Chartbook 262 Crisis Tribes - On Europe Now

Revisiting the politics of trauma in Europe’s election year

Over the past 15 years, Europe has experienced five major crises. The climate crisis forced Europeans to imagine a world in peril. The global financial crisis led Europeans to doubt their children would enjoy living standards better than their own. The migration crisis triggered an identity panic that centred on questions of multiculturalism and the meaning of nation-states. The covid-19 pandemic exposed the vulnerability of our health systems in a globalised world. And the war in Ukraine shattered the illusion that major war would never return to the European continent. These five crises have several things in common: they were felt across Europe, although to varying intensities; they were experienced as an existential threat by many Europeans; they dramatically affected government policies; and they are by no means over.

Several folks have tried to map these shocks and their interactions using the idea of polycrisis.

For me unlike for some analysts the polycrisis idea has always been first and foremost about mapping a cognitive shock, rather a well-specified model. The phrase captures what Michael Geyer described to me as a “knowledge crisis’.

So I find very congenial the impulse of Mark Leonard, Ivan Krastev and a team of researchers commissioned by the ECFR to explore the question of who experiences which crises how. You can read a short version in the Guardian, from which I quote above, and download the full research with the evocative title - A crisis of one’s own: The politics of trauma in Europe’s election year - from the ECFR, here.

***

As they outline their case.

an underreported feature of the polycrisis is that for different societies and for different social groups one crisis usually plays a dominant role above others. French president Emmanuel Macron captured this well when he contrasted those who worry about the end of the month (economic crisis) with those who worry about the end of the world (climate crisis).

Krastev and Leonard go on to add the rather interesting suggestion that in picking our crises we define ourselves.

That is what we mean when we say that everyone wants a crisis of their own.

Show me your crisis and I will tell you who you are.

To investigate this question, the ECFR commissioned worldwide opinion polling which I will report on in a subsequent newsletter. If we focus on Europe, each one of the five crises - climate, war, economic insecurity, immigration, COVID - picks out a distinct constituency for whom this is “The Crisis” of the moment.

The ECFR polling allows these constituencies to be mapped across Europe and to be broken down by demographics.

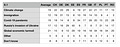

The following were the answers given to the question: "Which of the following issues has, over the past decade, most changed the way you look at your future?"

Source: ECFR

Germany stands out for the priority given to immigration by almost a third of the respondents, a share twice as high as in France and Britain and three times larger than in Italy.

Denmark, Estonia and Poland have unsurprisingly been shaken by Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

In Italy and Portugal the after-effects of the GFC and eurozone crisis are deeply felt. This is where the politics of trauma invoked by Krastev and Leonard really comes into play.

COVID comes in first place in Spain, Britain and Romania.

In France and Denmark the climate crisis tops the list of shocks. 27 and 29 percent of the population put the issue first, compared to 6 and 11 percent in Estonia and Poland.

***

The most dramatic findings are on the immigration tribe.

As Krastev and Leonard comment:

The current preoccupation with migration does not come from the fact that most people in most countries are obsessed with it, nor from the fact that it is the most divisive issue in societies. In reality, we are witnessing the emergence of a kind of migration consensus all over Europe: support for strengthening external borders has become commonplace among political parties. But what singles out the “migration tribe” - those who define migration as The Crisis - is intensity. They are the angriest of all at EU policies and their anger pushes them to the right.

The immigration tribe are classic populists in believing that their crisis has been very poorly served by “those in power”. The only other group with a similar sense of failure are the economic crisis tribe. But the intensity of their disappointment is half that of the immigration tribe.

