“Crazy Rich Germans”? … it doesn’t ring quite right, does it. Surely, Germany is a well-groomed social market economy? No badly behaved, high-spending crazy-rich people there.

You can make entire movies driven by clichés about the Asian nouveau riche. The wealth of Arab sheikhs is legendary. Europe has dined out for more than a century on gossip about the antics of America’s billionaires. Piketty’s famous inequality studies updated that trans-Atlantic trope for the 21st century. But what about Europe’s own ultra wealthy?

Obviously, there are plenty of people on the old continent with loads of money. It is not for nothing that Europe is home to so many of the world’s high-end luxury brands. British aristos still own huge slices of the country. Russian oligarchs boast some of the biggest yachts in the world. Paris is a city of extreme wealth and exquisite luxury, as is plain for any visitor to see. Places like Luxembourg, or Zurich or Geneva glitter with affluence. But what about Germany, the mightiest economy in Europe?

Germany is a society, like any other based on capitalism, characterized by huge inequality. Not for nothing, it is the home of one Europe’s oldest socialist movements. Germany gave birth to social democracy before it did to social market economy. Germany was once a place in which the barons of industry, commerce and banking were notorious for cozying up to the Kaiser and “paying for” Hitler. After 1945 Germany’s industrialists were put on trial at Nuremberg for their involvement with the Nazi regime. Today, some of Germany’s biggest and most successful businesses are still privately held - think BMW or the Aldi chains. It is clear that there are some very, very rich people in Germany - multi-multi-billionaires. But who they are and how much they are worth is a harder question to answer. If there is one thing that is distinctive about Germany’s ultra-wealthy it is how discreet they are. There is no equivalent in German public life of Elon Musk, or Bill Gates or Bernard Arnault. In public, the rich stay out of the limelight and allowing Germany to celebrate itself as a harmonious social market economy.

It helps in maintaining this myth that there is no official register of wealth. The annual national report on Poverty and Wealth does not dig deep into the situation of the super-wealthy. It defines anyone as “rich” who has a net income of more than 4.200 Euro per month, an income from capital of more than 5000 euros per year or a personal net worth of more than 500.000 Euro. This defines almost 10 percent of the population as “rich”. This level of privilege is important. But it does not capture the power relations and influence conferred by real wealth.

The Bundesbank tracks wealth inequality as part of its macreconomic monitoring regime, but it also does so at a very high level of aggregation.

When it comes to monitoring elite wealth, the sources are much scarcer. Forbes magazine counted 117 individual German billionaires in 2023. But since large wealth is organized in family holdings, it is more meaningful, as Germany’s Manager Magazine does, to count billion-euro “fortunes” (Vermoegen). The Magazine in 2023 counted 226 such fortunes. The list, however, is clearly incomplete. And the magazine has acknowledged that it has been subject to behind the scenes legal pressure to omit several notable families.

We know this startling fact thanks to a new surge of public interests in inequality in Germany. German activists are beginning to flex their muscles and unlock the power of expose and muck-raking. Websites like ungleichheit.info do a great job telling the dramatic story of inequality.

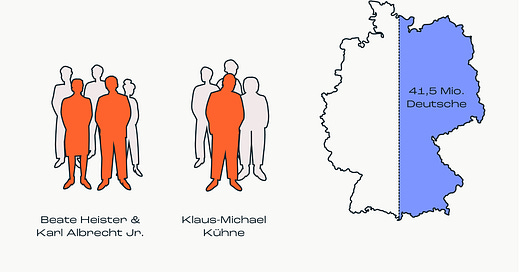

The two richest German families own more wealth than the bottom half of the German population

Source: Ungleichheit.info

This week researchers from German Tax Justice network (Netwerk Steuergerechtigkeit), Julia Jirmann and Christoph Trautvetter, released a remarkable technical report reestimating German billionaire wealth. It has been picked up by TV documentarians and inequality researchers Julia Friedrichs and Jochen Breyer, as the backbone of a hard-hitting ZDF expose. You may be able to access it (in German) here.

