Chartbook 268: "How can we not know?": CAR and the challenge of tracking a silent crisis.

“An explosion of child deaths” - I will never forget coming across this phrase in a piece by Michelle Williams, the then dean of Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, in the FT in November 2022 on the occasion of COP27 in Egypt.

It was at a moment when many of us were discussing the polycrisis as a concept with which to grasp the current world. Was an explosion of child deaths the ultimate indicator of crisis?

With the war in Ukraine raging, what Williams was calling attention to was the lethal accumulation of risks happening at the same time in Africa, as a result of climate change, political conflict and the surge in food and energy prices.

The phrase, “an explosion. of child deaths”, came from Unicef’s Rania Dagash who in 2022 was warning of the risks to the people of the Horn of Africa. As Williams explained, tens of millions of vulnerable people in Kenya, Somalia and Ethiopia were at risk of starvation amidst one of the worst droughts in decades.

These were not empty words. In the spring of 2023 a new report commissioned from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Imperial College London and published by the Somalian Federal Ministry of Health & Human Services, WHO and UNICEF suggested that

an estimated 43 000 excess deaths may have occurred in 2022 in Somalia due to the deepening drought, a figure higher than that of the first year of the 2017--2018 drought crisis. Half of these deaths may have occurred among children under the age of 5. ….

And the crisis was far from over, as the report from the spring of 2023 went on to explain

For the first time, a scenario-based forecast model was developed from the same study to enable anticipatory action and avert drought-related deaths. The forecast, spanning January to June 2023, estimates that 135 people might also die each day due to the crisis, with total deaths projected to fall between 18 100 and 34 200 during this period. These estimates suggest that, although famine has been averted for now, the crisis is far from over and is already more severe than the 2017/2018 drought crisis.

