Chartbook 271 Reasons of State: Memory politics, U-Boats, Iran & the German-Israeli relationship

A lot has been written about the shambles that the Gaza crisis has made of German memory culture and public life.

Barely a day goes by without news from Germany of some further act of censorship, silencing, deplatforming, directed at artists and public intellectuals seeking to understand and react adequately to the awful violence in Gaza. Voices that once celebrated German memory culture as a model for other democracies, now declare that it has gone badly off the rails.

Of course, the difficulty in responding adequately to the horrible situation is not confined to Germany. And in Germany, dogmatism around anti-anti-semitism did not start with October 7 2023. But it has escalated spectacularly since October. In few if any other places are voices critical of Israel censored so fiercely and the accusation of anti-semitism used so frequently or with such bludgeoning effect.

What is going on? Regardless of your position on Gaza, Germany’s reaction at this point calls for an explanation.

The first and most commonly cited factor at work is the Holocaust and Germany’s historic burden of guilt. But focusing on the memory politics of the Holocaust ignores a mesh of other considerations both inside and outside Germany. To see many of these factors exposed you have only to do something obvious: Go back to Angela Merkel’s speech to the Knesset on March 18 2008, which defined the new era of German-Israeli relations and read it carefully. Not enough folks interested in making sense of the current moment have done so, and I include my own earlier commentary in that criticism.

For the original German see the official website. There is an official English translation, here.

The speech is important to the current moment, because in it Merkel declared that Israel’s security was a key part of Germany’s Staatsräson or raison d’état. That is the phase that was taken up by the current German governing coalition in 2021 and has been echoed insistently by Chancellor Scholz, Robert Habeck and other spokespeople of the coalition, ever since.

As was pointed out by Hans Kundnani in a recent essay in Dissent, Merkel’s positioning was markedly different than the interpretation placed on the Holocaust by Joschka Fischer when he served as Foreign Minister in the first Red-Green coalition in the 1990s. As Kundnani describes Fischer’s evolution:

In 1985, on the fortieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe, Fischer wrote an article for the weekly newspaper Die Zeit that concluded: “Only German responsibility for Auschwitz can be the essence of West German Staatsräson. Everything else comes afterwards.” … At the time, he believed that this principle meant rejecting the use of military force. But he abandoned that position after the Srebrenica massacre in 1995. … Fischer came to support the idea of military intervention to prevent genocide. Until then only the center-right had advocated this position; the Greens saw it as a pretext for German remilitarization. But if his generation did not use all means to prevent genocide, Fischer asked in an open letter to his party, would they not have failed in the same way their parents had during the Nazi era? Three years later, when Fischer became foreign minister … (t)he issue of the implications of Auschwitz for German foreign policy came to a head almost immediately with the question of military intervention to prevent ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. The debate was especially intense among Greens, who were committed both to the idea of peace and to responsibility for the Holocaust. They seemed to face a choice between two principles: “Never again war,” which led some to oppose the NATO military intervention in Serbia, or at least German participation in it, or “Never again Auschwitz,” which led others (like Fischer) to support the intervention and German participation.

Merkel in 2008 drew no such far-reaching conclusions. For her Auschwitz implied first and foremost a particular German responsibility for Israel. What precipitated that shrinking of horizons, from universalism to particularism, a shrinking that continues to define the horizon of mainstream politics in Germany today?

The main difference is surely the issue of Israel’s security.

The unspoken assumption that informed Fischer’s universalization of the Holocaust as an example of genocide, was the assumption that Israel’s security was no longer seriously under threat. To conclude that the main lesson of the Holocaust was universal you needed to presume that the Middle East was on the path to peace, which made sense in an era in which Germany and Europe were firmly committed to a “peace process” organized around the two-state solution. Of course, German-Jewish history retained its awesome and specific weight. Indeed, it was more present than ever in the unified Germany in the monuments and museums erected in Berlin. But those anchored a newly thriving Jewish life in the German capital that pointed to a wider global future.

We now know that this 1990s version of globalization was to prove short-lived. The world of the 2000s was much more dangerous. Not that the Arab states were mobilized against Israel as they were in the 1960s and 1970s. There would be no repeat of 1973. But in the early 2000s Israel faced the fury of the Second Intifada. As Rudolf Dreßler Germany’s ambassador at the time pointed out, in a 2005 essay that launched the association between reason of state and Israel’s security, scaled to the population of Germany, Israel suffered 12000 dead and almost 70,000 casualties. On the Palestinian side the casualties were more than three times that number.

