The news about Israel has three faces - the escalating violence of the occupation, the constitutional crisis unleashed by Netanyahu’s far-right government and an economic success story that has made Israel the darling of the tech economy and an attractive partner for international players including the oil-rich Arab world. On the podcast, Cameron Abadi and I attempted to draw some of these facets together. You can listen to our conversation here.

***

In much recent commentary focused on Israel’s domestic constitutional crisis, there are suggestions that an illiberal turn in Israel’s politics might put in jeopardy its flourishing high-tech economy and thus its overall economic strength. This is no doubt an appealing narrative for those who think of globalization and high-tech as forces of liberalization. But how plausible is this scenario in light of Israel’s 75-year history?

If we stand back and draw a sketch map of the evolution of Israel’s political economy, what predominates are macroeconomic forces and fundamental issues of national security strategy not internal politics or culture wars. For the last twenty five years, despite the narrative around the putatively liberal and cosmopolitan culture, Israeli politics and grand strategy have been balancing considerable tension between its growth model, its unresolved security situation and mounting domestic socio-economic pressures. If high-tech worries about Netanyahu’s illiberalism were to be the straw that breaks the camel’s back it would be, to say the least, a surprise.

****

If we review Israel’s 75 years history, we can distinguish four distinct phases each defined by Israel’s insertion into a wider economic and security context:

The phase of construction from the 1940s to 1967

The phase of war and crisis from 1967 to 1985

The moment of the peace process and globalization from 1985 to 2000

The phase of national security neoliberalism or “hawkish neoliberalism” (Krampf) from 2000 to the present.

Each of these phases is associated with its own historical narrative. But rather than treating each as radically distinct, we need to connect them together. This is important to avoid falling into the trap of contemporary clichés, which are heavily invested in the idea that modern Israel and its “high-tech” “entrepreneurial economy” mark a radical break with Israel’s “socialist” past. In fact, a deep continuity connects each phase, a continuity made up of the evolution of Israel’s ruling elite - a deliberately capacious phrase - and its shifting strategies of power and accumulation. Though analysts from different camps put more emphasis on the state (Krampf) or capital (Bichler and Nitzan), they agree in seeing an intelligible and continuous evolution of strategies, rather than a series of dramatic discontinuities. If there are discontinuities they come, above all, from the side of national security rather than issues of liberalism or illiberalism.

***

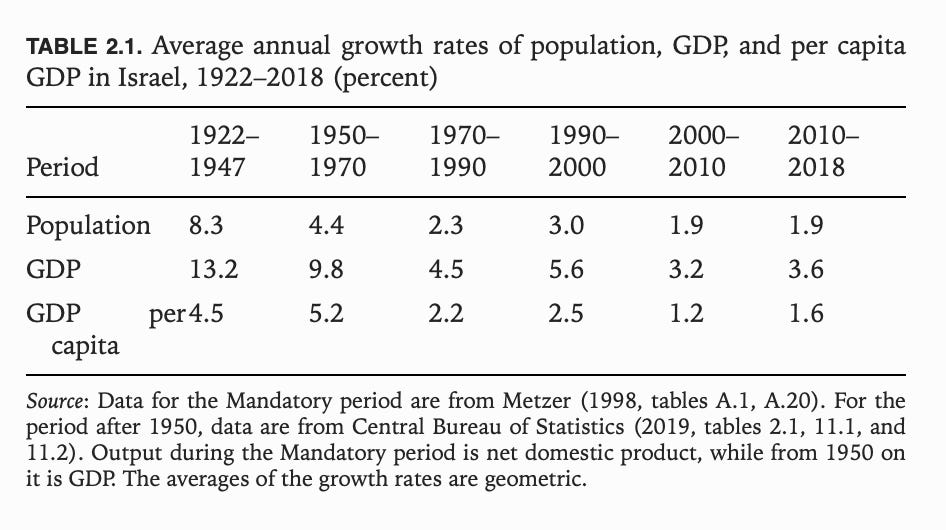

The first phase, now demonized as the phase of Israeli socialism or even “communism”, is the phase which actually established the state and delivered its period of most rapid growth, by far. Israel’s growth in the 1950s and 1960s was amongst the most rapid in the world and that means it was spectacular. Indeed, for context, even the period of crisis-ridden transition in the 1970s and 1990s had higher growth rates than those which are so enthusiastically celebrated today.

