The design-style created by the German Bauhaus school is today established as modernist icon, not to say cliché. Apart from the functional elegance of its designs, and the striking art many of its protagonists produced, Bauhaus acquired this standing in part through the way the political history of the school could be aligned with a conventional modernist narrative.

As narrated by both East and West Germany from the 1960s onwards, the Bauhaus - established first in Weimar from 1919 to 1925 and then in Dessau until 1932 - was a classic example of modernist enlightenment that was brutally cut short by Hitler’s Nazi dictatorship. Inspired to heal the wounds of industrial civilization and to open the path to a democratic aesthetic and form of life, the school propagated a holistic understanding of art and design. Early exponents pushed an abstract, constructivist aesthetic. Walter Gropius speculated about giving architecture and construction a machine-like industrial logic. Under the leadership of Hannes Meyer from 1928 onwards the social-mission of Bauhaus came even more to the fore.

Unsurprisingly, the project was an early victim of Nazi education policy in the state of Thuringia in 1932 and then at the national level in 1933. Many of the leading Bauhaus figures would eventually go into exile. Bauhaus-students Otti Berger (1898-1944), Eva Busse (1909-1942), Friedl Dicker (1898-1944), Lotte Mentzel (1909-1944), Zsuzsanne Banki (1912-1944), Elza Hirschl (1908-1942?), Senta Schlesinger (1898-1943), and Hed Slutzky (1894-1943) were murdered at Auschwitz.

After the war the spirit of modern German design was revived in the West by the famous Ulm school of industrial design (1953-1968). Its founders included the Swiss Max Bill who was a Bauhaus student and Inge Aicher-Scholl and Otl Aicher, who were linked, by way of Inge’s sister Sophie Scholl, to the White Rose anti-Nazi resistance movement.

As a canonical lieu de mémoire for global modernism, Bauhaus, truly came into its own with a retrospective exhibition hosted in Stuttgart, one of the industrial centers of postwar West Germany, in 1968. According to art historian Iris Dressler, the show with the programmatic title - 50 years of Bauhaus - was a sensational success, traveling to eight museums—in Europe, the United States, Canada, South America and Asia - and attracting more than 800,000 visitors in total. From 1974, a reduced version of the show put together by Germany’s Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen (Institute for Foreign Relations) toured the globe for a further eight years. The stakes were high:

The title, 50 years of the Bauhaus, already ascribes an unbroken continuity to the school—which, as is well known, existed for only 14 years, and in his opening speech the German Federal Minister for Building and Urbanism, Dr. Lauritz Lauritzen, claimed: “The Bauhaus … has significantly contributed to the cultural philosophy of a state designed (to be) democratic and of a democratic society. It is unthinkable without the democratic constitution of the Weimar Republic,” which, as he went on to explain, failed not for political reasons but due to the lack in Germany of an authentically liberal, open society. “The Bauhaus was of global vibrancy. … Without any national hubris one can say that it is a German contribution to culture and civilization in this world of the twentieth century, a contribution to the humanization of the technical century.” He then added: “The men of the Bauhaus who left Germany kept the spirit of German humanism alive in their exiles.”

As Dressler remarks, the exhibition said nothing about the activities of the Bauhaus students who were not forced to leave Germany. Indeed, the entire exhibition was a complex exercise in self-fashioning.

As Dressler has shown, Herbert Bayer, the designer of the 1968 exhibition was a case in point. After graduating from the Bauhaus in 1928 he joined the German edition of Vogue magazine and then enjoyed a successful career under the Nazi regime. Between 1933 and 1936 Bayer was responsible for several high profile design commissions, including major international exhibitions, work which features in the catalogue of MOMA today. Bayer only chose to leave Germany in 1937, when to his consternation his work was included in the degenerate art exhibition. Starting in the late 1930s, Bayer made a successful career in the USA being a favored collaborator of MOMA and also completing striking work for the American war effort. In the 1960s, as he established himself as one of the canonical figures of the Bauhaus legacy, Bayer rewrote his past. As Dressler reveals. In a 1967 monographic catalogue Hebert Bayer carefully edited the illustration of work he had done in 1936 for ADEFA, the German-Aryan textile industry, whose aim was to push Jewish manufacturers out of the German market. In the 1967 edition Bayer erased the name of the Aryan lobbyists from both logo and text. Moreover, as Dressler points out he manipulated the date, claiming the poster was designed in 1930—that is to say, before the take-over of the Nazi regime—although ADEFA was founded in 1933.