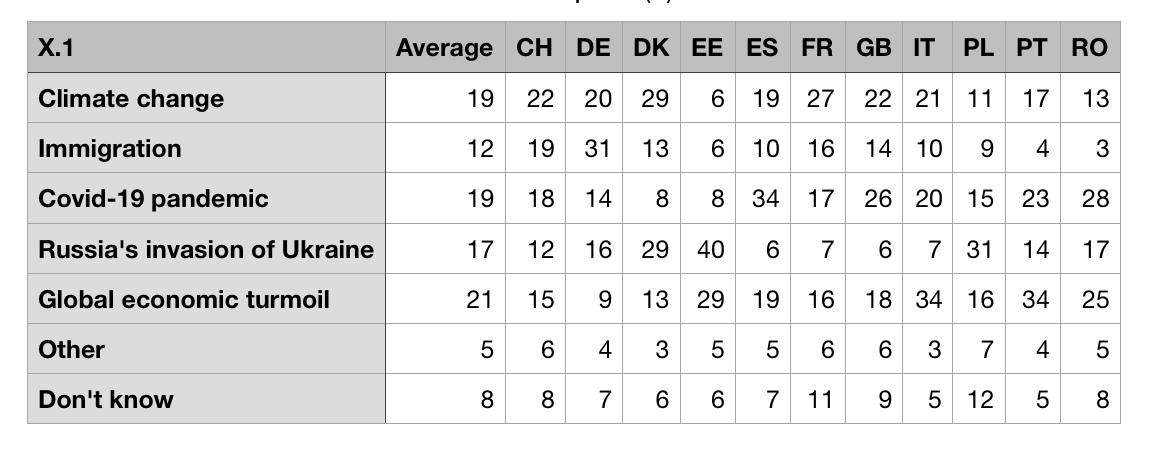

Unsurprisingly, those who prioritize the immigration issue strongly favor far-right parties. But not only that. Amongst French voters no other issue is as strongly linked with a particular party affiliation. By contrast, climate-concerned French voters are spread across the parties. Le Pen’s party picks up almost as many climate voters as do the Greens.

The same pattern is seen in Germany. The “immigration tribe” skews massively to the AfD and CDU.

The difference in Germany is that climate concerns concentrate a solid block of support around the Greens. Meanwhile, the CDU scores heavily amongst those concerned principally with national security issues.

