Chartbook 273: Feeding the world, whilst "sparing land"? Debating the rise of modern Brazilian agriculture.

The emergence of Brazil as a huge net exporter of foodstuffs is one of the most dramatic stories of recent economic history. If there is one country that can claim to feed the world, it is Brazil. It is not the world’s largest producer of food, or even the largest exporter. But it has the largest net trade surplus in foodstuffs i.e. it provides the biggest net flow of food to global markets. Brazil is one of the few large producers with additional capacity to increase exports. Its model of agriculture is touted as a model for the development of Savannah agriculture in Africa. Brazil is also by the same token one of the countries, of near-continental size, where the future of the world’s climate will be decided. The Amazon is key to the global ecosystem. And land use changes more generally make Brazil, despite its modest level of industrial production and affluence, into one of the largest sources of CO2 emissions in the world.

You might be tempted to think that none of this is a surprise. From the 16th century Brazil was settled by Europeans and their slave-labour force as a commodity producing territory. From the 19th onwards, Brazil was famous for production of coffee. In 1850 it produced half of the world’s crop. Coffee was the main source of wealth in cities like Sao Paulo. But though this is true, as recently as the 1960s Brazil was a country that was still heavily reliant on global markets to feed itself. Large parts of the country suffered from hunger and not just on account of Brazil’s legendary inequality, but because Brazil’s agricultural system was so poorly developed. In the early 1960s it was not just tractors and fertilizers that were scarce on Brazilian farms, but basic implements such as plows.

The transformation of Brazilian agriculture in the half century since the 1970s has been spectacular. Food output has increased eightfold. The benefits have not been equally spread, but Brazil’s agricultural production has contributed to raising the standard of living of Brazilians themselves. Brazil today is famous as the world’s largest beef exporter, but 80 percent of Brazilian meat production is consumed at home. The relative price of food has fallen in Brazil for decades, sustaining the standard of living and supporting the redistributive measures of the Workers Party governments. For global markets, Brazil is a huge producer of wheat. Brazil rivals the US as an exporter of soy and is a favored supplier of China and its pig farms. With Saudi Arabia, President Lula conducts diplomacy over chickens.

As preparation for a recent trip to Brazil, to help launch Phenomenal World’s new Portuguese and Spanish-language editions, I plunged into Brazilian economic history and opened a bunch of tabs:

Amidst all this I found some truly interesting reading:

