With the frustration of hopes raised by the summer offensive, it became clear that Ukraine is locked in an attritional struggle for survival. Ukraine has taught us how misleading macroeconomic aggregates can be as indicators of fighting power. But its remarkable battlefield success should not obscure the daunting challenge Ukraine faces.

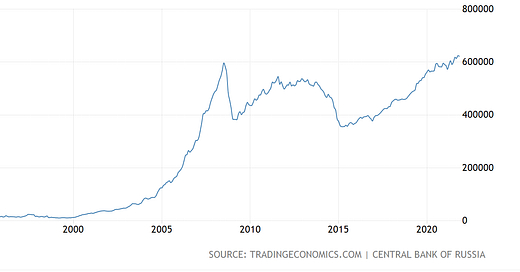

Take the data with a pinch of salt but in Purchasing Power Partiy terms Russia’s economy in 2021 was more than 8 times larger. that that of Ukraine - this is using the prices of an internationally standardized basket of goods as the basis for comparison. Measured in constant 2015 dollars, thus giving less weight to the lower domestic cost of living in Ukraine, Russia’s economy was 15 times larger.

This disparity means that even as it ramps up its war effort, Russia is devoting just over 6 percent of GDP to military spending. This is a serious effort, but far from overwhelming. Even under more serious sanctions in 2023 the Russian economy will have no difficulty paying for the imports it needs and no shortage of suppliers willing to trade with it on commercial terms. To manage this balance, Moscow needs only relatively light-touch controls.

Ukraine, by comparison, is fighting for its economic life. It could not function without outside assistance, which has to be haggled over from a coalition of supporters. Ukraine’s exports of agricultural commodities are important but they in no way compare to Russia’s vast slice of global energy markets.

The battlefield struggle focuses attention on issues of material production. And as far as the United States is concerned - as Ukraine’s most important foreign backer - it is indeed the capacity to produce ammunition, missiles and weapons that is the binding constraint.

The Ukrainian authorities like to trumpet their triumphs in surging drone production. They warn of the need to fill a “global ammunition gap”. Kyiv paints a picture of Ukraine’s economic future as the “arsenal of the free world”. Out of the experience of the war, Ukraine will grow a major new military-industrial complex on NATO’s Eastern flank.

These productivist stories are eye-catching. And it is obviously true that you can’t fight the kind of battles raging in eastern Ukraine without massive amounts of ammunition. But the fact that we can concentrate on them at all, the fact that Kyiv is not rocked by surging inflation or a collapsing currency, reflects a remarkable achievement in stabilizing Ukraine’s macroeconomy.

Over the summer, despite the frustratingly gradual advance of the offensive the tone of the economic narrative turned surprisingly optimistic. This doesn’t grab the headlines as much of talk about weapons, but it is essential. If it is true that we can afford anything we can actually do. It is also true that it is very hard to focus on actually doing anything if your macroeconomic balance - the balance of aggregate demand and supply - is fundamentally out of wack. Under those conditions, inflation and questions of how to get your hands on foreign currency to pay for imports, will disorientate the productive system and leave households struggling.

This balance is even harder to strike when your economy is contracting, as Ukraine’s was under the impact of the Russian assault.

