Chartbook 277 The world is still on fire! (Summers & Singh) - the disaster of development finance in 2023.

2023 was billed as the moment in which the leaders of world came to terms with the scale of financing necessary for sustainable development.

For the last several years, world leaders have made big promises and laid out bold plans to mitigate the climate crisis and help poor countries adapt. They pledged that the World Bank would transform itself to work on climate change, and that the multilateral system would get new money and lend more aggressively with the resources it has, including to meet concessional needs. An agreement between creditors would provide debt relief to countries that most needed it. And where public money was insufficient, the multilateral system would be able to catalyze private investment in developing countries.

As a reminder the CGD helpfully summarizes the expert consensus as follows:

Additional spending of some $3 trillion per year is needed by 2030, of which $1.8 trillion represents additional investments in climate action (a four-fold increase in adaptation, resilience and mitigation compared to 2019), mostly in sustainable infrastructure, and $1.2 trillion in additional spending to attain other SDGs (a 75% increase in health and education).[3] The international development finance system should be designed to support this spending by providing $500 billion in additional annual official external financing by 2030, of which one-third in concessional funds and non-debt-creating financing and two-thirds in the form of non-concessional official lending. It should also help mobilise and catalyse an equivalent amount of private capital, implying a total additional external financing package of $1 trillion. MDBs should provide an incremental $260 billion of the additional annual official financing, of which $200 billion in non-concessional lending, and help mobilise and catalyse most of the associated private finance.

But, what happened?

Despite the bold rhetoric, 2023 was a disaster in terms of support for the developing world.

Capital did not pour into the developing world, to drive growth. It drained out.

“Billions to trillions,” the catchphrase for the World Bank’s plan to mobilize private-sector money for development, has become “millions in, billions out.”

These are not my words, or the words of some radical critic of neoliberal development policy. They are the words of a blue chip panel of experts - the so-called Independent Expert Group - appointed by India’s G20 presidency, headed by none other than Larry Summers. Larry Summers has been pushing the message of the report with the slogan - I kid you not - “The world is still on fire!”

Alongside Summers, his co-convener was NK Singh: President, Institute of Economic Growth, and Chairperson. The group members included Ms Maria Ramos: Chairperson of AngloGold Ashanti, and former Director-General of the National Treasury of South Africa; Mr Arminio Fraga: Former Governor, Central Bank of Brazil; Professor Nicholas Stern: IG Patel Professor of Economics and Government, London School of Economics; Mr Justin Yifu Lin: Professor and Honorary Dean of National School of Development at Peking University and former Senior Vice President & Chief Economist of the World Bank; Ms Rachel Kyte: former Dean of the Fletcher School of International Affairs at Tufts University and former Vice-President of World Bank; and Ms Vera Songwe: Non-resident senior fellow in the Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution and former Executive Secretary, Economic Commission for Africa. Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam participated in the group until 14 September 2023 when he was sworn in as President of Singapore.

In other words these are the global “great and the good”. Key figures in the construction of what we know as “global governance”.

As befits their role, the IEG went on to formulate constructive proposals for what should be done next. They returned, in other words, to the script which their own statement of the facts about 2023 so spectacularly disrupts.

Nothing wrong with making recommendations, of course. More action in transforming the global development architecture is undeniably necessary. It has been necessary for years. But let the import of their words sink in.

2023 was a “disaster” for the cause of global development.

When a panel composed like this one, talks about a “disaster” and flips the promise of public-private “blended finance” on its head to declare that we are not seeing public billions turned into private billions, but inflows of public millions overwhelmed by outflows of private billions, we should not continue with business as usual. We should pause. By returning so swiftly to the reform agenda, we risk glossing over and soothing the shock that should be unleashed by the events which their report characterizes so precisely.

What happened? What made 2023 into a disaster for development?