In Bayer’s case this pattern of collaboration was likely a matter of sheer opportunism. In the case of several leading Bauhaus figures, including Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe, there is little doubt that their totalizing visions of aesthetic control and creation shaded into an infatuation with total power.

Fritz Ertl, an Austrian, who studied at Bauhaus between 1928 and 1931 seems to have been a Nazi by conviction, joining both the party and the SS in 1938 immediately following the Anschluss. He would rise through the SS ranks becoming a member of the new construction management team at the Auschwitz already on 27 May 1940, when the camp was little more than a POW facility. By 1942, at the massively expanded camp, he would rise to become deputy chief of the SS Central Planning and Construction Office.

Full-blown academic revisionism on the history of Bauhaus in the Nazi regime was initiated in 1993 with the collection edited by Winfried Nerdinger (ed.): Bauhaus-Moderne im Nationalsozialismus. Zwischen Anbiederung und Verfolgung, Prestel Verlag, Munich 1993. Thirty years later, any sense of clear boundaries has dissolved. So much so that at a recent conference on Bauhaus and National Socialism, Christian Furhmeister was moved to ask: “Which image of the Bauhaus, which understanding of Modernism, and which concept of National Socialism are we even prepared to bear?,”

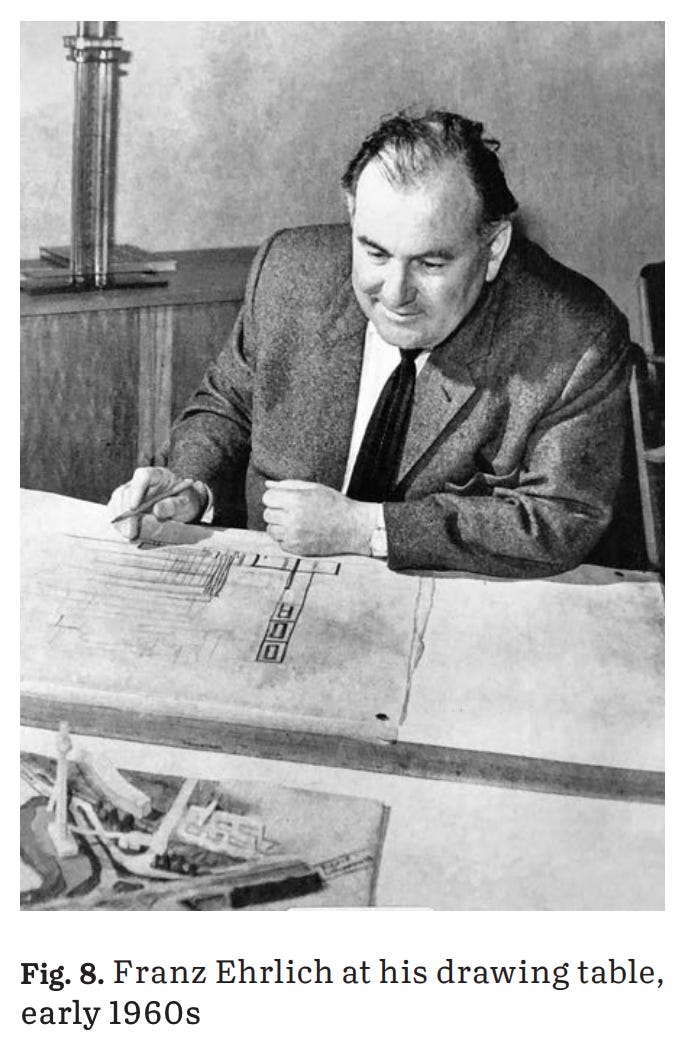

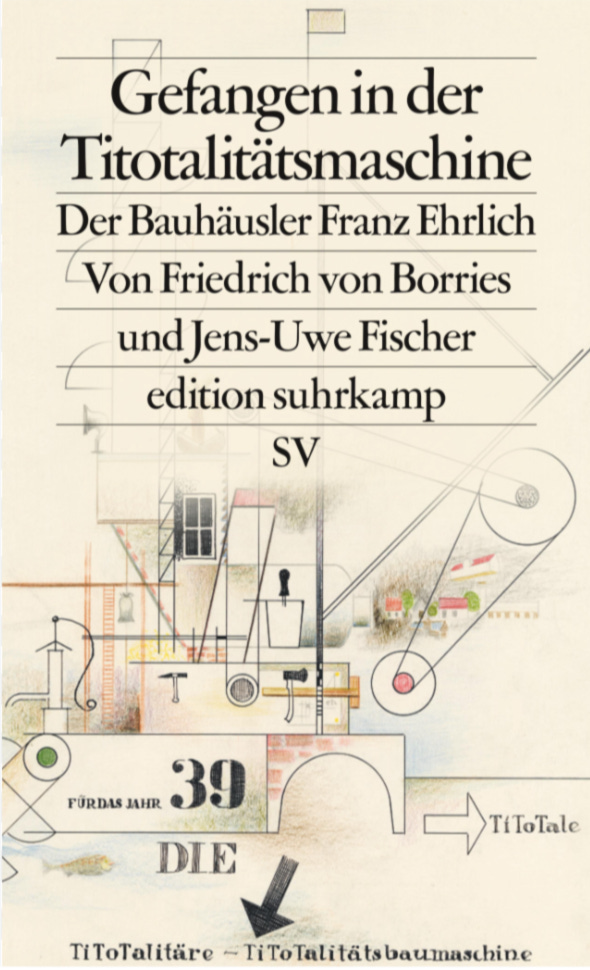

In Gefangen in der Titotalitätsmaschine, their remarkable biography of the Bauhaus-trained designer and architect Franz Ehrlich, which appeared with Suhrkamp in 2022, Hamburg historians Friedrich von Borries and Jens-Uwe Fischer have unearthed an even more astonishing Bauhaus trajectory.

On Borries and Fischer’s telling, the defining fact about Franz Ehrlich was that he was a self-made man. Born in December 1907 into a working-class family in Leipzig, he was one of the youngest and poorest students ever to attend the hallowed halls of the Bauhaus. Without a high school diploma (Abitur), Ehrlich was excluded from College, but he was fascinated by one of the early Bauhaus posters he spotted on the Leipzig train station platform in the middle of hyperinflation in 1923. Having compiled a collection of drawings in 1927 he tramped to Dessau and was accepted on the say so of Walter Gropius.