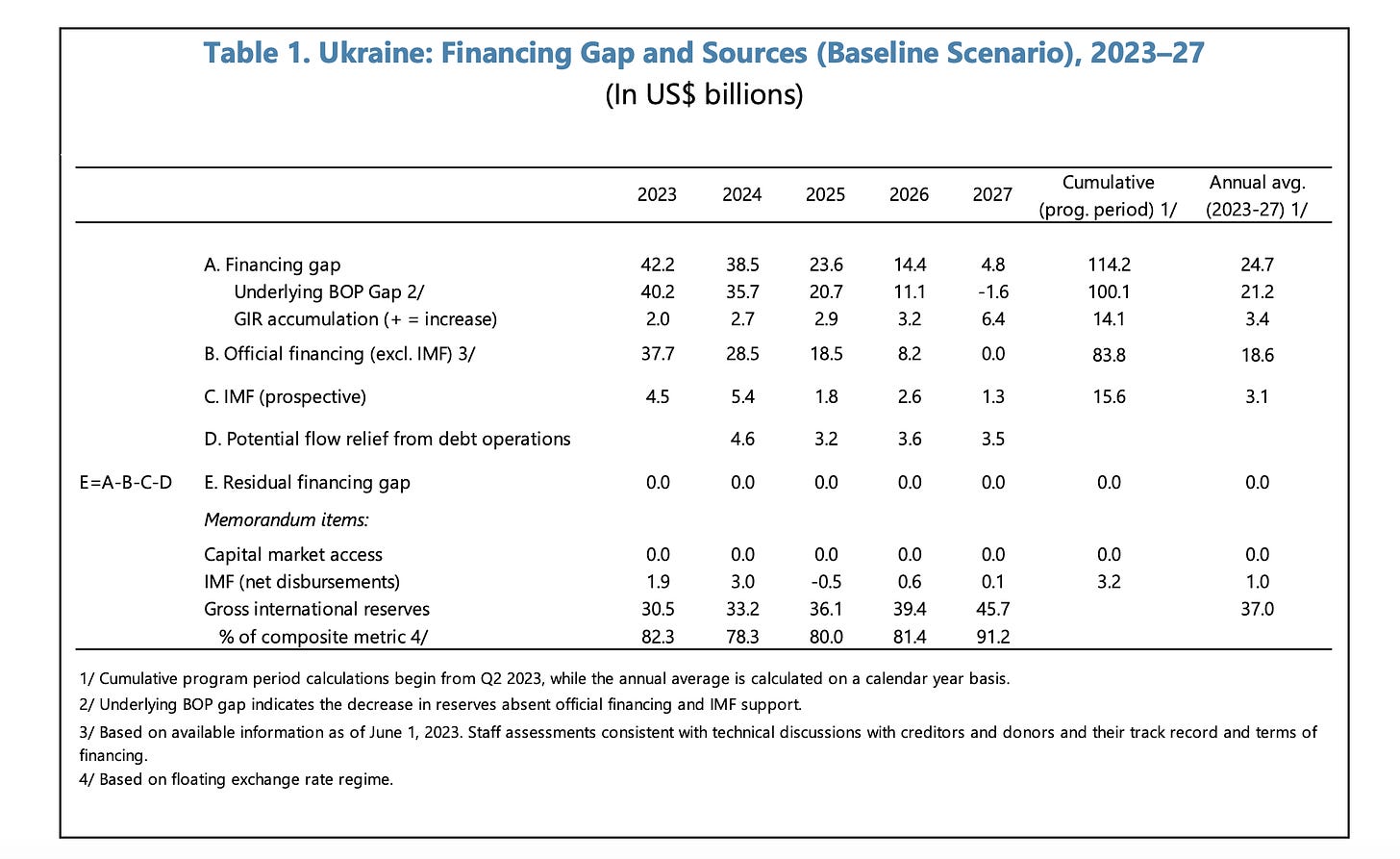

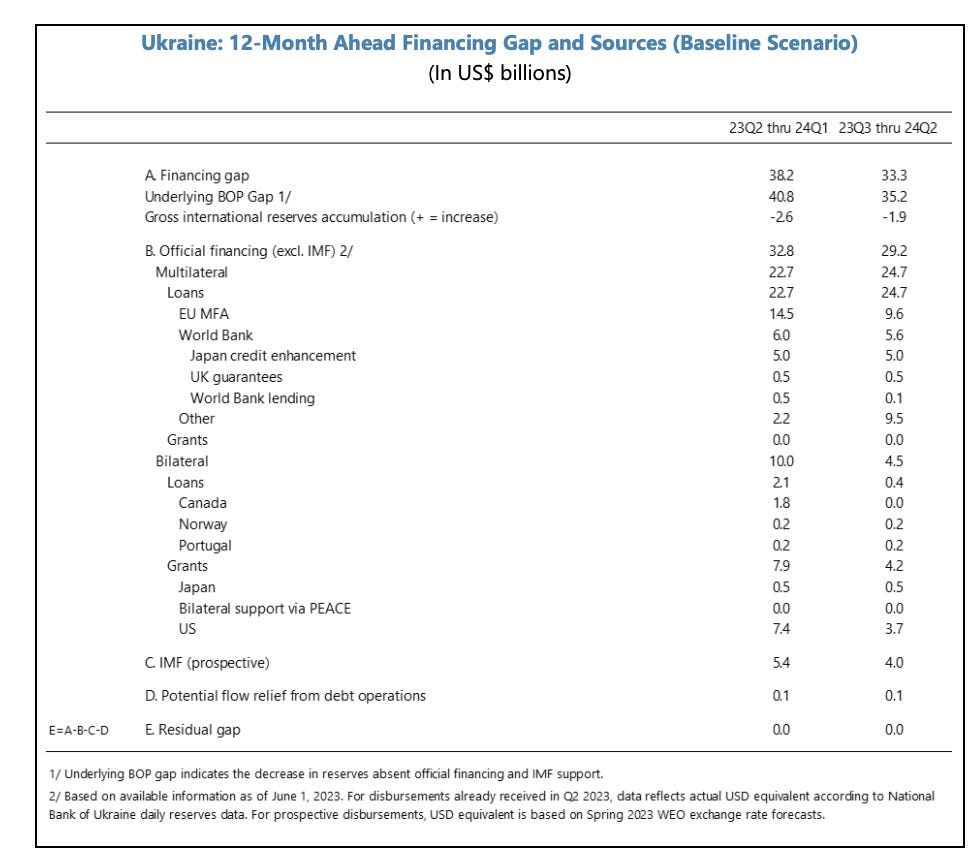

Source: IMF

The success of stabilization is represented by the fact that in the fourth quarter of 2022 Ukraine’s economy stopped collapsing. Since then GDP has stabilized at 30 percent below its prewar level and the worst case scenario - in the event of further massive Russian attacks on the energy system - now foresees a relatively modest further contraction. The scale of the invasion shock becomes even clearer when we pan back to view the last decade.

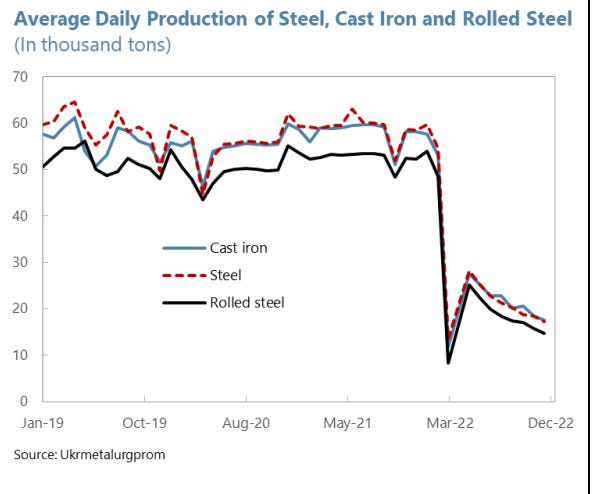