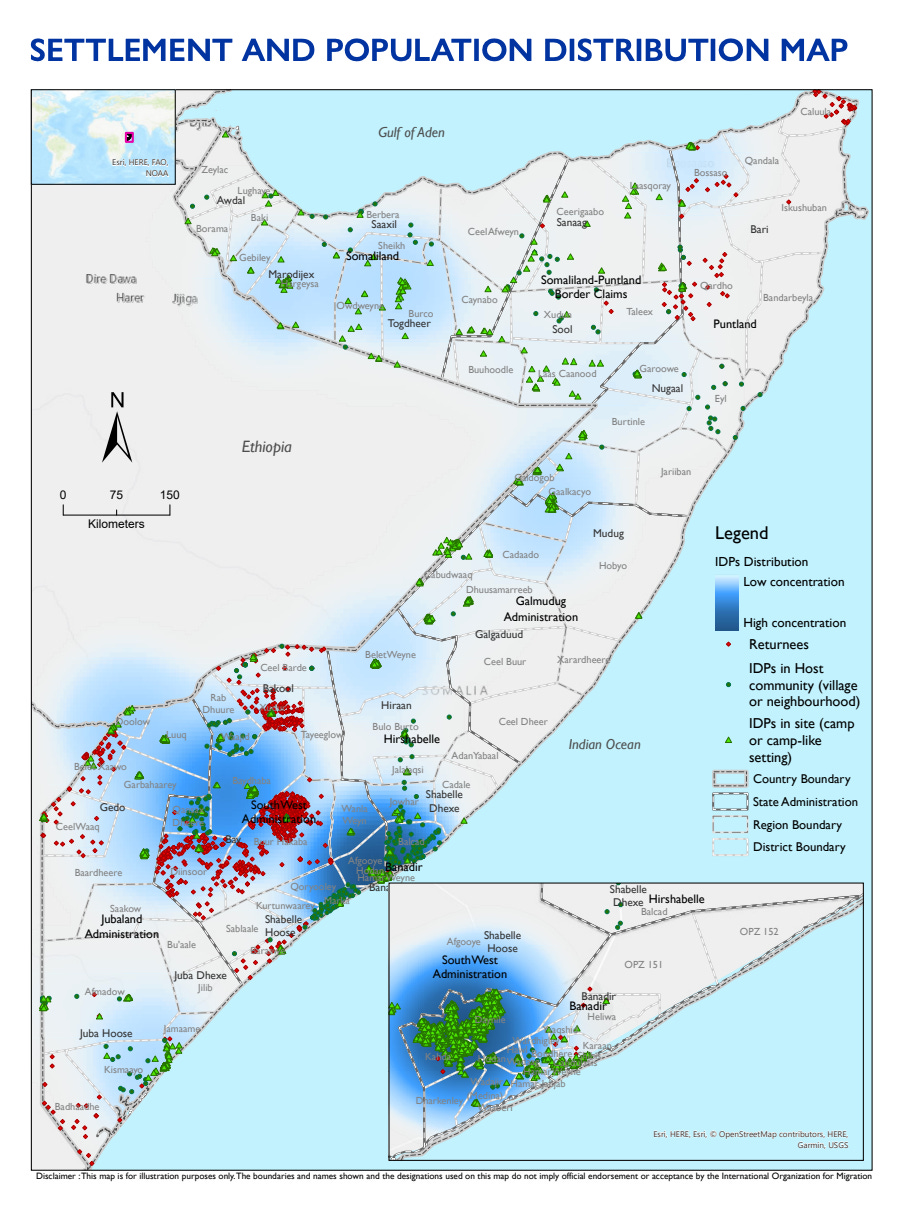

To compound Somalia’s misery, in 2023 drought was followed by unprecedented flooding. As of the time of writing, in early 2024 Somalia faces a humanitarian crisis of epic proportions.

This crisis is gigantic. It is woefully under-resourced. It is also plainly visible.

In the spring of 2023, with that phrase - “an explosion in child deaths” - still echoing through my brain, my attention was caught by another report, about another crisis in another region of Africa, this one defined above all by its invisibility.

***

The Central African Republic is one of the few countries in the world as desperately poor as Somalia. CAR’s GDP per capita is barely more than one dollar per day. Its life expectancy is 54. In the Human Development Index rankings, CAR comes fourth from last. Somalia is generally ranked bottom.

Source: Unicef

In 2013-2014 CAR suffered a violent civil war, which at one point overran the capital. Predominantly Muslim Seleka rebels ousted then-President Francois Bozize from office, triggering a response by Christian militias. For the last decade, approximately 70% of the countryside and one third of the population have been outside of the government’s control. Despite repeated peace talks between the 14 non-state armed groups, fighting is endemic. According to official statistics which are likely to be an underestimate, CAR has a population of barely more than 5 million people, compared to 17 million in Somalia. Unlike Somalia, CAR is landlocked and very inaccessible. Much of the CAR countryside can be reached only by river. Its agony remains contained. If the CAR attracts attention from the outside at all, it is because of the presence of Russian mercenaries. First reports of Wagner’s presence came in 2018.

With limited government control, and minimal infrastructure and public services, CAR may be the country with the worst medical records in the world. We know very little about how the people of CAR live and die. The shocking report that caught my eye in the spring of 2023 suggested that in the CAR this invisibility and silence may be hiding a spectacular explosion of mortality - a disaster even worse in proportional terms than that in Somalia.