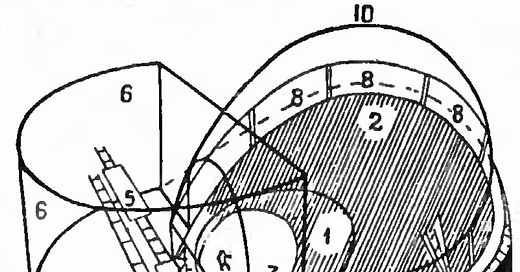

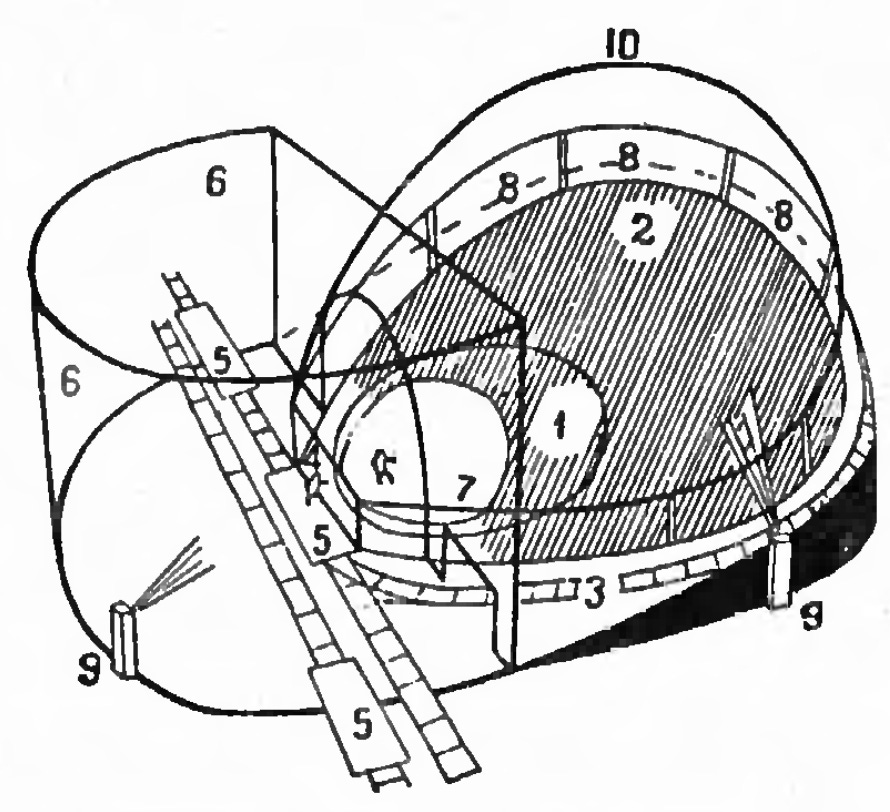

He would go on to take courses with Josef Albers, Wassily Kandinsky’s on form theory and drawing, and Joost Schmidt’s lettering course. He also attended courses offered by Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, and Oskar Schlemmer. He was the student representative on the Master Council. On the reading of Borries and Fischer, the most influential work that Ehrlich did at Baushaus were models for the so-called Total Theatre project for Erwin Piscator designed by Walter Gropius. It was to be a space that enabled complete control of the audience’s aesthetic environment, one of the moments where, according to Borries and Fischer, the Bauhaus vision shaded into totalitarianism.

Ehrlich’s student days were not plain sailing. By 1930 he was one show away from completing his Bauhaus degree. Whether he ever actually received his diploma would remain disputed until the end of his life. The headstrong young designer left school into the teeth of the worst economic crisis in history. Bouncing back and forth between Berlin and Leipzig he scratched a living on advertising design work. Politically, he had long been associated with the youth wing of the Social Democrats. After 1933, whilst still working as a designer, through his brother he fell into contact with an underground Communist opposition group and took charge of designing and producing a clandestine newspaper. Security was lax and in the summer of 1934 the Lepzig group was arrested. In 1935 Ehrlich was sentenced to three years. Though prison conditions were tough he was able to work in the wood-working shop and to continue painting and drawing. That changed drastically when rather than being released, in September 1937 he was transferred by the SS to Buchenwald camp.

In September 1937 the notorious camp was no more than six weeks old. Ehrlich received prisoner number 2318. By the end of the war, 100 times that number would be imprisoned and over 33000 would be killed at Buchenwald.

On arrival at the camp Ehrlich was assigned to the quarry. This dangerous work could easily have been a death sentence. What saved Ehrlich was his status as a political prisoner. Under brutal SS oversight, much of the day-to-day functioning of the camp was delegated to the prisoners themselves, under the so-called “kapo” system. The SS liked to play off “common” criminals against the “politicals”. But at the time that Ehrlich arrived at Buchenwald the politicals had the upper hand. Thanks to his connections he was assigned to the carpentry and cabinet-making department and from there was moved to the construction office.

Ehrlich thus became part of the economy of exchange that kept skilled, politically-connected prisoners in the concentration camp system alive. Amongst Ehrlich’s Buchenwald commissions were the interior of the commandant’s villa, which caused a sensation in SS circles.