Ukraine’s heavy industrial sector was completely devastated by the outbreak of the war.

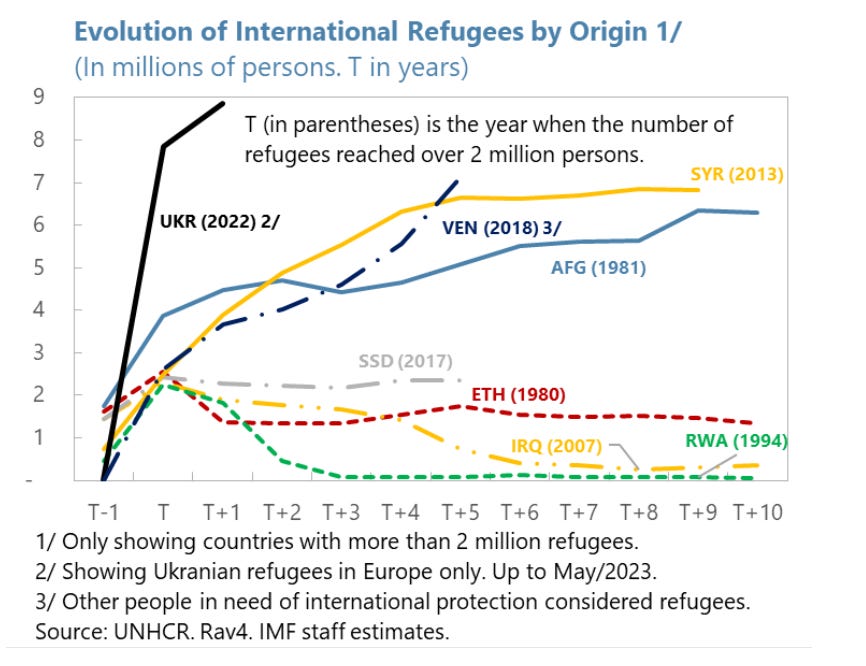

This collapse in economic activity reflects the disruption and destruction, the mobilization of workers for war and the flight of millions of Ukrainians out of the country. Ukraine’s exodus was the biggest and most rapid refugee movement seen worldwide in almost half a century.

The war has left a huge percentage of Ukraine’s population dependent on humanitarian assistance. In 2022, 15.8 million people in Ukraine received different types of humanitarian assistance.

Any talk of stabilization is thus strictly relative.

