Chartbook 227 Team transitory or team soft-landing? "Bounding reality" in the 2021-2023 inflation debate.

In the US inflation debate that has been on-going since 2021, there were three broad positions: hard landing, soft landing and team transitory. In light of the most recent numbers, with both inflation and unemployment in the three percent band, only two remain plausible.

The hard-landing scenario centered on alleged policy mistakes. The fiscal stimulus of the early Biden administration in the spring of 2021 was excessive. Monetary policy on the other hand was too slow to respond to the emerging threat of inflation. Hard-landing advocates warned of a serious risk of the disanchoring of expectations. If fiscal policy had been more moderate and more focused. If the Fed had reacted more promptly, the recovery would have been smoother. Now, the Fed’s response was going to have to be more severe than necessary and more painful in its efffects. For this double failure there would be a political price to pay in the midterms and the 2024 election. The Fed and other central banks were called upon to engage in profound self-criticism for their failure to predict the inflationary surge.

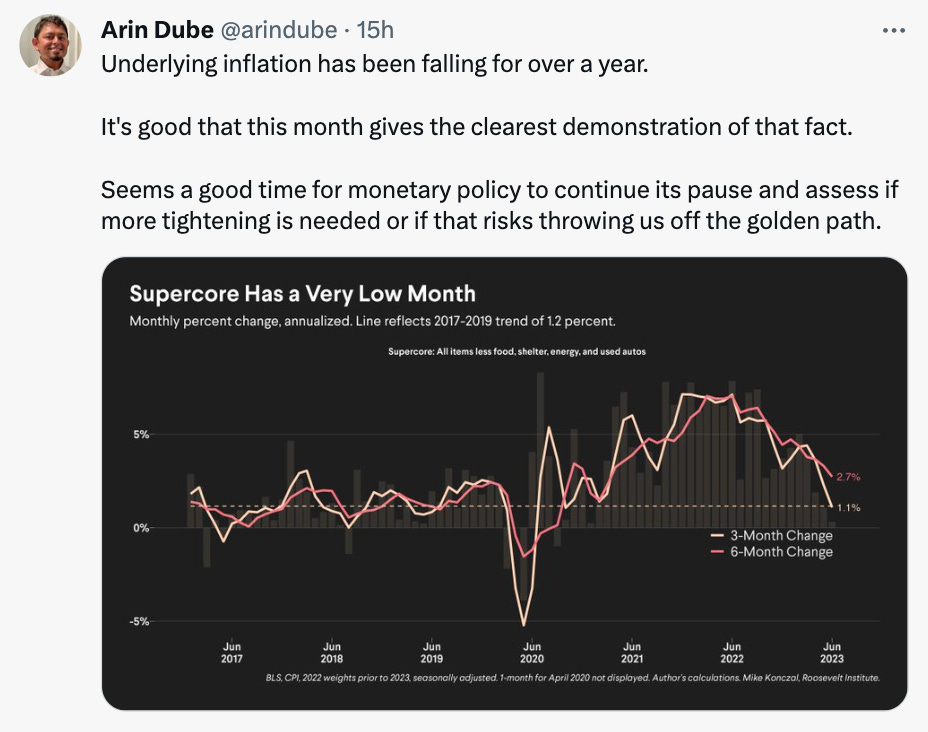

With both inflation and unemployment in the US at 3 percent, this diagnosis now seems alarmist. The main risk would seem to be that the Fed in a misguided effort to get quickly from 3 to 2 percent might tip the US economy off its “golden path” (Goolsbee). This would not so much confirm the hard landing hypothesis as turn it into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If there needs to be a postmortem it is not so much on the policy framework of the Fed but on the vociferousness with which hard-landing advocates made their case and continue to make their case. You might ask what motivated that vociferousness, or what place it has in the structure of economic policy discourse. You might ask what its consequences will turn out to be. I put some of those questions in an FT column. And in various newsletters. Those questions are important but they may be less urgent now in the US than they are in the UK and the Eurozone.

In the US, barring a savage round of final Fed tightening, reality is now bounded, as Arin Dube put it, by the two other options:

One is that we are, in fact, living the sanguine scenario of the soft landing.

Like the hard landing scenario, this is a primarily policy-centric view.