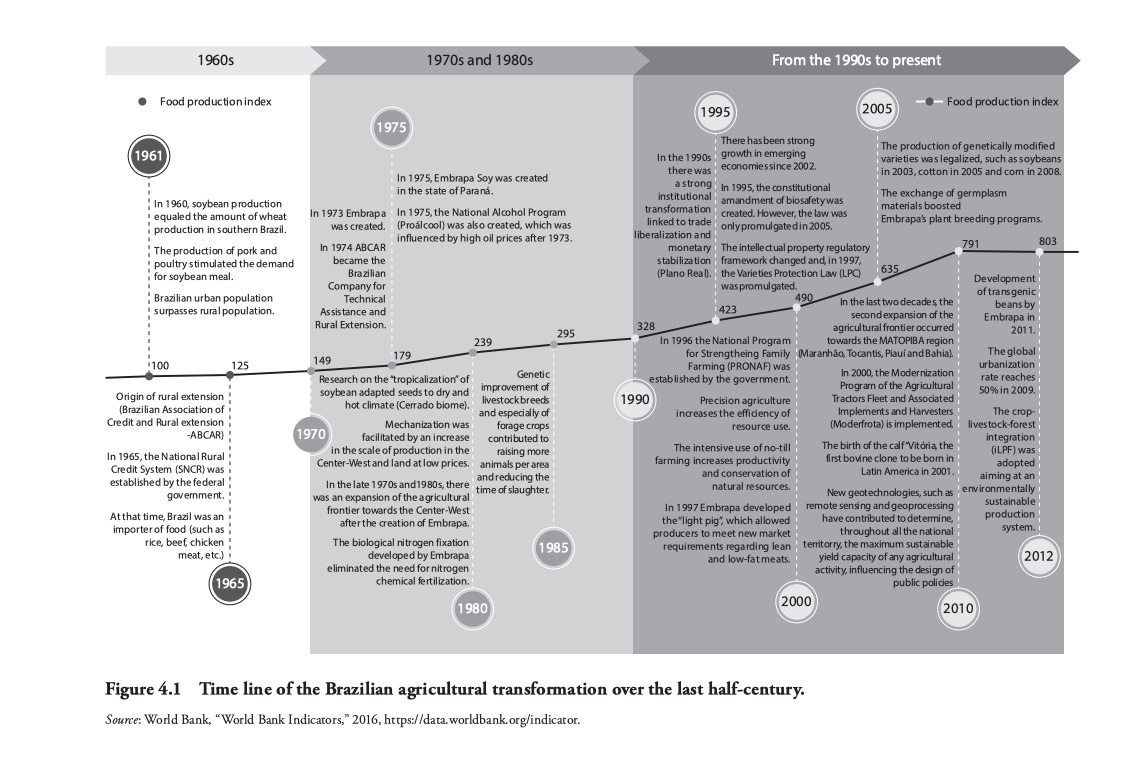

Up top, let me put this timeline from Albert Fishlow and José Eustáquio Ribeiro Vieira Filho Agriculture and Industry in Brazil. Innovation and Competitiveness (2020).

Five points leap out from the literature.

#1 Brazil's agricultural leap forward is celebrated as a product of modernization i.e. mechanization, research and human capital formation, not simply resource mobilization. If there is a hero of the story, it is Embrapa, Brazil’s premier agronomical research corporation. Apart from know-how, tractor mechanization assisted by rural credit systems propelled the growth surge. Brazil is now not only self-sufficient in farm machinery but an exporter from factories run by all of the major global producers worldwide.

Source: Herbert S. Klein, Francisco Vidal Luna, Brazilian Crops in the Global Market. The Emergence of Brazil as a World Agribusiness Exporter Since 1950 (2023)

#2 After decades of industry-focused development policies from the 1930s through the 1960s, it was the military regime, which took power in 1964 in a coup backed by the USA and Britain, that launched Brazil on this spectacular agrarian growth boom. Brazil today is quite taciturn about the legacies of that regime. There is little talk about coming to terms with the past. Lula prefers, in his words, “not to dwell on it”. But this was conservative modernization with a capital “c”. Working class wages were squeezed hard. Millions were displaced from poverty in the countryside to poverty in the cities.

#3 Brazil’s agriculture was like its industry through the 1980s very much supported by nation-state measures. The scale of transfers, notably in the form of subsidized credits was large. At the same time prices were held low, forcing a process of mechanization and labour shedding. Then, following the macroeconomic shocks of the 1980s and 1990s, and IMF-approved austerity regimes, government support was abruptly withdrawn. Both agricultural and industrial subsidies were squeezed hard, import protections were lifted. Overvaluation of the currency to curb inflation further hurt domestic production. But whereas industry wilted, agriculture survived. And then, in the early 2000s, China arrived as a huge customer, changing the balance in global commodity markets in favor of producers like Brazil.

#4 The impact on Brazil of the agrarian economic boom was positive in many ways. Above all it lifted the specter of balance of payments crises and the stop-start economic policies those imposed.

