The banking turmoil in March 2023 brought renewed attention to bank deposits. A quickening of deposit outflows at several banks – in part due to rising interest rates – prompted financial stability concerns. Rate hikes have also created incentives for depositors to shift away from banks in search of higher returns (Afonso et al (2023)).

The latest issue of the BIS quarterly report features a fascinating analysis by Bryan Hardy and Sonya Zhu of funding flows during the crisis associated with the failure of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse.

By looking at flows between global banks, the non financial system (businesses and households), nonbank financial institutions and the central banks, they are able to present what you might call an ecological account of that sudden burst of turmoil.

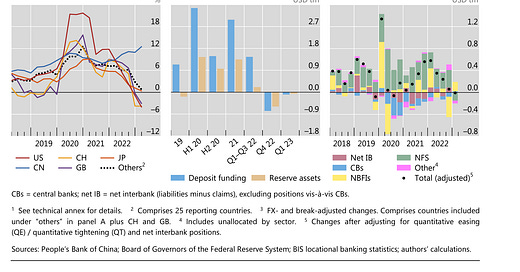

The scene was set at the end of 2022 and early 2023 when the inflow of deposit funding. to the global banking system slowed to zero and then went into reverse.

The amounts were small. An outflow of “$0.14 trillion, or 0.5% of the $25 trillion in amounts outstanding” but this is the first time in 21 quarters that the BIS has ever seen a negative flow. The impact on the banking system was compounded by the tightening of central bank policy.

Quantitative tightening reversed QE. Rather than buying bonds and flushing the banking system with reserves, the central banks were now selling bonds, absorbing payments, mainly from non banks, but shrinking bank reserves.

As the mini-crisis built up and interest rates rose, deposits moved from banks non-bank financial institutions (NBFI) like Money Market Mutual Funds, which then recycled the funding to banks, to the tune of $0.17 trillion.

These shifts were concentrated in particular jurisdictions. As the BIS comments

Banks in the United Kingdom in particular saw the largest increase in local funding from NBFIs – $50 billion – alongside a $43 billion decline in NFS deposits (Graph 7.A). The picture was similar in Canada and Italy.