Source: Zeira 2021

In making long-run comparisons it is obviously true that Israelis on average today enjoy a vastly higher standard of living than they did fifty years ago. But levels are not the same as growth rates. As elsewhere, in Israel too, the neoliberal era has been one of relatively disappointing growth. At the very least, if market economics was not actually bad for economic growth it was not positive enough in its effects to offset structural forces of retardation.

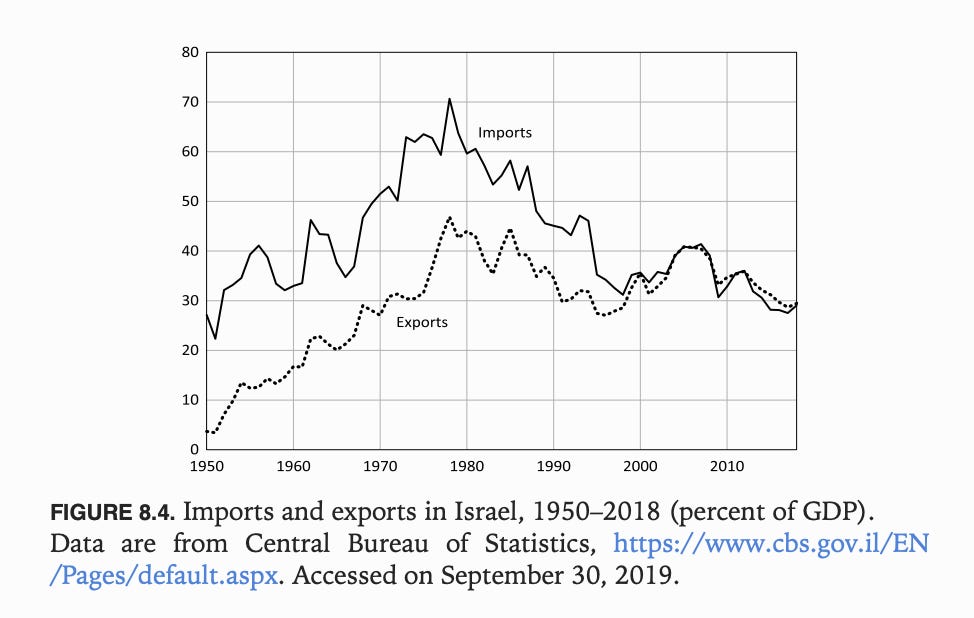

Again contrary to the familiar narrative, a striking feature of Israel’s early decades was the country’s openness to economic flows of all kinds. As it expelled the Palestinian population, it absorbed a huge influx of Jewish migrants. The expanding settler colonial society sucked in foreign goods and it financed the resulting trade deficit by foreign funding, starting with reparations paid by West Germany. Israel today - in the much-vaunted age of globalization - is, in proportional terms, less open to the world economy than it was in the 1960s, above all because its imports were then much larger as a share of GDP.

Source: Zeira 2021

The imported goods and labour was put to good use. Under the social democratic model, anchored in the Labour party, kibbutz, organized labour movement and state-owned industry, Israel experienced dramatic agricultural and urban development. In addition, one of the defining feature of Israel’s political economy in its first decades was equality. By the 1970s, Israel had one of the lowest Gini coefficients in the world. The share of income going to the top 1 percent was as low as that in Sweden. Today it is almost as high as in the United States.

Source: The Privatization of Israel, 314.

In the 1950s and 1960s labour productivity soared. In the socialist period Israel was truly catching up with the United States. Since the 1980s it has been merely tracking the leading economy of the capitalist West.

***

Growth at the rate of the 1950s and 1960s was not destined to last - not in Israel any more than in any other of the growth miracles that followed World War II. Everywhere, the transition from super fast “catch-up” growth to slower growth from the 1970s onwards was painful. In every case it involved a complex transition of growth strategies within the elites, often with social democrats (e.g. UK Labour) or centrists (Democrats in the USA) paving the way for the neoliberal transition that began in earnest the 1980s. Israel followed this pattern in dramatic form, with a period of stagflation culminating with a hyperinflationary burst and abrupt stabilization in 1985.