***

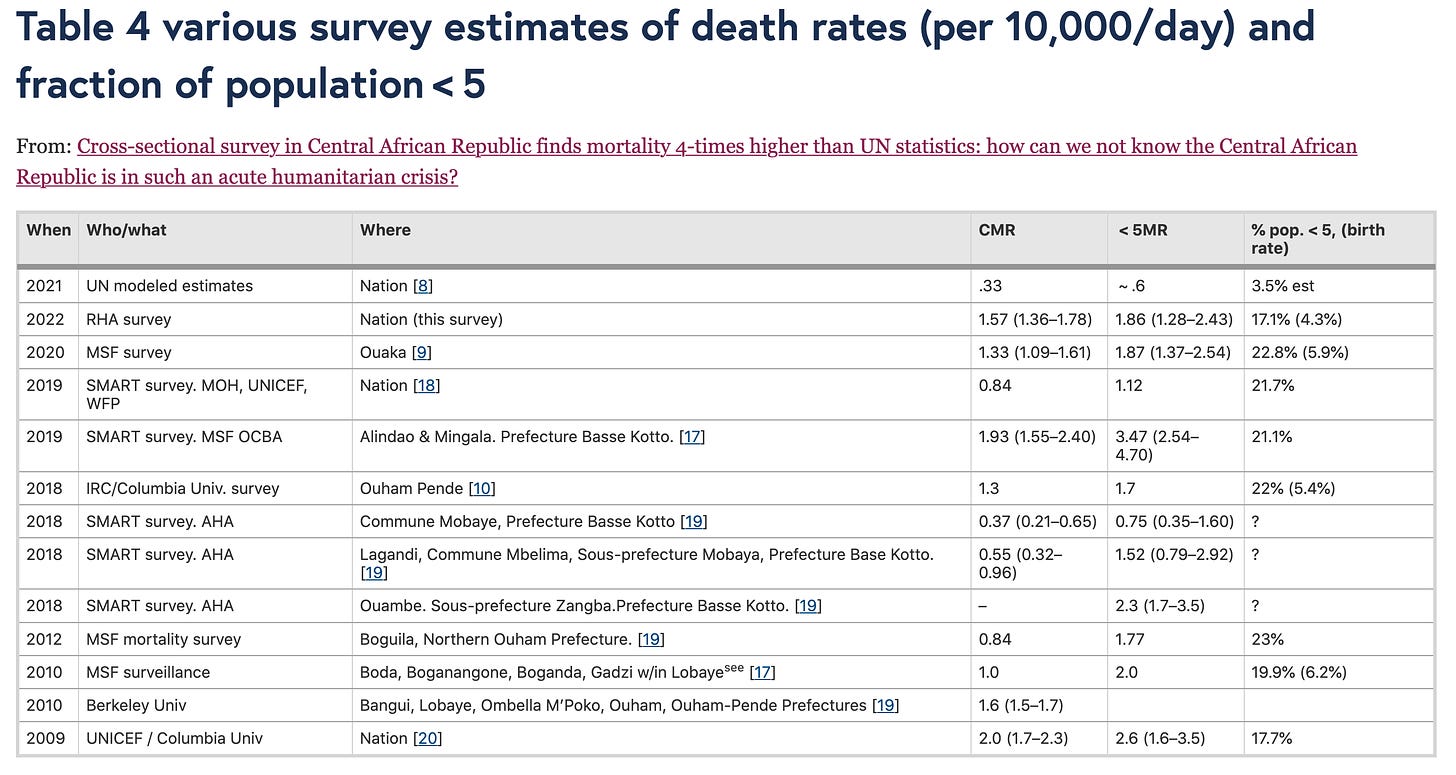

You would not be alerted to this if you followed the slow-moving demographic data of the UN. With their methodology based on expensive official surveys conducted a lengthy intervals, combined with projections of steady demographic trends, the UN data show CAR’s mortality and birth rate both declining. The UN reports the crude mortality rate for CAR as being on a par with Lesotho and Nigeria - at c. 0.33 per 10,000 people per day. Those figures are not great, but they are far from the levels that would trigger the declaration of a public health emergency. According to guidelines agreed by Centers for Disease Control in 1992, a country is suffering a public health emergency if its baseline mortality has doubled or exceeded the rate of 1/10,000/day.

But whereas the UN data were unexceptional, on the ground reports from charities that provide relief to the local population were by 2022 indicating something far more dramatic. Food scarcity was clearly rising. In 2022 UNICEF warned that food insecurity and malnutrition were widespread and threatened the death of tens of thousands of children. Visitors to rural areas reported a worrying absence of infants and small children. In the summer of 2023, the UN reported that:

the humanitarian situation in the Central African Republic (CAR) was critical, with more than half the population, 3.4 million people, requiring assistance and protection … Of this number, 2.4 million “have needs so severe and complex that their survival and dignity is at risk,” Mohamed Ag Ayoya, UN Humanitarian Coordinator in the CAR, told journalists in Geneva.

Concerned that the inadequate local reporting systems and slow-moving UN estimates were obscuring the full dimensions of an extreme and fast-moving disaster, a team of American and Congolese public health experts, together with local CAR collaborators, undertook a daring attempt to survey demographic data in both government-controlled and rebel areas of the CAR.

The team consisted of Karume Baderha Augustin Gang (first author), Université Evangélique en Afrique, Bukavu, DRC, a veteran of the controversial business of making demographic estimates in conflict zone. Jennifer O’Keeffe, a doctoral student at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Columbia Mailman alumna; a contributor from Bocaranga, CAR who preferred to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals and Les Roberts, professor emeritus of population and family health, Columbia Mailman School also a veteran of conflict zone demography.

As Amy Maxmen at Undark reports, Karume Baderha Augustin Gang is famous for having, 20 years ago, helped to conduct a mortality survey that revealed millions of deaths during the massive war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

A summary of the results for CAR released in the spring of 2023, can be found at Pubic Health Columbia. The full report is at Conflict and Health.