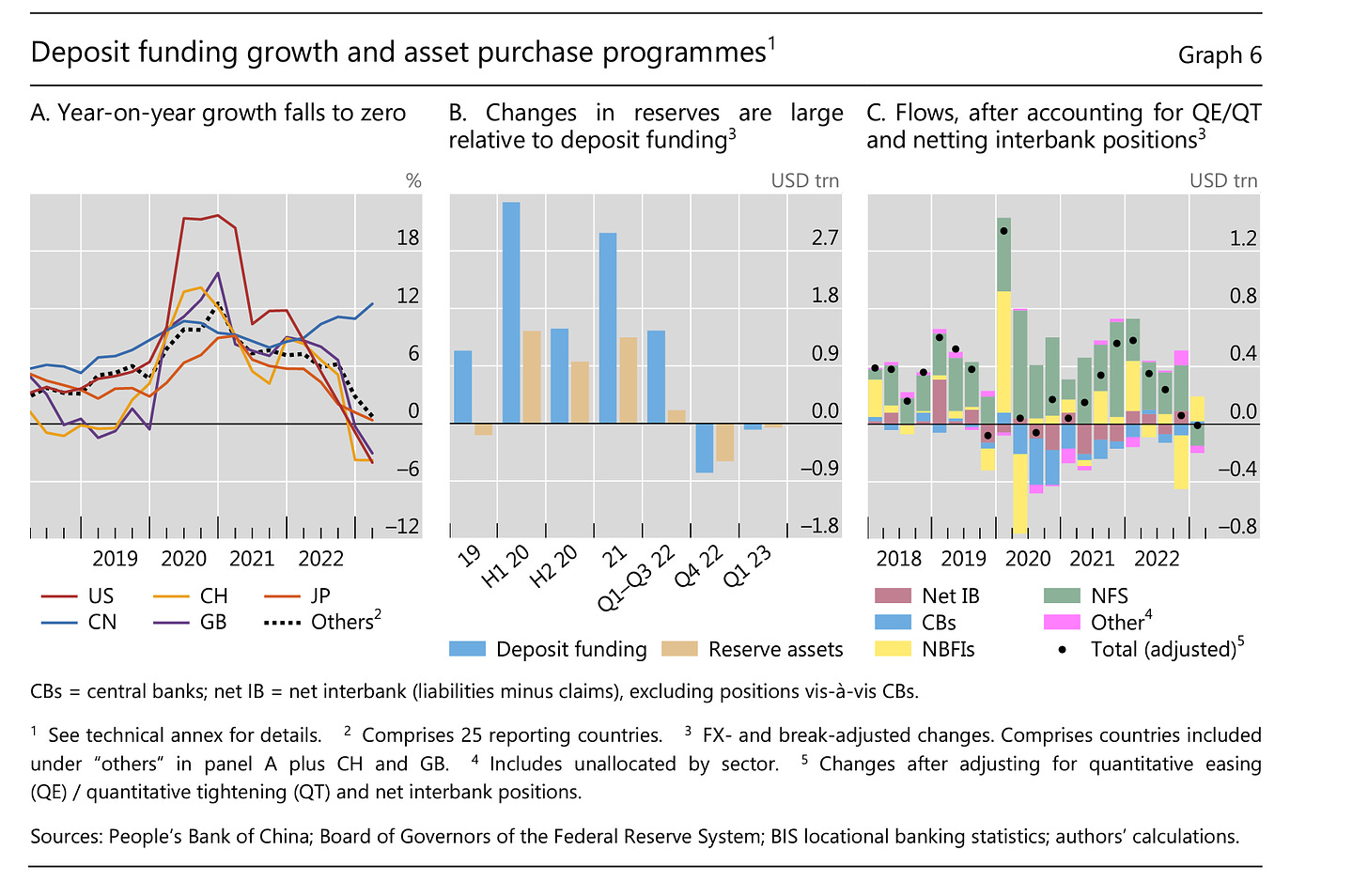

Most quantitatively significant for the global financial system are NBFI in the US which saw a huge inflow, much of which was then passed on in funding to non-American banks.

Dollar funding from NBFI in the US to global non-American banks is a key part of the “dollar system”. As Iñaki Aldasoro, Bryan Hardy and Sonya Zhu point out in a special box, this funding flow surged in the spring of 2023.

The dollar funding provided to non-US banks by MMFs (located both inside and outside the United States) rose by almost $550 billion (or 53%) during the first half of 2023 (Graph A1.D). Most of this increase (+$439 billion) came in the form of repos provided by MMFs located in the US

But as March 2020 demonstrated, that flow can also go into reverse.

As the BIS authors comment rather dryly:

The key role of NBFIs in general – and MMFs in particular – as funding providers to banks underscores their growing interconnectedness. As most recently evidenced by the March 2020 market turmoil, MMFs can be a flighty source of funding. Stronger reliance on them can thus be a source of bank vulnerabilities.

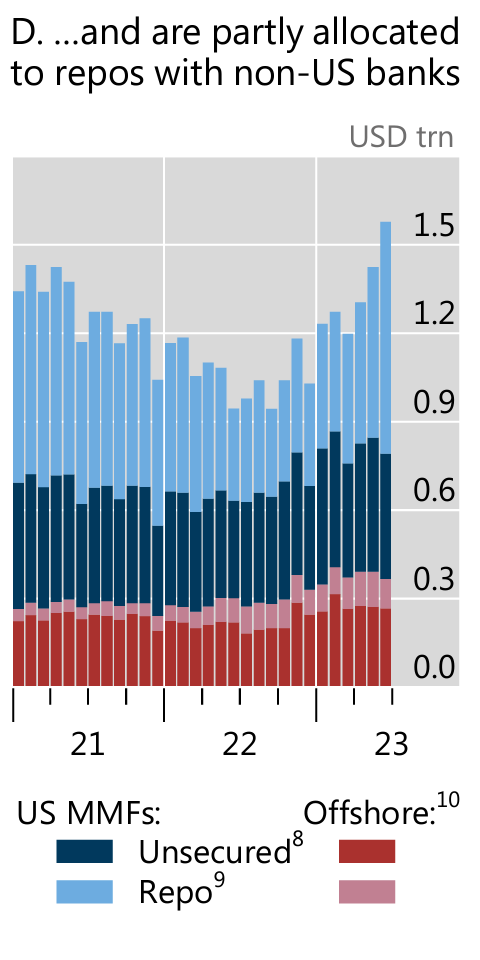

In the spring of 2023 it was not global banks in general but Swiss banks in particular that were in trouble and this stands out clearly in the BIS data.

From Q2 2022 to Q1 2023, both resident and non-resident non-banks (NFS and NBFI) reduced their funding of international banks in Switzerland – by about $30 billion and $180 billion, respectively (Graph 8.A). This amounted to a 12% year-on-year fall in bank deposit funding, the largest since the Great Financial Crisis. Part of the decline corresponds to a decrease in reserves, which fell by about $120 billion.16 Adding net funding from the banking sector, there was a decline of $71 billion in deposit funding for international banks in Switzerland not connected to the decrease in reserves. This loss of deposit funding was compensated by the $102 billion of funding provided by the central bank (see Graph 2.C).

Buried in this dry prose is the collapse of Credit Suisse and the extraordinary taxpayer-backstopped windfall handed to UBS, which was there to pick up the pieces.

This was a dramatic and irreversible shift in Switzerland’s political economy, but what did not happen was a general run on the Swiss banking system. Some Swiss deposits moved to banks abroad, but the majority moved within the Swiss banking system to less international, cantonal banks.

The overall drop in domestic Swiss deposits from Q2 2022 to Q1 2023 was nevertheless small (a 1% change), as most of the deposit funding decline from international banks ended up at other banks in Switzerland.

Overall, despite a few notable casualties, the mini-panic of 2023 was contained. Those failures had idiosyncratic causes, notably bad management and poor regulation. But in the background the message from the BIS is clear.

Though the redirection of the flow of non bank deposits by way of non-bank financial institutions, like MMMF, was benign in the first instance, it continues a trend that has been ongoing for a decade and may harbor serious run risk. We had a harbinger of that in 2020. We should expect more to come.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.