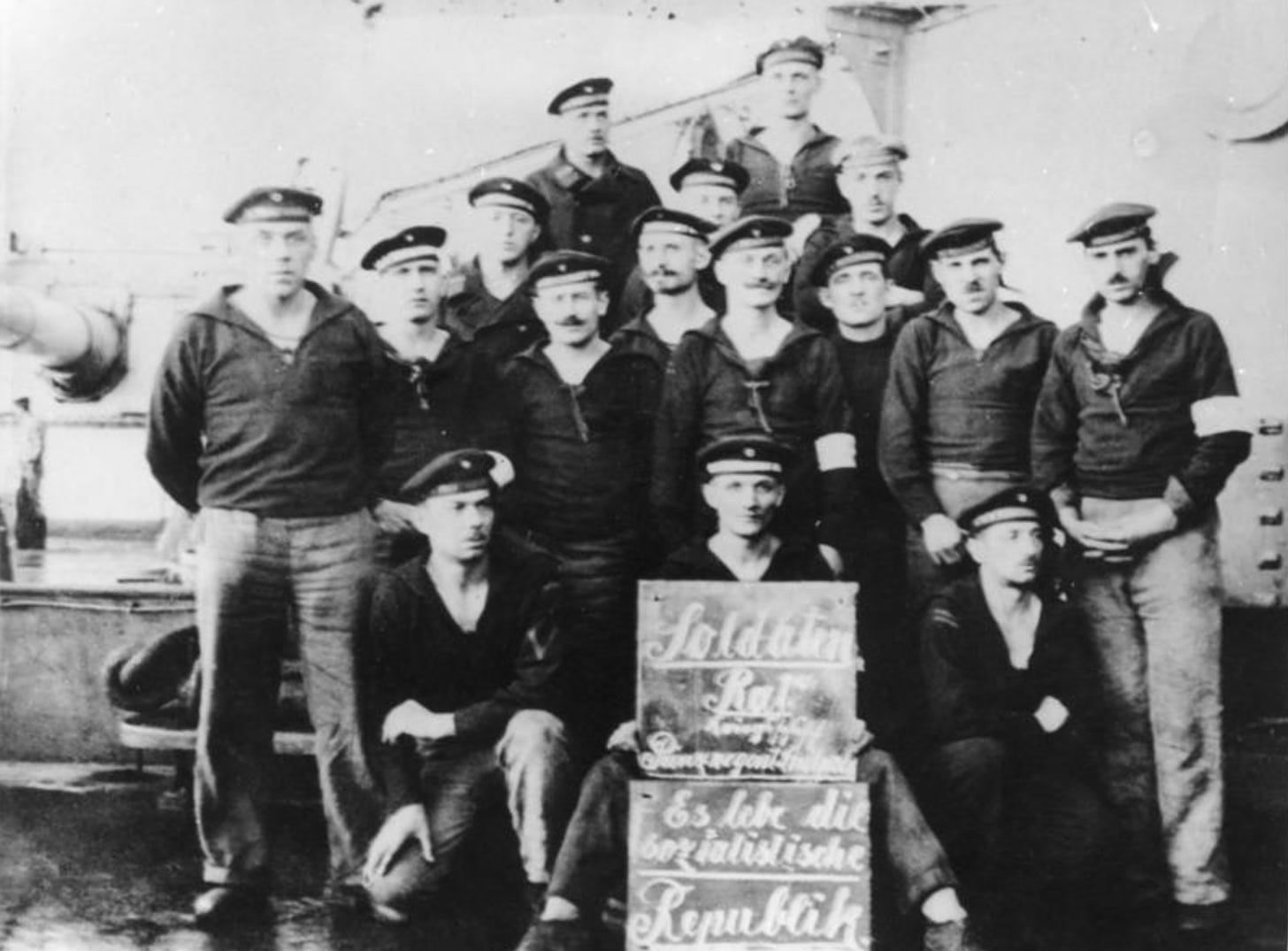

Kiel Mutiny November 3 1918

I cite this picture not out of revolutionary romanticism, but because this is literally the history I taught in Hamilton Hall, the site of the occupation, only the other week: how it is when you politicize the state’s coercive power that you really challenge its foundations.