Source: Herbert S. Klein, Francisco Vidal Luna, Brazilian Crops in the Global Market. The Emergence of Brazil as a World Agribusiness Exporter Since 1950 (2023)

But the overall socio-political consequences are more ambiguous in that capital-intensive, globally orientated agriculture forms the heart of a new core of highly unequal and globalized wealth. The agrarian lobby has huge influence in Congress and its relationship to democracy is largely instrumental. Successive governments of the left sought to redress the balance with rural settlement programs. But in economic terms these have been far from a success. Rural poverty is entrenched at the same time as the countryside is largely depopulating. By implication the welfare policies of Brazil’s Workers Party governments have been driven by the need to manage the lurching rebalancing of poverty from the countryside to the cities. Brazil is still searching for a growth model that will incorporate the majority of the population into high-productivity and well remunerated employment. Not for nothing, neo-industrialism is the buzzword of the moment.

#5 Finally, Brazilian economists and economic historians are at pains to talk down what one might expect to see as the great trade-off, namely the impact of agricultural expansion on the environment. A key point of the literature is to stress that in its new and modern phase, Brazilian agriculture has overcome its historic dependence on extensive growth. As Klein and Luna write in Feeding the World Brazil's Transformation into a Modern Agricultural Economy (2018)

Finally we should note that what this book does not do is to try to study the social conflicts over land that have become the norm in the more traditional regions of the North and Northeast, or the major question of the dismantling of the Amazon. As we intend to demonstrate, this agricultural revolution has occurred and continues to evolve without the need for more land expansion or for the continued dismantling of the rainforest. The illegal mining and cutting of timber in the Amazon, though a major problem for Brazil and the world, is not fundamental to the modern commercial sector of the national economy.

In his punchy introduction to the Agricultural Development in Brazil. The Rise of a Global Agro-food Power (2019) a collection edited with Rodrigo Lanna and Zander Navarro Antônio Márcio Buainain argues that it is high-time to update the narrative about Brazilian agriculture to reflects its dramatic dynamism and global success.

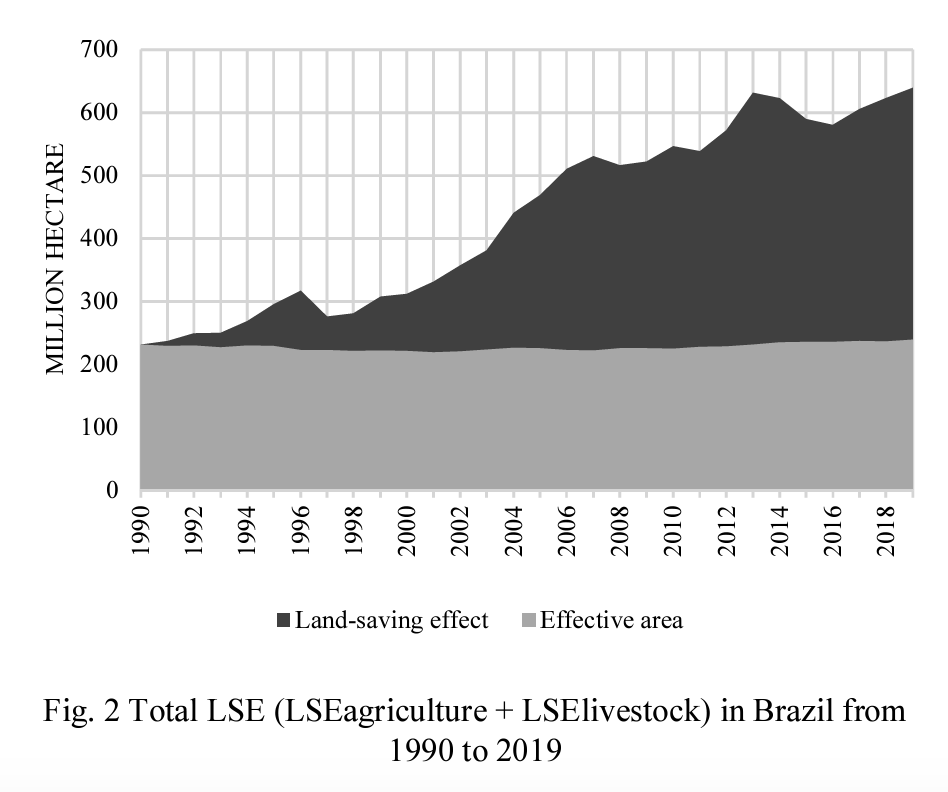

Not only have there been substantial efficiency gains in Brazilian farming, but a chorus of economists and economic historians goes farther. They contend that Brazil’s agricultural expansion has been “land-sparing”. In support of this jaw-dropping thesis, they invoke the following graph, which shows agricultural output surging without any increase in land use.

