As our collective attention pivoted in October 2023 to the violence in Palestine, one sharp-eyed correspondent remarked to me pointedly on our failure to pay attention to the huge violence that had unfolded in Myanmar, violence much of which is also directed at Muslims, notably the Rohingya in Rakhine state, bordering Bangladesh.

The corrective is well merited. The scale of the violence in Myanmar is spectacular. Currently about 2 million people are displaced. The Rohingya refugee complex in the Bangladesh region of Cox’s Bazar, just across the border, is often described as the largest refugee camp in the world. In a world of mass displacement that is a big claim.

Myanmar is a patchwork of ethnic groups that in many cases have been caught in violent struggle for decades. The dominant force in the country since independence has been the military, which between the 1960s and the late 1980s imposed a socialist regime, and have since migrated to a crony capitalism. In 2011 they embarked on a program of opening up that led to election of a democratic government. It was on its watch that the most violent campaign against the Rohingya was launched in 2017. In February 2021 the generals seized back control, deposing the democratic government in a coup. This has triggered armed resistance, not just in Rakhine, but in the border regions adjoining Thailand and China.

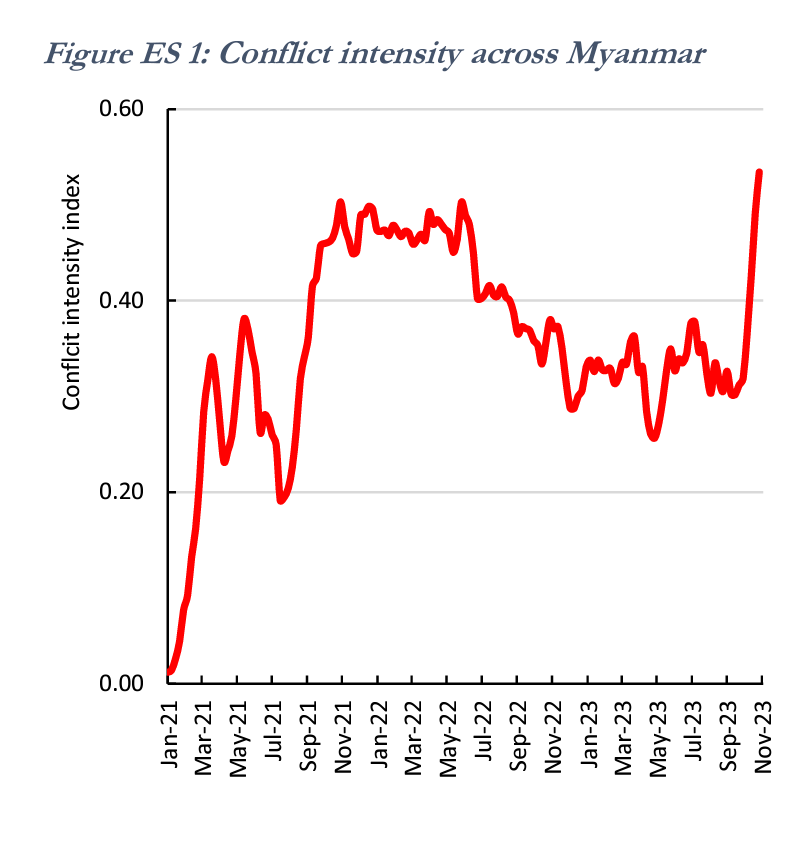

On the face of it, it is an unequal fight with the military controlling the major urban areas and much of the modern economy and enjoying the backing of China and Russia. But in October of this year, in the latest escalation of violence, armed factions in three major regions launched a simultaneous attack in what has become known as the 1027 offensive. The regime was knocked onto the ropes, whilst, as measured by the World Bank, the fighting has been more intense than at any time since the February 2021 coup.

Source: World Bank

The civil war has spread disorder throughout the region with large-scale criminal gangs operating out of the Golden Triangle. Meanwhile, the regime’s extreme violence has provoked accusations of genocide, profoundly embarrassing ASEAN, the regional economic organization. The fighting disrupts border trade and further damages Myanmar’s fragile economy.

