After a decade of miserable growth, the shock of Brexit, the miserable mismanagement of the pandemic and the ongoing shambles of Tory misrule, the future of the UK economy is in question. If one can still speak of a British growth model - David Edgerton might question this assumption - that model is broken.

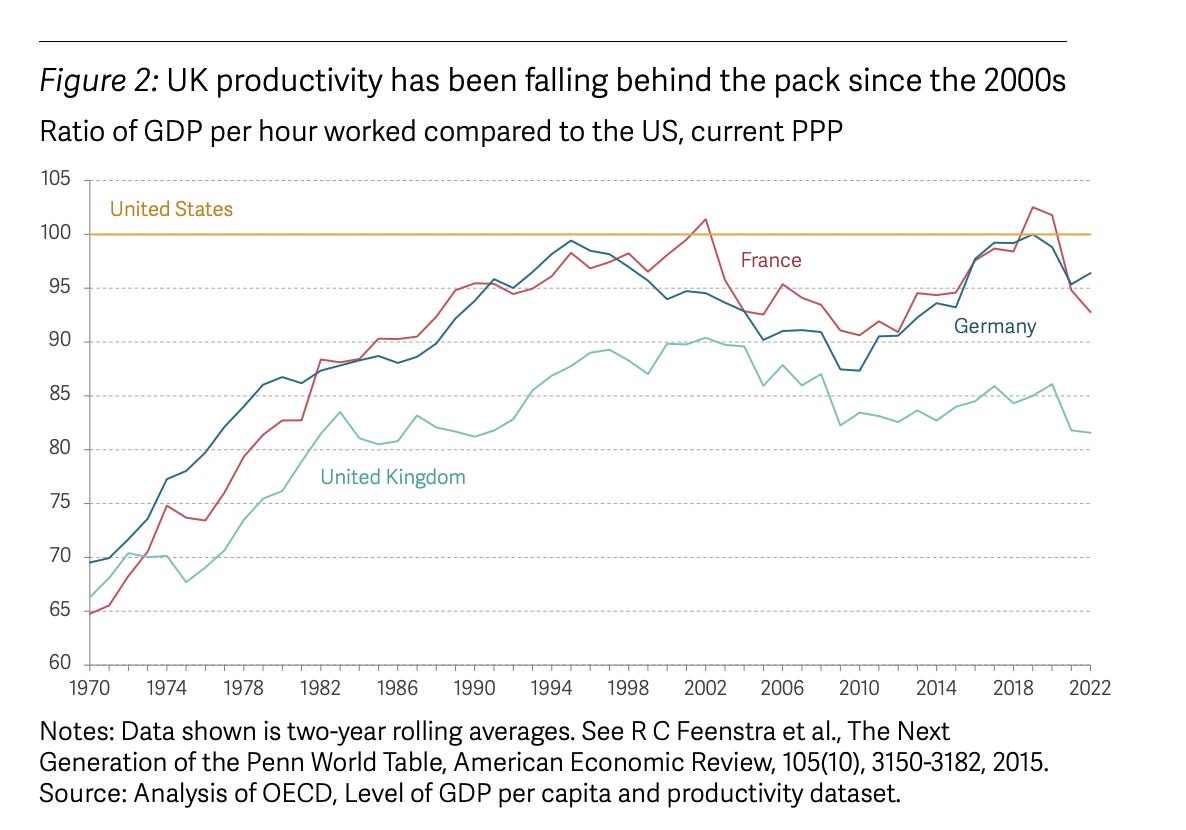

Unlike in the US, the problem in the UK is not that wage growth has become uncoupled from productivity growth. Wages and productivity in the UK remain linked. The problem is that productivity growth has stalled.

Britain’s productive stagnation is not yet as serious as that in Italy. But then Britain is not in the eurozone and a flexible exchange rate ought to have given it the possibility of more rapid growth.