To conduct their research the investigators made use of the extraordinary fact that though much of CAR is inaccessible on the ground, all of it can be seen from space. Every single building in CAR can be identified and its coordinates precisely plotted by means of the Central African Republic Ecopia Building Footprint layer, ©2019 Digital Globe, Inc.).

Karume et al describe their methodology as follows:

For stage 2, we randomly selected an individual building from the image database for each cluster starting point. If no household existed at the assigned spot, the study team visited the nearest location with at least 10 households. If we estimated that we could not travel to and from a cluster within 10 h by motorcycle or car from where the team spent the night, or if insecurity was assessed to be extremely high, the cluster was skipped, or the nearest reachable village used as a substitute. We sought approval from Bangui and local administrative officials before visiting households in the clusters. We asked village or neighbourhood leaders if there had been any general population food distributions, and if there had been fighting between armed groups within 10 km of the village in 2022. We used GPS devices, phones, or in the riskiest areas, hand-drawn maps to identify the starting point of a cluster. Interviewers approached the 10 households nearest to the starting point. At each household, interviewers sought informed consent, by describing the purpose of the study, indicating there would be no direct rewards or benefits to participants and specifying that participation was completely voluntary. Interviewers sought verbal consent due to the low levels of literacy in most of CAR and the potential risk posed to interviewees if we sought written consent. If the interviewee agreed to participate, the interviewer signed a consent line on the data form.

All told, across CAR, they managed to interview 699 households, containing 5,070 people, in both government-controlled areas and those not under government control. No one was killed in the course of the investigation, though as Maxmen describes it the risks were all too real. The budget for the survey came to as little as $50,000.

The results are staggering.

***

Overall in 2022 the surveyed population of 699 households across the CAR were mourning the deaths of 220 people - 115 in areas beyond government control, 105 under government control. Allowing for new births, this yields a catastrophic crude mortality rate of 1.57/10,000/day.

In 2022, if the survey results are not wildly wrong, 5.6 percent of the population of CAR died - one in twenty people.

For sake of comparison, in the USA, 1 percent of the population dies each year and in the poverty-stricken and conflict-ridden DRC the figure is 2.5 percent. The CAR estimate, if it is supported by other research, would imply a death rate twice as high as any other recorded anywhere in the world.

What caused this extraordinary death rate, which is the equivalent of that suffered by countries involved in total war?

In the CAR, in 2022, active fighting was reported in 22 of 33 (66.7%) non-GC clusters, but in none of the government-controlled clusters. Of the 22 non-GC clusters with active combat, 19 local chiefs reported involvement with “Russian” groups. But, overall, armed conflict and other violence accounted for only 6 percent of all deaths. Overwhelmingly, the main causes of death were disease, with malaria (18-19%) and diarrhea (9%) topping the list. Disease was precondition by endemic hunger. 82.3 percent of households reported that adults were eating one meal or less per day and 72.6 percent of children were in this state of deprivation.