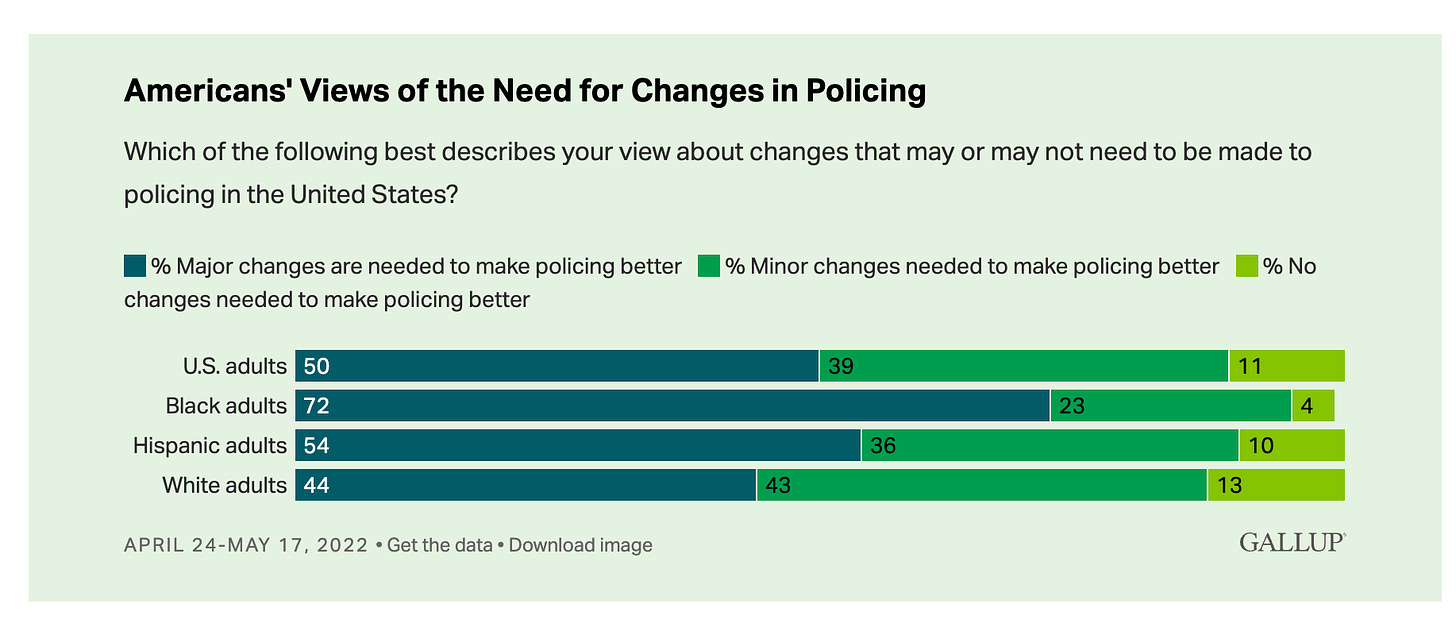

In the present moment the call is to defund the police and abolish prisons. Both demands strike many people as impractical. They poll badly. Authoritarian attitudes run deep. But reform of the police is quite another matter. Gallup finds solid majorities in favor of police reform with particularly strong support amongst the Black population who are most often subject to police violence.

Once you have seen the working of coercive state power up close, you realize that slogans like defund the police do one vital thing, something which should be essential for democracy, they challenge not just the bargain to which we agree - do we divest? are wages acceptable? etc - the radical slogans challenge the coercive power that ultimately sets the playing field on which we bargain.

If we want truly democratic politics and not merely a one-sided wrestling match, the question of what kind of safety we want and how it is to be secured, how we wish to preserve order, how we fund and equip what kind of police, must be on the table. If you simply “call in” and deploy the NYPD as it stands, the result will be the shattering, brutalizing experience that Columbia University, our neighborhood and our fellow campus at City College New York now have to come to terms with and recover from.

***

I've been part of protest encampments like this before, and there's always a debate among the protesters themselves about how confrontational or how law-abiding to be. And there are always people who want to go directly to the most aggressive law-breaking tactics right from the start, and these people generally aren't listened to right at the start.

But when the cops come in with with a heavy use of force, that dynamic changes. Suddenly, the protest leaders who counselled nonviolence, limited cooperation with the authorities and even the police, these people are made to look like fools and those who were for the most confrontational and even violent tactics are now seen as the "realists" who understand what we're up against. These people get a new hearing, and can lead the group wherever they want.

How does a protest escalate from peaceful occupation of a grassy area in the middle of campus to occupying campus buildings? It would be foolish to think that the police and administration crackdown didn't play a role in that decision.

Fantastic column.