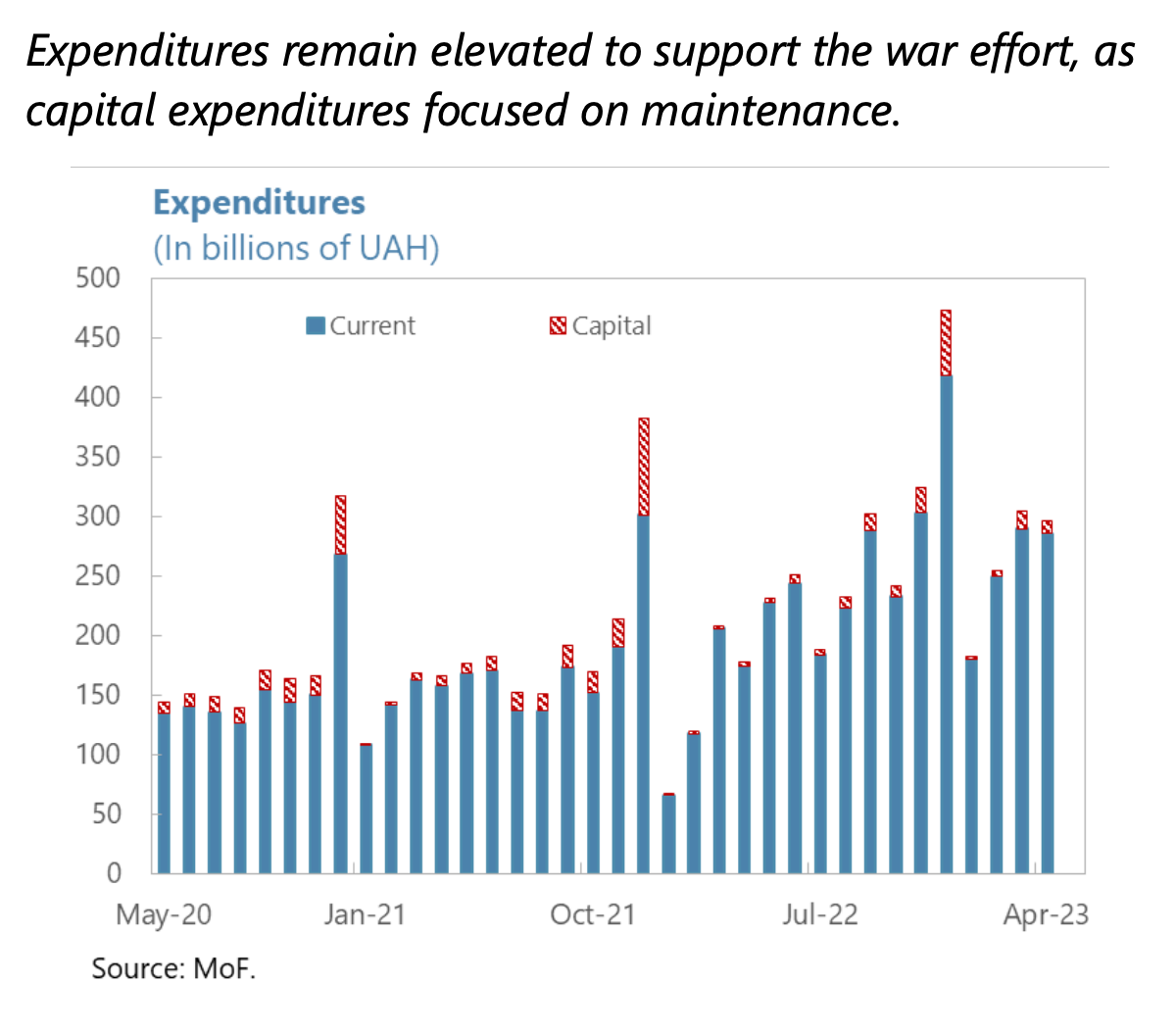

The war has not only disrupted normal economic activity, it has also forced a dramatic mobilization of resources in the hands of the state. This is seen in figures for state spending. These are not broken down in detail, but they show a step change from a prewar level of around 150 UAH per month to a current level, which fluctuates between 250 and 300 UAH per month.