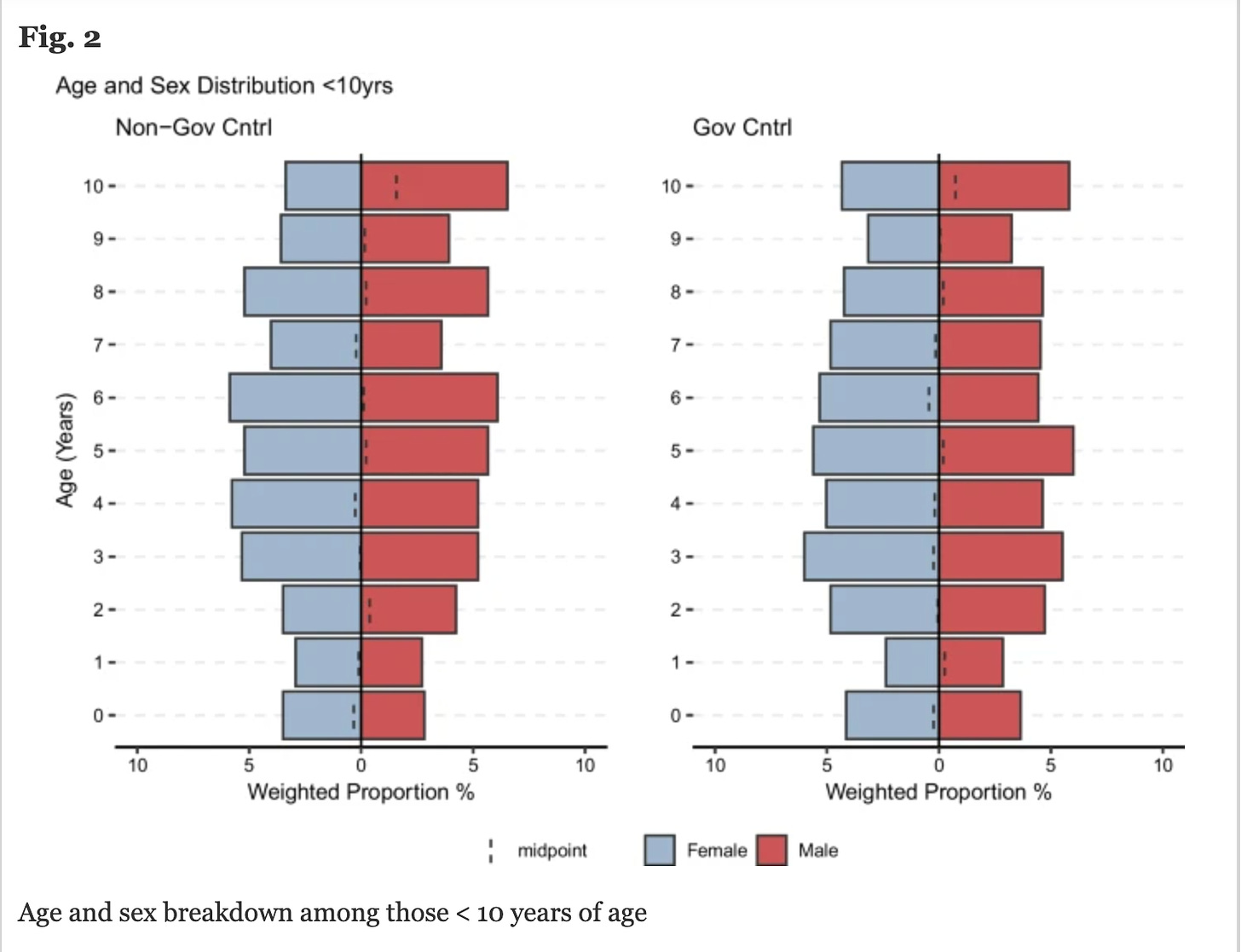

The survey confirmed the impression of recent outside observers that there is a dearth of young children in the CAR.

In the areas of CAR not under government control, the under-five mortality rate (U5MR) was a truly catastrophic 2.62 (95%CI: 1.63–3.61) compared to 1.08 (95%CI: 0.49–1.66) in the GC areas. The overall U5MR was 1.86 (95%CI: 1.28–2.43, DEFF: 1.04). This is an explosion of child deaths.

At the same time, women under extreme stress suffer a highly elevated rate of miscarriage. The questionnaire implied a miscarriage rate of 25.5 percent, which is higher than that recorded in neighboring Eastern DRC even in 2002 during a period of extreme conflict.

**

Clearly, a population survey conducted by way of sampling at “arms-length” is not the ideal way to obtain demographic data. Since the publication of the results, the CAR government has expressed outrage that it did not authorize the survey and has contested its results. But it offers no evidence to counter the claims being made. To address the ethics issue, the investigators took the precaution of approving the methodology of the survey with The Comite National D’ethique de la Sante of the DRC Ministry of Health.

The data has also met with resistance from the United Nations population division, which rejects the results as excessively dramatic. But the UN has no obvious alternative but to rely on outdated and unreliable official surveys.

As the authors of the 2023 paper comment:

The 2010 MICS survey done jointly with UNICEF and the Bangui Government, which produced the last official UN CMR national estimates we have seen, sampled only areas controlled by the government, and only from villages reachable by vehicle. In rural areas of our survey, teams with motorcycles were 2.6 times more likely to reach the sampled location than a vehicle. Further undermining the 2010 MICS survey’s credibility are reports that in some places interviewers were accompanied by armed military escort, an act which would refute any claim of neutrality in the findings. (LR personal communication with MICS 2010 interviewers who later worked for him on Ref. 26).