If we compare the UK not to Italy, but to the more high-performing European economies and the US, deconvergence amounts to c. 20 percent. The break came not with Brexit but in 2008/9 under New Labour, with the financial crisis. If real wage growth in Britain had continued on the pre-crisis trend, earnings would now be almost 40 percent higher than their current level. As things stand, real average weekly earnings in 2023 are below their 2008 peak, a stagnation that is unprecedented in Britain’s modern history. When it comes to things like inflation, British commentators like to draw anxious comparisons to the 1970s. As far as productivity is concerned, such comparisons are unfair to the 1970s.

This national economic disaster has sparked a number of searching enquiries into the state of Britain. On Twitter there is talk of a “Great Noticing” as even the last Brexit-addled Tories wake up to the seriousness of the situation.

I had the privilege of serving as a Commissioner on the Economy 2030 Inquiry, an extensive research project headed by the Resolution Foundation and staffed by researchers at the CEPR and LSE amongst others.

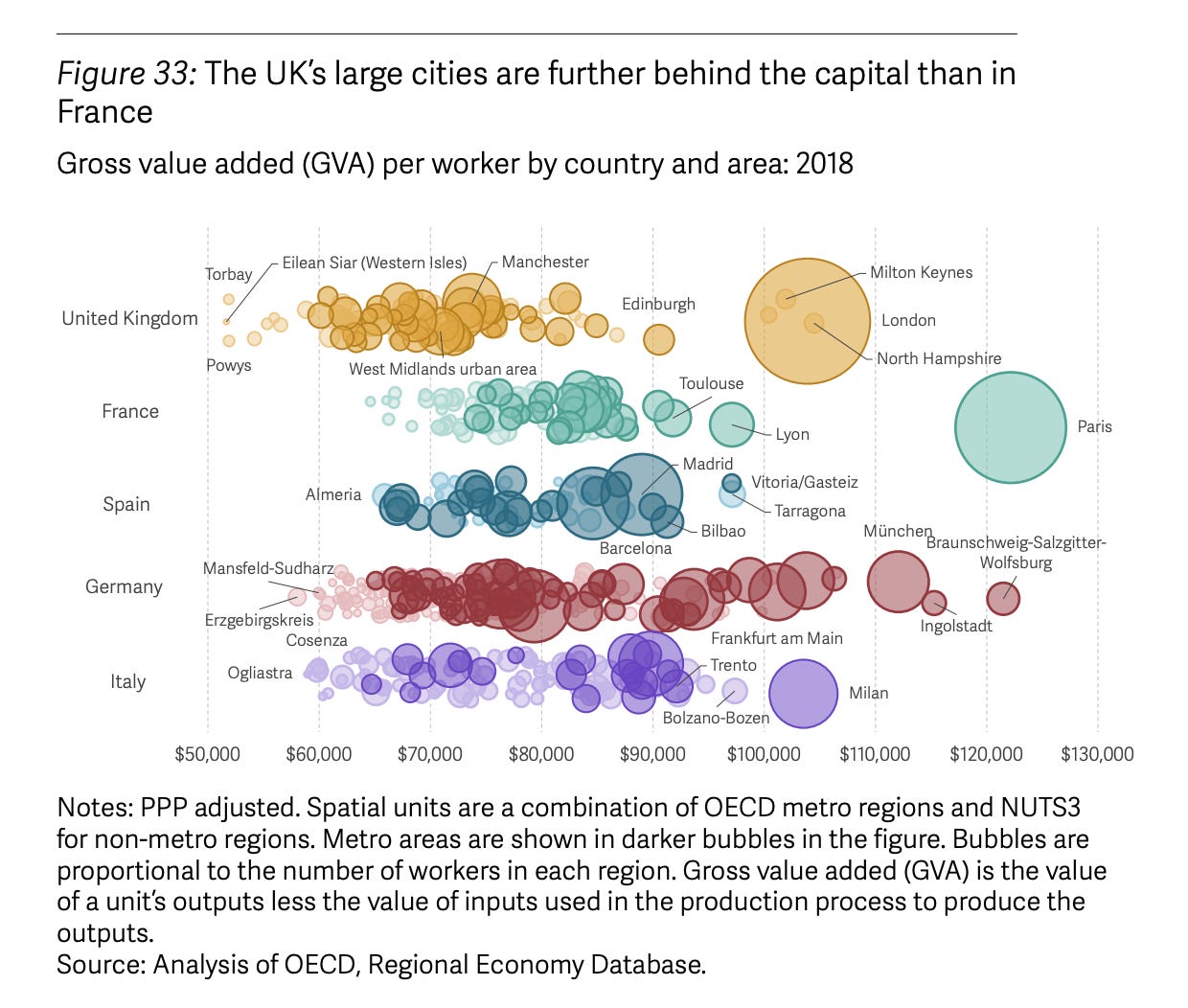

One of the issues highlighted by the Inquiry is national divergence: the huge gap that yawns between London, the South East and the rest of Britain.

London boasts world-class productivity and incomes to match. Much of the rest of Britain does not. There is a strikingly large gap between London and Britain’s second cities, Birmingham and Manchester. This is larger than the equivalent gap in France between Paris and a city like Lille. As the report comments:

Greater Manchester and Birmingham. With populations of around 2.8 million each, both easily rank among the biggest 30 cities in Europe. Yet Birmingham is 14 per cent less productive than the UK overall, and has an employment rate 5 per cent below the national average, while even Greater Manchester, widely regarded as an economic success story, has productivity 12 per cent below the UK average.51

As to the underlying causes, though there is a lot of talk in Britain about a surfeit of education, in fact Britain suffers from a lack of human capital, especially in middle and lower skilled occupations.

Human capital formation is not encouraged by the fact that wages are low and the premium commanded by graduates everywhere outside London has fallen, signalling that the local economy cannot make particularly good use of high-skilled labour.

Put another way, highly skilled workers who might prefer to make lives for themselves and their families outside the hot spots of London and the South East, face an increasing penalty for making that choice. Rather than convergence this will tend to drive deconvergence within Britain itself.