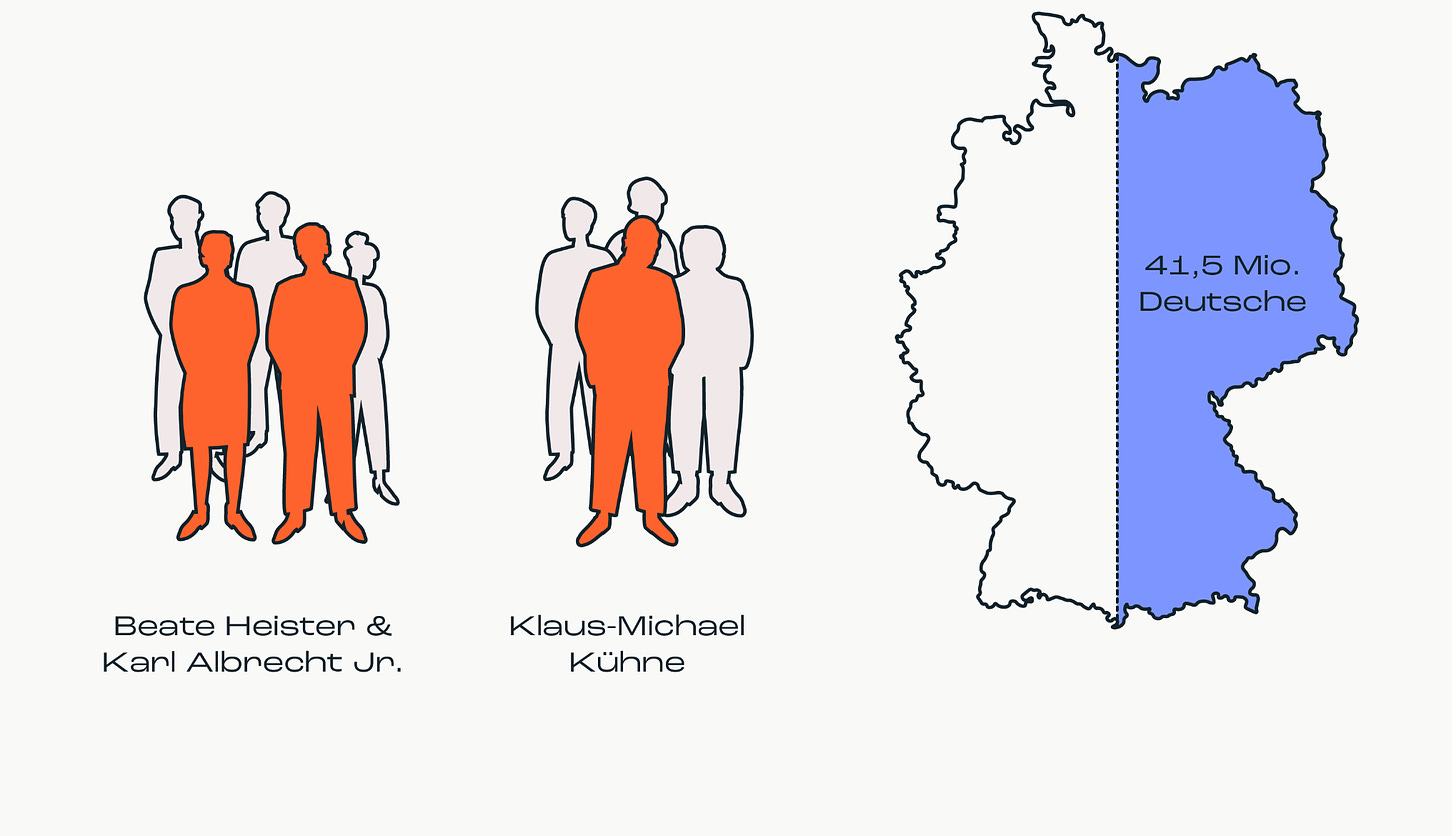

The unprecedentedly comprehensive investigations by Jirmann and Trautvetter have added 11 fortunes to the Manager list, for a total of 237 billionaire family fortunes in Germany. More significantly they have raised the estimate of their total wealth from the 900 billion previously identified by Manager Magazine to somewhere between 1.4 and 2 trillion euros. You can download the excel spreadsheet here.