Franz Ehrlich: Design for a representative hallway with fireplace and staircase for the villa of a SS leader in the Buchenwald concentration camp, undated, 1938-1941. Cited in Klaus Tragbar, “From the Bauhaus to Buchenwald and to Berlin: Anti-fascism and Career in the Life of Franz Ehrlich”

One of the interior design challenges Ehrlich faced was to find a place in which to display an object which was allegedly the shrunken head of an executed inmate, which had been gifted to the commandant of Buchenwald Karl Otto Koch by the SS guards.

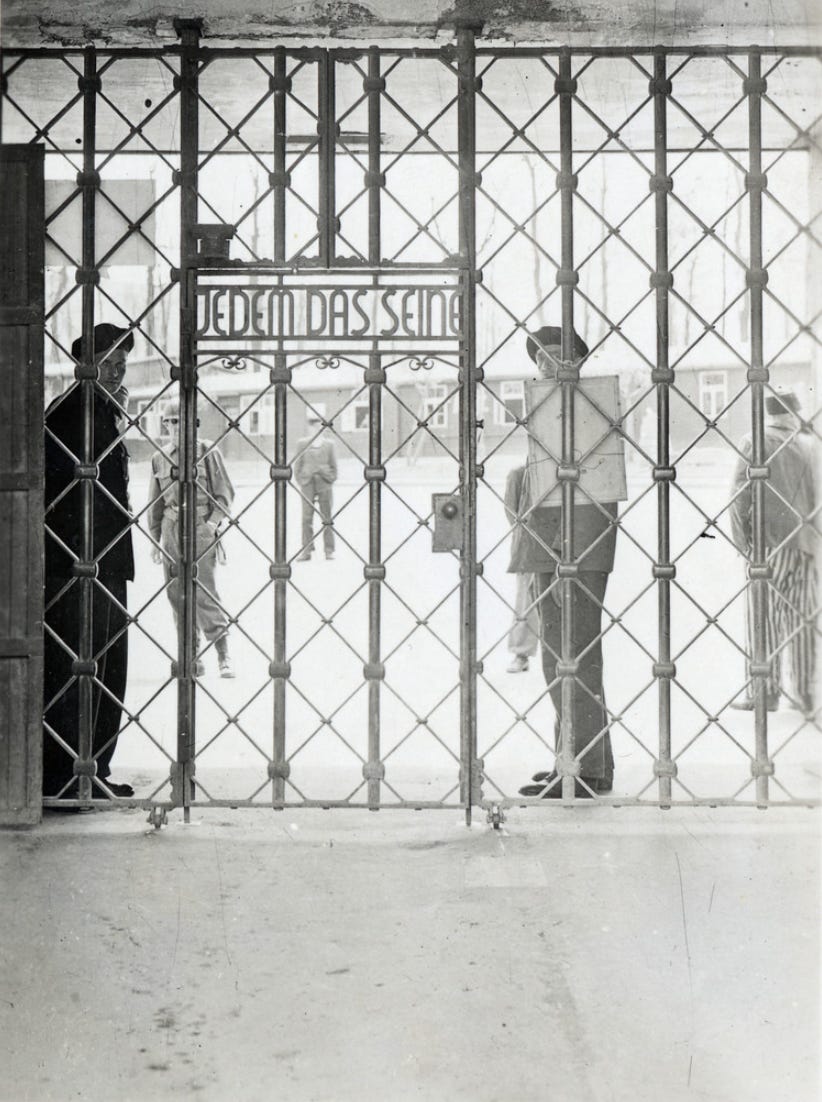

Whilst in his interior settings, Ehrlich accommodated the SS taste for rustic style, when he was asked to fashion a decorate plaque for the camp gates, Ehrlich reverted to a more modernist style. The sans serif typeface Ehrlich conceived for the motto - Jedem Das Seine (To each his own) - bears the hallmarks of the 1920s.