Source: IMF

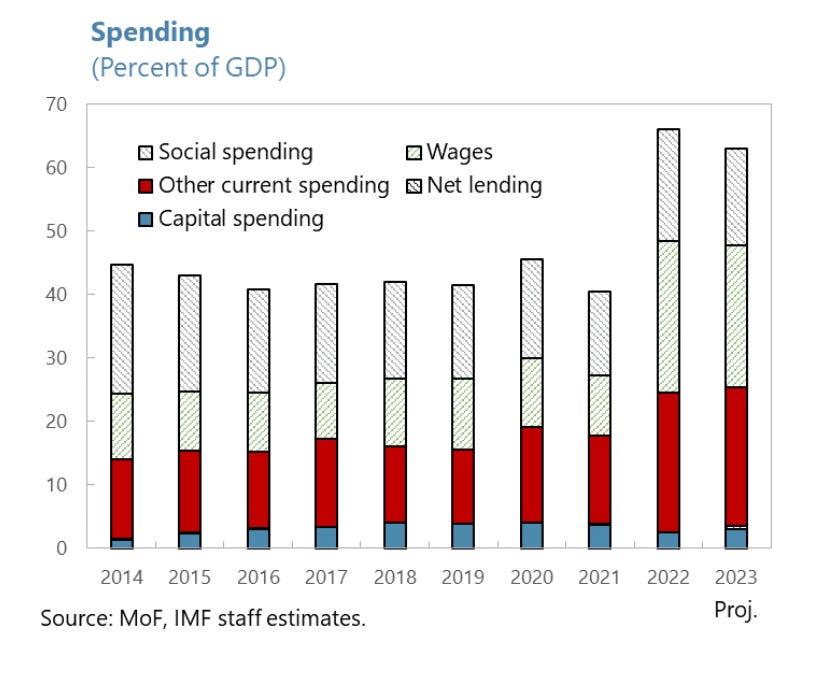

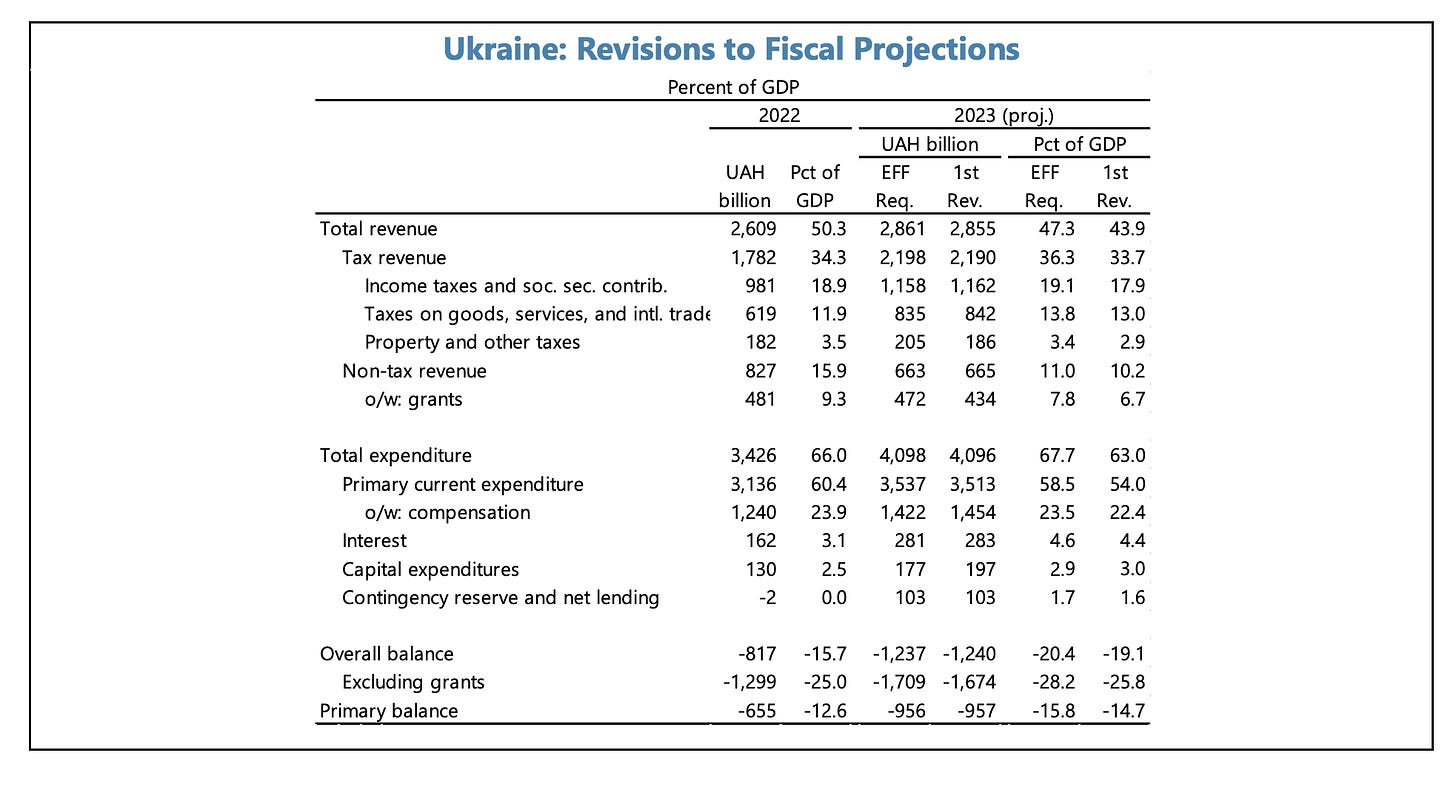

At the same time as spending surged, in 2022 GDP collapsed. The result was to drive government spending as a slice of the smaller economy from 40 to 66 percent.

