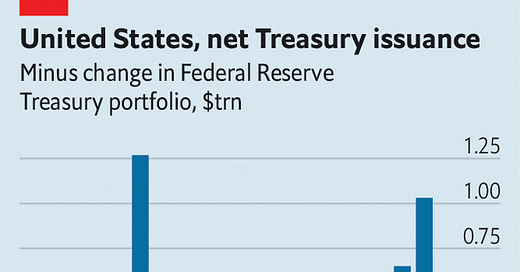

The US Treasury market is by some margin the most important financial market in the world. Outstanding US debt creates underlying claims to the tune of $26.6 trillion, up from $12.2 trillion ten years ago. From October 2022 to 2023 the US Treasury on net, issued $2.2trn in bills and bonds, worth 8% of gdp. That funded a large US deficit. It also created private claims to that same amount, offering attractive possibilities for investment.

Source: Economist

It is also fragile. In 2014, in 2019 in 2020 and in 2023 it displayed worrying and at times truly critical levels of instability. Oddly, when this happens officialdom likes to talk of the Treasury market experiencing “jitters”. Most recently Gary Gensler chair of SEC gave a speech in which he catalogued “jitters” going back to the 1980s.

Jitters is an oddly understated phrase to describe a shock that in the judgement of most experts has the potential to do more damage to global finance than any other.

It brings to mind the slighter symptoms of alcoholism, first night nerves, or a slightly manic dance craze of the 1940s.

Perhaps this understate phrase - jitters - is chosen because the symptoms of a crisis are fluctuations in prices that resemble spasmodic bodily movements. That was the main issue in 2023. There was remarkable volatility in the prices of assets that are normally treated as the rock-solid foundation of the financial system.

One of the really big worries is that these “jitters” might self-amplify, leading to structural failure and collapse. In particular there is a worry that there might be a toxic loop between volatility and liquidity, in which sudden swings in prices lead major players in the Treasury market to withdraw from trading (algorithms may play a role here) or, even worse, to self-protective behavior by lenders (margin calls), which tighten credit and force Treasury speculators to offload their holdings. Either pressure would reduce liquidity, which in turn narrows the market and makes it more likely that prices swing erratically, amplifying the pressures to withdraw from trading, or to make margin calls and trigger fire sales.

The evidence that any of this actually happens is complex and has been vigorously debated by highly expert and highly incentivized market actors, regulators and Treasury officials ever since the last really world historic “jitter”, in March 2020.

As the Economist notes, there is no consensus within the government machine:

In a sign of diverging opinions between the sec and the Treasury, Nellie Liang, an undersecretary at the department, recently suggested that the market may not be functioning as badly as is commonly believed, and that its flaws may reflect difficult circumstances rather than structural problems. After all, market liquidity and rate volatility feed into each other. Thin liquidity often fosters greater volatility, because even a small trade can move prices—and high volatility also causes liquidity to drop, as it becomes riskier to make markets. Ms Liang pointed out that “high volatility has affected market liquidity conditions, as is typically the case”, but it does not appear that low liquidity has been amplifying volatility.

The question is hard to decide because we don’t know all that we might about how the Treasury market and its working. Regulators want to change this by requiring more traders in the market to register as primary dealers who are subject to tough reporting requirements. Hedge funds would prefer not to have to disclose this information.

Regulators are particularly worried about a speculative trade much practiced by hedge funds known as a “basis trade”. They worry about it because it is such a small margin trade that it is only profitable with huge leverage i.e. if the hedge fund can employ a minimum of its own money and a maximum of borrowed funds. According to one set of estimates in December 2022 the hedge funds owed $553bn on basis trade borrowing and were leveraged at a ratio of 56 to 1. This creates the potential either for widespread losses in the credit system or major hedge fund failure. As the Economist reports:

Loans to hedge funds do not much threaten banks, which have the security of the bond if they are not paid back. Instead the chief worry is that a failure of a large hedge fund could set off a repeat of the “dash for cash” at the start of the covid-19 pandemic, in which investors dumped Treasuries; or the doom loop that struck Britain’s bond market in September 2022, in which falling bond prices forced pension funds to sell bonds, further pushing down prices. These fire sales were resolved only when central bankers bought bonds at scale.

The hedge funds themselves insist that it is their activity which creates a deep and liquid market without which Treasuries would not have the foundational function that they do which in turn makes it cheaper for the US tax payer to borrow. Their speculation serves as public purpose. And as the Economist magazine points out, they can cite no lesser authority than Alexander Hamilton to back them up.