It starts from the premise that in 2021 US policy-makers were right to be in emergency mode. The US was exiting from a profound political crisis. After the chaos of Trump’s last year in office, it was crucial for the Democratic Party leadership to demonstrate their capacity to respond to the pandemic, America’s looming social crisis and the high levels of unemployment. Of course, there were risks, as identified by the likes of Summers and Blanchard. But their alarmism was itself mistimed. It came as the Biden administration was struggling to steady the ship. And if the worst came to the worst, there were ways for policy to address inflation.

If inflation did break out, the Fed could do its job. It would raise rates. In the mean time, weighing unemployment, growth and welfare against inflation, and preferring to keep the taps open, was not a feckless mistake, but a calculated risk. What America needed to worry about in 2021 and 2022 were not the anxieties of the 1970s but the very real threats of the present.

As John Williams of the New York Fed put it to Colby Smith of the FT:

The lesson to me is that when you are dealing with extreme uncertainty and risk management, you are going to have to make decisions based on what you think the worst risks are. Our actions in the spring of 2020 in terms of asset purchases were extraordinary. The speed and the scale at which we did this was just unprecedented. That was not a case of gradualism, that was not a case of caution, it was a case of decisive action. It wasn’t clear in real time how much you needed to do, or how long would you need to do it, but it was clear that we needed to do it. The tail risk in 2020 and into 2021 was an economy that didn’t recover. Obviously, at the end of the day, it did and that’s great, though the cost of that was that inflation took off faster and much higher than most people expected and we needed to shift gears. That was the risk that we had to face.