After 2003, America’s Global War on Terror destabilized the entire region. The election breakthrough by Hamas in January 2006 and it seizure of power in Gaza, initiated a new phase of confrontation. In the summer of 2006 Hizbollah attacks provoked Israel into an ill-fated counter-attack into Lebanon. The principal backer of both Hamas and Hizbollah was Iran, where in June 2005 Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected as President, openly espousing gutter anti-semitism, Holocaust denial and calling for the destruction of Israel. Silently under Sharon and Olmert and then loudly under Netanyahu from the spring of 2009, Iran, not Palestine, moved to the center of Israel’s security preoccupations.

If you read Merkel’s 2008 speech to the Knesset against this context it is quite clear that the principal threat she has in mind to Israel’s security was not Palestinian national claims, but Iran. The famous “Staatsräson” passage is directly linked to Iran.

One thing must be clear here – I said this before the United Nations last September and I want to repeat it here today: The world does not have to prove to Iran that Iran is building a nuclear bomb. Iran has to convince the world that it is not striving towards such a bomb. Here of all places I want to explicitly stress that every German Government and every German Chancellor before me has shouldered Germany's special historical responsibility for Israel's security. This historical responsibility is part of my country's raison d'état. For me as German Chancellor, therefore, Israel's security will never be open to negotiation. And that being the case, we must do more than pay lip-service to this commitment at this critical point. Together with its partners, Germany is setting its sights on a diplomatic solution. But if Iran does not come around, the German government will remain fully committed to sanctions.

Iran was challenging everyday life in Israel through its proxies in Gaza and Lebanon. And though Merkel does not say so explicitly, the ultimate threat posed by Iran’s nuclear program was that it would put in doubt Israel’s regional monopoly of nuclear weapons. This is where Staatsräson takes on a shadowy but undeniably material reality.

When German politicians talk about Staatsräson and Israel’s security they are caught in a trap which prevents them from saying the important thing out loud.

It is easy to mock Germany’s security commitment to Israel - I have been guilty of doing so myself. At the moment many analysts point to Germany’s running military exports to Israel. They are second only to the USA. But what do these consist of? Only a small fraction are weapons or ammunition. Most are less significant components - trucks, bullet-proof glass etc. Germany has helped Israel out by returning drones that it had formerly leased from Israel.

But such lists are misleading. Germany’s security commitment to Israel appears so nugatory, because German politicians are not free to say out loud what really matters. The really important weapons deliveries that Germany has made to Israel in recent decades are big and lumpy, they take years to design and deliver and cost billions of euros: they are submarines. Since the 1990s, German dockyards have been the prime contractors for Israel’s submarine fleet.

What, you might ask, have submarines got to do with the conflict in the streets of Gaza or on the border with Lebanon? Not much. But those submarines are key to Israel’s regional security. Sophisticated modern U-Boats, supplied by German dockyards, in large part paid for by the German tax payer, hiding in the depths of the Mediterranean, or off the Persian Gulf provide Israel with what its military planners most crave, “strategic depth”. And what everyone knows but will not say out loud is that each of Israel’s vessels is equipped with a complement of nuclear-tipped cruise missiles whose warheads have a destructive force of perhaps 200 kilotons, or 14 times that of the Hiroshima bomb.

Germany-supplied submarines complete Israel’s nuclear triad - the other two poles being air-dropped bombs and Jericho missiles. The submarine-based warheads are likely smaller, the cruise missiles have more limited range and accuracy, but they provide Israel with the gold standard in nuclear deterrence, a credible second-strike capability. If Iran imagined that it might be able to knock out Israel’s arsenal of land-based and air-based nuclear warheads in a preemptive strike, it would have to face an onslaught of atomic hellfire launched from Israel’s submarines. All told, Israel is thought to have perhaps 90 nuclear warheads and it has test fired the Popeye turbo cruise missiles that carry them at least once, with American collaboration in the Indian Ocean.