But to treat Israel as just another case of a runaway corporatism that needed a rebalancing of capital and labour and strong leadership by a central banker - in Israel’s case the legendary Stanley Fischer - is to miss the woods for the trees. The shock of 1973 did not just happen to Israel. The oil shock was unleashed by the climax of four Arab-Israeli wars, a struggle in which Israel was fighting for its survival. That existential struggle shaped all the parameters of economic policy and the pressure did not start in 1973. As in so many other respects it was the 1967 war that was decisive.

Given the scale of Israel’s victory in 1967, it was clear that the Arab world would react and that Israel must prepare to defend its huge territorial gains. Israel was built on war - in 1948 and 1956. But from 1967 onwards military spending surged to unprecedented levels and after the shock of 1973 it continued at extraordinarily high levels. At its peak defense spending amounted to 30 percent of GDP with half of that coming in the form of defense imports. With that kind of burden, macroeconomic imbalance is more or less inevitable.

Source: Zeira 2021

The 1979 peace agreement with Egypt may not have brought peace to the Middle East in comprehensive sense. It left the fate of the Palestinian people undecided. But as Zeira points out in his excellent survey, The Israeli Economy, there is a world of difference between maintaining an occupation regime over a lightly armed civilian population, however brutal, and fighting all-out war of national survival. The peace deal with Egypt turned Israel’s security problem from an impossible burden to a manageable economic and fiscal problem. It was this security settlement that gave monetary stabilization and central bank leadership a chance. The story is brilliantly told in Krampf’s The Israeli Path to Neoliberalism (2018).