Missing billion-euro fortunes hitherto unreported in the Manager Magazine list include:

As the researchers show, Forbes magazine generally reaches higher estimates of wealth than their German counterparts at Manager Magazine and so adjustments are warranted. Also wealth accounting struggles to fully capture non-distributed profits.

One thing is clear. German billionaire wealth is huge and underreported. And a large part of it is no longer connected to direct family ownership of businesses. Debunking the claimed connection to family entrepreneurship is key to delegitimizing extreme.

Germany’s wealthiest families may be discreet, but this does not prevent them from engaging in powerful lobbying activity through a network of foundations led by the Stiftung Familienunternehmen (Foundation for Family-owned Firms), Die Familienunternehmer e. V. and the Initiative Neue Soziale Marktwirtschaft (INSM). These groups assiduously promote the idea of family ownership of property on behalf of the core group of super-wealthy, who in fact represent 0,00017 percent of the 3 million small family-owned businesses in Germany.

In reality 18 percent of the largest fortune in Germany no longer have any connection to a specific firm. Only just slightly more than half of “family-owned” large firms are actually led by a family member. In less than 10 percent of those firms is a woman in a leading position and there is only one East German family-owned firm in this elite group of german capitalism.

The German wealth lobby pushes hard for policies that serve their interests. And despite the rhetoric about a social market economy they have succeeded in changing the tax system to the disfavor of the vast majority of the German population.

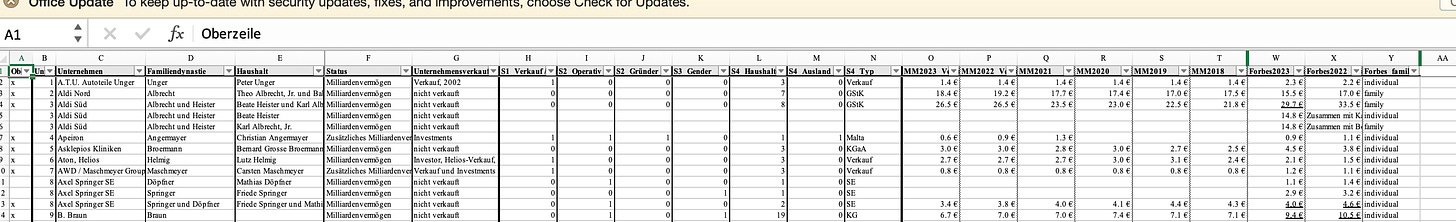

Germany’s wealth tax was suspended in 1997. Corporation tax was cut in 2001 and 2008 and further loopholes were added. Germany’s peak income tax rate was repeatedly cut in the early 2000s and additional benefits were introduced for saved dividends. In addition Germany’s wealthy received expert legal and accounting advice to manipulate the system to their advantage. The net result is that as elsewhere Germany’s extremely rich families pay hardly any tax on the income they derive from their immense wealth.

A very nice compilation of benefits exploited by a typical wealthy family in Germany was put together by Jirmann and Trautvettter

And tax is only one of the facets of public life they influence. You might think that German democratic politics with its publicly funded political parties would be relatively immune to the influence of great wealth. Or at least less sensitive to the interests of the wealthy than the democratic system in the USA where politicians can be openly bought. But as work by Lea Elsässer, Svenja Hense and Armin Schäfer has shown, German democratic politics is, if anything even more sensitive to the preferences of the best off and less responsive to the preferences of the poorest, than the system in the USA.