Those submarines, designed, built and paid for in cooperation with Germany are Israel’s true security guarantee. They are what German politicians, at least those in the know, are gesturing towards when they say Israel’s security is German reason of state. Insofar as Germany has a “deep state” here it is - offshore, deniable collaboration in the development and building of Israel’s nuclear deterrent.

If we believe reports from Die Welt, Germany’s collaboration with Israel in securing its nuclear deterrent may go back to the early 1960s when credible sources suggest that after talks between Ben-Gurion and Konrad Adenauer, Germany agreed to help Israel pay for its nuclear program. Conservative politicians like Franz Joseph Strauss, who would have dearly liked for Germany to have its own atomic arsenal, dropped heavy hints about this cooperation. Israeli sources have done the same. There are line items in the balance sheets of the KfW that a ten-year credit of $500 million was provided on preferential terms for “industrial and infrastructure development in the Negev”, where the Dimona nuclear complex is located.

By the 1970s Israel was looking to develop a new fleet of submarines and turned to German designers. In the 1980s talks continued about Israel U-boat orders. At a time of acute financial stress, submarine projects were controversial within the Israeli military establishment, with senior military figures preferring conventional weapons. In 1987, under heavy pressure from the US, the Israelis took the fateful decision to cancel the Lavi, their own fighter-jet project and to rely, instead, on US F-16s. In 1990 it seemed that the Israel’s submarine ambitions might go the same way. But then came the Kuwait war and the revelation that German engineers had helped to build the arsenal of Iraqi Scud missiles of which 39 were fired against Israel. In deep embarrassment, Helmut Kohl’s government agreed to pay for 2 modern diesel-electric U-Boats to be delivered to Israel at German expense, with Israel splitting the cost of a third. Having at least three submarines in its fleet allows Israel to maintain a continuous rotation of boats at sea. A veil of silence was drawn over what Israel intended to arm the submarines with, but it could be assumed that Israel would not be answering the next missile salvo with torpedos.

In 2005 the government of Gerhard Schroeder as one of its last acts agreed in principle to the delivery of a new generation of submarines with even more sophisticated technology. Newly elected, Angela Merkel, was consulted by an Israeli delegation, and swiftly gave her approval. It was clearly a violation of Germany’s strict armaments exports regulations, but if Kohl and Schroeder had agreed, she was only too happy to fall into line.

It was not a hard choice. Unlike most young East Germans Merkel grew up in a household suffused with concern for Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms with the past). Her father settled as a priest in the GDR in search for an answer to Germany’s Nazi past. Despite her fluent Russian, her orientation from the start of her career was markedly pro-Western and American. In the early 2000s in the aftermath of the Kohl-era in the CDU, Merkel was notable for a her neoconservative, pro-American positioning both on economics and in foreign policy. Merkel loudly declared her support for the Bush administration’s disastrous campaign in the Middle East. In 2005 as leader of the opposition she first picked up the concept of reason of state to emphasize that “Germany’s responsibility for European unification, for the trans-Atlantic partnership, and for the existence of Israel - this all belongs to the core of the reason of state of our country and to the basic purpose of our party.”

As Chancellor, Merkel made relations with Israel into Chefsache (an issue for the boss) limiting the role of the Foreign Ministry. She shifted Germany’s positioning from a focus on the peace process and the two-state solution to defending Israel’s security. She was the first leader of the CDU to insist that her party commit itself to Israel as a Jewish state, and thus against the Palestinian right of return. She repeated Israel’s line on Hamas in 2006 verbatim, demanding recognition of Israel’s right to exist. She blamed Hamas exclusively for the escalation of violence that led to the 2008/9 Gaza war. Her 2008 visit was intended to initiate a regular series of intergovernmental consultations.

Aside from the comment on Staatsräson, Merkel’s Knesset speech is notable for the way she situates the situation of Israel in the Middle East against a broader diagnosis of globalization and its challenges for democracies. Again, this marks a subtle shift from Joschka Fischer’s value based universalism. Faced with the dangers of state failure and ethnic conflict on Europe’s boundaries and beyond, Fischer argued that Germany had a special responsibility to respond to the threat of genocide. Faced with an uncertain and dangerous world, Merkel, argued, as she had done in 2005, that Germany had a special responsibility to stand with its friends - its European partners, the United States and Israel. It was a vision of the world organized around alliances based on claimed values. Israel as “the democracy in the Middle East” was a natural ally for Europe in a dangerous region.