Source: Alcantara et al 2021

Any inherent relationship between Amazon deforestation and Brazil’s agricultural boom is denied by reference to the experience of the 2000s. As they point out, at the moment that Brazil’s agricultural output surged Lula’s governments was succeeding in suppressing illegal deforestation.

Source: Stabile et al 2020

For a few days I have to admit that I was stopped dead by these numbers, not knowing what to make of the gap between these highly competent economic assessments and the common story of Brazil’s economic data. And then I began to dig a bit deeper and have, I think, gone some way towards resolving the puzzle. (Those with more knowledge PLEASE chime in!).

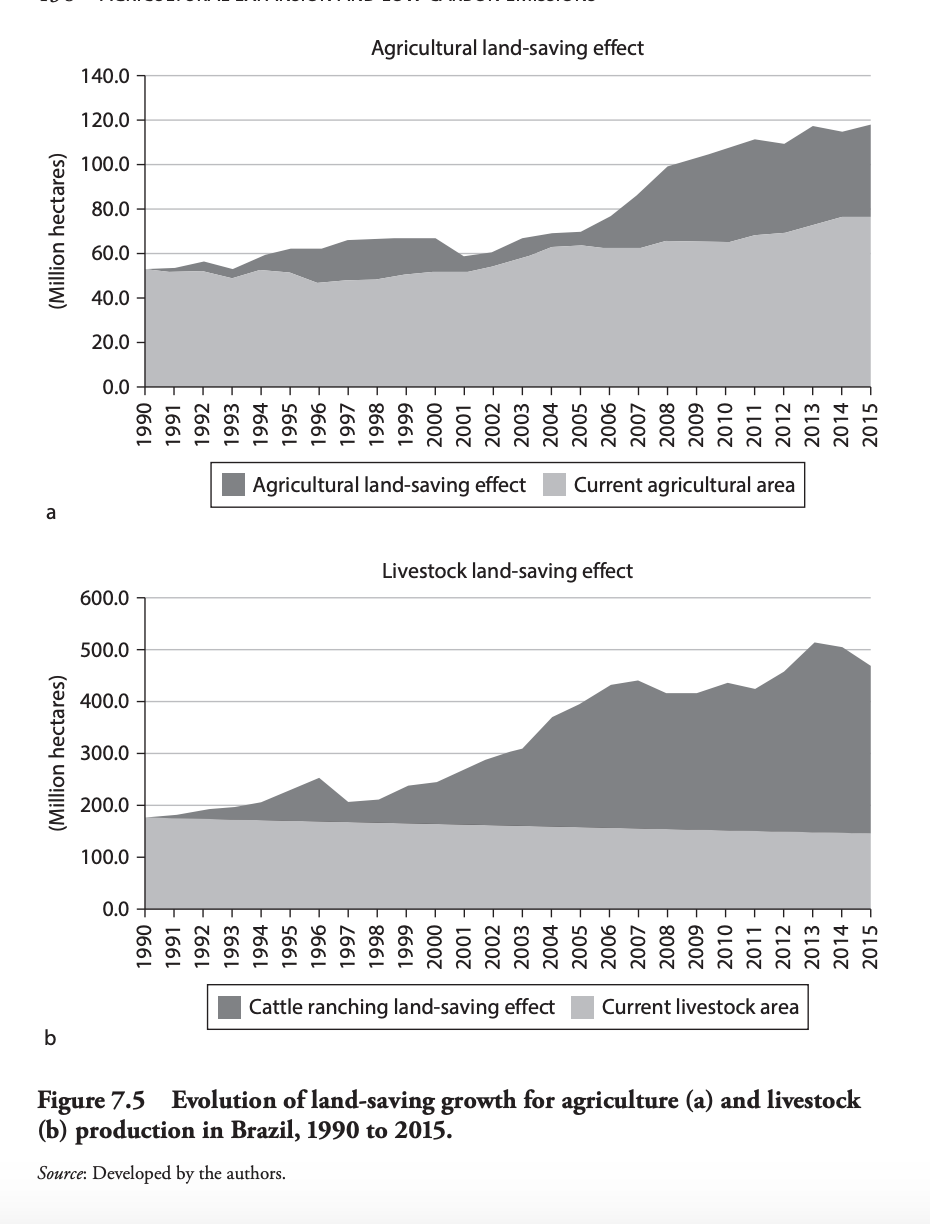

First and foremost, land-use in Brazil is split into two very unequal parts. The larger of the two is the low-intensity and highly extensive use of land for pasture. The second, far smaller, is the far more intense use of land for farming. The counter-intuitive finding that land use in Brazilian agriculture has not increased in the last quarter century results from lumping these two very different parts of the agricultural system together. For reasons that are not altogether obvious and are not confirmed by FAO surveys, Brazil’s official data for pasture land use show a secular decline over time. As the animal heard increase this results in a dramatic productivity trend and the counter-intuitive result that agricultural