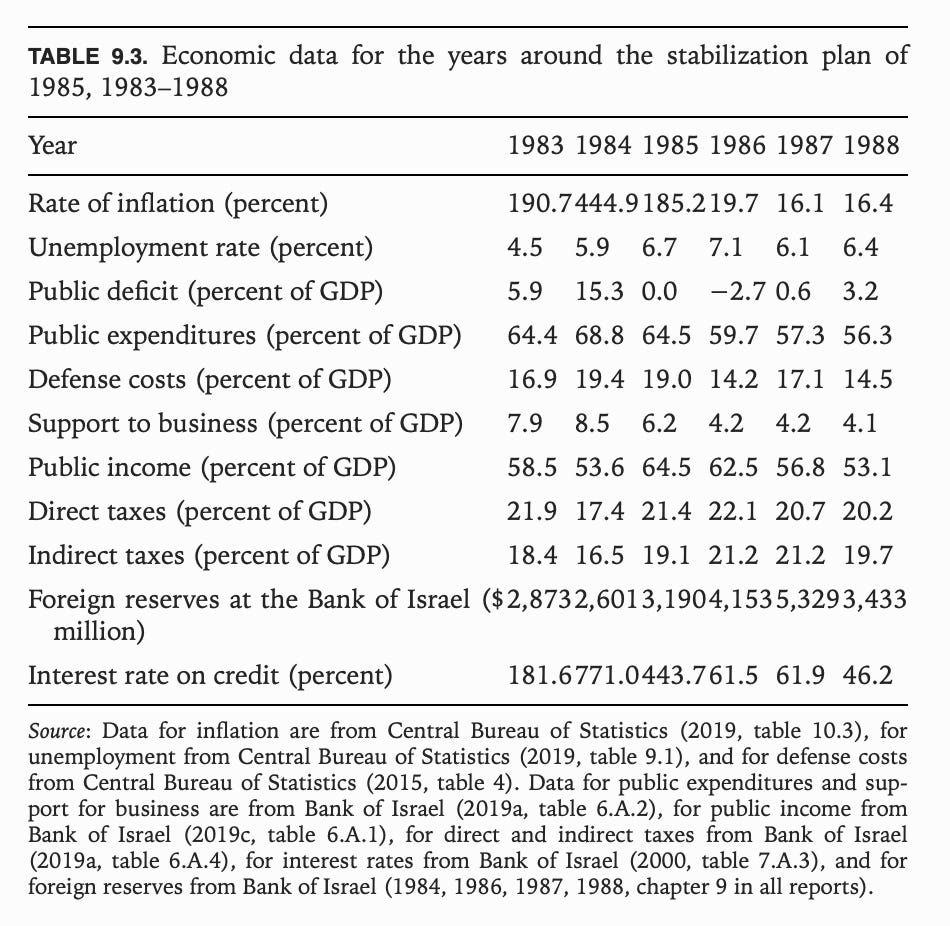

Israel’s economic and financial crisis in the early 1980s was dramatic in its impact. The banking system failed and had to be bailed out. In 1985 Israel had no option but to throw itself on the mercy of the United States to help soften the blow of stabilization. The shock to the government budget and the social and economic model it supported was severe and felt in higher taxation, slashed subsidies and eventually also in much reduced military spending.

Source: Zeira 2021

***

From the mid 1980s onwards, the Labour party - above all through the leadership of Shimon Peres - embraced a threefold policy of domestic transformation, peacemaking and privatized globalization. The degree of Israel’s openness actually declined as it moved away from massive dependence on foreign aid, but in the new era of globalization was that it was private trade and finance not government transfers that dominated Israel’s balance of payments.

In the 1990s the efforts to conclude peace not only with Egypt but to find a resolution of the Palestinian question, went hand in hand with a vision of Israel as the leader of wider Middle Eastern development. A two-state solution, for which a roadmap was established at Oslo (1993), combined with the economic accords of Paris (1994), would open the path to a broader Middle East economic integration, pacification and prosperity. Peres conceived this explicitly on the model of European integration. In 1993, as Europe was set fair to incorporate much of the former Soviet sphere, Peres wrote:

“Ultimately, the Middle East will unite in a common market—after we achieve peace. And the very existence of this common market will foster vital interests in maintaining the peace over the long term” (Peres, 1993, p. 99) (cited in Krampf, The Israeli Path, 219)

As in Europe the precondition for this pacification and stabilization by way of economic integration was US hegemony. What mattered for Israel by the 1990s was no longer simply US government aid, but global capital flows superintended by the United States as the hegemon.

With the Gulf War of 1990-1991, the United States had entered the Middle East more decisively than ever before. The oil industry was globalizing, diluting OPEC’s power. This was the moment that the new vision of a globalized Israel, epitomized by Tel-Aviv’s combination of Bauhaus and Silicon Valley, took off. During his first stint as Prime Minister in the 1990s Netanyahu boasted that Israel was on its way to becoming a

‘high-technology “tiger”’. Israel, in his view, was ‘the Silicon Valley of the Eastern Hemisphere’ and ‘one of the great technological and entrepreneurial successes in the world’. Although the panacea didn’t prevent him from losing the elections, his Labour successor, Barak, was equally enthusiastic. Israel, he declared, was evidently ‘different from any other place in the world’, a country of ‘enormous vitality stemming from the richest possible genetic pool’, which helped it become ‘the most powerful of all states lying in a 1,500 km radius from Jerusalem’.

The growth of the new high-tech economy was accompanied by privatization and deregulation. But to think of this as a “triumph of capitalism”, or victory “of the market over the state” is naive. As Bichler and Nitzan show in gloriously seedy detail, Israel’s high-tech sector was anything but a model of “free competition”. The breakthrough of “private business” relied on state-brokered deals between satellite and cable TV groupings that operated in a highly oligopolistic fashion. Israel’s high-tech start-ups, like their American counterparts, benefited in no small degree from spin-offs from the military-industrial complex.

Meanwhile, the single biggest driver of growth was not deregulation or privatization but the ongoing accumulation of human capital. The labour pool was not just a matter of genetics. It was provided with skills by Israel’s high-functioning public education system and the extraordinary endowment of education brought with them by migrants from the former Soviet Union - socialism twice over you might say. And where the labour pool was not attractive enough, the Israeli government was more than willing to help. Overall the level of public subsidy for business decreased in the course of budget cuts after 1985, but for privileged players like chipmaker Intel, Israel rolled out the red carpet.

As the data show, the optimism of the 1990s was more than just hype. Growth recovered to half the rate of the socialist 1950s and 1960s, impressive enough by global standards. But it did not last. The tech sector was hit hard by the bursting of America’s dot.com bubble. Meanwhile, the optimistic vision of globalization was short-lived. Elsewhere this was a matter of growing inequality and the China shock. And Israel experienced that on a dramatic scale. Inequality surged more rapidly than practically anywhere in the world. By 2011 this would trigger mass protests against excessive housing costs and mounting disparities in living standards.