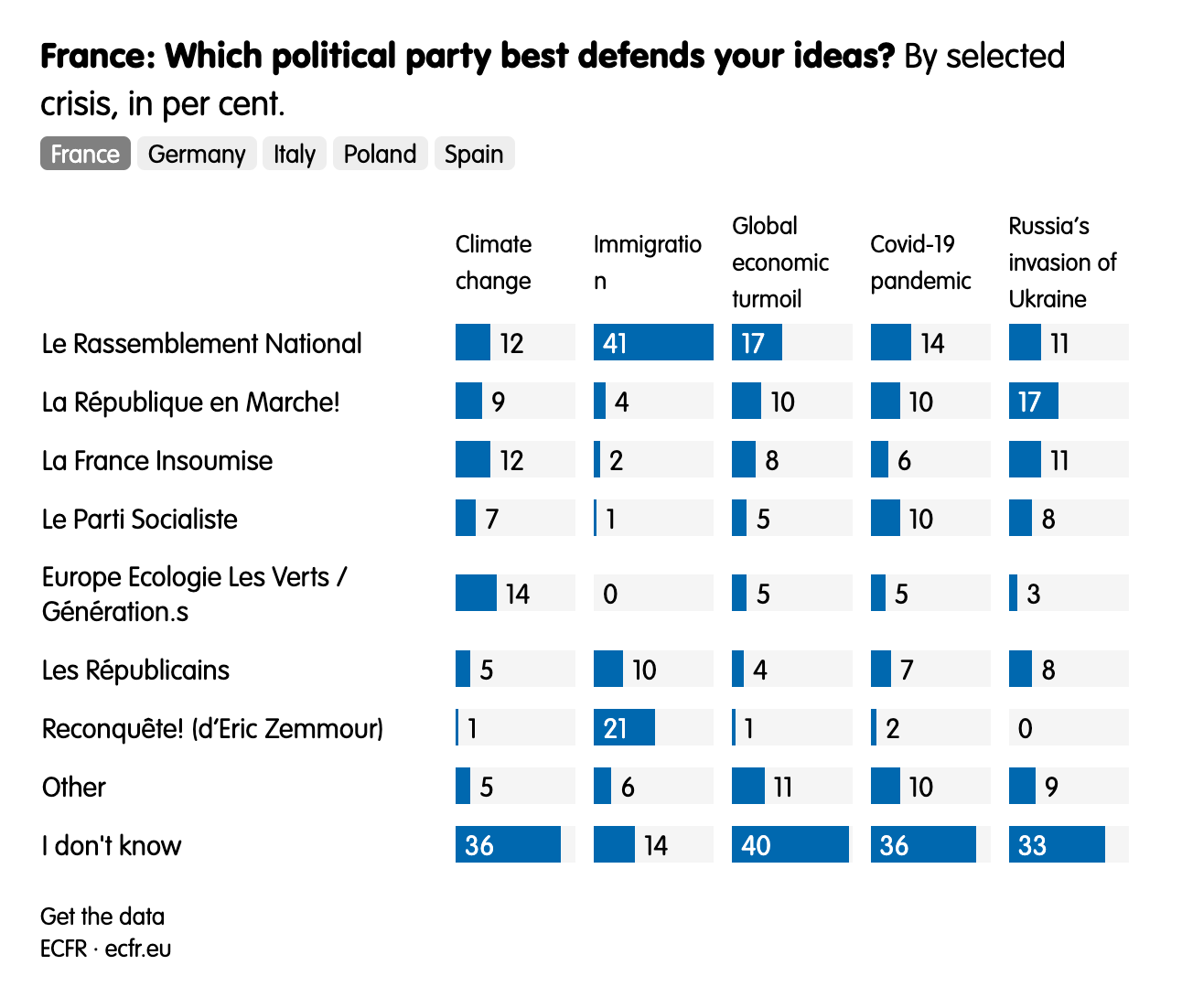

In Germany, the economy comes far down the list of priorities. But where do those concerned about the economy go where it really matter? The striking conclusion from the Italian data, where the issue is #1, is that this constituency feels politically homeless.

Of the one third of Italians who say that the economy is their top issue, Meloni’s party comes top, but 47 percent say that they will either not vote or don’t know which party to vote for. In France, likewise, amongst those concerned about the economy 40 percent don’t know which way to vote. The left has no advantage on the economic issue, either in France or Italy.

On the disaffection of the economy tribe, Krastev and Leonard remark rather coyly:

This could potentially be explained by the absence of any major difference between the austerity policies adopted by right-wing or left-wing governments in 2009-10. Rather than reinforcing the left-right divide, the economic crisis may have reduced its salience. Over the course of the different crises, countries that had incumbent centre-left governments replaced them with centre-right parties, and vice-versa. So, the members of the economic crisis tribe are in a sense mostly classical protest voters.

As far as the upcoming European elections are concerned, Krastev and Leonard predict a two-way fight:

The climate tribe is the mirror image of the migration one, with its members often supporting green parties or centre-left parties. It is the clash between these two tribes that will define the upcoming European elections.

***

These two issue-based constituencies on immigration and climate share some features.

One might suppose that a common characteristic of both the climate and immigration tribes is that they are particularly sensitive to the temporal dimension of politics. They believe that if specific actions are not taken today, they will become impossible to implement tomorrow. They share the sentiment that we live on borrowed time.

But they also differ in quite fundamental respects.

Interestingly, however, our polling suggests that these two crisis tribes experience very different dynamics once their preferred parties are in power. When the migration tribe sees right-wing parties in power, its adherents tend to become more relaxed about the issue. In Italy, immigration is surprisingly low among the concerns of many voters: just 10 per cent of the country’s population, and only 17 per cent of Brothers of Italy supporters, describe it as their most transformative crisis, regardless of the fact that the Brothers of Italy was elected on a strong anti-immigration platform. … The climate tribe behaves in the inverse way. Our polling in Germany shows that people continue to worry about the climate crisis even when their government has a strong climate programme; they do not consider the problem resolved. In short, voters may perceive electing a far-right government as the answer to immigration fears – even if little changes in reality – but they do not consider the climate emergency over after electing the Greens.

But whereas right-wing voters are easily pacified by the belief that “their people” are in charge. Over the long-run their outlook differs quite fundamentally from that in the Green camp.

This distinction was clear from some German data that I reviewed in Chartbook 235 in the summer.

Asked whether they believed that Germany was headed towards a very big crisis which could be solved only through system change, Green and AfD voters took polar opposition positions. Whereas 62 percent of AfD supporters agreed that a radical change was on the cards, 68 percent of Greens took the opposite point of view.