growth in Brazil has resulted in land-saving. Given the scale of the pasturage numbers they swamp all other trends in the data. If we break out farming and animal husbandry separately we see a picture that looks more familiar.

Source: Fishlow and Filho (2020).

There has indeed been some productivity increase in Brazilian farming, but the land sparing story applies with real force to animal husbandry, not to farming where land use has increased. Furthermore, lumping together the land use of all farming hides further important differences.

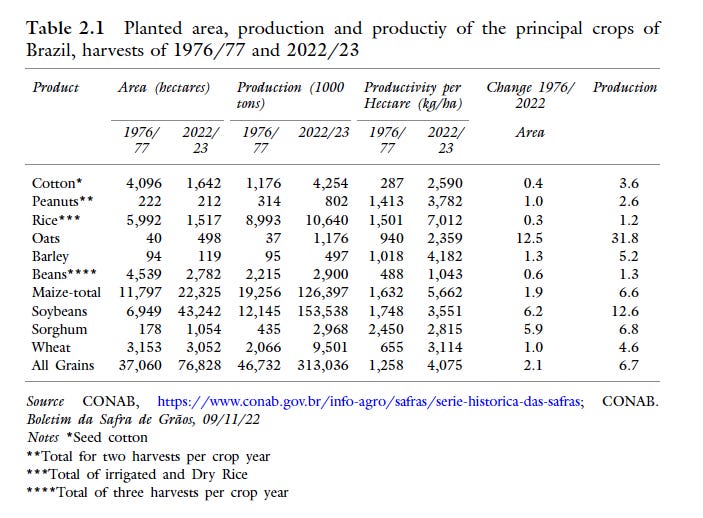

Two crops dominate production in quantitative terms - maize and soy, the new star of Brazilian agriculture. As far as productivity gains and land use are concerned, the balance in the two cases is quite different.

Klein and Luna 2023

Whereas the area devoted to maize barely doubled, productivity per ha increased by a factor of almost 3.5. By contrast, productivity per hectare in soy barely doubled and land use multiplied six times. This is “land-saving” only in the most relative sense.

The same conclusion is apparent if we look at the regional pattern of production across Brazil’s giant territory.

It is true that agricultural land use trends have been flat across much of Brazil. This is true for all regions except one, the Center-West, where the area under cultivation has trippled. This is the region critical for the agricultural boom, particularly in soy.