In an op-ed for Project Syndicate, Summers and Singh do not mince their words:

… World Bank shareholders have not raised capital, substantially changed financing practices, or taken other bold steps. The International Monetary Fund is on net withdrawing funds from the developing world; the idea of comprehensive debt relief has gone nowhere; and financial defaults have been avoided only by the moral default of slashing health and education spending. Setting aside the complex problem of climate change for a moment, world leaders haven’t even been able to tackle the simplest, most straightforward challenges. War, inflation, and poor governance have brought some of the poorest people – including in Chad, Haiti, Sudan, and Gaza – to the brink of famine, yet the international response has been slow and muted. This is both a humanitarian disaster in its own right and a symbol of our broader inability to act in the face of a crisis. If the world can’t even get food to starving children, how can it come together to defeat climate change and reorient the global economy? And how can the poorest countries trust the international system not to leave them behind if that system can’t address the most basic challenges?

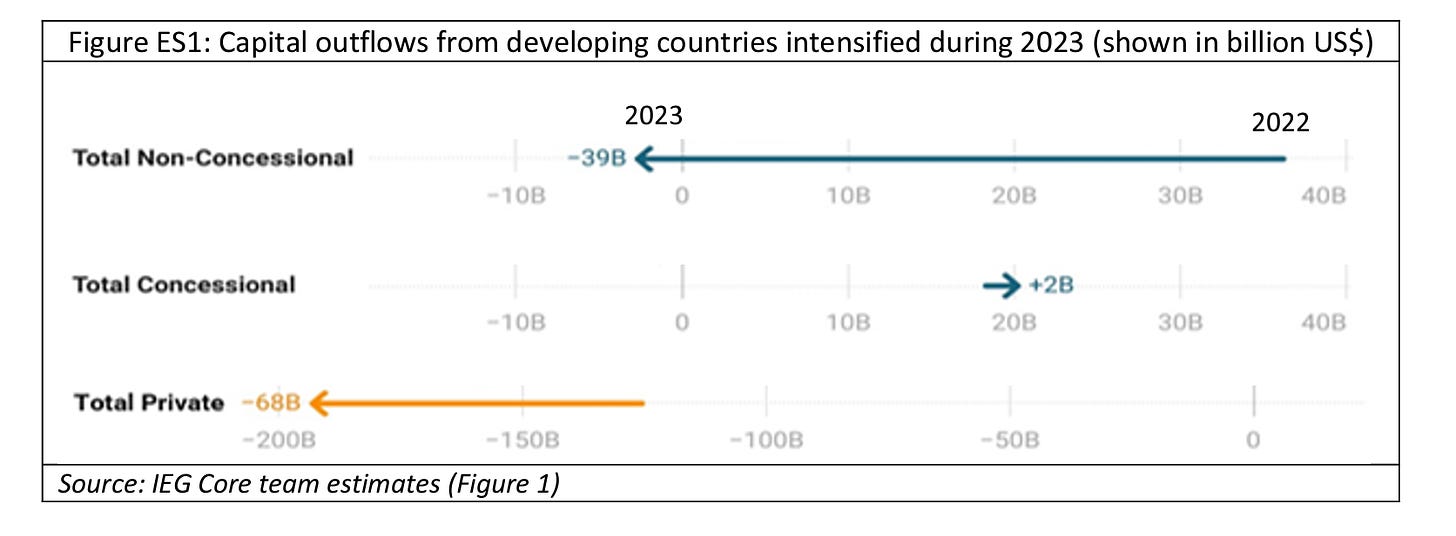

In financial terms, the drama is summed up in this understated graph.

What this shows is that money, both public and private, did not flow into the developing world but flowed out on a huge scale.

The pressure on the low-income world has been severe since the COVID shock of 2020 closed capital markets for most low-income borrowers. But what drove the intensifying squeeze in 2022-2023 was the switch back of capital flows unleashed by the reaction of major central banks to the price shock triggered by COVID. When the Fed raises rates, it drives interest rates around the world upwards and pulls capital back into the core of the US-dollar system.

