Perhaps it is the jittery state of the US Treasury market, but people have been asking. Can America afford two wars at once? The two wars being in Ukraine and Israel/Palestine.

In the last 48 hours both President Biden and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen have been at pains to emphasize, that, of course, America can.

On the flagship TV news show, 60 Minutes Biden said:

“We’re the United States of America for God’s sake, the most powerful nation in the history — not in the world, in the history of the world. We can take care of both of these and still maintain our overall international defense.”

His facial expression as he delivers the line is well worth checking out.

Yesterday, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen doubled down by spelling out the financial side. It was simply a matter of coming up with the funding and that depended on the Republicans, who are in chaos over the House Speakership and reluctant on Ukraine.

It is worth lingering over the slippages here. For one, much as it suits political rhetoric to suggest otherwise, much as the “two wars doctrine” was for decades central to US defense strategy, America is not actually a party to either conflict. Secondly, to throw the two conflicts into a single pot, as in the “two wars”-framing is tendentious in the extreme.

Cameron Abadi and I got into these issues at some length in the podcast this week. You can listen and read more here.

One really has to ask what purpose is served by a public discussion - driven both by journalists and politicians - that describes America’s engagement as the equivalent of war and then elides one conflict with the other.

Ukraine is fighting for its survival against a Russian military with massive superiority and a Russian economy that is far stronger than that of Ukraine. By comparison, Israel is conducting a counterinsurgency operation with overwhelming numerical and qualitative superiority against Hamas, which is fighting with light weaponry in a confined urban kill zone. On Israel’s northern border, there is a threat of attack by Hezbollah, which is a more formidable force than Hamas. But, on that front too, Israel has huge advantage in military terms. The situation is altogether unlike that in 1973 when Israel faced invasion from the powerful militaries of Syria and Egypt backed by the Soviet Union. Today Egypt is bankrupt and Syria is a wreck, whilst Russia’s resources are tied in Ukraine.

In 1973 the United States mounted a serious effort to back Israel in its battle for survival. It delivered huge amounts of aid.

Source: USAFacts

Today, Ukraine receives aid to the tune of tens tens of billions of dollars but given the strength of the Russian opponent, it is enough to do little more than hold the balance. Israel for its part receives just shy of 4 billion per annum, which is no doubt welcome and includes important technologies. But given Israel’s wealth - it has a GDP of almost $500 billion - and technological sophistication and the weakness of its enemies, US aid is a matter of securing absolute dominance rather than survival. It serves political needs for both sides rather than military necessity.

And clearly, neither the aid for Ukraine nor that for Israel in any way stretches America’s resources. As the DoD reports:

On March 9, 2023, the Biden-Harris Administration submitted to Congress a proposed Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 Budget request of $842 billion for the Department of Defense (DoD), an increase of $26 billion over FY 2023 levels and $100 billion more than FY 2022.

This presumably is what both Biden and Yellen mean when they stare into the camera and say, “We’re the United States of America for God’s sake”.

But, even if America were actually engaged in a major conflict, as it was in Iraq and Afghanistan, and assume its spending was many times its current level of assistance to Ukraine and Israel, America could “afford” that too.

That point was driven home by a telling twitter exchange. Reading Yellen’s interview, I was struck by the way she turned the issue of Congressional approval to partisan advantage. Then, Stephanie Kelton, one of the leading voices of Modern Monetary Theory took the point further. As she stressed this is ultimately a question of political priorities.

This is basic Keynesian macroeconomics. Assuming there is some margin of available resources, or a willingness to redistribute resources between economic sectors, then, when it comes to major national priorities, budgetary constraints are never binding. Budgets are convenient fictions, defensive positions on which to fight political battles for and against “entitlements”, for instance, not real economic constraints.

The current instability in the US Treasury market does not detract from this point. If the authorities wish to stabilize that market, all that needs to happen is for the Fed to step back in. That would, of course, reverse the “normalization” of monetary policy. It would tend to ease monetary conditions and perhaps slow down the pace of disinflation. But that is a political choice.