Camp gate after liberation in April 1945. Collection: USHMM

Buchenwald would define the rest of Ehrlich’s life. So what happened next is both decisive and obscure. In October 1939 he was released from detention and allowed to resume something like an ordinary life. But rather than distancing himself from the camp, Ehrlich settled in Weimar, married his devoted partner Elisabeth Haak, and carried on working at the SS design office at Buchenwald. Then, along with several of his superiors from Buchenwald, Ehrlich transferred to the SS head office in Berlin, thus joining the administration of the overall SS economic operation and concentration camp system, run by Oswald Ludwig Pohl. One of Ehrlich’s commissions was to design the conversion and restoration for Pohl’s personal residence. For the first time, Ehrlich and his wife were able to begin what he seems to have craved throughout his life, a comfortable, dare one say, bourgeois existence.

Was Ehrlich coerced? As a former concentration camp prisoner, in the Nazi regime he was perpetually on remand. Had he come to accept in 1940 that there was no alternative? Ehrlich in later accounts would insist that he never lost faith in the socialist movement. In his new role in the SS office, he claimed to have continued as a linchpin of the survival and resistance network that operated across the camp system. He was now in a position to commission work, which was what kept prisoners alive.

After 1945 no one survived who could attest to Ehrlich’s role in detail. And there is another darker possibility. Several of his superiors from Buchenwald, men who knew Ehrlich capabilities, went on to do significant work on the SS-camp system throughout Eastern Europe. Given these connections, what are the chances that he managed to avoid involvement in further concentration camp construction? As Friedrich von Borries and Jens-Uwe Fischer admit this is a question that is purely circumstantial, cruel and inescapable.

In any case, whatever his personal stance, Ehrlich had at this point clearly become part of “the system”. And this extended to his domestic life. Even the Ehrlich’s apartment was furnished with chairs he had designed for the SS at Buchenwald.

In any case, the Ehrlich’s phase of stabilization lasted only for a while. As the war intensified, Nazi objections to political prisoners serving in the Wehrmacht were lifted and in February 1943 Franz was drafted. As befitted his status as a political prisoner he was assigned to the legendary punishment division 999 then serving in occupied Greece.

Once again Ehrlich found a way to survive. Once again he would claim to have been involved in resistance - this time a conspiracy to assassinate the divisional commander and join up with the Greek resistance. The conspiracy was exposed. Its leaders were executed. Ehrlich was not amongst them. In fact, he was promoted. By the end of the war he had earned an iron cross (second class). The irrepressible Ehrlich was, yet again, making something of himself.

Having surrendered to the Yugoslavs in May 1945, Ehrlich was once again to the fore, this time as a credentialed anti-fascist leading so-called reparations reconstruction work. Or at least so he claimed. That accounted for his early release from captivity in the spring of 1946 and his return home to the Soviet-controlled zone of Germany, where he promptly joined the Communist Party (SED) and applied for and gained official recognition not just as a victim of the Nazi regime, but as a militant “anti-fascist fighter”.

Ehrlich’s claim to hold a Bauhaus diploma was suspect. He had gained a lot of experience as a designer and architect, but for a client, the SS, he would rather not mention. His political credentials were his strongest card and he played it for all it was worth. Rather than lying low, Ehrlich embarked on a career as a noisy exponent of architectural and design politics in the socialist GDR. At various times he was assigned roles overseeing reconstruction of Dresden and the design of the GDR’s first socialist city, the town that would later become Eisenhüttenstadt. At the height of his influence in 1950, Ehrlich was appointed as the chief architect of the GDR’s first five year industrial plan.

We are planning (Poster) Franz Ehrlich 1948/1949 Source: Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau (I 3867 G)

But despite these many openings, Ehrlich’s career never fully took off. He did not work well with others. He was beset by rivalries. He was bad at managing, preferring to think of himself as an inspired source of creative ideas. Though never an out and out modernist, he found himself on the wrong side of criticism from the socialist realists. The early SED was wedded to Stalinist style and denounced Bauhaus. In early 1950s, Ehrlich came close to being purged. Another Buchenwald inmate close to party boss Walter Ulbricht remembered Ehrlich’s role in the SS design office and questioned his bona fides. But once again Ehrlich got lucky. He had declared his wartime role to the SED on entry. And ironically, it was Ehrlich’s accuser who was purged. In a political scene dominated by comrades who had spent 1933-1945 in Moscow, claiming rank on the basis of your record in Hitler’s camps could easily backfire.