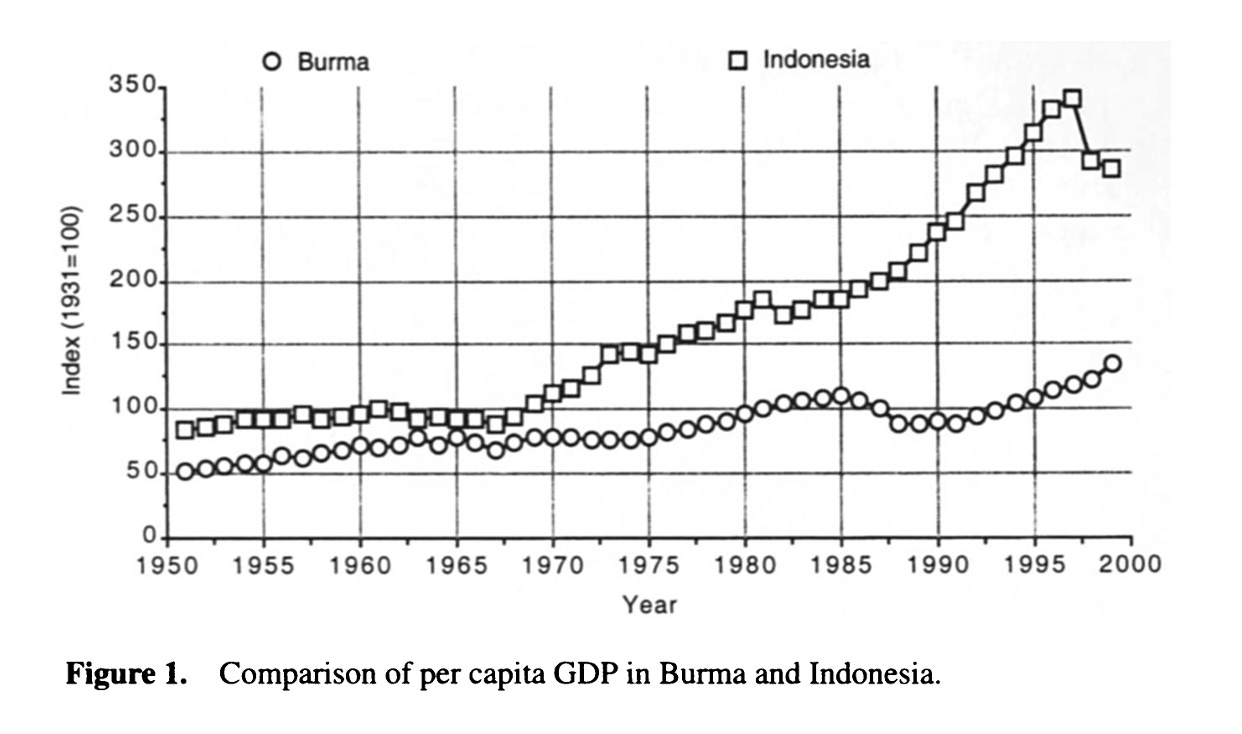

Myanmar, is a true economic disaster. Burma was once the rice bowl of Asia, the largest rice exporter in the world. During the great depression of the 1930s, Burma suffered a devastating agricultural depression and following the Japanese occupation and World War II, in the post-colonial period, the country never got back on track. From 1960 onwards it was subject to a brutal experiment in authoritarian socialism, led by the military.

Source: Anne Booth South East Asia Research 2003

By the 1970s, Myanmar had been reduced to one of the poorest countries in the world. Still today, Myanmar’s gdp per capita is lower than that of Vietnam, Laos or Cambodia, which suffered the catastrophes of the Vietnam war and the Pol Pot regime.

In 2011, a political and economic transition process began. A transitional military government staged elections in 2015. As trade opened up and foreign capital flooded in, Myanmar experienced economic growth averaging 6 percent per year, coupled with significant reduction in poverty. One of the major growth sectors, following the example of countries like Bangladesh was the garment industry.