The IMF now hopes, that as the economy begins to recover, even as government spending on the war increases, its share of gdp will stabilize around 65 percent. Emblematic institutions of the “state economy”, like state banks, which were previously slated for privatization, are now playing a key role in managing the war economy. What Kyiv is not managing to do, given the shock to its economy and the scale of the war effort, is to “pay for itself”. This is true in a double sense. Ukraine’s public budget is in substantial deficit. It cannot raise enough tax or other revenue to cover government spending.

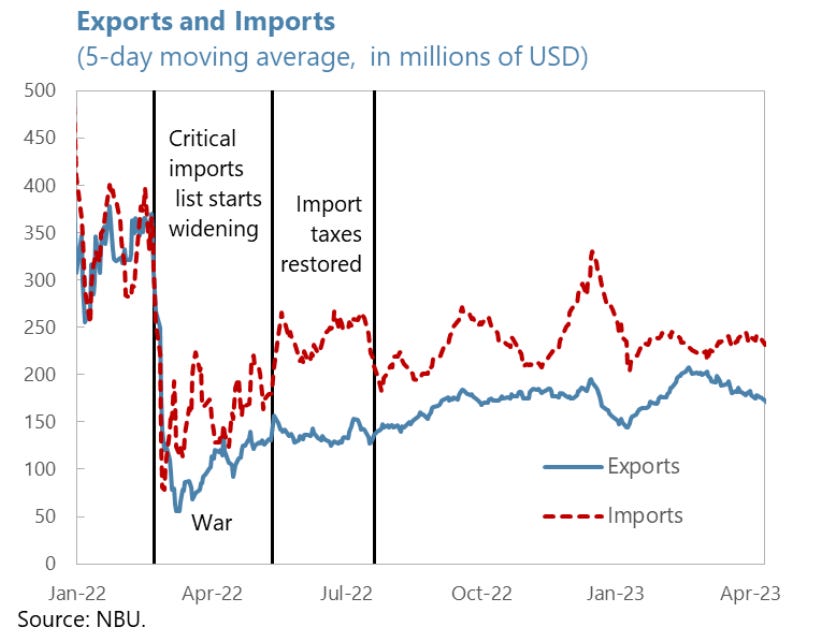

There is also a gap between Ukraine’s need for imports and its ability to pay for them through exports. Ideally, Ukraine would be importing more than it did before the war to make up for the shortfall in domestic production. The best thing for a war economy is to dial back all non-war production, including exports, and to rely as heavily as possible on imports paid for by long-term loans and grants. And when it comes to weapons, Ukraine is dong exactly that. But overall, as Ukraine’s economy imploded in 2022, its imports fell sharply. Normally that might be expected to produce a shift into trade surplus. But the opposite happened. As a result of Russia’s attack, exports fell even more than imports and Ukraine slid into a large monthly deficit.

A “twin deficit” - both in the government account and on the foreign trade account - on the scale seen in Ukraine in 2022 is symptomatic of a country on the edge of a doom-loop of macro-financial crisis. For much of 2022 it was fueled by Kyiv’s resort to monetary financing to cover the budget deficit. Rather than taxing or borrowing in stable ways either at home or abroad, Kyiv was effectively monetizing deficits with the central bank. That depreciated the currency, which in the short-run pushed the price of imports up, exacerbating inflationary pressures.

Back in Chartbook 205 I focused on the struggle that ensued between the government and Ukraine’s central bank in the autumn of 2022. The success of stabilization consists in having stopped this doom-loop. The authorities are no longer using monetary financing and are committed in their discussions with the IMF to refraining from it in future. The quid pro quo is a large flow of foreign financing.