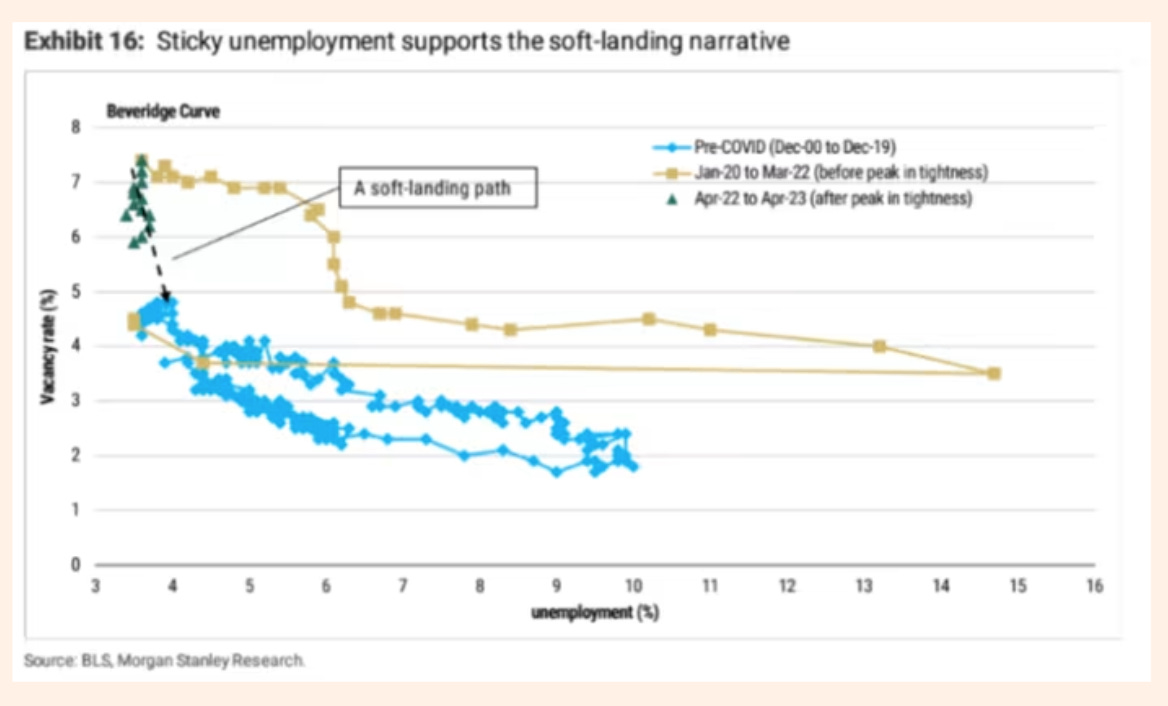

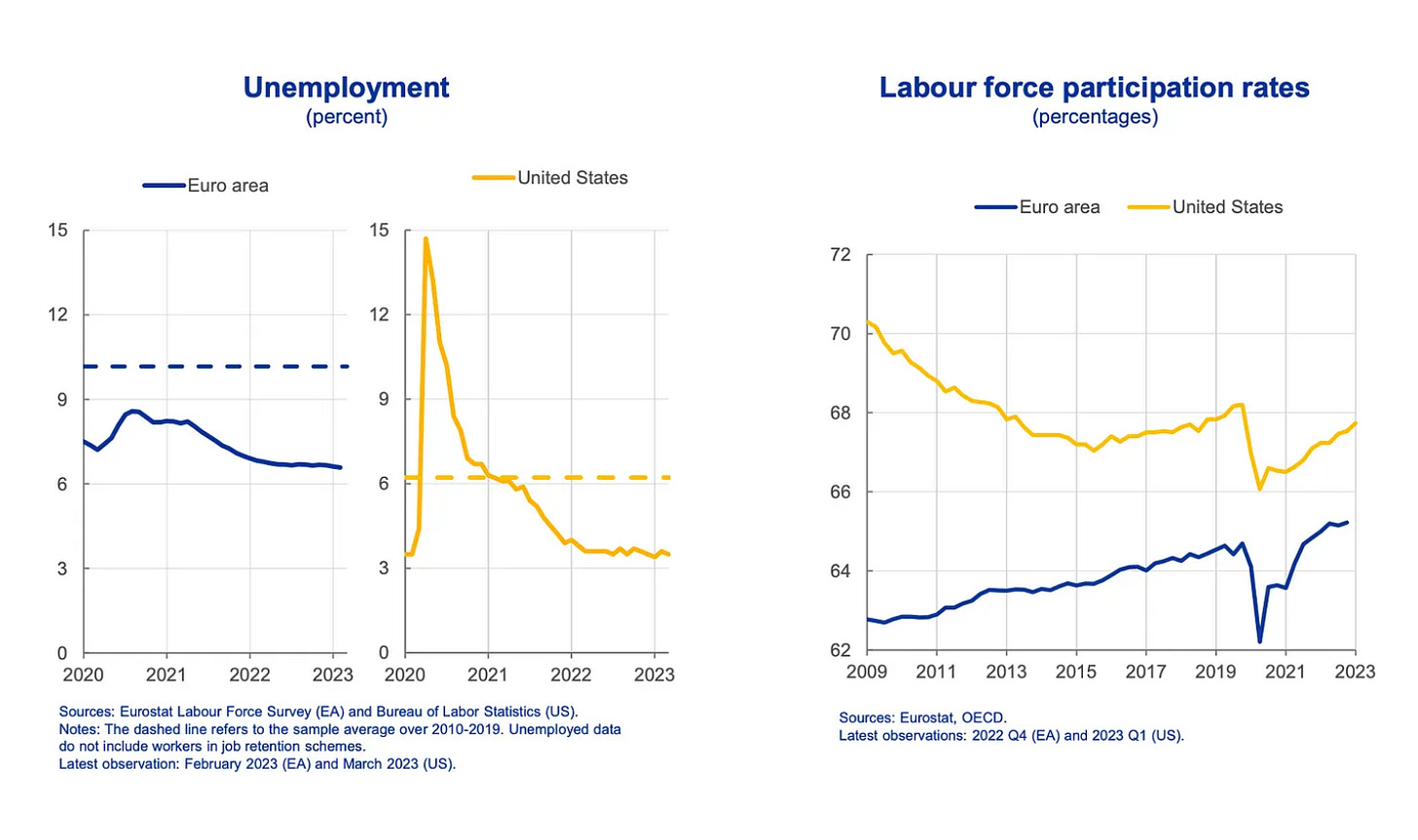

As it turned out, inflation went higher than many folks expected. But, as interest rates went up since early 2023 inflation has been coming down. And, as it turns out, this has happened without unemployment having to rise very far. This vindicates those like Christopher Waller who believed that unprecedented things might happen on the Beveridge curve.

No hard landing! Far from it. Policy has not suffered a double failure (excess fiscal and belated monetary). On the contrary. It has done its job in a historically remarkable way. Fiscal policy was dramatically, but appropriately expansive when it needed to be. Then monetary policy tightened sharply and brought inflation down at relatively low cost. If we have the courage to use them, our instruments work.