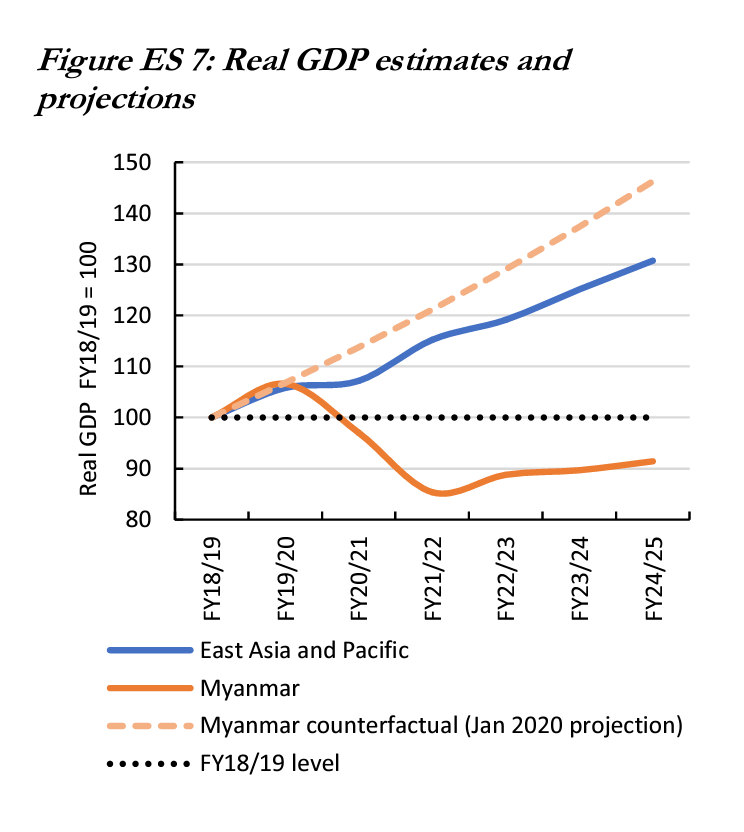

But this growth was set back by the fallout from the massive violence in Rakhine State unleashed in 2017, the COVID pandemic of 2020 and the February 2021 coup. In addition, natural disasters continue to ravage Myanmar. Cyclone Mocha, a Category 5 cyclone that struck in May 2023 did serious damage.

According to the World Bank survey of Myanmar: “The economy in 2023 is estimated to be 30 percent smaller than it might have been in the absence of COVID-19 and the coup. Real GDP per capita is estimated to be around 13 percent below 2019 levels.”

The current escalation of violence means that Myanmar’s economy is now under even more intense pressure. According to the World Bank: “In the Myanmar Subnational Phone Survey (MSPS) conducted at the end of 2022 and early 2023, about half of surveyed households reported a decrease in incomes over the past year, while only 15 percent reported an increase.” And the impact of the current crises is to further reduce the potential for long-run growth: “Public spending on health and education has fallen from 3.6 percent to about 1.8 percent of GDP between fiscal years 2020 and 2023.” The latest World Bank survey (May 2023) found that “48 percent of farming households worry about not having enough food, up from about 26 percent in May 2022. The survey also shows a notable drop in the consumption of nutritious foods such as milk, meat, fish, and eggs.” Roughly a third of Myanmar’s population is currently in need of relief aid.

In situation’s of crisis like this, the last resort of Myanmar regional elites and poor farmers it to retreat into various kinds of illegal activity. On the border to China, violent gangs engage in kidnapping thousands of Chinese workers into organized scam activity. Meanwhile, in the legendary Golden Triangle, the drugs trade is booming.