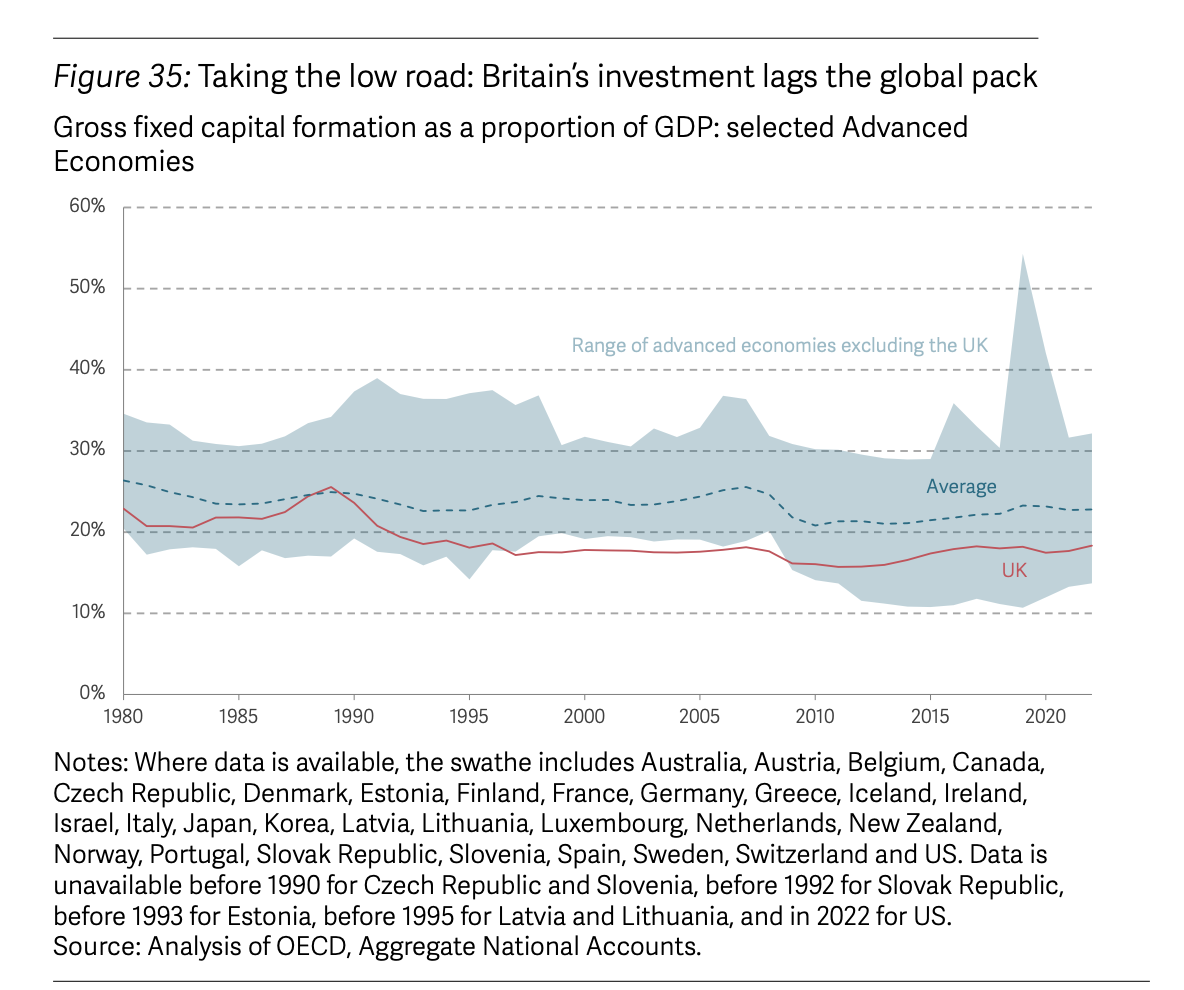

If we ask why labour productivity is not higher, the obvious culprit is inadequate investment. Overall the British economy has long lived with low rates of investment in both the public and private sectors. So this factor will not by itself explain the emergence of stagnation since 2008. But it compounds all of Britain’s other problems. At some point the chickens come home to roost.