As the IEG summarizes it:

Interest payments by developing countries on public and publicly guaranteed debt went from $99 billion in 2022 to $136 billion in 2023, due to sustained increases in interest rates in global capital markets, starting in mid-2022 and continuing through 2023 (Figure 2). High interest payments have sharply reduced the net transfer of resources to developing countries, limiting fiscal space for investments. Private capital continued to flow out of developing countries. No IDA-eligible country (the poorest of the low-income countries) issued a bond in 2023, and issuances by other EMDCs (slightly better placed emerging markets) fell sharply. As a result, bondholder net resource transfers were negative $161 billion from EMDCs in 2023, roughly evenly divided between interest receipts and net flows. Commercial banks withdrew an additional $42 billion in net resources in 2023. International financial institutions were unable to offset these resource outflows from EMDCs. Interest payments and fees from the IMF and major MDBs rose by $20 billion in 2023, reaching $37 billion. Repayment of principal rose by $14 billion. Consequently, net resource transfers fell sharply, turning negative for non-concessional flows to middle-income countries. Concessional flows through multilaterals held up, but recycled SDRs through the Poverty Reduction Support Fund and the Resilience and Sustainability Facility disappointed: net disbursements reached just SDR2.4 billion and 0.6 billion respectively in 2023.

The accompanying data highlights the shocking reversal in non-concessional lending by the so-called international financial institutions. The IMF alone contracted its lending by $21 billion, pushing it deep into net negative territory. The private sector contraction is so large that it has to be measured on a different scale. Flows were already negative in 2022 and became even more so.

This combination of flows should rob of us of any illusions about the actual operation of public-private development finance when it comes under short-term stress. The idea of so-called “blended development finance” is that modest amounts of public funds will be intelligently leveraged to generated larger private flows. What happened in 2023 was the reverse. With private funding accelerating its retreat from 2022 to 2023, non-concessional development funding was procylical. Far from increasing it not only decreased, but became net negative. And though concessional funding, to the poorest most-stressed borrowers, increased, it did so to a minuscule degree and was entirely powerless to off-set the overall rebalancing.

This is the reality that the powers that be want to “reform”. One might say it needs more than reform.

As the IEG remarks, one of the things that holds the current system in place is not its efficacy in promoting development, but its resilience. It bends rather than breaking in a dramatic fashion. As they put it:

One bright spot has been developing countries’ ability to avoid defaulting on their external debt. At the start of 2023, the IMF warned that 45% of low-income countries were at high risk of debt distress (IMF). In the event, only Ethiopia defaulted in 2023, missing a December bond payment.

But, as the EIG acknowledges, this resilience comes at a heavy price.

… it is important to recognize that continuing to pay high debt service has often translated into cutting back on health, education, and other critical public expenditures.

As the IEG spells out under such heavy financial pressure, investment and growth are bound to be lack luster.