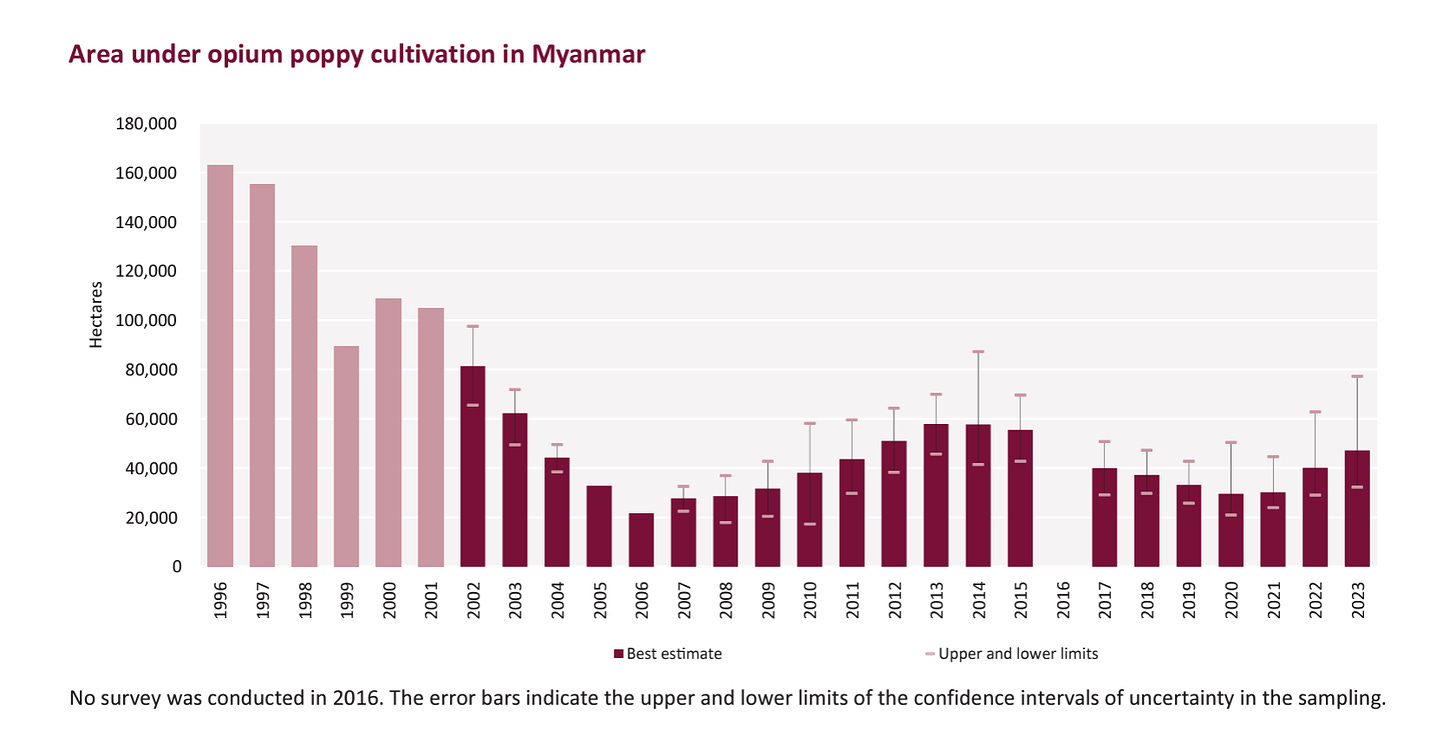

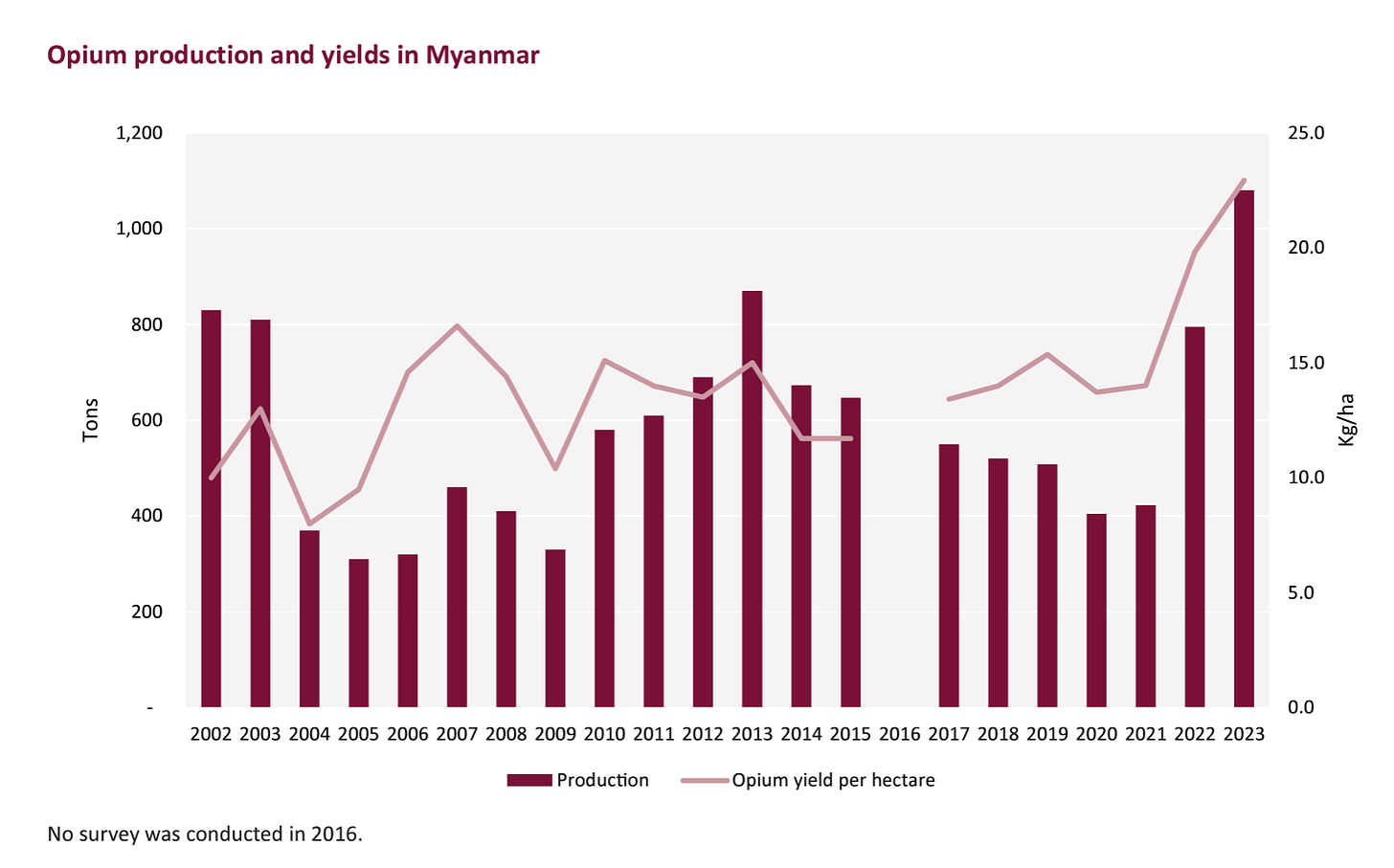

The drug trade is a continually shifting, global business. The Golden Triangle itself has undergone dramatic change. The area under opium cultivation is well down on its historic highs in the 1990s.

In the 2010s the focus of drug production shifted from opium poppies to various types of synthetic drug, which first began to feature prominently in the Golden Triangle in late 2013. Following the 2021 coup and the loss of control by central government over much of the border region of the country, synthetic drug production has continued to ramp up. Huge seizures of methamphetamine in the form of tablets and crystal meth reveal the scale of activity. But the Triangle has also returned to its roots with a surge in opium farming.

One factor driving the return to opium, is the crackdown in Afghanistan by the new Taliban regime, which has slashed opium cultivation by 95 percent since the Americans pulled out. By default Myanmar has become the biggest opium producer in the world. But the fact that the Golden Triangle is ramping up production also reflects the collapsing condition of the Myanmar economy. Powerful drug groups are entering the region offering seeds, fertilizer and even irrigation and sprinkler equipment. Impoverished peasants have no means of resisting their demands. Significantly, the crop yield has surged far more dramatically than the extent of cultivation, suggesting an improvement in farming techniques.