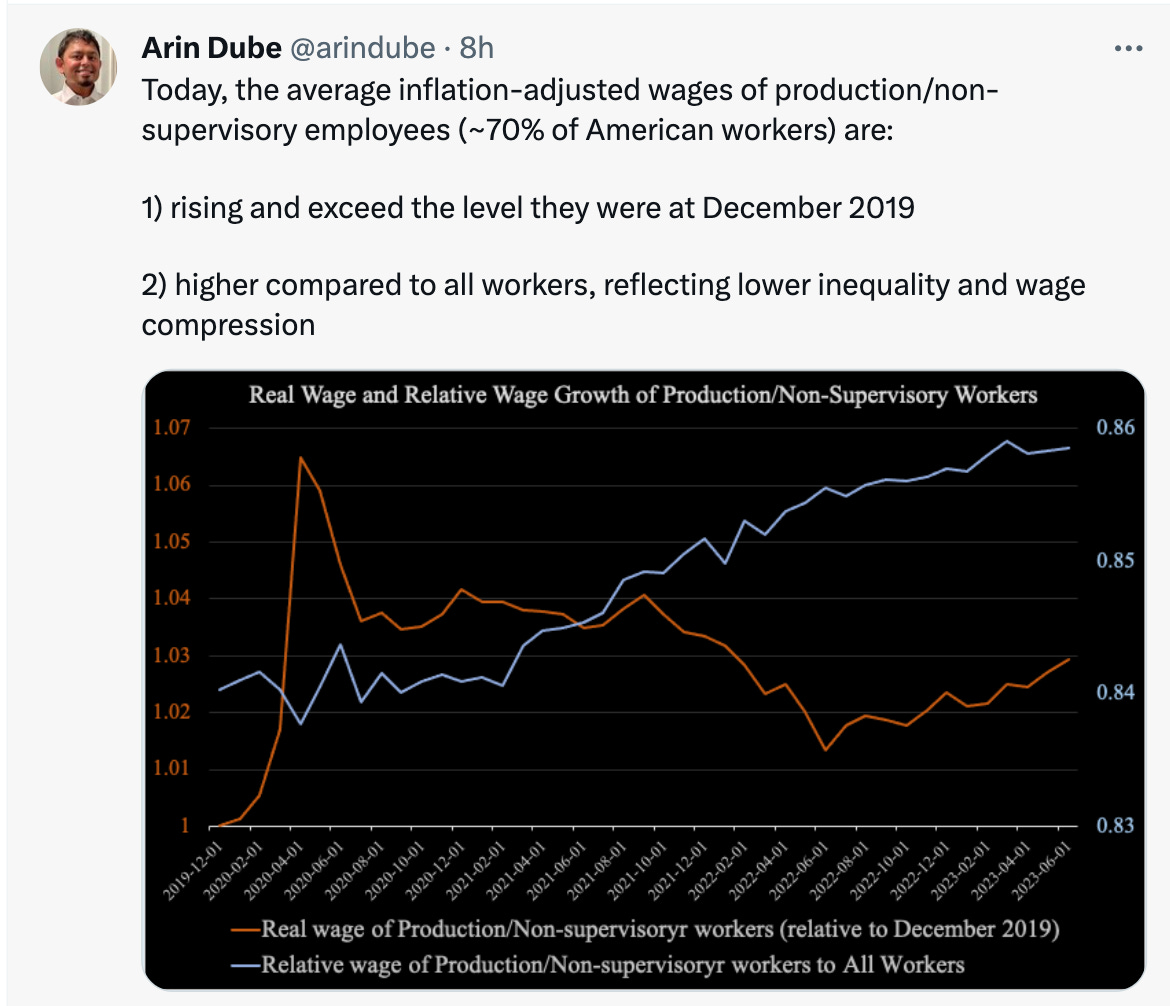

This is not to discount the costs of the inflationary surge itself. Real wages were exposed to gyrations along the way. But, as Dube points out, for the vast majority of American workers, real wages are now above their December 2019 levels and rather than exacerbating labour market inequality, the combination of policies adopted since the onset of the COVID crisis has produced, intentionally or unintentionally, a substantial compression of wage differentials.