Crucially, this is not Amazonian but the famous Cerrado Savannah region. Making this fertile is a huge win for Brazilian agronomy. But though it is not as biodiverse as the Amazon and does not enjoy the global visibility, it is nonetheless vital for Brazil’s ecology. And the damage it has sustained in the course of the boom is dramatic.

Source: Agroicone

Furthermore, some authors suggest that there is spillover from the Cerrado boom to the Amazon, with cattle farmers displaced from the Cerrado to the Amazon region.

So here are the essential points:

Amazon deforestation is terrible and major producers do engage in it and are tied to global supply chains. But the main offender here is beef and in quantitative terms Amazonian deforestation is a spillover and not a central dynamic in Brazil’s agricultural boom of recent decades. It follows that to save the Amazon we don’t need to halt the Brazilian agroindustrial juggernaut. What needs to be done is for Brazilian authorities to vigorously and proactively enforce its extensive forestry laws and protect indigenous rights. This is no mean task. It involves confronting substantial local interests with the greater force of national power. But it does not involve a revolutionary overthrow of the existing order of things.

This does not mean however that the Brazilian boom is a pure productivity story that has no relationship to increasing land-use as is suggested by the “land-sparing” slogan. The land-use expansion without which Brazil’s agricultural boom, as we know it, could not have taken place, came in the Cerrado. There it has done significant and irreversible ecological damage.

In the Cerrado the trade-offs are real. It is not a matter simply of enforcing the laws, but of setting political priorities. A good future scenario consists in further intensifying the pursuit of productivity and forcing intelligent land-use in the Cerrado, such that further expansion takes place within degraded pasture land.

Overall the big trade-off in Brazilian agriculture that matters in the foreseeable future is not a stark choice between wilderness and the global food supply. This is a false choice. There is huge slack in Brazil’s still very baggy agricultural system. Crucially, there is huge room to improve the efficiency of cattle-ranching so as to reallocate the vast territory given over to low-intensity pasturage to more productive agriculture. This rebalancing is what is hidden in the seductive but misleading data promising a future of “land-saving” agricultural development. The aim of policy should be to make that more than a figment of the statistical imagination.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Excellent piece! Three brief comments: on the cattle-agriculture nexus, on cerrado v. Amazon, and a timelapse video of agriculture expansion.

1. Cattle-ranching and grains are hard to separate that neatly, in practice. The most common pattern of land use in Brazil, underpinned by flimsy land titles, is the following cycle: non-sustainable forestry (cutting down trees), slash-and-burn for pastures, cattle grazing, agriculture. Early stages bear the deforestation brunt and sell on ‘legal’ land titles for agricultural use, as prices (for deforested and ‘legally owned’ land) rise in a financialised process. This article explains it well (see esp. section 4): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104313.

2. The expansion of soybeans and maize has indeed been concentrated in the cerrado/savannah but already involves the Amazon. The northern section of the centre-west region is the Amazon biome.

3. This time-lapse video is centred on Sinop, in the north of the state of Mato Grosso (the fastest growing state in Brazil for the last decades, focussed on soybeans and maize and involving cerrado and Amazon). The steady transition from forest to soybeans is striking: https://earth.google.com/web/search/sinpo/@-11.2357524,-56.31880299,485.02016521a,724082.66978793d,35y,0h,0t,0r/data=CjoiJgokCQAAAAAAAAAAEQAAAAAAAAAAGQAAAAAAAAAAIQAAAAAAAAAAOhAIAREAAAAAAAAAQBjLDyABMikKJwolCiExU2JtTTRWMXhiM3A4Y2FQdUpEQk9nTXBobDZNeXFlTGsgAToDCgEx

Many thanks for this. Food fo thought if you can forgive the pun.

The following piece is deeply pessimistic about climate change and the diminishing capacity of the rain forests to sequester carbon. The cause? Not deforestation, which is declining, but climate change itself. Thanks again

https://theconversation.com/we-tracked-300-000-trees-only-to-find-that-rainforests-are-losing-their-power-to-help-humanity-133122