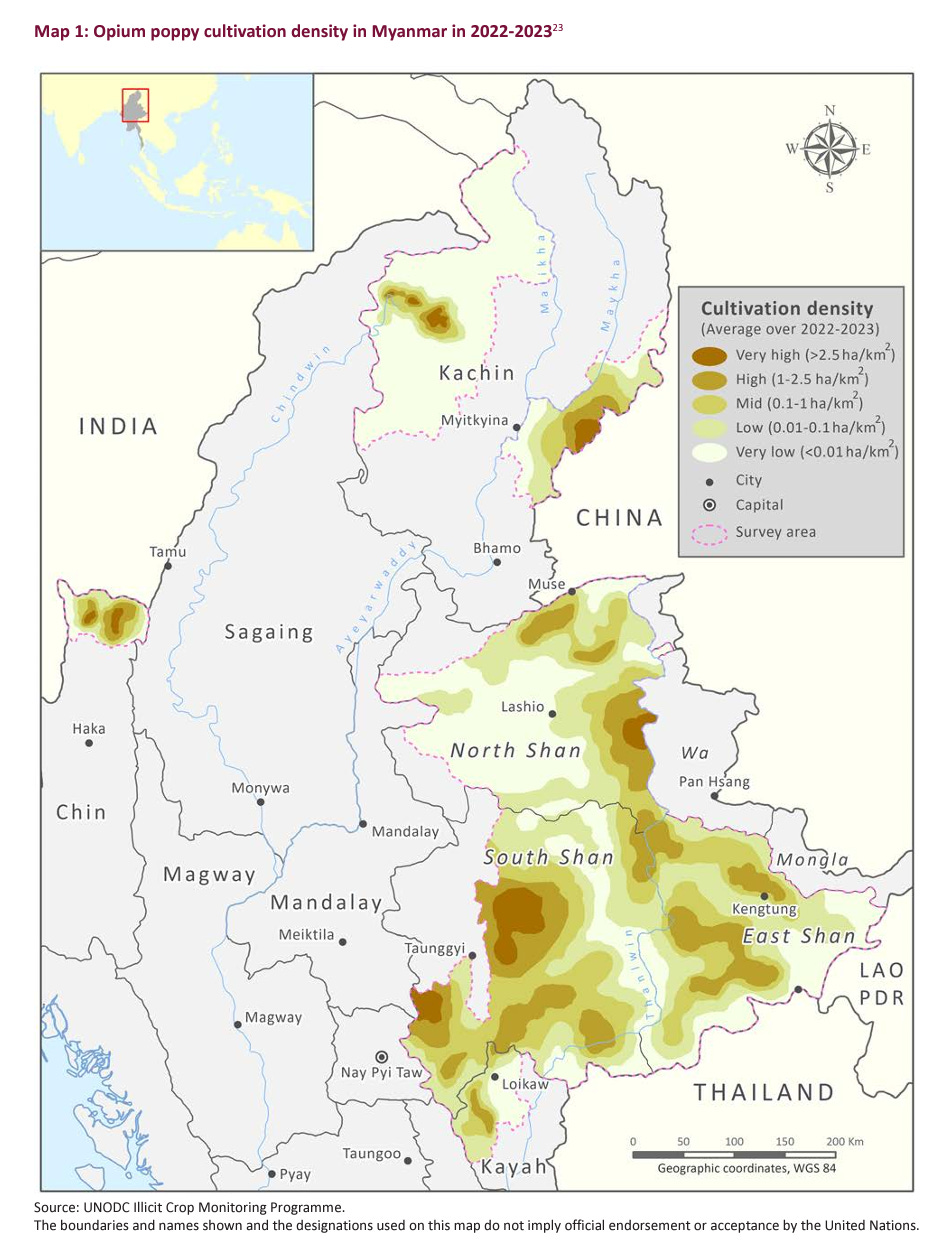

The money from the drugs trade flows out into the wider economy, driving large-scale money laundering activities in the casino business. The regional pattern of drug production is telling:

In Shan state, these post-coup conditions have created a “perfect storm” for drug production, according to Jeremy Douglas, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s (UNODC) regional representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific. “You have the breakdown of security in Shan state, an acceleration [of drug production] post-coup, and a massive and very porous border along the Mekong river between Shan and Laos,” he told Al Jazeera. “It’s a recipe for disaster.”

Source: UNODC

The drugs are not consumed in Myanmar but flow out to the international customers above all through the border to Laos, the “path of least resistance”. In October 2021, Laos police conducted Asia’s largest-ever drug bust, intercepting a beer truck in Bokeo province carrying 55 million methamphetamine tablets and 1.5 tonnes of crystal meth. According to UNODC Laos in 2022 seized 144 million meth pills. In 2019 and 2020, this figure stood at just 17.7 million and 18.6 million respectively. Across the region, in 2022 the authorities may have seized as many as 1 billion meth doses.

The drug economy is important in the border regions of Myanmar, in sustaining regional power bases and in fueling paramilitary activity. But as a means of prosperity and economic growth its potential is limited. According to the UN:

In 2023, the role of opiates in the Myanmar economy continued growing in importance. The farmgate value of opium is an important measure of the gross income of farmers generated by opium poppy cultivation. In 2023, it was estimated to range between US$271 and 613 million, representing between 0.5 and 1% of the 2022 national GDP, and between 2 and 5% of the agricultural, forestry and fishing component of the 2022 GDP, which was estimated at US$12 billion.7 Between 2022 and 2023, the farmgate price increased some 60%. The most profitable activity in the opium economy is heroin production and trafficking. In 2023, it was estimated that 5.8 tons of heroin were consumed in Myanmar, with a value ranging between US$104 and 197 million. Between 58 to 154 tons of heroin were exported, with a value between US$835 million and 2.2 billion. The gross value of the entire opiate economy – comprising both the value of domestic consumption and exports of opium and heroin – in Myanmar in 2023 was estimated to be between US$1 and 2.5 billion, accounting for about 2-4% of the national GDP in 2022.