But in the Middle East, the end of 1990s optimism took a more dramatic and violent turn. Within Israel itself, Rabin’s assassination and Netanyahu’s ascent to leadership signaled the rejection of the Two-State model. The collapse of the Palestinian peace process triggered the outbreak of the second Intifada in 2000. And then the wider regional frame was blown to pieces by 9/11 and America’s War on Terror.

***

Since the early 2000s Israel’s elite has been managing profound tension between its economic strategy of globalization and the destabilized security environment. The synthesis of the 1990s, in which peace and globalization went hand in hand, was gone for good. But there was also no way back to the militarized national economy of the founding era. The retreat of the military from the dominant position in Israel’s political economy has proven permanent. The current mood of anxiety around the “people’s army” are indicative of the questions being asked about the viability of the mass conscription model.

There is no doubt a settler colonial logic at work in the exploitation of the occupied territories. The settlements themselves now account for 10 percent of the Jewish population thus constituting a significant slice of the economy, which in sheer size is on a par with the celebrated high-tech sector. Meanwhile the brutal experiments in counter-insurgency and surveillance offer new opportunities for military-industrial growth in privatized security and in the technologies of repression. To add to the. bitter irony, the system is fed with outside flows of funding for the Palestinian Authority.

These are logics that are compelling at a micro level, for particular actors. But at the broader, strategic level they do not add up. The collapse of the 1990s two-state vision left Israel with a contradiction between its world economic integration and its unresolved domestic security situation. As astute observers like Assaf Adiv noted already in 2007: “(Israel) is torn, in other words, between the refugee camps of Nablus and the cafés of Tel Aviv. With no leadership to resolve these oppositions and close social gaps, Israel today is just plain stuck.”

The contradiction between the notionally liberal values of globalized business and the realities of life in Israel has been plainly apparent for decades. Though this tension cannot be resolved it can be managed by a strategy in which, as Krampf argues, Netanyahu has been a pivotal figure and Israel’s high-tech businesses have been willing helpers.