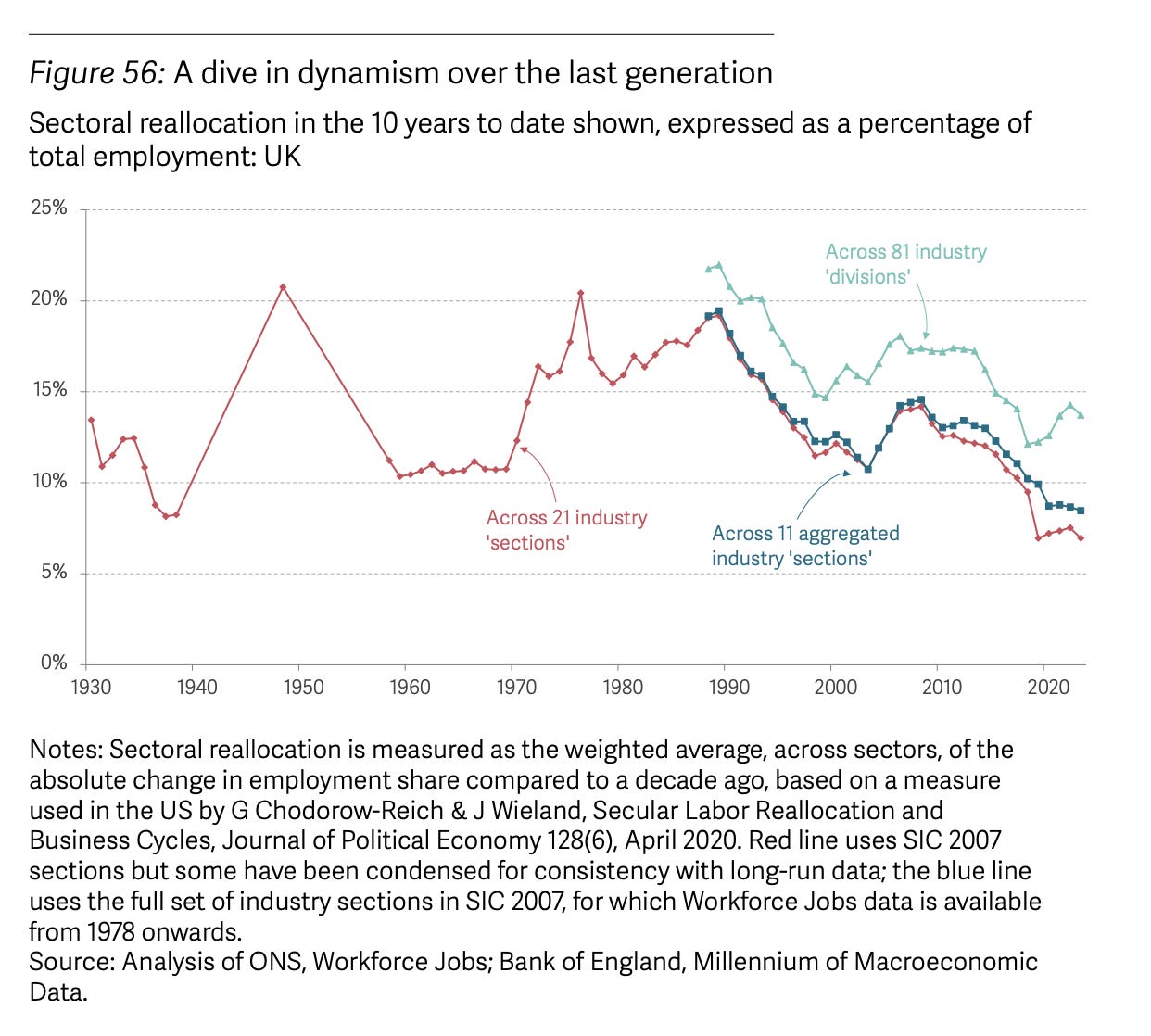

Unsurprisingly given this low rate of investment, the UK has recently experienced a declining rate of structural change.

To put capital and labour to work productively requires good management. And though there are many British firms which are well run, the UK has a long tail of underperformance.