But our current situation also drives home another point. If Keynes was right that we can afford anything we can actually do, then the political implications are heavy.

The insights of left Keynesianism, MMT et al are generally taken to be liberatory, freeing democratic politics from the shackles of fiscal rules, cases in point being America’s debt ceiling or Germany’s “debt brake” (Schuldenbremse). What actually constrains our choices, are the scarcity of economic resources, available technologies and our ability to reach political agreement. Questions of finance and “affordability” are secondary, organizational and technical matters. They reduce to matters of law and accounting. These are not trivial. They have their own institutional ramifications. But they are malleable.

This may be liberatory, but it also raises the political stakes. If we espouse the Keynesian vision we can no longer appeal to budgetary constraints to rule out options of which we disapprove. If one side favors war, or even two wars, or three, fiscal arithmetic does not stand in the way. What does are ethics, or politics or raison d’état.

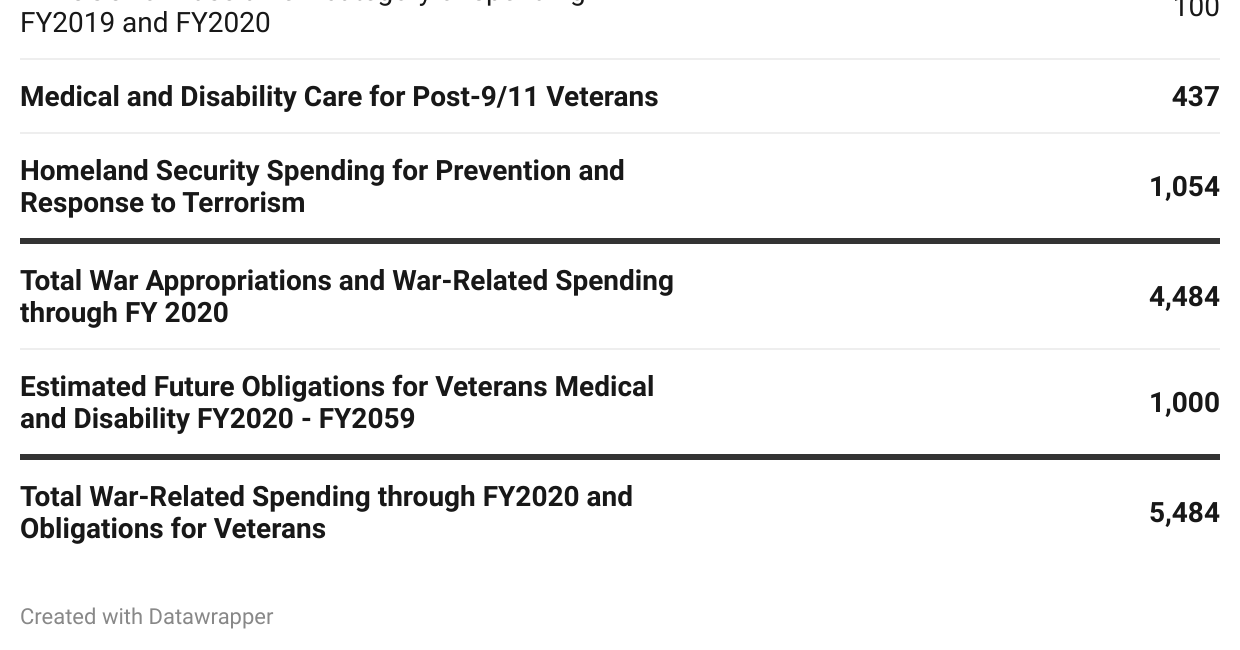

I made this point back in 2021, on the occasion of the Afghanistan withdrawal, with regard to the question of how the Left should think about the question of how America paid for the Global War on Terror.

Returning to the question now, Keynesian logic once again forces us to face the politics directly. The question is not whether America can afford to funnel weapons into the war in Ukraine and to back Israel’s destruction of Hamas, but to what extent it should do so. The Keynesian logic is salutary because it forces us to face the political and strategic questions directly.