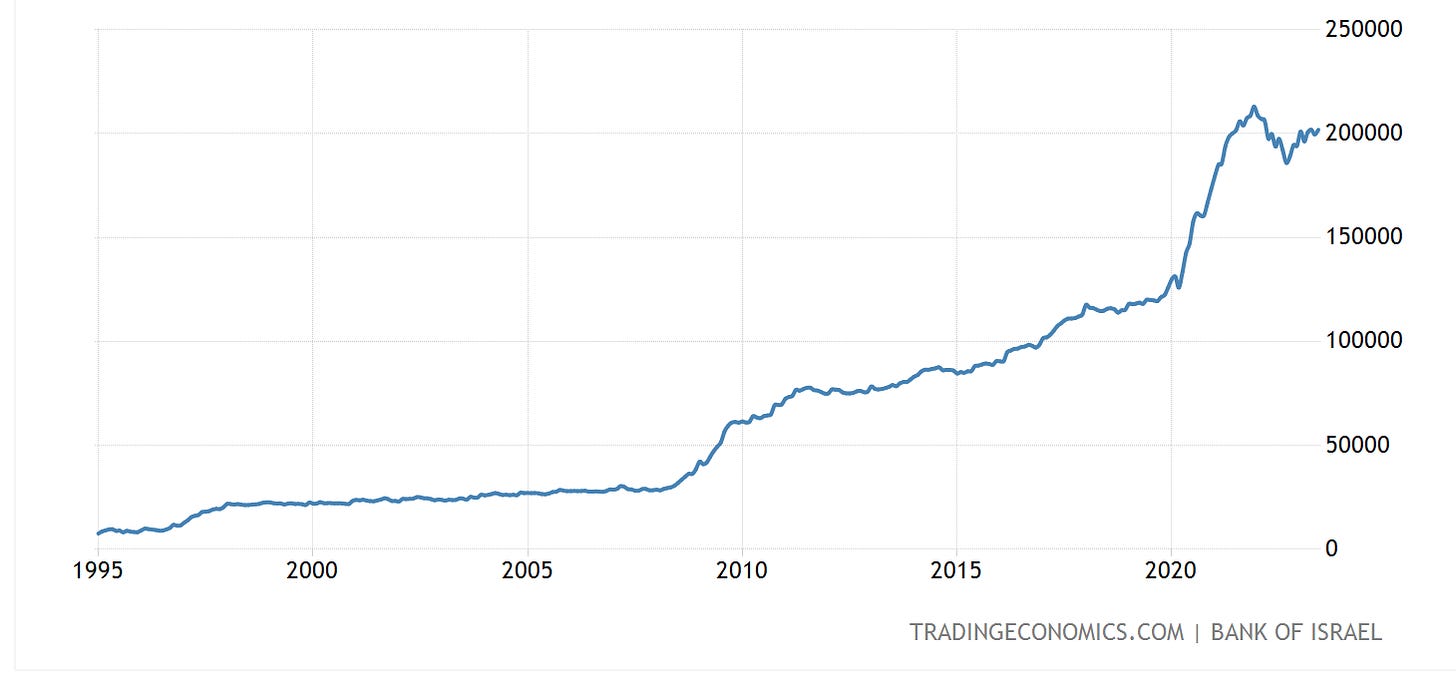

If Israel’s right-wing from the late 1990s onwards saw no realistic prospect of a true Two-State solution, then they needed to be prepared to uphold an apartheid regime if necessary against outside pressure. That would require Israel to secure its independence from its friends as well as its enemies. That meant putting a premium on reducing Israel’s current account deficit and enhancing its resilience in the face of outside shocks. From a country of chronic trade deficits, dependent on external funding, Israel from the mid 1990s onwards turned itself into a country of current account surplus, whilst progressively accumulated an ever larger war chest of foreign reserves.

Israel’s FX reserves in $ millions.

To reiterate the point made earlier, Israel has achieved this turn around in its current account not through a dramatic surge in exports. Today, exports as a share of GDP are lower than at their peaks in the early 2000s or the 1980s. The balance has been closed because imports have fallen, in line with the relative reduction in external assistance and other inter-governmental funding. But the net effect is that Israel’s foreign exchange reserves have surged underpinning a strategy of “self-insurance” not entirely dissimilar to that of Russia or China. Assuming that US sanctions against Israel are not on the cards (the shock Russia has experienced and the scenario that must worry Beijing), a reserve of $200 billion means that Israel can be relaxed about the future of US aid, which currently stands at $ 3 billion per annum. This is the core of what Krampf calls Israel’s calculus of “hawkish neoliberalism”.

***

At the same time as macroeconomic policy has been reinterpreted in national security terms, Netanyahu’s approach to the problem of the occupied territories has been to look not for a political settlement, but for what he calls an “economic peace”.

The idea is that if the Palestinian authority can offer its people better material circumstances, then this will defuse the conflict. As Tariq Dana shows in a fascinating study, this approach was met on the Palestinian side between 2006 and the 2010s by the economic vision of PA Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. It received enthusiastic backing from the Americans and Europeans, notably in the form of US Secretary of State John Kerry’s $4 billion economic plan to boost the Palestinian economy launched at the World Economic Forum in Jordan May 2013. On the side of the Palestinian authority this involved a series of measures to promote private economic development that were loudly applauded by the World Bank. Meanwhile, radical opposition in the refugee camps, notably Jenin, was repressed. And the PA worked with Israel both to establish Export Processing Zones (enclaves within enclaves in the occupied territories) and to promote Palestinian employment in Israel.

As Habbas points out, it is an approach that willfully refuses the inherently political nature of the conflict and the impossibility of actually achieving substantial economic development in the face of disenfranchisement and uncertainty.

These tensions would have been hard enough to manage if Israel had carried through on its commitment to reduce settlements, or even just preserved the status quo of the 1990s. But, instead, Israel’s governments have not just permitted but promoted the expansion of settlements.The result is a progressive fragmentation of the Palestinian territories that inflicts poverty and misery on their 4.5 million Palestinian inhabitants (2.7 million in West Bank and 1.8 million in Gaza). According to UN estimates presented in the spring of 2023, the economic losses inflicted on the Occupied Territories through Israeli restrictions and blockades alone amount to: “25.3 per cent of West Bank gross domestic product (GDP) and the cumulative GDP loss in 2000–2020 is estimated at $50 billion ($45 billion in constant 2015 dollars), which is about three times the West Bank GDP and over 2.5 times the Palestinian GDP in 2020.”