America survived a major crisis without further exacerbating labour market inequality (at least measured by compensation, as opposed to security of employment). And the Overton window on issues like the racial dimension of unemployment and labour market inequality has shifted dramatically. The US has not seen the union mobilization witnessed in Europe, but organized labour has regaind relevance. These are significant wins.

All in all, as many are now concluding, the post-COVID period is as exceptional an episode in American economic history, as the COVID episode itself. We are not living through a regular business cycle, but a process of abrupt adjustment and readjustment that disrupts conventional relationships. The same can also be said with regard to US politics and the broader debate about economic policy.

And this is reflected in the inflation debate as well. Because alongside the relatively conventional policy-centric hard-landing v. soft-landing camps, a third line of argument has gained real traction. As a short-hand, I will call this team transitory.

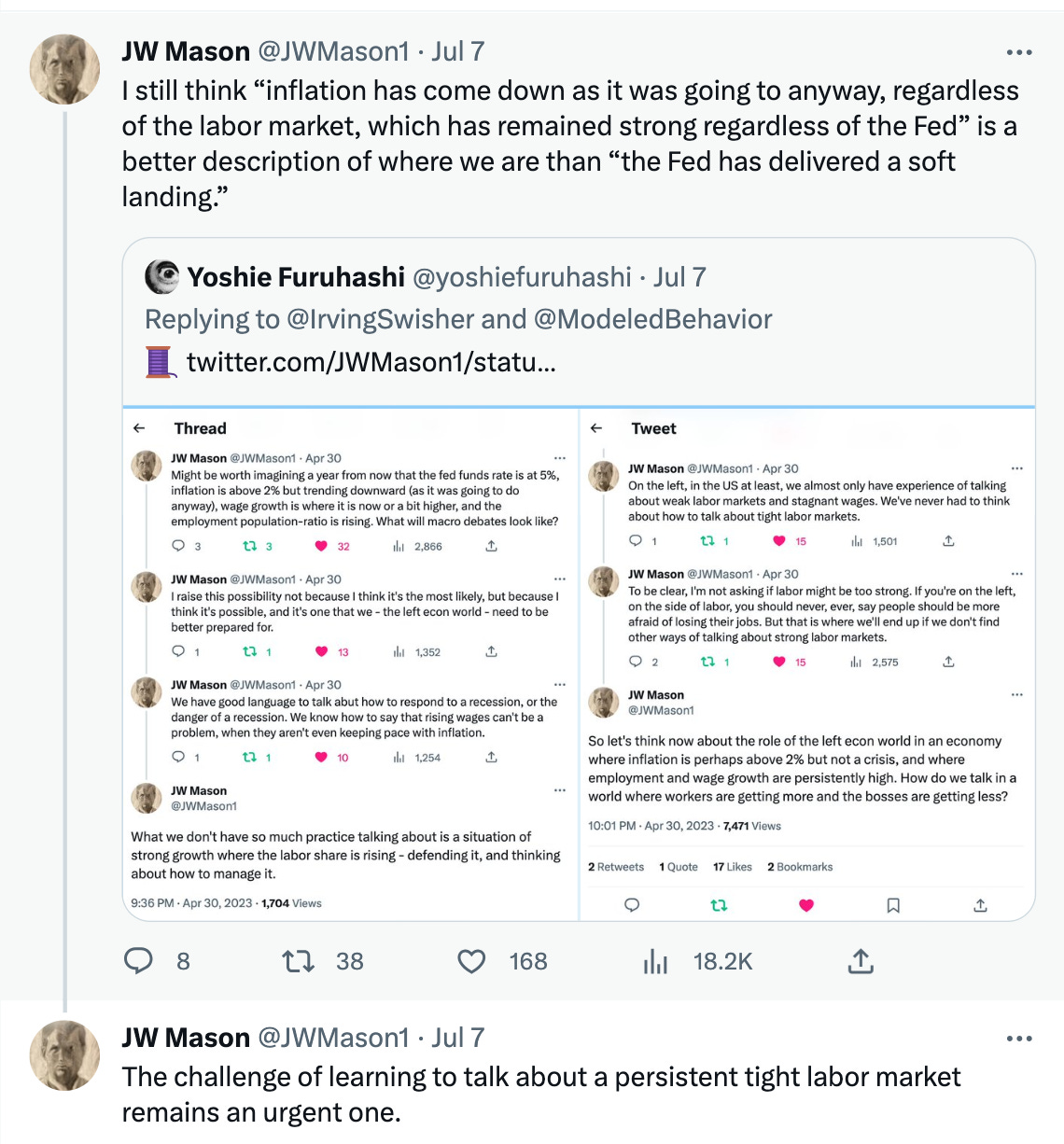

Team transitory is distinguished from team soft-landing above all in the role they attribute to monetary policy in explaining both the upswing and the downdraft of inflation. Team soft-landing centers the Fed in the anti-inflation fight. The basic contention of team transitory is that the Fed is largely irrelevant.

For team transitory the 2021-2023 inflation originated in unusual shocks in particular sectors. It is questionable whether it really qualifies as a general inflation as opposed to a price shock which briefly gained some general traction. The sectoral price shocks disrupted the price system and opened the door to aggressive price setting by some businesses. This unleashed a very uneven process of adjustment in both prices and wages, led mainly from the price side. This was very unhelpfully described as “greedflation”. This is unhelpful because greed is not the issue. The calculus of price setting in imperfect markets is.

Easy credit conditions (monetary policy) and large household and corporate balances (fiscal policy), if they played any role at all, enabled this price adjustment rather than driving it. (One sub camp in team transitory would allow a role for excess balances but this is much debated). There was little evidence for self-sustaining spirals of wages and prices, or any disanchoring of expectations, or any of the other dynamics supposedly reminiscent of the 1970s. And so inflation came down again as it had gone up, without much direct link to labour market conditions, or monetary policy. Energy prices spiked. Supply-chain difficulties unraveled as COVID-restrictions around the world ended.

As J.W. Mason puts it, the Fed can take neither blame nor credit for the process.

If Mason and other advocates of the strong version of transitory hypothesis are right, then the vast majority of conventional policy discourse - along with the mainstream macro that sustains it - is beside the point.

From team transitory’s position, the soft landing view at least accords with the basic facts of the US experience. But it too has questions to answer. If credit is to be given to monetary policy in cooling inflation, how exactly does it work?