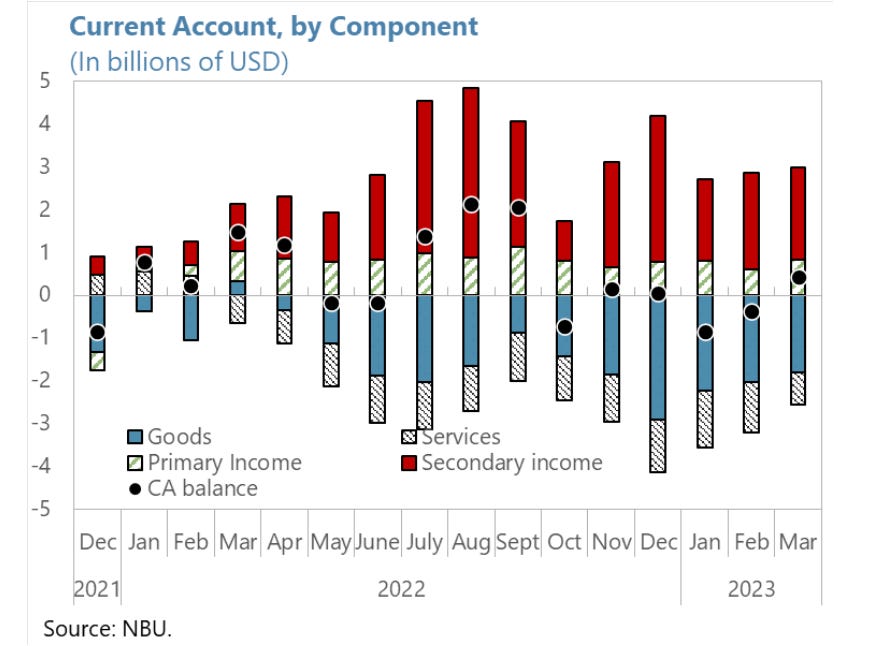

You can see this in the current account data, where the red bar for “secondary income” records foreign financing of the Ukrainian war effort in its external account.

And the same flow of foreign funds also shows up in the government accounts as grants.

As the IMF comments in its review of Ukraine’s situation published in July 2023, the key to preserving Ukraine’s fragile stabilization is avoiding a return to the doom-loop that appeared to be emerging in the early phase of the war:

“Concessional financing from international partners and donors is expected to form the majority of net borrowing for financing the 2023 deficit (net external financing of US$29.7 billion out of the total net general government financing of US$33.1 billion) and the remainder of the program period. Domestic bond financing is expected to meet a smaller share of financing needs (net bond financing of US$3.4 billion for 2023); no monetary financing is envisaged … The authorities remain committed to avoiding monetary financing of the budget. No monetary financing is expected under the baseline (Indicative Target). As a contingency, such as due to a shortfall in external financing or unexpected financing needs, monetary financing is expected to be used only after all other options have been exhausted, and in limited amounts. In line with the recommendations of the 2023 Update Safeguards Assessment, the NBU and MoF are working on a framework for monetary financing, to be in place by end-July, that will specify the key triggers and terms for accessing monetary financing, as well as the conditions for using different types of such financing (e.g., bonds, short-term advances). Together with more frequent coordination on fiscal financing needs, this framework should help limit ad hoc requests and mitigate the risks of excessive monetary financing.”

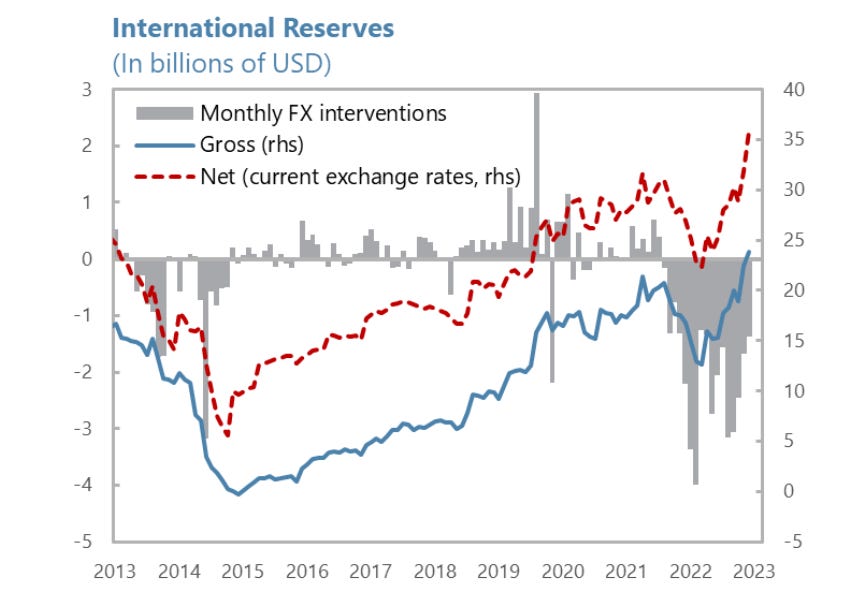

With the backing of foreign donors Ukraine’s central bank rebuilt a cushion of foreign exchange reserves.