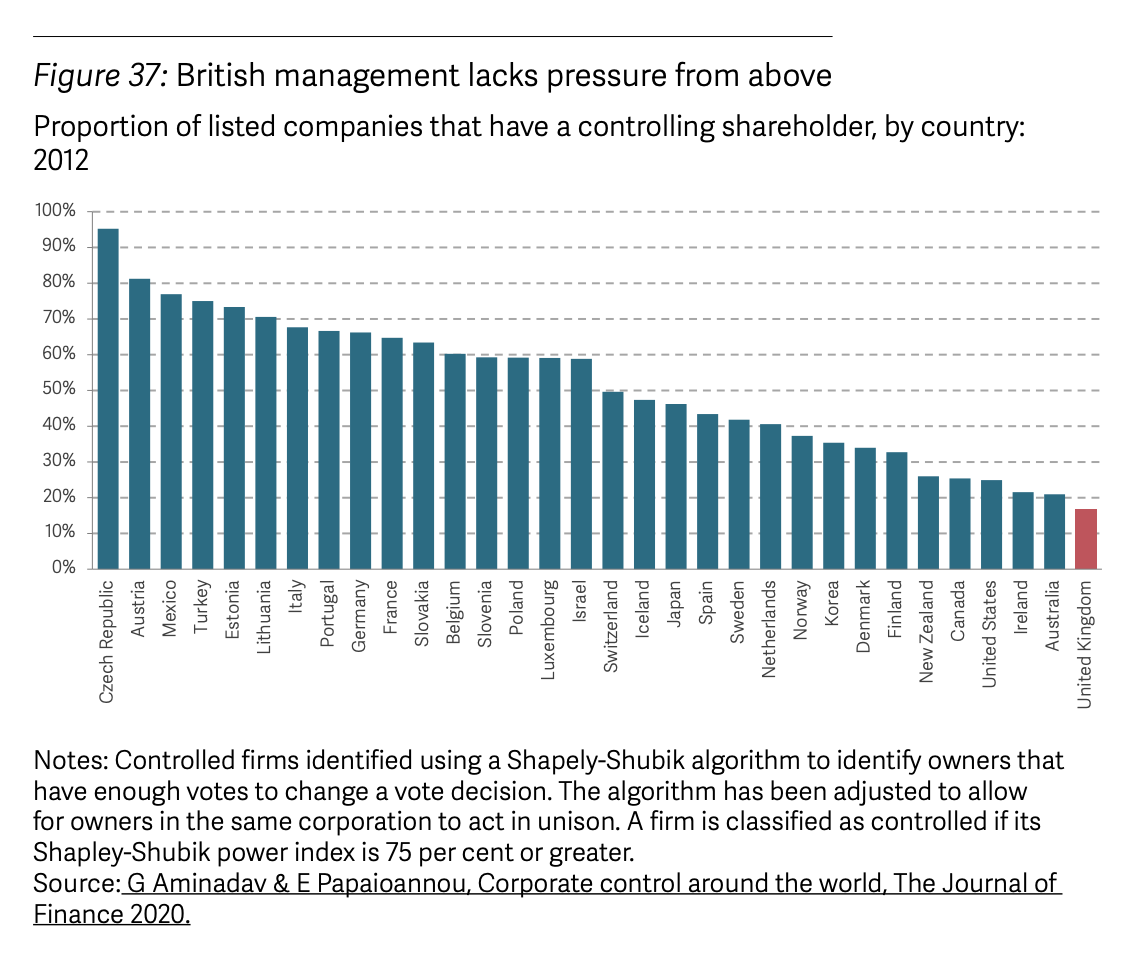

Assuming that owners are in general interested in maximizing returns, a long tail points to weak structures of corporate governance. What is particularly striking in the UK case is the extent of foreign ownership - foreign ownership of UK public firms rose from just over 10 per cent in 1990 to over 55 per cent in 2020 - and the extent to which firms lack a single controlling share owners, who would be in a position to oversee management strategy and reap the full rewards of success.

Furthermore, as the report notes it is not just not capital that is poorly represented in corporate Britain:

The UK stands out even more internationally when we recognise that the lack of ‘owner voice’ is matched by a lack of worker voice, so that pressure from below for managers to invest for the long term is unable to compensate for the lack of such pressure from above.

This strongly supports David Edgerton’s contention that to speak of a British economic model is to miss the point. Corporate Britain isn’t very British and it lacks a model. Insofar as anyone has agency it would seem to be a largely unconstrained managerial class, who to judge by the data are doing a thoroughly mediocre job.

Given this state of affairs it is easy for those owning firms operating in Britain to imagine reallocating investment and work away from Britain. The negative consequences of the gratuitous self-amputation of Brexit fall particularly on the highest productivity sectors.

What does the Inquiry report recommend by way of solutions?

Raising investment and skill provision are the most obvious requirements. Britain has failed to achieve those objectives for decades but that does not mean that calling for them is a waste of time.