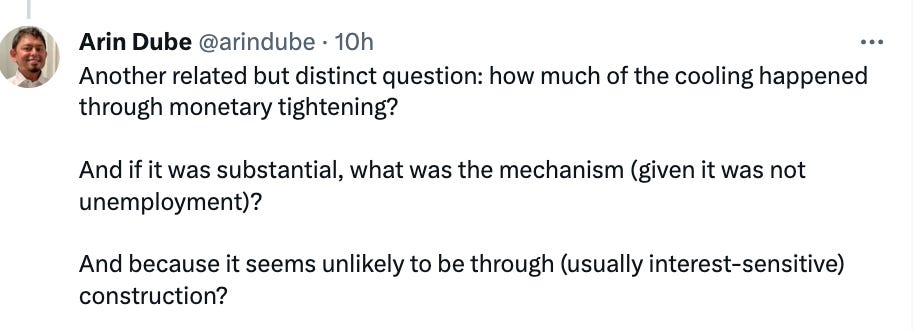

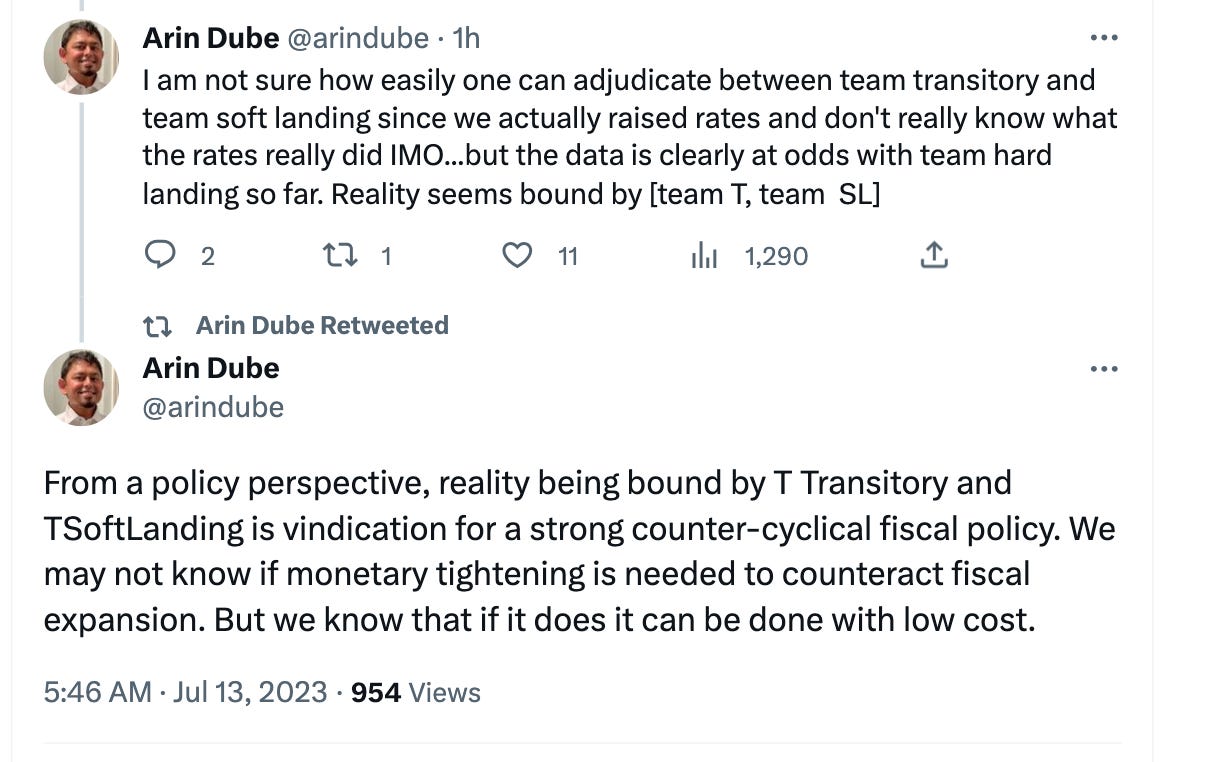

As always in historical interpretation our problem is that we cannot actually run experiments. As Dube puts it:

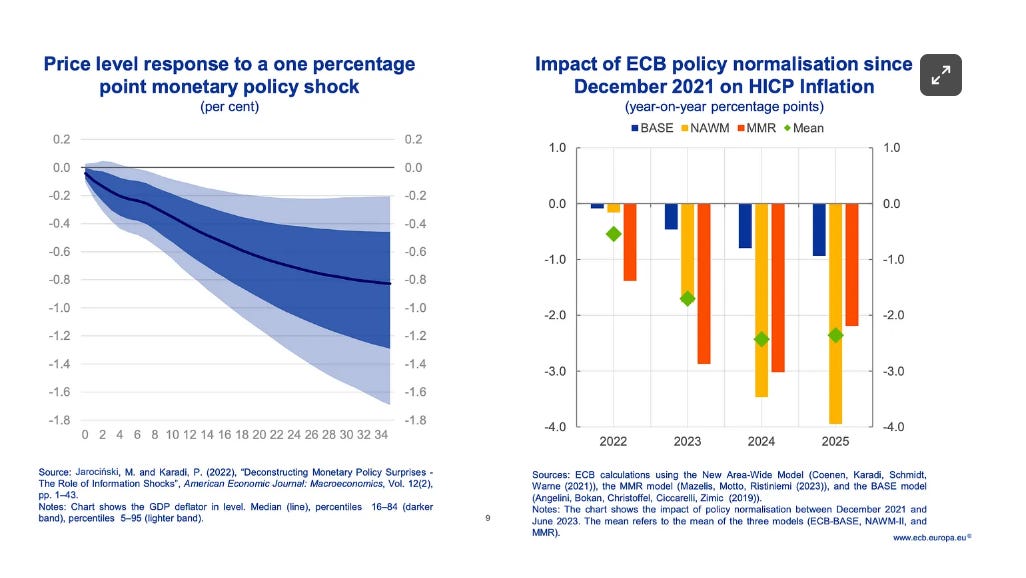

In the second tweet, Dube may go too far. At this point we don’t know enough to say with confidence what effect monetary policy does or does not have. Honest practitioners like Isabel Schnabel of the ECB admit as much. As she showed in a recent talk, the ECB’s models give wildly different predictions as to the impact of any given interest rate hike.