In this paper, we have shown that policy responsiveness in Germany is also biased towards the better-off as it is in the United States. Lower social classes see their preferences reflected in political decisions less often than higher social classes, in particular when it comes to highly contested issues. In order to facilitate the comparison with findings for the US, we replicated the research design that others have used as far as possible. Our original dataset includes 842 questions that ask about agreement or disagreement with specific policy proposals and were posed between 1980 and 2013. We calculated the degree of support for both income and occupational groups and added information on whether or not the German Parliament decided to implement the policy within four years. Our findings show, overall, that the Bundestag’s decisions are responsive towards the better off but virtually ignore the preferences of the poor. When it comes to questions the rich and poor disagree on, the effect of support by lower-income groups on the probability of enactment even turns negative. The more these groups favor a certain policy, the less likely it is to become law.

Privilege and political influence thus form a self-reinforcing loop that is hard to shake loose. According to the historical data compiled by Albers, Bartels and Schularick the only period in which the structure of German wealth inequality was shaken loose was the “transwar” period of 1914 to 1945. The history of the Federal Republic of Germany and its fabled social market economy has been marked by stabilization and then a gradual increase in wealth inequality.

Since the early 1990s Germany has seen a highly unbalance surge in top-1-percent wealth.

The net result, by the second decade of the 21st century, was stark. Germany’s ueber-rich elite have every reason to draw a veil of discretion over their activities.

Source: IW Koeln

As data from the IW research center in Cologne confirm, Germany’s social market economy, like the social democracies of Scandinavia, earns its sobriquet of “social” by providing a significant amount of income equalization (vertical axis above). But that redistributive side, shields an underlying wealth inequality, which is massive (horizontal axis). If the data are to be believed, German wealth-holding by the 2010s was more concentrated than in any other large European society. In terms of their wealth-ginis France and Italy are closer to former communist Czechia than they are to Germany. In terms of gini coefficient, Germany’s wealth inequality at 0.79 is closer to that of the USA (wealth gini 0.81-0.86), than to countries you might think of as being its European peers.

Germany may gloss itself as a social market economy. In terms of income redistribution that claims is real. But underlying that political model, is a society that truly deserves the label of a “capitalist democracy”.

Capitalism and democracy make for a tense pairing. And the stakes of progressive politics must surely be to raise the tension in that relationship. Public opinion in Germany, as elsewhere, is increasingly convinced that the benefits of modern society are too unequally distributed. Rather than decrying these views as populist, or denouncing them as “social envy”, progressive politics should surely aim to organize that dissatisfaction and to arm it with arguments and data.

In the fight over inequality, one essential prerequisite is publicity. Research shows that in Europe, unlike in the US, giving voters information about inequality intensifies their preference for redistribution. As Julia Jirmann and Christoph Trautvetter of the German Tax Justice Network comment, what the German public lacks is adequate information about the basic structure of their own society.

The wealth of Germany’s billionaire fortunes is divided across only 4300 separate households. If regular analysis was extended to the top 1000 fortunes and their business and property empires, it would require monitoring the finances of roughly 0,1 percent of the population or 40,000 households. Is this too hard a task for a sophisticated state apparatus like that of Germany? Or would it simply be too embarrassing to reveal how little contribution this vast wealth makes to the public finances.

A 2 percent tax on wealth - to start with a modest proposal - would generate substantial revenue. It would ensure, if it were properly enforced, that the wealthiest pay approximately the same rate of tax on their capital income as the rest of society on its income from labour. It would slow the growth of further polarization. And It would force the issue of wealth inequality into public discussion. It would place wealth and the income it generates alongside taxes on labour and social spending which are so often made the focus of demands for retrenchment and austerity. At a time of (self-inflicted) budgetary crisis, it should surely be on the table.

TL:DR: now that communism is no longer a threat, the ruling classes in Europe no longer see any reason to toss a few crumbs to the masses.

As someone living in Germany, this makes for particularly fascinating reading.

Slightly different topic but I'd be curious to know what research there is on social mobility within German society. How does it compare to other countries? My hunch is that socioeconomic mobility is actually higher here compared with the US, for instance, despite the 'American Dream'.