The UN’s estimates of CAR mortality have been exposed as optimistic by a range of alternative estimates carried out by independent researchers.

As Anna Kuehne and Leslie Roberts commented in 2021, the UN data are riddled with implausible assumptions:

The UN estimates a crude mortality rate (CMR) of 11.3/1,000/year, and a birth rate of 34.5 births per 1,000 per year population in 2020 [9]. The UN mortality statistics indicated a steady decline of crude and under five mortality rates (CMR and U5MR) over decades , even through the deadly civil war period in 2013–14 when more than one fifth of the population fled their homes and bodies covered the streets of the capital city. This reported steady drop in all cause CMR and U5MR from 2012 to 2013 to 2014, provides a striking insight into the inability of modelling-based data to capture the reality in this conflict-affected setting.

As Anna Kuehne and Leslie Roberts go on:

Many assumptions used in modelled estimates, including that birth and deaths rates change steadily over 5 year periods, are inappropriate in conflict settings. The nature of conflict settings is inevitably volatile, suggesting that only very short-term and limited assumptions may be suitable. With pressure to show progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, both the UN and the Government are in a challenging position. Both are invested in the conflict; the Government directly over control of its own sovereign territory and the UN in support of the Government, and through its Peacekeeping mission. It may be that host governments and the allied United Nations that support them are not capable of producing reliable mortality estimates during conflicts.

Beyond the specifics of methodologies used there is a basic question of how demographic monitoring can respond to “explosive” crisis.

Though the CAR suffers from chronic poverty and violence one should not reify that distress into a permanent and unchanging condition. There was a clear sense among respondents to the 2022 that the situation had become dramatically worse over the previous two years. In the government-controlled areas the most commonly cited shock was COVID. In the rest of the country the issue was the upsurge in violence.

The government employed the Wagner Group to regain national territory after a decades-long hold by rebel groups.

There have been widespread human rights abuses by the Wagner group in these efforts, including public executions, massacres, and rape as a weapon of war, mainly in areas thought to be rebel strongholds [4, 27]. This has had the effect of driving armed combatants to more frequent and severe confrontations with civilians in order to survive. Dozens of households in the Non-GC areas described not being able to travel to visit their fields, hunt, fish or forage for survival because combatants would attack or kill them.

***

The sub-title of the CAR report is: “How can we not know?” It is a powerful question and an urgent one.

The worst effects of polycrisis make themselves felt directly on the bodies of the most vulnerable people in the world - children in the poorest parts of Africa.

A complex political economy and geopolitics governs which crises are”visible” and which “invisible” to the wider world, which crises are loud and which crises are silent, which crises “matter” and which “do not”. It is no coincidence that the CAR, one of the world’s poorest and most fragile countries, may also be the nation with the world’s worst official health statistics.

Visibility matters because we live in a world that is model- and data-driven. What is counted counts.

In poor places with very bad infrastructure and ongoing conflict, large-scale best-practice official data gathering apparatuses may systematically fail to capture the reality of chaos, distress and death, thus understating the extent of crisis. Governments and external agencies are invested in delivering good news on the sustainable investment front.

Small scale, sophisticated and nimble interventions by coalitions of NGOs and experts may provide a useful check on the resulting blindspots.

As Karume Baderha Augustin Gang demonstrated with the pioneering work he helped to produce for DRC, better information can change global discourse. His family paid the price, suffering brutal reprisals. The least we owe these brave knowledge-workers is recognition, solidarity and amplification.

And from all this there is surely one simple message. The people of the Central African Republic need and deserve more help. This is what the the questionnaires also showed. People in sometimes remote villages meeting statistical investigators and when given the chance by an open question asking for food and medical care.