In the wake of 9/11 and the disaster of GWOT, how to rebuild a new values-based multilateralism was the question of the day. A few weeks after her Knesset speech, at the infamous NATO summit in Bucharest in April 2008 Merkel would find herself fighting to restrain the Bush administration from extending membership promises to Ukraine and Georgia. For Merkel, Israel was clearly a far more natural fit for a security commitment. Not only was there the Holocaust, but rather jarringly in her appearance in the Knesset Merkel also celebrated Israel’s triumphant tech economy. Surely, Israel with its highly sophisticated economy would see great advantage in closer association with the giant European market, over whose future Merkel was, at the time laboring to fashion the so-called Lisbon compromise. The essential elements of that deal, completed in December 2007, was to abandon tighter European confederation in favor of nation-to-nation deals and a stronger global focus. A close association with bustling high-tech Israel suited Merkel’s vision of a global future rather better, it seems, than tight links to post-Soviet Georgia or European laggards like Greece.

Merkel now tends to be seen as a cynical advocate of appeasement - notably with regard to Russia and China - but Israel brought out a clear statement of the centrality of values to her vision of the world. And this fed directly back into invocation of Staatsräson. What both Merkel’s speech-writers and the German ambassador wanted to signal with this somewhat anachronistic sounding phrase was a commitment that went beyond the whims of political opinion, that was abiding and rooted in the most fundamental commitments of the German state.

As Cameron Abadi of Foreign Policy and I harped on in our live podcast from Berlin last autumn, the idea of reason of state harks back to a pre-democratic, age of statecraft. With good reason German constitutional jurisprudence has generally fought shy of such logics. But what Merkel was saying before the Knesset in 2008 was precisely this: the Federal Republic’s commitment to Israel doe not depend on fickle democratic mandates or public opinion on the German side. It is a deeper principle, if necessary to be defended, argued for and insisted upon in the face of an unwilling German public. Indeed, in front of the Knesset, Merkel explicitly defined the task of German democratic leadership as cleaving to Israel even in the face of public opinion polls that revealed a groundswell of German attitudes that were far more skeptical about Israel and Germany’s historical obligation.

This notion of democratic leadership against the grain, is also not one we associate with Merkel. But Israel brought out in her a stronger and most explicit vision of leadership. At the time that Merkel spoke, almost half of Germans, according to polling done for the Stern magazine by Forsa thought of Israel as an aggressor state. Only 30 percent believed that it respected human rights. Only 35 percent of Germans shared the view so forcefully argued by Merkel that Germany had a special responsibility to Israel. 60 percent denied that Germany had any special responsibility. Repeated regularly over subsequent years, the Forsa surveys have consistently confirmed these numbers. Then as now, the contention by Germany’s political elite that their country owes a special responsibility to Israel’s security, flies in the face of the preferences of the German public.

Nor did Merkel in front of the Knesset, flinch from acknowledging one of the principal reasons why it was important to reemphasize this German responsibility. German unification in 1990 had brought about spectacular change. As she said before the Knesset, she spent her first 35 years in a state, the GDR, that treated the Holocaust as the responsibility of the other German state, West Germany. As the Forsa surveys showed this had left its trace. In 2009, fully 68 percent of East Germans denied any special responsibility for Israel and 28 percent of supporters of the Left party, particularly strong in the East, questioned Israel’s right to exist.

The crucial point to make is that much as it seeks broad influence, Germany’s memory culture is in its standard form - Vergangenheitsbewältigung as a project - is a project of Germany’s educated elite, its self-appointed thought-leaders. In this sense the anachronistic resonances of “reason of state” were not misplaced. The commitment of Germany to Israel’s security, come what may, was a counter-majoritarian project, backed up by a commitment to policing and managing, not to say censoring, domestic German public opinion. This is an understanding shared on the cultural left, in Germany’s public intellectual and cultural scene. But it is is also true for the conservative culture warriors who head the upper echelons of the right-wing Axel Springer Verlag and the editorial cliques that run the Bild Zeitung, Germany’s biggest tabloid newspaper. When the militant head of Axel Springer, Mathias Döpfner, declares "Und natürlich: Zionismus über alles. Israel my country” - with the latter phrase expressed in English - he knows he is not speaking for a majority of Germans. When the left-wing cultural scene celebrates the revival of modern Jewish culture in Berlin, and places it alongside diasporic Arab, Turkish and Persian culture in a generous and diverse mixture, they know they carry only a minority of enthusiasts along with them.