The latest iteration of the policy of “economic peace” consists in a program known as “Shrinking the Conflict”. Proposed in 2018 by philosopher Micah Goodman this starts from the premise that Jewish Israelis do not want to face the demographic implications of a One-State solution, or the security implications of a true Two-State solution. Instead, it recommends the management of “the conflict below the threshold of war, while improving the fabric of life for the Palestinian population.” Proposals to end intrusive security monitoring fail in the face of the violence between insurgent Palestinians, Jewish settlers and Israeli security forces. So what “shrinking the conflict” amounts to are intensified efforts to create parallel, apartheid-style transport infrastructure in which Palestinians, settlers and (Jewish) Israeli society interact as little as possible. It is a surreal logistical answer to an unresolved political problem.

***

As Krampf puts it, Israel’s entire economic model and grand strategy has rested for almost a generation on cognitive dissonance:

What I call the Netanyahu doctrine is based on geographic, institutional, and even mental separation between Israel as a globalized economy and Israel as a state that occupies a territory and engages in a territorial conflict.

There are at least four axes of tension and cognitive dissonance at play here

Between Israel and the Palestinians.

Between Israel’s occupation regime and global liberal norms and active solidarity with Palestine.

Between Israel’s growth strategy and the social balance of Israeli society, as measured in inequality and sensitive indicators and housing costs.

Finally, there are the ideological and cultural differences within the Jewish population of Israel which Netanyahu’s coalition have forced into the open and intersect with global culture wars along lines familiar from the United States, Brazil, Russia, India and Australia.

Under the impression of the 2011 social protests, Krampf speculates that the third axis of tension is the greatest blindspot of Israel’s geoeconomic strategy. It will be undercut by the social tensions it unleashes.

The media coverage being given to the Angst of some liberal Israeli entrepreneurs in the face of the current illiberal turn no doubt reflects real worries in Tel Aviv. But in truth Israel’s political economy has existed in profound tension since the collapse of the peace process in the late 1990s. As far as Netanyahu and his coalition are concerned the constitutional changes they are promoting will actually make those tensions easier to manage, by preventing interference by liberal hangovers in the judiciary.

The bigger question surely is how far the right-wing course pursued by Israel alienates not just tech entrepreneurs but potential partners in the Abraham Accords. The accords seemed to offer Israel the chance of restarting the 1990s vision of a regional growth club, without having to resolve the Palestinian question. A wider economic peace - in Netanyahu’s terms. But as tempting as it may be for Israeli and other strategists to think in those terms, you cant go back to the 1990s. The Occupied Territories are an open wound and the world Israel is navigating today is far more multipolar than that in the 1990s. One aspect of that is the emergence of China as a key player. But another aspect is the heft of Israel’s putative partners in the Middle East. Israel’s is not the only economy in the region to have gone through a developmental spurt in recent decades. Turkey’s economy is almost twice the size of Israel. Saudi Arabia’s is more than three times larger than Israels. Even the economy of the UAE today plays in the same league as Israel.

And if Israel has made itself relatively proof against pressure from Washington, so too have its neighbors. They pursue independent regional foreign policies and entertain relations with both China and Russia, which are far from pleasing to Washington. This offers new opportunities for Israel’s strategists. But also, as the Chinese brokered rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Iran suggests, new risks. If the last 75 years are anything to go by, it is less the question of Israel’s liberalism that will be decisive, than the way it navigates this forcefield.

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.

Far right means supremacy to the will of the people as opposed to deference to authoritarian elites?

Man...

This is a Marxist text..

Is quite obvious that the very first years would realize huge GDP growth

The question is if during the after decades, in wich slowed the immigration waves, the mean through Israeli society started to self-organize - the kibbutz - would remain feasible

As we know looking from ex post perspective, an entire society couldn't survive by kibbutz model.

Socialism cost is too much expensive