All told the regions in which opposition to the Junta regime is strongest, account for only a relatively small share of Myanmar’s GDP. The provinces of Sagaing, Northern Shan, Rakhine, and Kayah accounted for about 17 percent of Myanmar's GDP in the fiscal year 2021-22.

Clearly, the vast majority of Myanmar’s population of 54 million live and work in other areas, most of which are under the grip of the Junta, which controls most of Myanmar’s airports, banks and big cities, including the capital, Naypyidaw.

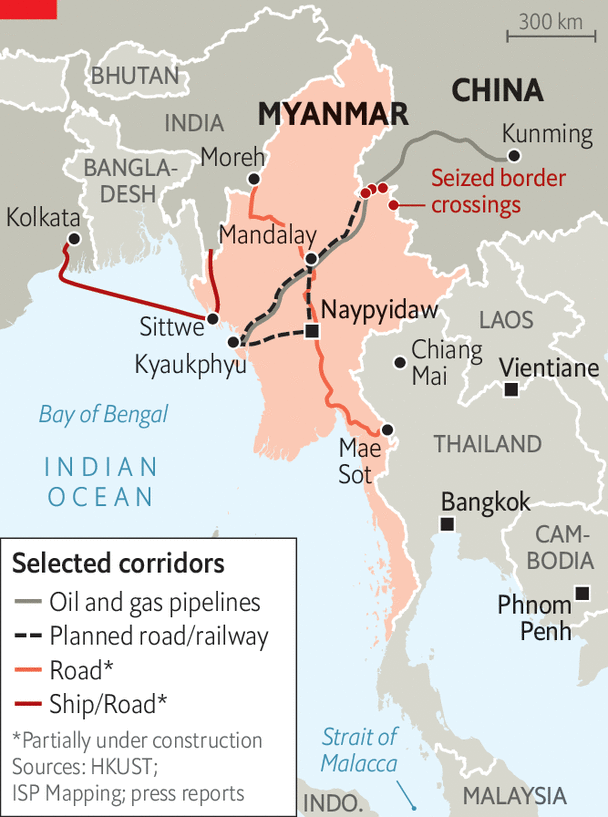

Given Myanmar’s strategic location, the obvious trajectory for its economy is to serve as an interface between China, the South East Asian regionC and the Indian Ocean.

Source: Economist

China would certainly love to develop Myanmar in this way. China sees Myanmar and the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor as an alternative to the choke-point of the Strait of Malacca, through which most maritime trade to and from China flows and which is under US naval control. Local Burmese political actors are only too aware of this fact. Like all players in the region, the Myanmar political elite are both orientated towards the riches and power of China and cautious about its overbearing influence. The Burmese military are at times borderline “Sinophobic” in their allergy to excessive Chinese influence. In recent years this has increased their desire to strength relations with Putin’s regime in Russia.

Ironically, during the period of Myanmar’s liberalization in the 2010s, Aung San Suu Kyi, the democracy activist who became de facto leader of the country in 2016, cultivated close relations with China, specifically to distance herself from Myanmar’s military. Beijing’s support was particularly useful after Suu Kyi’s government found itself under fire from Western critics over the genocidal violence against the Rohingya.

All told Aung San Suu Kyi’s government signed up for infrastructure deals with China that added up to over $ 20 billion by the spring of 2020. By 2023 the figure may have risen to as much as $35 billion. Chinese money dwarfs all potential rivals, notably India which has offered investment totalling a few hundred million dollars.

With Aung San Suu Kyi as a partner, Beijing found itself in the unwonted position of being able to push forward its BRI agenda hand in hand with a highly popular democratic politician. The coup in Feb 2021 put Suu Kyi under house arrest and triggered insurgencies against the central government. Nevertheless, Beijing has persisted, hoping that it can bring the Junta under its sway.