Then, with the economy no longer in free fall and the central bank no longer financing the war by “printing money”, in the summer of 2023, the Ukrainian central bank began preparing to loosen many of the restrictions put in place to protect the foreign exchange value of the currency in the first year of the war.

Rather than panicking at the prospect of liberalization, the “street rate” for Ukrainian hryvnia converged with the central bank’s official rate. In June 2023, Ukrainian households sold more foreign currency than they bought for the first time in almost a year. And global financial markets rallied around Ukrainian bonds.

Speculators betting that Ukraine’s economic conditions will continue to improve started buying up Ukrainian foreign debt, on the assumption that the eventual restructuring - no one doubts the need for that - will produce a better recovery rate than previously thought, in other words that Ukraine will pay them more. As the FT reported in early August:

Ukraine’s government bonds have surged in price over the past two months as investors grow more optimistic about how much of their money they will get back in an eventual restructuring of the war-torn country’s … $20bn of international bonds. … (bond) prices have climbed by more than 50 per cent since early June — putting Ukrainian bonds among the best performers in global fixed income markets this year — as a steady flow of foreign aid bolsters Kyiv’s currency reserves, while forecasts for the country’s economy have recently become somewhat less bleak. …. Kyiv’s foreign reserves have climbed to an all-time high of $41.7bn as financial aid from western countries continues to flow … Investors say that the IMF’s review in June of its four-year $15.6bn loan programme to Ukraine, which allowed Kyiv to immediately withdraw $890mn for budget support, has also helped fuel the recent rally. … Ukrainian debt continues to trade at levels that imply a restructuring is a certainty and creditors will receive a harsh writedown of the value of their bonds. But the market’s assessment of how much investors are likely to recover has risen. A dollar-denominated bond maturing in September 2025 currently trades at 31 cents on the dollar, up from 20 cents in early June. … The biggest holders of Ukraine’s international bonds are BlackRock, Pimco and Fidelity, according to filings data compiled by Bloomberg. “It’s a pretty good return in two months,” said Giancarlo Perasso, the lead economist at PGIM fixed income, which also holds some Ukrainian debt.

With confidence stabilizing, on October 26 the National Bank of Ukraine cut the benchmark interest rate by four percentage points to 16% on Thursday, deeper than the 18% forecast in a Bloomberg survey of economists. As Bloomberg reported:

“We are seeing and responding to a sustainable trend of declining” inflation, Governor Andriy Pyshnyi told reporters in Kyiv. The bank said it will be gauging the market’s response to a loosening of capital controls on the nation’s currency. The resilience of Ukraine’s wartime economy and falling prices have prompted rate setters to begin easing controls and deliver cuts faster than initially planned. Growth will return this year after the fallout from the destruction of infrastructure, the throttling of Ukraine’s key grain exports and population displacement.

This is a remarkable turnaround from the mood of mounting alarm and internal dissension visible amongst economic policy-makers in Kyiv this time last year. And it is all the more remarkable given that the outlook in military terms is a grim as it is. As Bloomberg notes:

… the central bank sees war risks extending through 2024 — a previous assessment cited mid-next year — as a grinding counteroffensive makes little progress in recapturing Russian-controlled territory and winter weather threatens to halt any advances. Ukraine’s military has pledged to press on through colder temperatures. The central bank said it will continue with monetary easing into next year only if economic risks subside. The impact of the headline cut is tempered as other instruments, such as rates on deposit certificates, the most relevant indicator in the current environment of excess liquidity, remain steady.

The precarious stabilization thus depends on two things. Ukraine manages to continue the war as a grinding attritional struggle and the flow of external finance continues.

This of course implies a network of new obligations, which will ultimately have to be worked out in some restructuring, peace and reparations deal. And private creditors will be part of that deal.

Elements of the financing are secured long-term, notably the EU’s commitment.

Source: IMF

It is a complex patchwork. But it is in this listing of donors and lenders and the shape and size of their commitments that the material underpinnings of the Western power bloc are spelled out.

Source: IMF

As Schumpeter said, it is in budgets like this you you can hear the thunder of world history.

The key questions going forward are, will this patchwork be enough to sustain Ukraine it is vastly unequal struggle with Russia. And secondly, where in this balance the United States will figure. Will the Biden administration secure Congressional approval for more aid for Ukraine and what are the prospects beyond 2024.

Take away foreign sponsorship and Ukraine's economy would basically be zero.

That before the war, Ukraine was rivaling some Sub-Saharan African countries for GDP per capita and corruption perceptions is also hardly cause for cheering.

I don’t think this post ages well.

Ukraine is ceasing to exist.