Furthermore, it points us to what are actually the real constraints. Insofar as there are limits on what America can deliver, they are not financial - dollars and cents - but industrial and logistical. How many weapons and munitions can the USA currently supply.

Since the start of Russia’s assault on Ukraine we have got used to talking about the manufacturing of missiles and shells. It fits the mood of the moment with its preoccupation with “industrial policy”. I have written in this newsletter about the Javelin missile that for a while had a starring role on the Ukraine battlefield.

What Israel is now asking for are both defensive and offensive munitions. They need defensive interceptors for the Iron Dome system. As the FT reports:

The interceptors, also known as Tamir missiles, are co-produced by US defence contractor RTX, formerly Raytheon Technologies, and Israeli group Rafael Advanced Defense Systems and assembled in Israel. RTX declined to comment on the current state of Tamir production.

But they are also requesting precision ordinance and ammunition for their tanks and heavy artillery with which to target Hamas and to bombard Gaza.

Within a matter of days of its counterattack against Hamas, Israel reported having dropped 6000 bombs. That is a heavy aerial bombardment. Artillery will add further to the destruction.

In 2014, in the last major ground incursion into Gaza, Israel fired 14,500 tank shells and 35,000 other artillery shells during the conflict. In the aftermath, there were major questions about the heavy use of unguided artillery against targets in Gaza.

Damaging as it was, this kind of bombardment, delivered over weeks, pales by comparison with the artillery war in Ukraine. During the current couneroffensive Ukraine has been rationing itself to “6,000 rounds DAILY, Ukrainian MP Oleksandra Ustinova told CNN, but the military wants to shoot more than 10,000. Even that is a fraction of the 60,000 shells that Russia was using at the peak of its barrages this year, per an Estonian and Ukrainian government analysis. All in all, Kyiv needs some 1.5 million artillery shells annually, according to the CEO of one of Europe’s largest arms manufacturers, Rheinmetall.”

With Western deliveries to Ukraine already running at more than 2 million shells, manufacturers on both sides of the Atlantic are scrambling to meet those demands, ramping up production.

Since it will take more than a year to reach full-scale production, ammunition needs are being met from stocks. Earlier the US transferred 300,000 rounds of ammunition from stocks prepositioned in Israel, to Ukraine, placing new orders with South Korea to make up the difference. Israel will presumably want some of that back.

In early October Defense News reported on the Pentagon’s urgent efforts to increase the quantity of artillery production that can “actually” be produced:

The U.S. Army said it awarded $1.5 billion in contracts to nine companies in the U.S., Canada, India and Poland to boost global production of 155mm artillery rounds. Over the last two weeks in September, the service finalized a flurry of contracts that “resourced each major component, material or required production process to maintain momentum for the goal of 80,000 projectiles per month by the fourth quarter of fiscal 2025,” it said in an Oct. 6 statement. Army officials have recently stated that 155mm artillery munition production will increase to 28,000 per month in October, which is double what the Army was producing at the start of the year. The plan is to build roughly 60,000 a month in FY24, reaching 80,000 by FY25. By FY26, the plan is to build 100,000 a month

Macabre as it is, what the “two war”-question revolves around is not dollars and cents, but physical production capacity. The rate limiting factor is the allocation of the scarce means of destruction.

And as left Keynesians always remind us, “we spend it on ourselves”, or to be more precise, we spend it on the fortunate recipients of government largesse. As the FT reports:

Shares in Lockheed, RTX, Northrop Grumman and General Dynamics — four of the Pentagon’s big contractors — have risen sharply since Hamas’s attack on October 7.

What Wall Street sees in the crisis is “opportunity”. Public spending is private profit.

> Israel is conducting a counterinsurgency operation

Conducting it since 1948, eh?

Very clean analysis. It fights against panic. It might have delved a bit into the question of whether the US is doing itself any good by funding the guards on the wall of a prison holding the original inhabitants of the land, but I know that is outside the purview of your article. Good work.