As was clear throughout the 2000s, the native German public, notably in the East harbored xenophobic views including anti-Black racism, anti-Asianism, anti-semitic attitudes and most extensively Islamophobic views. At the same time, both anti-Zionist and anti-semitic attitudes are common in the Muslim minority population. Since 9/11 breaking the Islamist networks operating in Germany has been an ongoing battle for police and security authorities. But more generally since the 1990s Germany has been struggling for categories, legal frameworks, policies and political languages to accommodate the huge transformation that migration has brought about.

The Red-Green coalition (1998-2005) had pushed a more expansive attitude to Germany’s large migrant population. Merkel was no multi-cultural enthusiasts, but she did not depart from the new consensus that accepted diversity as a fact about modern German life. That this could reopen old faultlines and stir new prejudices was clear. In 2008 on the anniversary of Kristallnacht the Bundestag launched the first of a series of enquiries into anti-semitism in Germany, which, when it reported in 2012 came to the disturbing conclusion that at least 20 percent of the population in Germany expressed at least latent anti-semitic attitudes, placing Germany in the midfield of the European ranking of anti-Jewish prejudice.

In short, when Germany’s head of government became the first to speak to the Knesset and made her commitment, the identification of the German political class with Israel’s security was already complex and braided from many strands, both foreign and domestic. It was formulated explicitly, as Merkel did, not just against the history of the Holocaust but against a broader diagnosis of a complex, unstable and at times dangerous world in which Germany’s political leadership committed itself to a project of strategic support for Israel and domestic self-policing and regulation.

***

Despite this emphatic commitment from Merkel’s side, the fifteen years between Merkel’s Knesset speech and October 7 2023 were not easy for German-Israeli relations. The stressors were numerous:

Though Merkel signaled a meaningful shift to a primary commitment to Israel’s security, rather than to the peace process as such, this depended on retaining a commitment to the two-state solution as a long-term vision. This tacit assumption would be put under severe strain by the political dominance of Netanyahu, beginning with his second stint as Prime Minister in March 2009. In a way that Germany could not ignore, his governments openly subverted the two state solution both through aggression towards Gaza and settlements in the West Bank on a huge scale.

Meanwhile, Germany continued its commitment to supporting the Palestinian authority and to relief aid in Gaza - both bilaterally and by way of the EU. Germany, was one of the largest donors to both UNRWA in Gaza and the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank. Germany sees this as part of its historic commitment to regional security. It is not lost on Germans active in the region that the Palestinians have paid a high price for Germany’s crime. This earns Germany’s criticism from Israeli hawks who see it more or less directly funding Hamas.

At the UN, as the majority of the General Assembly pushed to upgrade Palestine’s status, Germany acted as a consistently retarding force. It also shielded Israel against critical positions that might otherwise have been adopted by the EU.

Further tension was added by the fact that Netanyahu’s cohort of Israeli politicians and propagandists routinely invoked the memory of the Holocaust as a source of leverage, not just in public but even in personal clashes with Merkel and her team.

Israeli propagandists vigorously evoked the threat of anti-semitism to the diaspora, validating Israel as the ultimate source of security for all Jewish people wherever they are in the world. Germany did not deny the reality of anti-semitism both worldwide and in Germany. But the relentless emphasis on the anti-semitic menace challenged Berlin’s efforts to present Germany a welcoming and attractive place for Jews, whether Israeli or not.

The collapse of Arab state power in the 2011 crisis relieved pressure on Israel. Never had it faced less serious threat from Arab militaries. But it entangled Europe in the region in new and highly dysfunctional way. To its credit Germany distanced itself from the misguided European-American intervention in Libya, but the ensuing chaos spilled over to Europe in the form of the refugee crisis. This reached its crescendo in 2015/2016, which led to an influx of mainly Muslim refugees and propelled the right-wing AfD and questions of racism and anti-racism to the forefront of German politics.