So one can tell the story of the US Treasury market as one in which highly leveraged and incentivized actors dance on the edge of a precipice of financial disaster, debating the finer points of repo market regulation and reporting. Regulators, central bankers and Treasury officials politely edge around their relations with key banks, like JP Morgan and hedge funds like Citadel. And some folks make a lot of money engaging in opaque financial engineering, constantly probing the boundaries of liquidity and volatility.

That would be a bit of a dirty secret. Enough to make your knee twitch or your fingers tap.

One could also say, however, that the real secret of this entire Treasury market debate is that it is an artifice. A complicated elaboration of public and private financial entanglement that we have chosen to erect. Because, as everyone knows, if the private wheeler-dealing in public debt ever really breaks down. If the desperate desire for liquidity - a so-called “dash for cash” - can no longer be met in private markets, there is always a perfectly good answer that was there all along. All that needs to happen is for the central bank, the limitless provider of liquidity (unless constrained by self-imposed legal rules as in the case of the ECB), to step in and to buy up the Treasuries for cash. That is what the Fed and all the other central banks did in March 2020. It was what the Bank of England was reluctantly forced to do in the UK during the gilt market crisis of September 2022. And what happens then? Nothing! The financial market crisis ends. The system is flush with cash which the central bank could have issued all along. What about the Treasuries? The public ends up owing them to itself. The publicly owned central bank has a claim on the Treasury and the tax-payer.

This is the core truth of all sensible thinking about public finance going back to Keynes, Abba Lerner and from them forward to MMT’s teaching about public borrowing: “we owe it to ourselves”. The decision to engage in public debt issuance is a choice. A choice to create a private market for public debt, to turn public liabilities into private assets, to build a financial system on that, to manage it through Treasury markets, repo facilities etc. If it fails, it can in extremis be reabsorbed into the closed loop of the Treasury and the central bank, whose relationship is not that of a private bank to a private borrower, unless we chose to structure it that way.

What are the risks entailed by this? Again the Economist is frank and illuminating:

Fire sales caused by financial rather than fundamental factors in effect result in the central bank buying back government bonds on the cheap. The Bank of England made a £3.8bn ($4.8bn) profit on its purchases, a return of 20% in a matter of months. … Provided central banks get in and out of the market quickly … there is nothing untoward about stopping fire sales of sovereign debt. Indeed, knowing central bankers can act should create a more liquid market, which will help keep bond yields low and well-behaved. … The trouble comes when central banks fail to contain the panic or stay in the market long after it has stabilised. After the dash for cash, central banks’ goals switched from financial stability to monetary stimulus. They amassed huge portfolios of long-term bonds which have fallen in value as interest rates have risen. At the end of September the Fed’s mark-to-market losses on its portfolio of Treasuries stood at nearly $800bn. Ultimately, these losses pass through to the Treasury.

So the complications of the Treasury market are complications that emerge from history - the shock of fund-raising during major wars - and political economy - the powerful financial interest and its allies within the state structure and the political system, and are then ramified by the network effects of highly incentivized, complex and sometime efficient private trading. On this, check out Chartbook 238 on Menand and Younger and the history of the US Treasury Market. When that system suffers a heart flutter, the interventions themselves can tigger new historical processes, which include a ratcheting upwards extension of central bank intervention.

What Gary Gensler is proposing fits squarely within this logic. Not of massive central bank purchases but of preemptive organization and illumination of what is going on in the market.

As the Robin Wigglesworth of FT’s alphaville comments on Gensler’s speech:.

The four main reforms that Gensler is focusing on to stiffen the sinews of the US government bond market. …

First, following the 1986 Government Securities Act, rules were put in place to register government securities dealers. In the ensuing decades, numerous firms have registered with the SEC, but some market participants acting in a manner consistent with dealers have not. To fill this regulatory gap, the SEC proposed rules that would further define a dealer and a government securities dealer. Market participants acting as de facto market makers in the business of providing liquidity in Treasuries or other securities would register with the SEC and comply with securities laws. When dealers or government securities dealers register, they become subject to a variety of important laws and rules that help protect the public, promote market integrity, and facilitate capital formation. This is one of the things that Ken (Griffin of Citadel Hedge Fund) is so upset about. The issue is that there isn’t really a clear delineation between liquidity provider or taker, so it would subject a lot of “market participants” to the same kind of onerous controls that primary dealers face. We can see why that’s annoying, but it also seems like it’s an entirely fair way of leveling the playing field.