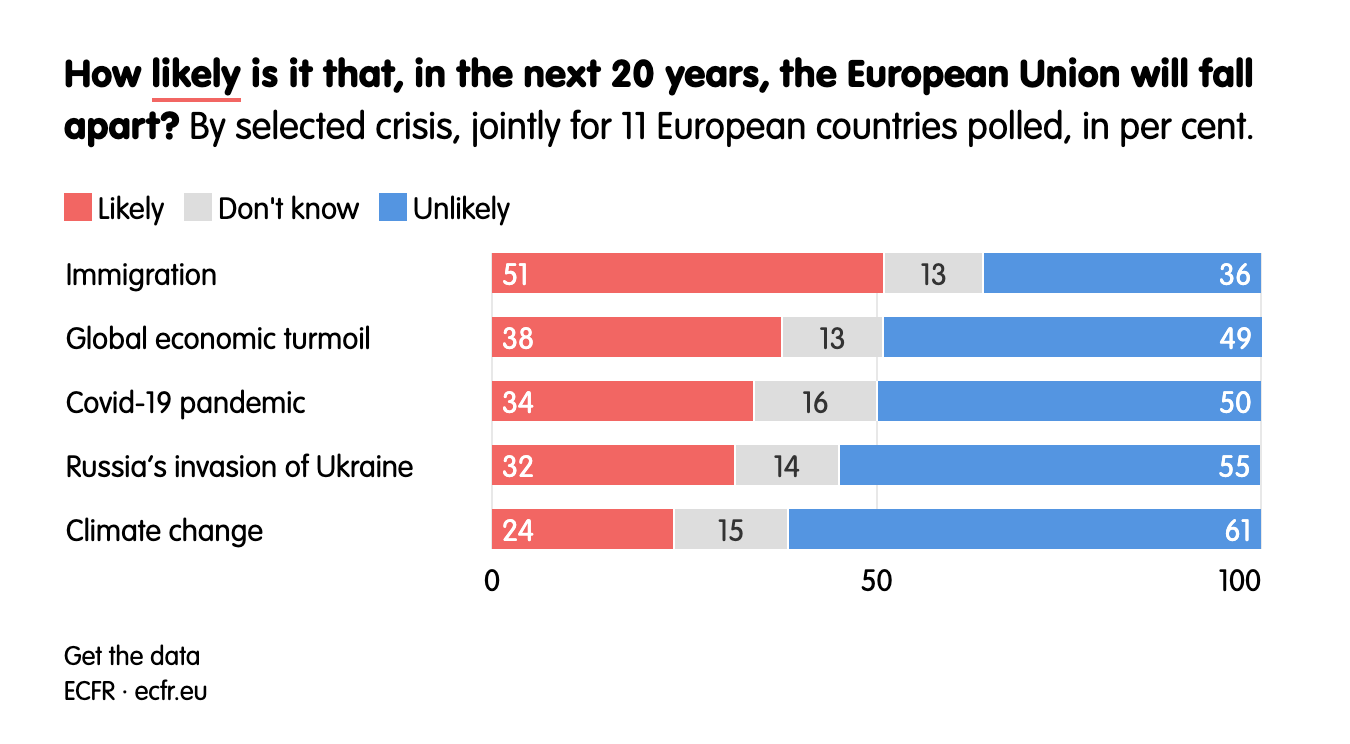

In the ECFR data we find the same pattern as revealed by the question: Do you think it is likely that the EU will fall apart in the next 20 years.

In the immigration crisis camp, 51 percent expect the EU to collapse. In the green climate camp that share is 24 percent.

Sensible green-minded folks might conclude that they are fortunate in holding a rational outlook and belonging to a mobilized constituency that will secure an important voice in any proportional representation system. Less complacently we should also surely wonder why the constituency is not wider than it is and question whether that might have to do with the intensely technocratic can-do managerialism that seems to unify the climate camp and the failure to gain traction on wider economic issues.

***

This post is part of an occasional series On Europe Now.

Chartook 260 and 261 address the situation of the Eurozone.

Chartbook 260 was originally mis-tagged as Top Links and thus may not have been fully accessible to everyone who wanted to access it. I have fixed that snag.

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Really interesting result about anti-immigrant voters feeling a loss of urgency about that issue once "their" people get into power. This suggests they're more motivated by the issue as a means of gaining power, rather than any sincere concern.

You see that here in US, with many Republicans strongly opposed to any immigration deal because they want the issue, they want the crisis, much more than they'd want any policies that might respond to the crisis.

The question I would have for anyone caught up in the current anti-immigrant hysteria is "In what way has this new influx of immigrants hurt you, personally, or your quality of life?" Sure, if you're managing a homeless shelter in NYC or Chicago, this is truly a crisis for you. But how has a farmer in Iowa seen any negative effects from it? So if the farmer in Iowa is worked up into a rage about it, maybe it's because he sees that rage as being in service to his "team", the Republicans.

I have the idea that there is an archetypal pattern saying: if times are threatening or problematic, less people want to be responsible, as is really the demand in a democracy, and more people want to have a strong leader, to have someone to blame when things go wrong.

Really surprising that Italy is not more worried about immigration, but consistent with the extreme right in power.