At this point it will come as little surprise that Ehrlich also has a Stasi file - both as an object of surveillance and as an informant. He was recruited under the codename “Neumann” in February 1954. He may well have been under pressure. Not only was there the issue of his SS collaboration, but he was connected to a party faction that had made a failed bid to unseat party boss Walter Ulbricht. Ehrlich, as ever, tried to make the best of it, offering the Stasi a sketch map of the GDR’s cultural scene, in the Bauhaus style, in which he positioned “Ich” - himself - at the very center.

Source: von Borrie and Fischer

Meanwhile, Ehrlich looked for jobs. His greatest architectural achievement was the GDR’s first radio studio. His most consequential design was for the Institute for Cortico-Visceral Pathology and Therapy - a quack neurological theory popularized in the Soviet bloc by Ivan Pavlov. As Ehrlich’s health deteriorated, he spent more and more time in the sanatorium he had himself designed.

Ehrlich’s most lucrative commissions, for the GDR as for the SS, were luxurious interiors, notably for the GDR’s trade mission. These were dismissed by the GDR’s artistic establishment, but they showed off socialist swank and they afforded Ehrlich the chance to travel. Between 1967 and 1984 he decorated trade offices and embassies in Belgrade, Prague, Helsinki, Bucharest, Budapest, New Delhi, Cairo and Düsseldorf. The last major building in which he had a hand was the Chamber of Foreign Trade of the GDR in Brussels, finished in 1973.

But where Ehrlich ultimately made his largest impact was in furniture design. It was Ehrlich that created one of the most popular modernist furniture sets of the GDR, the 602 series. Today, authenticated pieces from GDR production go for almost $2000 on 1sdibs. A rarer Ehrlich lamp is listed at in excess of $15,000.

In the GDR, it took a while for this mid-century style to break through because the first head of state, Walter Ulbricht, was an apprenticed carpenter who had little time for modernist experiments. It was not until Ulbricht was replaced by Honecker that the GDR could fully appropriate the Bauhaus legacy, enabling Ehrlich’s status to be further upgraded, by way of insertion into a socialist narrative of modernism’s origins. In his old age, Ehrlich had become a minor establishment figure, an old comrade who could be forgiven his occasional outbursts about the industrial ugliness of the so-called Plattenbauten, the prefabricated concrete apartment complexes, which his furniture helped to beautify.

How, von Borries and Fischer ask, does one make sense of such an extraordinary career? Insofar they offer a single answer it lies in the juxtaposition of two contrasting moments. One is Ehrlich’s early work on Gropius’s total theater design. For Christmas 1927 with his friend Heinz Loew, the two students, as a joke, presented Gropius with a sculpture they entitled in Dada style Ta-Ti-To-Tal-Theater, labeling it with warnings signs, including the telling “Emergency Brake”.

Twelve years later, on his release from Buchenwald, Ehrlich sketched another fantastical machine with a similar title - the TiToTalitäre Ti To Talitätsbaumaschine - which decorates the cover of von Borries and Fischer’s fascinating biography.

It was a total machine, made up of imaginary and real parts. An echo of his earlier work but now no longer merely as aesthetic caprice, but as a reflection on the horrifyingly surreal reality in which he was enmeshed.

How does one survive, live and act in such a world? Von Borries and Fischer suggest to us that Ehrlich’s life is an exemplary case precisely for its ambiguities, for the tensions it reveals in the modern conditions between conformity and autonomy, truthfulness, commitment, compromise, deception and self-deception. Ehrlich’s grandiloquence tests our credulity and our trust, but also our sense of self. How might we have acted? How do we act in our moment? Do we trust ourselves?

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Thanks Adam, I am amazed how you dig up storries like this one. He seem not to feature in any of the German media not even die Zeit

His lige’s storry would be worth a serious movie, so much grey and European history

Fascinating! Who knew? Thanks