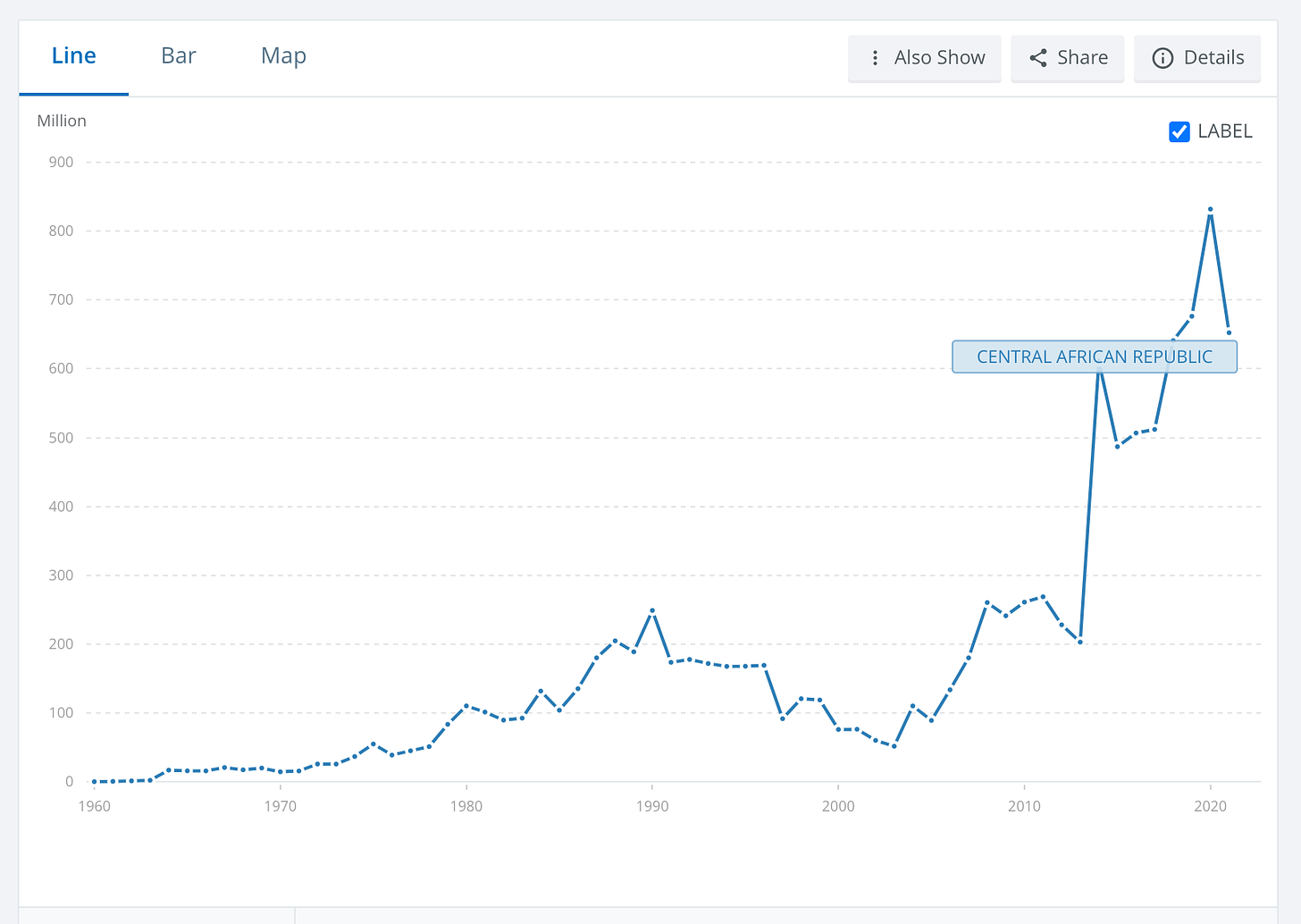

Figures from the World Bank show a surge in foreign assistance and aid to CAR since the early 2010s.

But at the current level, this aid amounts to no more than $120 per person. In the face of what may be the most severe mortality crisis in the world, it is a shamefully inadequate response.

**

To support Chartbook click here

I submit that the polycrisis and the resulting danger and underdevelopment in the Central African Republic and far too many other places are the inevitable product of our reigning culture of indifference, or downright opposition, to the well-being of others.

We need to replace the ethos of competition with standard-of-living-focused solidarity, economic sharing and cooperation, and non-violent dispute resolution.

A hypothetical of sorts:

A state, national or society is invaded and conquered.

This is done in a context in which borders are created that fully ignore the relationships of the people living there.

The preexisting state and society are completely destroyed, the people complete subjugate except for such native leaders who might be co-opted to serve the conquerors.

After some period of maximum exploitation and literal extraction, the conqueror walks away without preparing the conquered people for independence, without in any meaningful way filling the vacuum that created by the conquest.

The conqueror and their allies then continue the exploitation by other means.

So. How does one expect anything but something of a disaster, at least by western standards?