Registration of Trading Platforms

Second, the Commission proposed rules to require platforms that provide marketplaces for Treasuries to register as broker-dealers and comply with Regulation ATS….This update would close a regulatory gap among platforms that act like exchanges but are not being regulated like exchanges.

Central Clearing

Third is our proposed rule to enhance central clearing.[18] This is not a new topic. In fact, a 1969 Joint Treasury-Federal Reserve Study of the U.S. Government Securities Markets included a recommendation that: “Consideration should be sought in expanding clearing arrangements for U.S. Government securities.”[19] Clearinghouses came to the Treasury markets in 1986. By 2017, however, only 13 percent of Treasury cash transactions were fully centrally cleared. … Reduced clearing increases system-wide risk. …

Data Collection

Fourth, let me turn to data collection. After the 2008 crisis, Congress recognized it was important to have more transparency regarding private funds. In 2011, along with the CFTC, we adopted rules on data collection from private funds, what’s known as Form PF. Ever since, Treasury, OFR, and the FSOC have had a better understanding of these markets. Yet private funds have evolved significantly in the last 12 years. In May, the SEC finalized a rule requiring, for the first time, that large hedge fund and private equity fund advisers make current reports on certain events to the Commission.[23] We also have a joint proposal with the CFTC regarding Form PF updates, which would greatly enhance the view of the Commissions and FSOC into private funds’ leverage as well as provide a clearer picture of counterparties. … This will bring more data into the Trade Reporting and Compliance Engine (TRACE). I also am pleased by Treasury and FINRA’s ongoing efforts to enhance post-trade transparency in the Treasury markets, which the SEC is reviewing.[27]

This, as Wigglesworth notes, is another reform that Citadel and most of the hedge fund industry hates. “Again, transparency isn’t actually costless … but it’s hard to see strong arguments against regulators getting more insight here (even though FTAV is sceptical it will help much). So, full steam ahead Gary!”

The key point here is surely that when it comes to US Treasuries, the most important financial market in the world, any notion of the naturalness of markets simply evaporates. The entire edifice is precisely that, a socially, legally, economically and politically constructed edifice from top to bottom. It reflects outside forces of course - like inflation, or a huge surge in new debt issuance - but it jitters not the way that a building shakes in an earthquake, but the way reputations tremor in a social media system, or our minds jitter in an emotional storm. It is fully internal to the system of politics, law and economics of which it is an artifice.

***

Putting out Chartbook is a rewarding project. I am delighted that it goes out free to tens of thousands of subscribers all over the world. What makes the project viable are the contributions of reader like you. If you are not yet a subscriber but would like to join the supporters club, click here:

"The key point here is surely that when it comes to US Treasuries, the most important financial market in the world, any notion of the naturalness of markets simply evaporates. The entire edifice is precisely that, a socially, legally, economically and politically constructed edifice from top to bottom.

It is fully internal to the system of politics, law and economics of which it is an artifice."

Wherein Tooze says more succinctly and elegantly what I have been railing about (often with a searing vulgarity which reflects my rage at the duplicity and stupidity on display in the public discourse) for years now -- the whole notion that this is remotely what normal people understand a market to be, along with the premise that this is anything like private enterprise, IS A FUCKING SHAM!!

According to neoclassicists and vulgar mainstream economics credit money - or debt is not a factor in macroeconomics - it is just redistribution. Almost all Neoclassical macroeconomic models entirely omit the existence of banks, private debt and money. Even when they do consider private debt, they assert that only the distribution of debt matters, and not its absolute magnitude. Nobel prize winner Bernanke, argued that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution between groups from debtors to creditors, reflecting both sides of the balance sheet. Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups pure redistributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects.

There are more contradictions in the post - “Ultimately, these losses pass through to the Treasury”, which at the end of the day is the public. Yet Tooze states in another paragraph “it can in extremis be reabsorbed into the closed loop of the Treasury and the central bank, whose relationship is not that of a private bank to a private borrower”. It is his usual hyypocritical way of beating around the bush - we the public, we are in fact the private borrowers left holding the bag when things go awry, after the elites have been making huge gains out of these finance games with fictitious capital. The game by financial elites and their governmental henchman is kicking the can further down the road by running up endless debt for upward wealth redistribution