Meanwhile, Germany as part of the EU pursued tortuous nuclear negotiations and rapprochement with Iran, which yielded the 2015 agreement, vociferously opposed by Israel. Only for that painstaking agreement to be unilaterally renounced in 2018 by the Trump administration, which went over, instead, to a massive campaign of sanctions. Iran, unsurprisingly, reactivated its nuclear program.

In light of these powerful cross-cutting forces, 2008-2023 was a difficult time for German-Israeli diplomacy. The close government-to-government ties that Merkel hoped to launch in 2008 were put on ice. Conversations between the Israeli and German sides regularly degenerated into shouting matches. Merkel assigned Netanyahu to the same category as Putin - a statesman she simply no longer trusted. Nor was it an association that Netanyahu even sought to challenge. He boasted of his association both with Trump and Putin.

One way for Berlin’s diplomacy to square these circles was to combine active diplomacy to halt Iran’s putative nuclear program - which earned nothing but scorn from the Netanyahu-aligned press - with continued German commitment to Israel’s actual nuclear dominance.

One of the many issues on which Netanyahu disagreed with Israel’s military hierarchy was in his support for the submarine-based deterrent. At first, Merkel’s government sought to exploit this desire by tying deliveries of more sophisticated submarines to a slowdown in settlement activity. It didn’t work. Israel stonewalled, and Germany delivered the U-Boats anyway, bringing the fleet to a strength of six vessels, enough to maintain two at sea at any one time.

In October 2016 after a considerable internal struggle, the Israeli cabinet agreed to buy three more submarines for delivery in the late 2020s and early 2030s. For the German exporters, the decision resulted n an order of three new boats of the so-called Dakar class, for the price of 1.8 billion Euro of which by 2027 Germany will cover 570 million. This latest generation of submarines are the largest and most high-tech that the German docks have ever built. They boat’s sophisticated propulsion systems allow long phases of stealth underwater operation - a good second-best alternative to nuclear propulsion - and may also include vertical launch tubes for heavier nuclear-armed missiles. They are being built in sections at the TKMS-dockyards in Kiel and Emden. Since the original deal was signed, overruns and upgrades have raised the value of the deal to 3 billion Euros. So rich was the contract and so controversial, that it has led to many years of corruption allegations and investigations into the affairs of several of Netanyahu’s entourage.

Meanwhile, in Germany, the elite policing of criticism of Israel and of popular currents of anti-semitism, which was always a concomitant of Israeli-German-raison d’état, has become ever more frantic. Following the 2015/6 refugee crisis and Merkel’s expansive response, the politics of the Jewish, Israeli and Arab and Islamic minorities in Germany and the associated questions of anti-semitism and Islamophobia, and their counterparts in anti-racism and anti-anti-semitism have taken on an ever greater importance.

This plays out in the street, in daily personal encounters in German cities. It plays out in the highly visible police presence around every Jewish facility in Germany and in the harassment meted out to other minorities. It plays out in Germany’s underfunded schools where young people with migrant backgrounds in Germany often struggle thrive. And it plays out in the workplace where life chances are highly unequally distributed, notably for Muslim women who wear head scarves. The struggle plays out also in the polling and social investigations that seek to describe “public opinion” and in the discourse of politicians and the media that revolve around those results. And it plays out with particular drama in Germany’s large sector of publicly-funded culture.

By European standards, German public investment in culture is no more generous than its public investment in anything else, be it railways or internet-infrastructure. But Germany has big cities where spending is above average, notably Berlin. And it is the largest country in Europe with the biggest economy, so overall public spending on culture in Germany is impressive - roughly 14. 5 billion euros in total. That pays for a lot of exhibitions, conferences, prizes, performances, seminars and fellowships. On the whole, this helps to make Germany a very civilized place to live. In this forcefield the increasing diversity of Germany and the complexity of world affairs is celebrated and mobilized and politicized in dramatic ways. That is one of its jobs. But under stress it also creates an arena for the politicization of culture that is second to none. And from the late 2010s onwards it began to be moved very powerfully by the escalating situation in the Middle East and the dynamic of migration to Europe.