Almost a third of young people are not undertaking any education by age 18 – compared to just one in five in France and Germany. And only one in ten workers are qualified at subdegree level (Level 4 and 5), half the share it should be given the make-up of the UK economy. Far too many young people peak at GCSE or A level equivalents in Britain, holding back future wages and careers.

One has to keep banging the drum.

I cant speak for the economists involved in the report. The report does not offer a detailed analysis of the balance of payments or a complex macroeconomic argument. There are many ways of funding an increase in investment. To imagine that one needs “pre-funding” in the form of a “pot of savings” is a fallacy. But the report points usefully to the role that pension funds might play as an ultimate source of domestic funding. They might also exert a useful disciplining role with regard to corporate management.

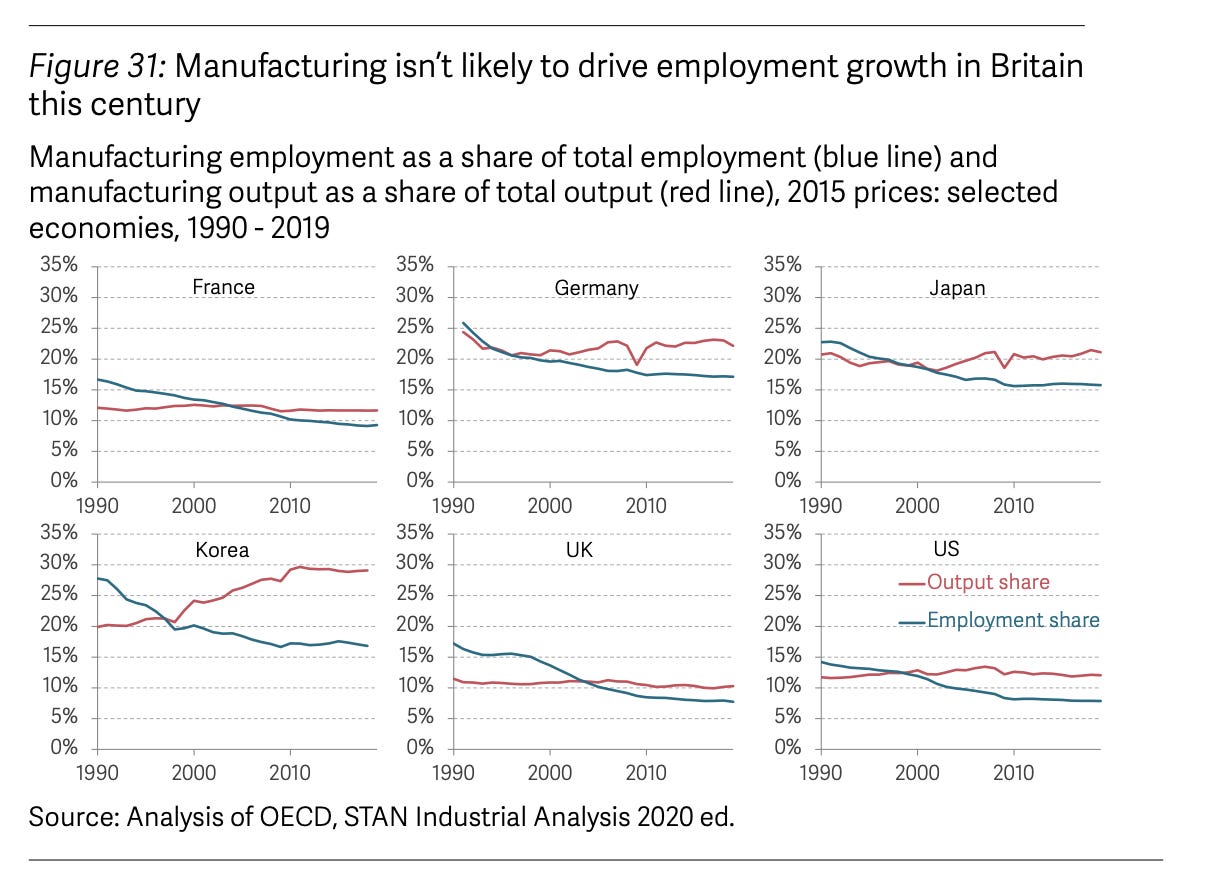

One particularly welcome aspect of the report is its tough-mindedness about potential sources of growth. Reviving manufacturing is not going to save the British economy or provide the basis by itself for a more equitable reconstruction of British society. The productivity differential in UK manufacturing relative to the rest of the economy is not dramatic. And as a sector it is too small to carry the overall economy.