But with the historical import of Dube’s second point one can surely roundly agree. There is no good reason to regret the scale and urgency of fiscal policy action in the US (or Europe) in 2020 and 2021. Both in the US and Europe it has yielded remarkably good labour market outcomes, which should be cause for celebration and not anxiety and alarmism.

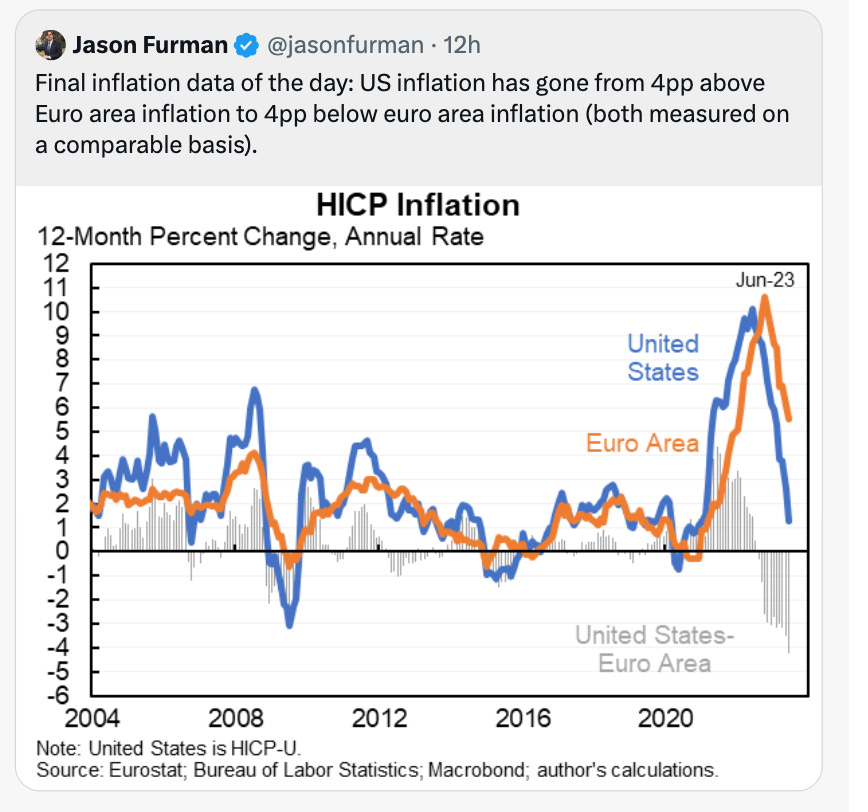

As far as the current inflationary episode is concerned, attention now shifts to Europe and the UK where the headline numbers are still higher than in the US, where collective bargaining is more important and where the politics of “there is no alternative” continues to hold sway.

In the USA, though the inflation scare may be wearing off, what we now squarely face is the political question.

At the political level, the inflation debate in the US, propelled as it was by the alarmist hard-landing view, was both about specific (pessimistic) predictions and about the general question of authority in the handling of economic policy. This issue of “gatekeeping” came to the fore with a vengeance in the bitterness of the debate over “price control”. Whatever one thinks of that debate, whatever one thinks about the soft landing, whatever one thinks about the other flank of Bidenomics i.e. industrial policy and the IRA, the polling numbers are sobering and they pose a seerious question.

By any reasonable standard, with inflation and unemployment both at 3 percent and real wages for most Americans above 2019 levels, inequality down, and both the manufacturing and service sectors coming back strongly, the economic situation is far better than we had any reason to expect both in light of the severity of the 2020 shock and America’s previous track record, for instance after 2008. And yet approval for Biden’s handling of the economy currently stands at 34%, which is even lower than his overall approval rating of 41%, according to the survey from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

What does this tell us about how Americans form their views about the economy and economic policy?

What evidence and which voices, if any, sway them? What is their counterfactual? How do they imagine this could have gone better? Why are they convinced that they are in the middle of a hard landing, when they are in fact experiencing the opposite?

***

Thank you for reading Chartbook Newsletter. It is rewarding to write. I love sending it out for free to readers around the world. But it takes a lot of work. What sustains the effort are voluntary subscriptions from paying supporters. If you are enjoying the newsletter and would like to join the group of supporters click below. As a token of appreciation you will receive the full Top Links emails several times per week.