The hardline position of the Netanyahu administration mobilized global opinion, both voices on the Israeli left, on the Palestinianian side but also voices from the “global south” to which Germany’s cultural scene is at pains to give at least a selective hearing. At the same time, fears about rising anti-semitism in Germany, both from the “old German” right and the “new antisemitism” of migrant groups are easily mobilized in defense of Israel - “Israel my country” as Springer’s top man put it. The resulting tensions exploded into the open in a series of anti-semitic incidents in 2018, a Bundestag motion to ban any public funding from going to organizations that associated themselves in any way with Boycott Disinvestment and Sanction movement and in April 2020 the deplatforming of the prominent postcolonial theorist Achille Mbembe.

All of these are a long way from the realities of Middle East power politics, the precarious life of Gaza or even the street politics of Berlin neighborhoods like Neukölln. But they represent efforts by mainstream elites in Germany to hold the line that Merkel articulated so clearly in 2008. A rock-ribbed strategic, political and

"value-based” commitment to Israel, defined as essential to the historic project of postwar Germany, is defended by silencing anti-Zionist and Israel-critical discourse. It is at one and the same time both raison d’être and raison d’état.

***

The change of government in Berlin in 2021 changed nothing about this basic constellation. Despite the obvious impasse in the Middle East, the three parties that make up the new coalition - Greens, SPD and Liberal FDP - committed themselves in their coalition agreement to Israel’s security as Staatsräson. They did this in part to stifle possible criticism aimed at the Green Party, or from within the Green Party’s ranks. Annalena Baerbock the party’s candidate for Chancellor who became Foreign Minister had previously criticized the delivery of what she called “atomic submarines” to Israel. During the election she walked back those comments and the coalition agreement ends any further argument.