The focus has to be on the largest sector in the economy, services of all kinds.

The 2030 Inquiry process has produced excellent reports on Birmingham and Manchester.

The report is also tough-minded in recognizing what can be achieved by economic policy in closing the inequality gap in a society like Britain in which the distribution of human capital is so uneven.

Raising the minimum wage, which has been one of the success stories of recent policy, should be a priority. This will come at the expense of some low-paid, low-productivity jobs. But that is no objection. It should be an announced aim of policy to shift the economy up the value-added scale. In this process some sectors will be winners and some will be losers. This should be welcomed even if it means that the cost of some services, notably restaurants and eating out, rise relative to other items in the consumption basket. Shifting the supply and demand side of the economy go hand in hand. It is only by doing both that you can achieve a rebalancing of the economy.

To drive this process:

‘Good Work Agreements’ should bring together workers and employers to solve knotty problems about the quality of work in their industry, setting minimum standards or ways of working to be adopted sector-wide. The first should be established in social care where a predominately female (77 per cent) workforce is often illegally underpaid, with warehousing and cleaning next in line.

But a better Britain cannot be built through the economy and the labour market alone. The problems of inequality and poverty are too severe to be addressed only by economic policy measures. For 20-30 percent of the population that are heavily dependent on benefits, improvement can only come with a comprehensive reform and redirection of the tax and benefit system to prioritize younger people and in particular low-income families with children and those struggling with disability.

All in all what is required is a major realignment of economic and social policy and this begs the question: how is the coalition for change to be fashioned?

This is where a report like the Resolution Foundation Enquiry reaches its limit. It must after all pretend to speak to the British polity as a whole. This is one of the responsibilities of centrist reformism. We have to extend the benefit of the doubt to all constituencies. In Britain right now this is particularly onerous.

The report’s authors must pretend to take the current Tory government seriously, even though any fair minded person must start from the conclusion that they and their predecessors are responsible for much of the mess the country is in and no better future for Britain can be built so long as they remain in power.

Whether or not a much better future can be expected from a Labour government is an open question. Starmer and his clique seem bent on betraying most things an intelligent progressive politics in Britain should be proud to stand for. But beyond their miserably impoverished and unimaginative vision there are parts of the Labour coalition that do back and do need a serious policy of reform. Let us hope that they gain the upper hand and that the leaderships posturing turns out to be a misguided and cynical attempt to appeal to “Middle England”.

In the mean time, the Economy 2030 Inquiry is an insightful and constructive response to Britain’s predicament.

***

Putting out Chartbook is a rewarding project. I am delighted that it goes out free to tens of thousands of subscribers all over the world. What makes the project viable are the contributions of reader like you. If you are not yet a subscriber but would like to join the supporters club, click here:

I was beside myself looking at the "productivity" in the financial services... The ultimate parasite, very productive at eating its host...

In Marx’s view, the greatest driver of increases in productivity is the relative strength of labour vis-a-vis capital. When workers have some leverage in the labour market, capitalists are compelled to innovate to raise productivity in order to get more bang for their buck. They’re also incentivised by the fact that investing in technical innovation in the production process can give them greater control over that process, curbing worker autonomy. The quite deliberate destruction of worker solidarity and trade union power in Britain over the last 40 years probably has more to do with stagnating productivity and declining wages than the undoubted mediocrity (and, indeed, mendacity) of the managerial class.