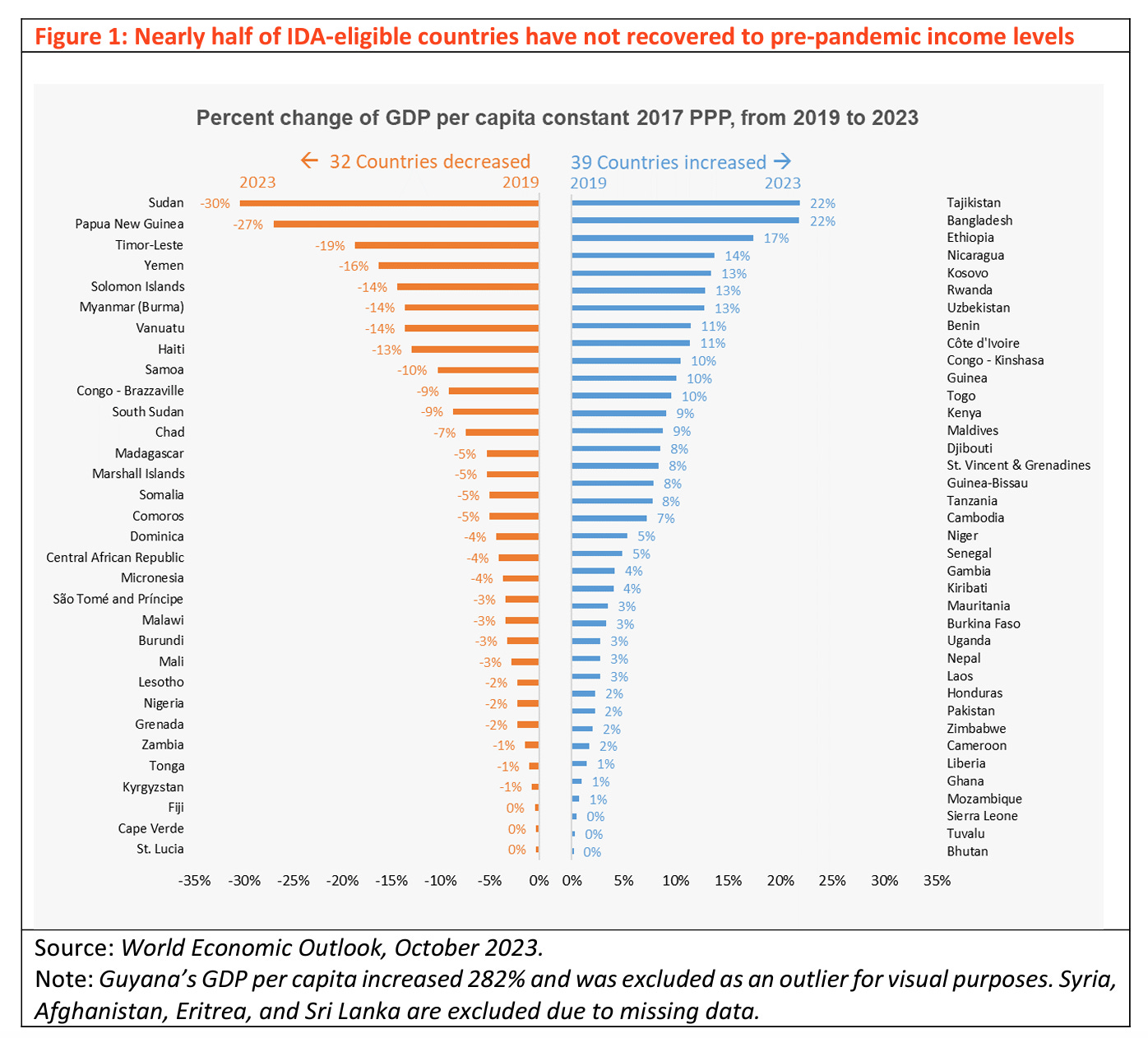

About half of International Development Association (IDA)-eligible countries failed to recover to pre-pandemic income levels. Per capita growth was anemic: 0.7% in Africa, 0% in the Middle East, and 1.5% in Latin America, partly because of weak investment levels. Currently, gross investment in most emerging market and developing countries (EMDCs) barely covers the depreciation of the existing capital stock; investment rates are in the range of 20-25% of GDP in all regions except Asia, where the average investment rate is 38% of GDP. The consequence of such low investment rates is that EMDCs will be unable to transition to green economies, to adapt to already-present climate change, or to sustain rapid growth, with dire impact on their own populations and on the global efforts to reach net zero.

This confirms the scarring shown in the IMF’s analysis I referred to in the last Chartbook 276 (at first unnumbered and then misnumbered … apologies dear readers!). For large parts of the world, talk of convergence is a bad joke.

Of course, you might respond by saying: development is a long-run process. It is tempting to downplay short-run fluctuations and one-off shocks. Classically, growth theory differentiates between the trend and cyclical component. We isolate idiosyncratic shocks. We can recover from temporary setbacks.