As the Economist remarked there are not just long-run strategic interests at stake for China in Myanmar. There are also issues of more immediate concern:

The fortunes of Yunnan, the poor Chinese province adjacent to Myanmar, hinge on stability on the other side of the border. Chinese investors flocked across because they see Myanmar as a portal to South-East Asian economies. Oil flowing through a pipeline from Myanmar supplies a refinery that contributes 8% of the province’s gdp. …. At the terminus of the pipeline, on Myanmar’s western coast, China is bankrolling the construction of a deep-sea port which, once completed, will enable it to import oil and gas via the Bay of Bengal.

Even as Myanmar’s junta murdered its own population, China provided it with arms to the tune of $250m last year.

But China too is frustrated by the lack of stabilization in Myanmar, most notably in the border regions where organized crime spills over into China. It is an open secret that China’s secret services and military are backing not just the Junta but also have their hands in the 1027 offensive, which has brought much of the border region under the control of ethnic armies armed and controlled by China. The so-called Three Brotherhood Alliance that has carried the 1027 campaign has close links to China’s security services. As one agency reports:

Tellingly, the Brotherhood Alliance announced that one of its goals was to eliminate a network of online scam operations that over the past three years has sprung up along the Myanmar-China border. A major security concern of China’s, these operations are estimated to be behind the trafficking of 120,000 unsuspecting workers to Myanmar, many of them Chinese, and to generate billions of dollars a year in revenue, much of it fleeced from Chinese victims.

For the Junta this Chinese pivot towards the opposition no doubt came as a painful shock. But it did not surrender to Beijing. Its first response was to unleash anti-China mobs in several major cities. Beijing in turn made a public show of support for the junta, by conducting joint naval exercises and hosting a meeting between China’s top diplomat, Wang Yi, and Myanmar’s deputy prime minister, Than Swe, in Beijing. Then, on December 14th China announced that it had brokered a temporary ceasefire between the army and the ethnic militias.

What is the logic of this complicated and violent maneuvering? The answer given by Priscilla A. Clapp; Jason Tower of the USIP is that China is involved in an elaborate strategy of containing the damage done by the junta, whilst at the same time splitting the resistance to it by bringing different factions under Chinese influence and then brokering piecemeal ceasefires. As they write:

China’s longer-term strategy is undoubtedly designed to fragment the anti-junta resistance by helping individual armed groups achieve victories over limited territories in the border area in exchange for abandoning ambitions to participate in coalitions aimed at regime change. Over the medium term, China may consider this as a lifeline for the Myanmar army to keep itself in power, as well as a means of assuring dependence on China for all parties to the conflict and ultimately maximizing Chinese influence in Myanmar. However, a strategy of this kind is unlikely to be sustainable over the longer term because it is a recipe for even greater levels of instability across Myanmar. First, it fails to recognize that the Myanmar army has become completely illegitimate in the eyes of the Myanmar people. By pushing Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) to sign deals with the Myanmar army, China risks provoking serious and sustained anti-China sentiment, which could imperil the security of Chinese strategic investments in Myanmar. Second, making EAOs partner with the Myanmar army would threaten their legitimacy with the public, causing them to lose the popular mandate essential to stable governance. In the end, such a strategy could prove self-defeating.

In conclusion, it would be facile to suggest strong analogies between the shatter zone of the Middle East and in South East Asia. But what is clear is that both regions are feeling the effects of shifting patterns of global geopolitics. In both arenas the influence of Western power, money and political persuasion is declining fast, dramatically relativized by the willingness of other players (notably Russia) to chance their hand, and the emergence of China as a dominant source of money, political backing and military support.

***

Putting out Chartbook is a rewarding project. I am delighted that it goes out free to tens of thousands of subscribers all over the world. What makes the project viable are the contributions of reader like you. If you are not yet a subscriber but would like to join the supporters club, click here:

You might also wish to comment on the resumption of genocidal violence and ethnic cleansing in southern Sudan perpetrated against the Masalit, Black Africans, by Arab Muslim Sudanese. It doesn't fit the intersectional narrative, but is, in fact, a colonialist outrage against an indigenous people. Except in this case the colonizers are Arab Muslims out to grab oil, gold minerals, and land. Can we expect a 100,000 person turnout in London or outrage on US university campuses? Any X posts from BLM? Not likely.

Thank you for an excellent review of the area!