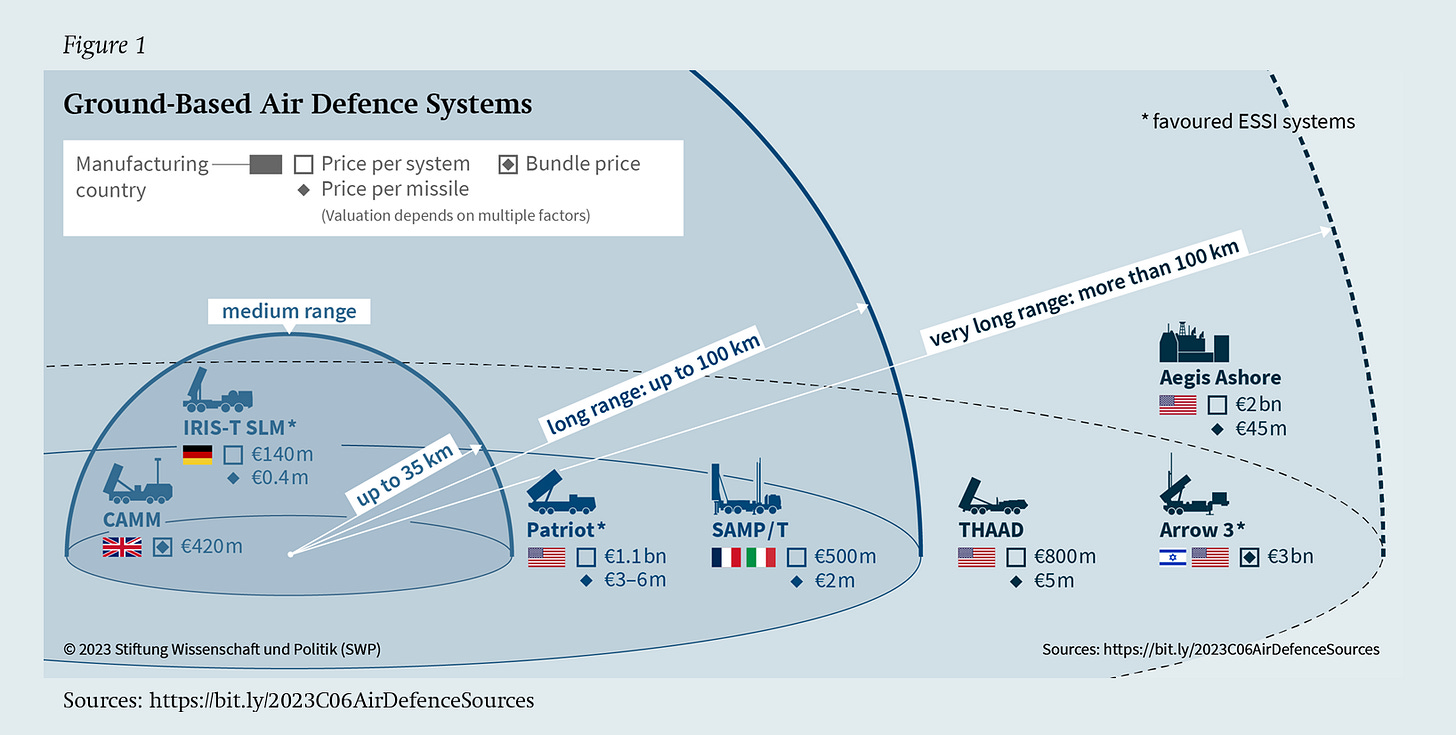

Following Putin’s attack on Ukraine and the Zeitenwende in German defense policy in 2022, that reason of state has taken another dramatic turn. In the spring of 2023 Chancellor Scholz made concerned noises about Israeli democracy and Netanyahu’s judicial reforms, but in August 2023 came the announcement of a historic new arms deal. This time, however, it would not be Israel buying German weapons, but Israeli weapons that would be procured by the Bundeswehr, as part of its Zeitenwende mobilization. With American approval, Germany announced that it would be buying the Arrow 3 high altitude missile defense system from Israel to the tune of at least 3 billion Euros, Israel’s largest ever foreign arms deal. Arrow 3 would form a key part of the Sky Shield joint missile defense system that Germany launched as a common European project in October 2022, much to the discomfort of France.

When Netanyahu’s Defense Minister Gallant visited Berlin in September 2023, just days before the Hamas attacks, the script of the meeting offered a perfect summary of the German-Israeli strategic relations since 2008. As summarized by the Times of Israel, Gallant remarked:

“Today, more than ever, we share common threats. The Iranian fingerprint is everywhere,” Gallant said, referring both to Iranian proxies on Israel’s borders and Iranian drone sales to Russia, pounding the battlefield in Ukraine. “In the face of Iranian aggression, we must prioritize security readiness and capabilities, as well as bold actions by the international community,” Gallant said. … Israel and Germany say that the Arrow 3 sale represents close and growing defense cooperation, … “Right now, we would only sell this system to Germany and the United States, because we are speaking about a strategic system. It would be delivered only to countries meeting certain standards, with respect to Israeli interests,” Gallant said. … “It’s an emotional moment, to be here as the son and grandson of Holocaust survivors, on German soil, in Berlin, to sign a defensive arms contract,” Gallant said. “It’s very important, personally and diplomatically. This moment of history leans on our past and dictates our shared future.” He called the sale “a moving event for every Jew. Before departing back to Israel on Friday, the minister is scheduled to visit the Platform 17 Holocaust Memorial to pay his respects.

Weeks later, amidst the immediate aftermath of the October 7th attacks and Israel’s massive response, the Bundestag budget committee gave its final approval to the Arrow 3 deal. Israel and Germany will thus be bonded together as part of a hyper-complex defense system of giant scale.

This then is the iron box that defines German-Israeli relations in the last 15 years. Historical memory informs a choice for Israel over a position of balance in the Middle East. Germany’s own security is put symbolically at stake in an ally with similar values. Iran, not Palestine, is the principal strategic concern. The concomitant of this raison d’état on the German side is anti-anti-semitism, as part of an elite project of domestic societal regulation which requires constant precarious balancing between liberality and control. In security terms, Germany and Israel share an interest in containing radical Islam, whether of the Sunni or Shia variety, both at home and abroad. Meanwhile, what is to become a two-way traffic in strategic weapons - U-Boats and missiles - ties Israel and Germany together in opposition to Russia and Iran.

***

Thank you for reading this far. Putting out the newsletter is a rewarding project and I am delighted that it is read all over the world. But what keeps the project going is the financial support of readers like you. If you feel you can join the group of supporters, please click below and choose one of the subscription options. The price of a fancy coffee per month keeps the flow of quality content, going.

Thank you for your work and what must tremendous work hours.

Thanks for this. It’s helpful to read a post about the response to Gaza in Germany that I don’t simply like or dislike but that suggests a way of understanding, for better OR worse.