But drawing such sharp distinctions between long and short-runs is an abstraction. It is a simplifying intellectual maneuver that should not be confused with reality. As we all know, only too well, the long-run is made up of short-runs. The test of good practices and of good structures - long-run factors - is how they function in the here and now. Furthermore, one off shocks and “events” have long-run consequences. Upside shocks can put us on a new positive course. Negative shocks can throw us off course and may leave persistent damage.

And, when it comes to climate change and demographic shifts, we are under time pressure. The long-run is no longer very long at all. Every year, indeed every quarter counts. And a bad year leaves us with deficits that need to be made up, further intensifying the time pressure.

So when a group like the IEG says that 2022-2023 was a disaster for global development. We should feel the full weight of what they are saying. It will take years for the losses of last year to be made good. The risk is that the shock of 2023 ushers in a lost decade. There are not many reasons to expect things to get better soon. Certainly not unless there is serious action at the global level

Interest rates in the global core may not be heading back up - check out the excellent piece by Tej Parikh of the FT that I highlighted in last Top Links - but they do look set to stay higher for longer. Aid flows are increasingly focused on “global issues” e.g. climate and geopolitics e.g. Ukraine, rather than the ongoing global crisis of poverty and underdevelopment. I will address all of this in a future Chartbook. For now let us return once more to what happened in 2023.

What the shock of last year proves beyond question is that we don’t have a system that works and merely needs tinkering reforms. The status quo is from the point of view of the developing world profoundly dysfunctional. At moments of global stress it compounds disadvantage and entrenches underdevelopment and it does so to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars. At the macro level, with regard to the most basic questions - how much? to whom? when? - the system is simply not working. Quantities matter. As the CGDev website puts it on behalf of the IEG:

While there is room to disagree on whether the glass of Multilateral Development Bank reform is half-full or half-empty, what is important is the size of the glass. Our overall assessment is that the glass is still much too small.

In the final paragraph of their powerful op-ed, Summers and Singh adopt the vision of future historians.

We dare to hope that historians will look back at this week’s meetings (IMF/WB spring meetings 2024 that just concluded in Washington DC) as a moment when global leaders seriously addressed global challenges. The problem is not primarily intellectual. Blueprints like that of the G20 expert group we chaired on strengthening the MDB system abound. It is a problem of finding the political will to take on the most fundamental issues facing humanity.

Setting aside the actual disappointment of those gatherings - on which more in a subsequent newsletter - much as I appreciate the invocation of history it also gives me pause. What history should help us to do is more than just to inspire change and action. It should also help us to linger in the moment, or in the recent past. Not in a state of frozen melancholy, but to actually enable us to be in medias res, rather than in a state of continuous flight forward - fuite en avant.

What history first and foremost needs to do is record what happened in 2023 - the shocking facts and processes so powerfully and productively highlighted by the IEG team in their stocktake. What we need to do is to come to terms with that disastrous turn, to reckon with and acknowledge what happened: this is failure, failure on a spectacular scale, failure for hundreds of millions of people, failure driven by the core logic of our economic system - the pursuit of profit by huge volumes of private capital - a core logic that public institutions systematically fail to counteract.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

I dispute that it represents failure. My conclusion is worse than that -- the system is working precisely the way it was designed, because the colonialism and exploitation of the periphery never went away ...

i worked in washington in the development finance world in the late 70s but left the field after that. so for me the long run has arrived -- its 45 years since i was involved and it looks like really nothing has changed or really been accomplished. Development and not sustainability require domestic institution building first and capital second. that never happened and so we continue to have the imf and mdbs as perpetual motion machines whirling about in their own world and private capital interested in only returns now. For gods sake, look at the thames water disaster and the asset stripping going on in the us in the senior health care living sector (which i am involved with now). If the uk cant adequately manage private investment, how do you expect Ethiopia to do so?